Eunju

Hong’s practice begins with a view of the history of technological development

as a reflection of human desire. Rather than accepting the dominant narrative

that technology has been invented to improve life, she focuses on how

fragility, violence, loss, and repression have accumulated alongside

technological progress. This perspective leads her to approach technology not

simply as a tool or an object of critique, but as a field in which human

emotion, memory, and embodied experience are deeply entangled. Through her

work, Hong elevates the points of collision between technology and emotion,

matter and memory into states of poetic tension, persistently examining moments

where personal wounds overlap with social ones.

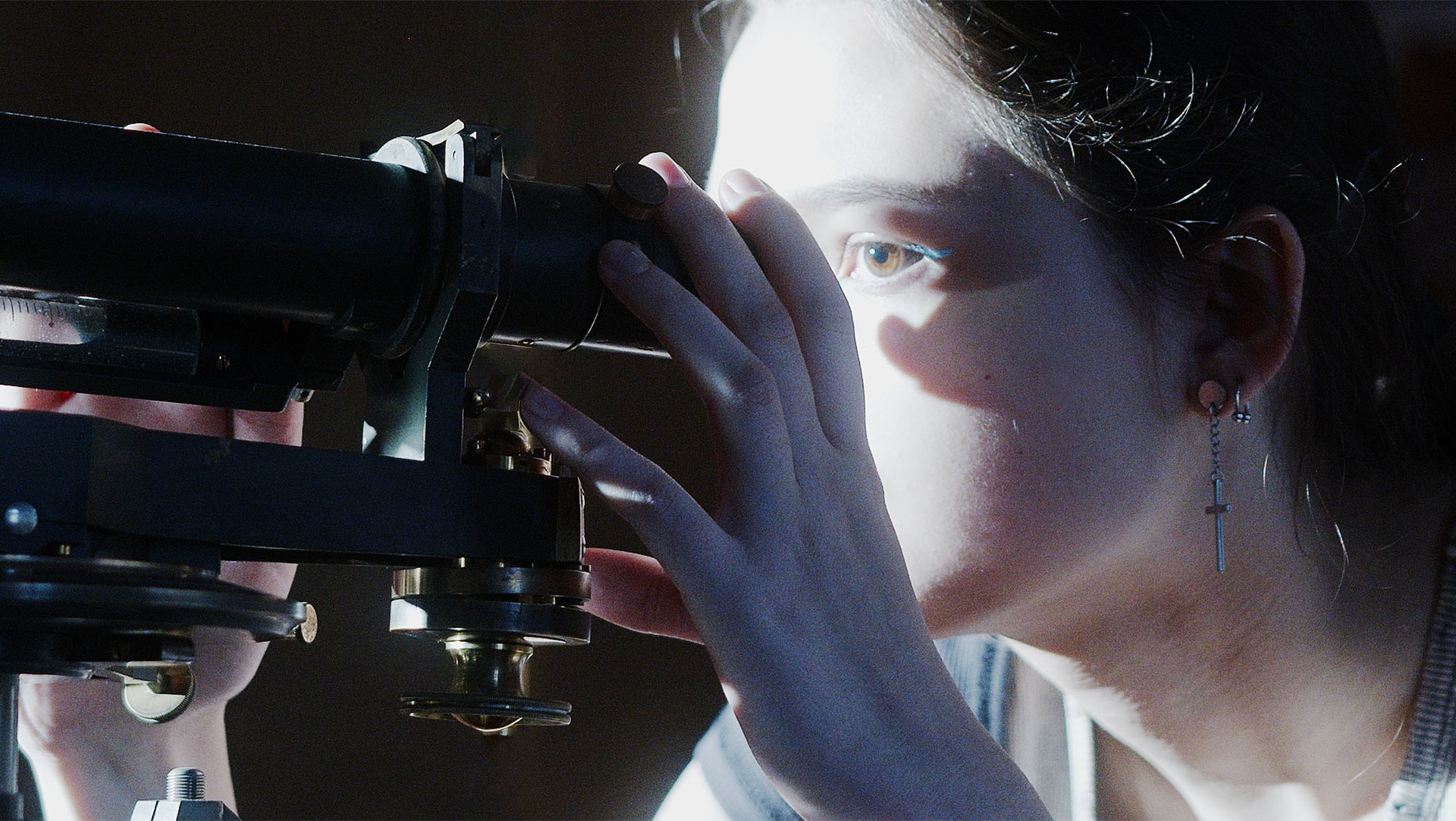

From early

on, her interest has centered on how “the body” and “matter” are transformed

and acquire meaning within technological contexts. High

Fever(2023) reveals the vulnerability of human existence through the

relationship between medical technology and the body, showing how technology

paradoxically functions as a device that makes human incompleteness visible.

This approach shifts attention away from technological outcomes toward the

emotional residues and traumas produced in the process itself.

In her

solo exhibition 《I want to mix

my ashes with yours》(Gallery175, Seoul, 2022), Hong

imagines a situation in which the boundaries between heterogeneous

entities—humans, buildings, machines, and animals—collapse. Here, the concept

of the body is expanded from a singular subject into a non-linear network of intertwined

beings. The phrase “mixing ashes” is recontextualized beyond a metaphor for

eternal love, instead pointing to contemporary conditions in which the

boundaries between forms of existence become increasingly ambiguous.

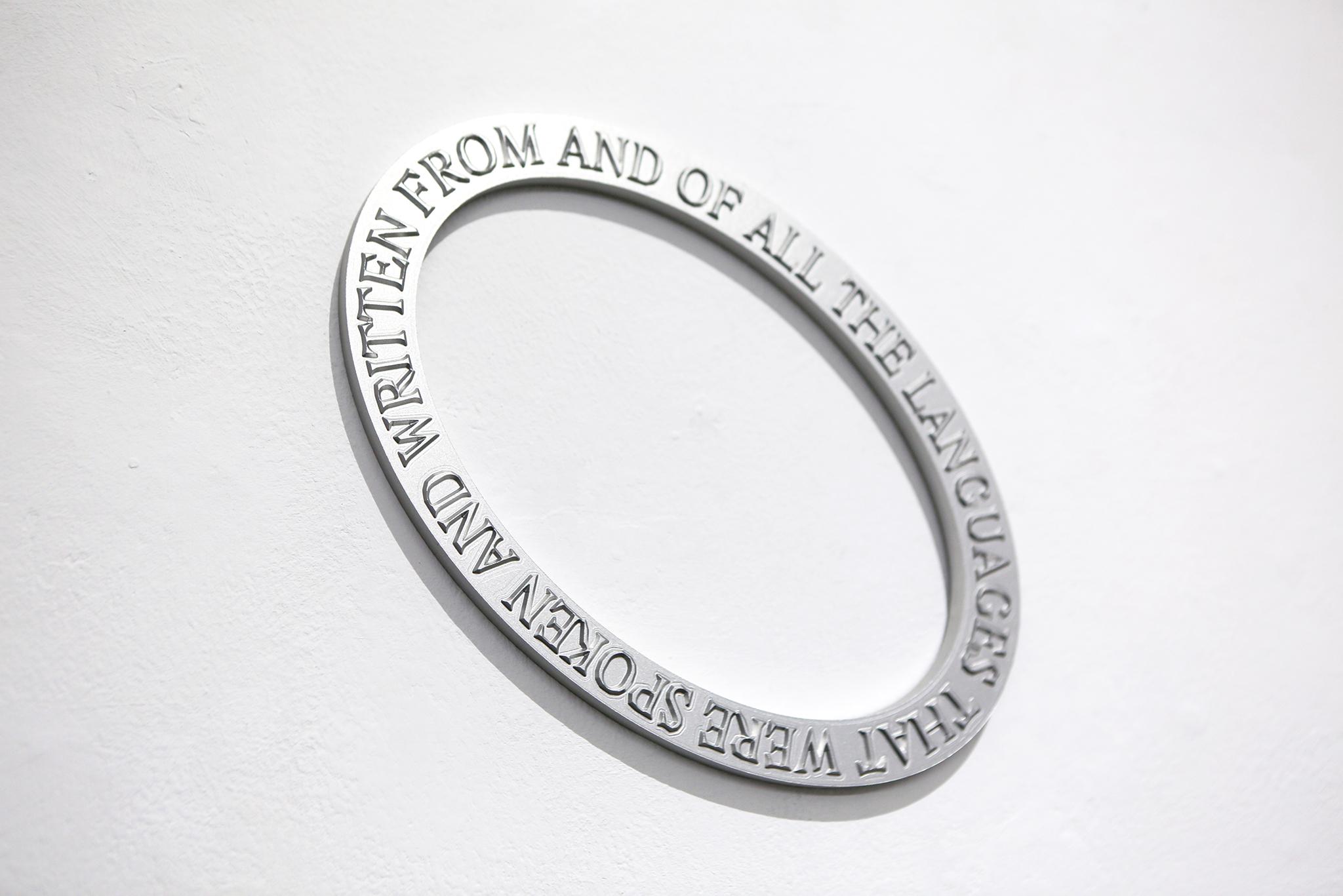

In her

later works, Hong further expands her inquiry into issues of technology, power,

and the gaze through the keywords of wound, suturing, manipulation, and

representation. Suture(2023) and the solo exhibition 《Suture-rewired》(Arcade Seoul, Seoul, 2024)

trace how wounds have historically been transformed into spectacle and

subsequently concealed, beginning with the “operating theater” of Western

medical history.

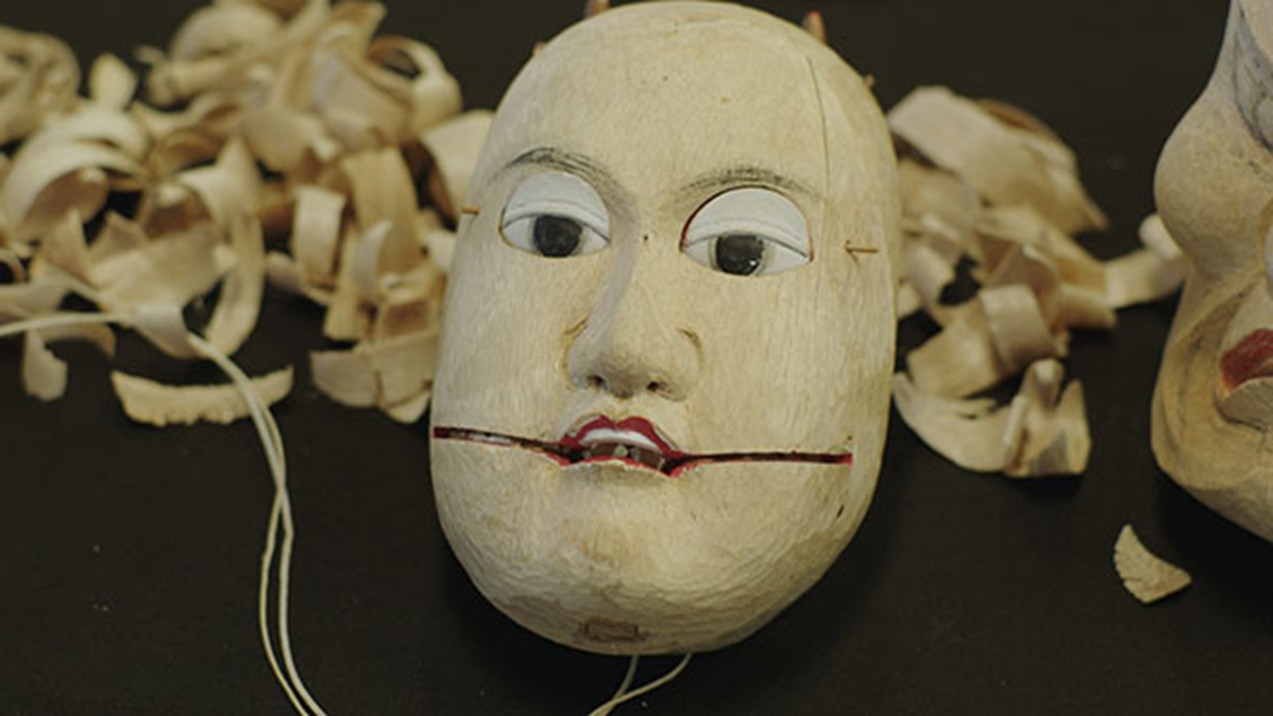

More recent works, including She seemed

devastated, when I was weeping with Joy(2025) and the solo exhibition

《Shadow Play》(Faction, Seoul,

2025), draw on the contexts of puppetry and traditional theater to examine

structures of emotional transmission between humans and nonhumans, performers

and objects, continuing her investigation into the intersections of technology,

the body, and memory.