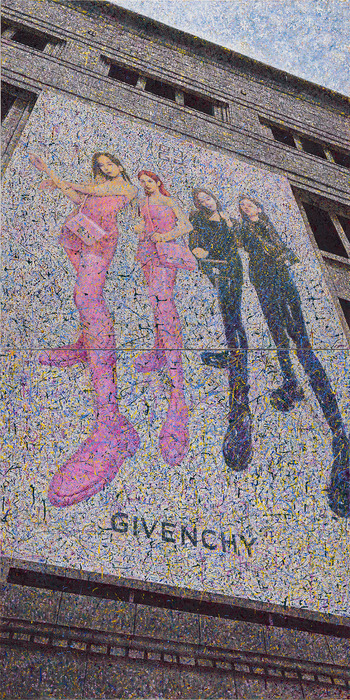

Hyewon

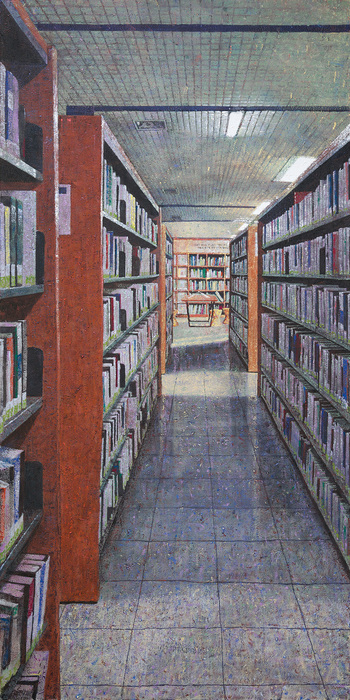

Kim’s practice begins with photographing the everyday landscapes she repeatedly

encounters and translating them into painting. Works such as Ginkgo

Tree Soaring High(2020), Mapo Central Library(2021),

and Inside The Subway Line 2 Train Crossing The Dangsancheolgyo (Rail

Bridge) (2022) originate from her close observations of places she

passes through and from re-examining scenes captured through the photographic

lens. The artist questions how photography flattens the world into a kind of

shallow “relief,” fixing depth, atmosphere, and temporal flow into a uniform

surface. By restoring these omitted layers through painting, she reconfigures

everyday spaces not as simple records but as complex environments shaped by

memory and perception.

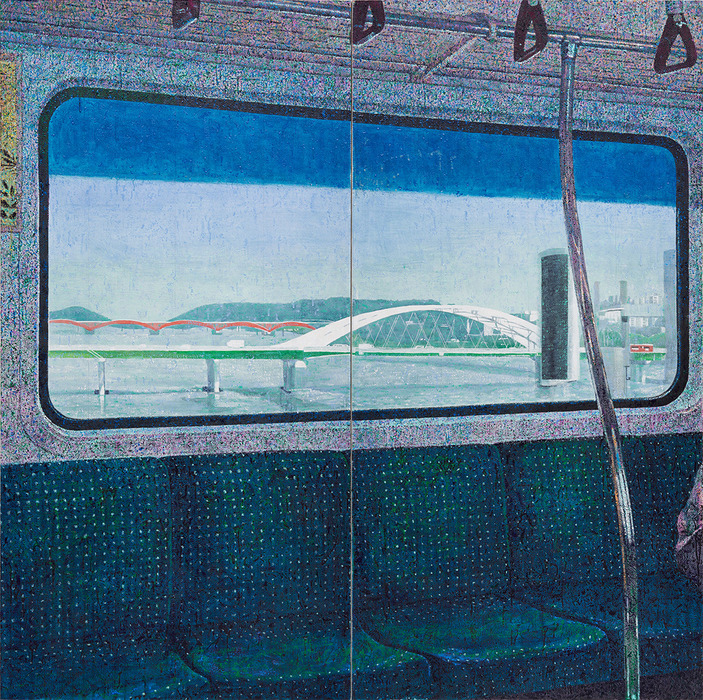

Her

interest lies in reconstructing what exists beyond the visible surface. Kim

recalls residual spaces that photographs cannot contain—backgrounds hidden

behind foreground objects or peripheral details that fall outside the frame—and

reassembles them like a design blueprint to form new sensory landscapes. Rather

than straightforward representation, her work reveals how our perception of

everyday life is constructed and what tends to be overlooked. In her first solo

exhibition, 《Thickness of Pictures》(Hall1, 2022), she depicted familiar spaces such as subway and bus

interiors with the human presence intentionally removed, creating a heightened

spatial tension and a stronger sense of structure within this emptiness.

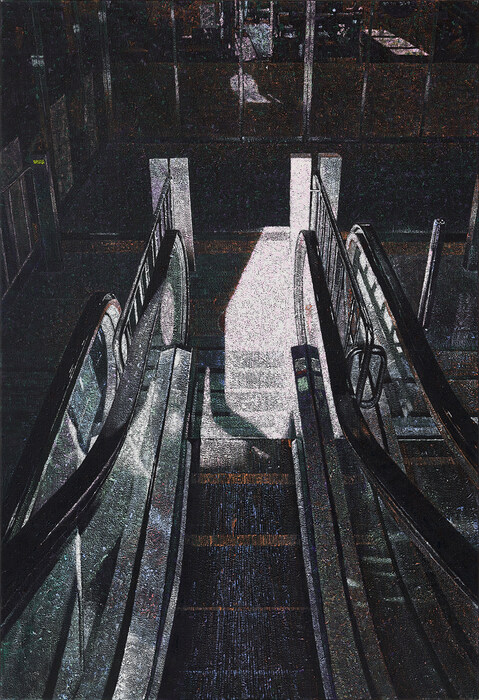

Her

thematic focus later expanded from space to time. In her second solo

exhibition, 《Day and Night》(Space Willing N Dealing, 2023), temporality—shifts in light,

seasonal change, and the daily cycle—became central. Works such as Hongik

University Station Escalator Exit1(2023) highlight subtle “temporal

layers” that photography fails to capture: the color tone of a specific hour,

the direction of light, and the air that fills a space. Her paintings capture

moments in which particles of light and color are perceived before the identity

of the depicted subject, suggesting that the world is composed not of stable

“background–figure” structures but of shifting units of luminosity and hue.

In her

recent solo exhibition 《A Picturesque

Tour》(PCO, 2025), her conceptual direction moves even

further—from everyday observation toward the history of images, the tradition

of landscape painting, and the act of seeing itself. Works such as In

the Forest(2025) and A Cat Under the Car(2025)

invite viewers to reconsider what it means to “look at a landscape” by

employing mediating devices such as smartphone reflections, panoramic

viewpoints, and the historic “black mirror.” By placing contemporary smartphone

vision alongside classical ways of viewing nature, Kim examines how habitual

image consumption can be transformed back into painterly perception.

Ultimately, she explores time, light, and memory embedded within daily scenes,

making the mechanism by which images operate a central conceptual axis of her

work.