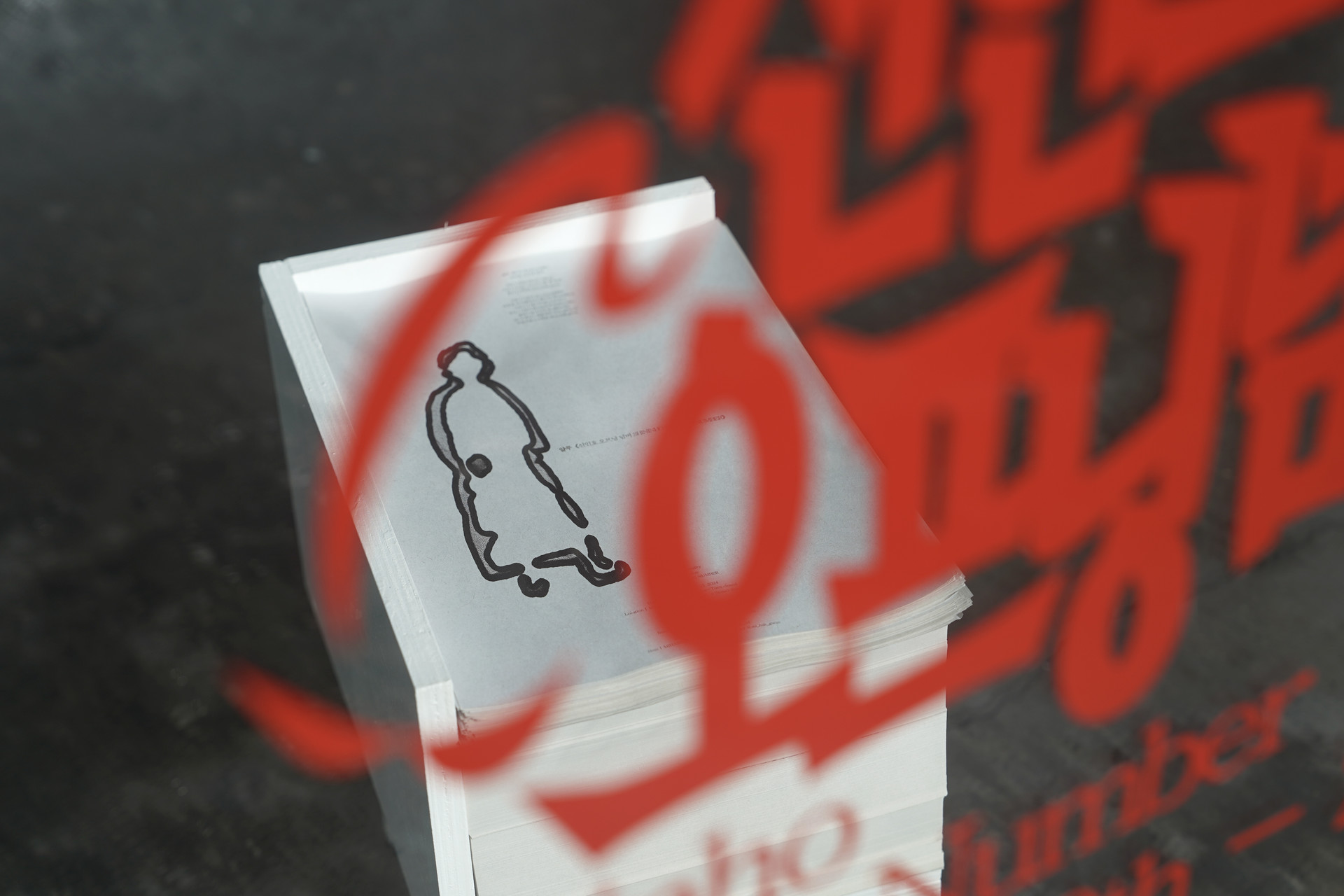

Shininho 申仁浩

Each morning, she places water on a small altar she has set up in the corner of

her room and prays to her ancestors—whose identities she no longer clearly

remembers. She cannot quite recall for whom she prays or what she prays for,

but she asks the heavenly and earthly deities that all things may be at peace,

and that the rest of her life may be tranquil. She prays to finish this life

quietly without relying on anyone or being a burden, without any major

incident—just as things are now.

The glories of youth are long gone. She

straightens her clothes each morning and steps outside, but with nowhere in

particular to go. In the mirror stands an old person wandering the neighborhood

with nothing to do. In youth, time seemed to fly like an arrow loosed from the

bow; in old age, nothing presses her except the stomach clock that marks

mealtimes. When did I grow this old? Though people say time is indifferent, she

is grateful to live anchoring the memories that fade day by day to the present.

Behold this person—her hunched back and

awkward gait, the wrinkled knuckles and lifeless skin, the faded mind that

cannot tell yesterday from ten years ago, this worn body—behold the finitude of

human aging.

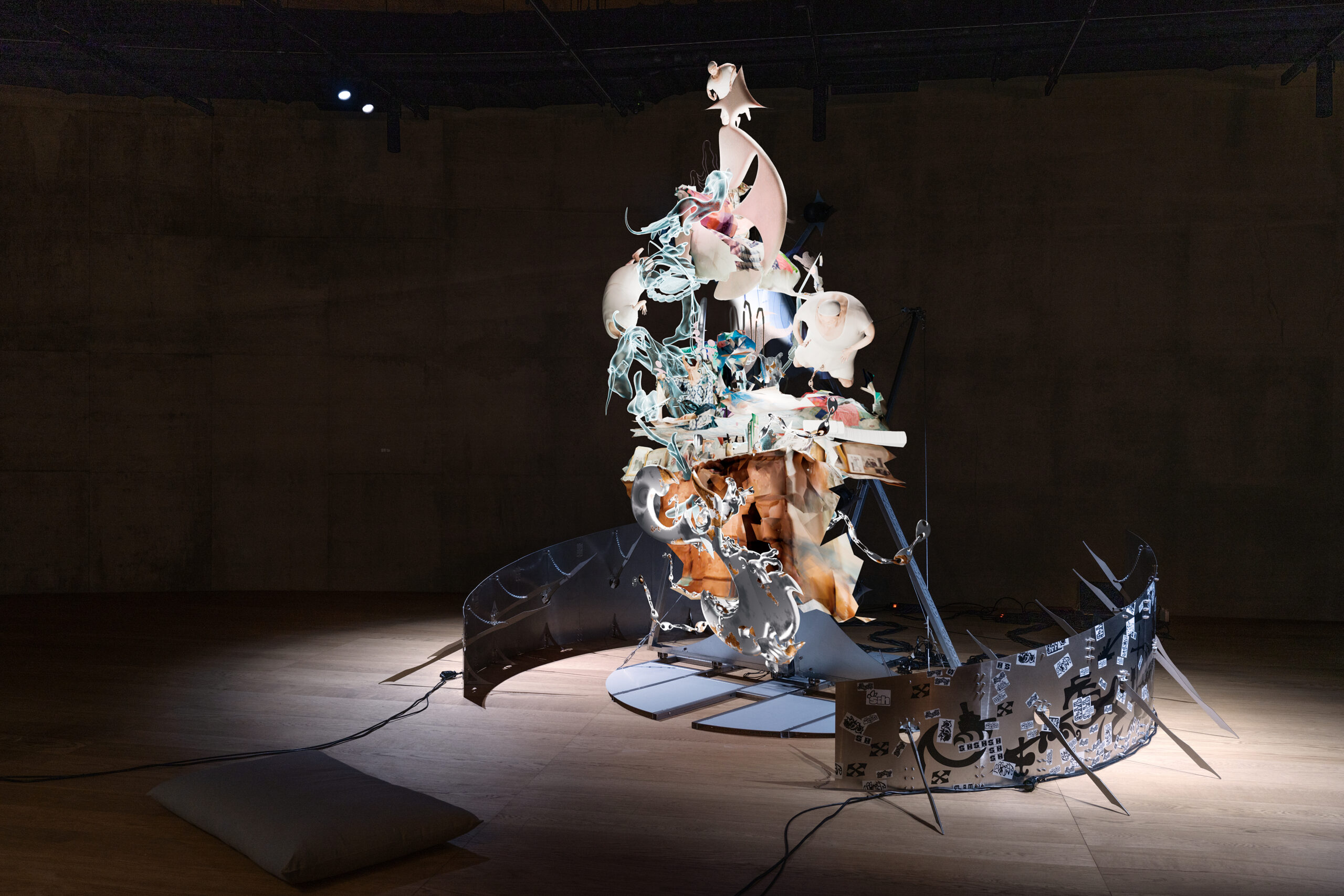

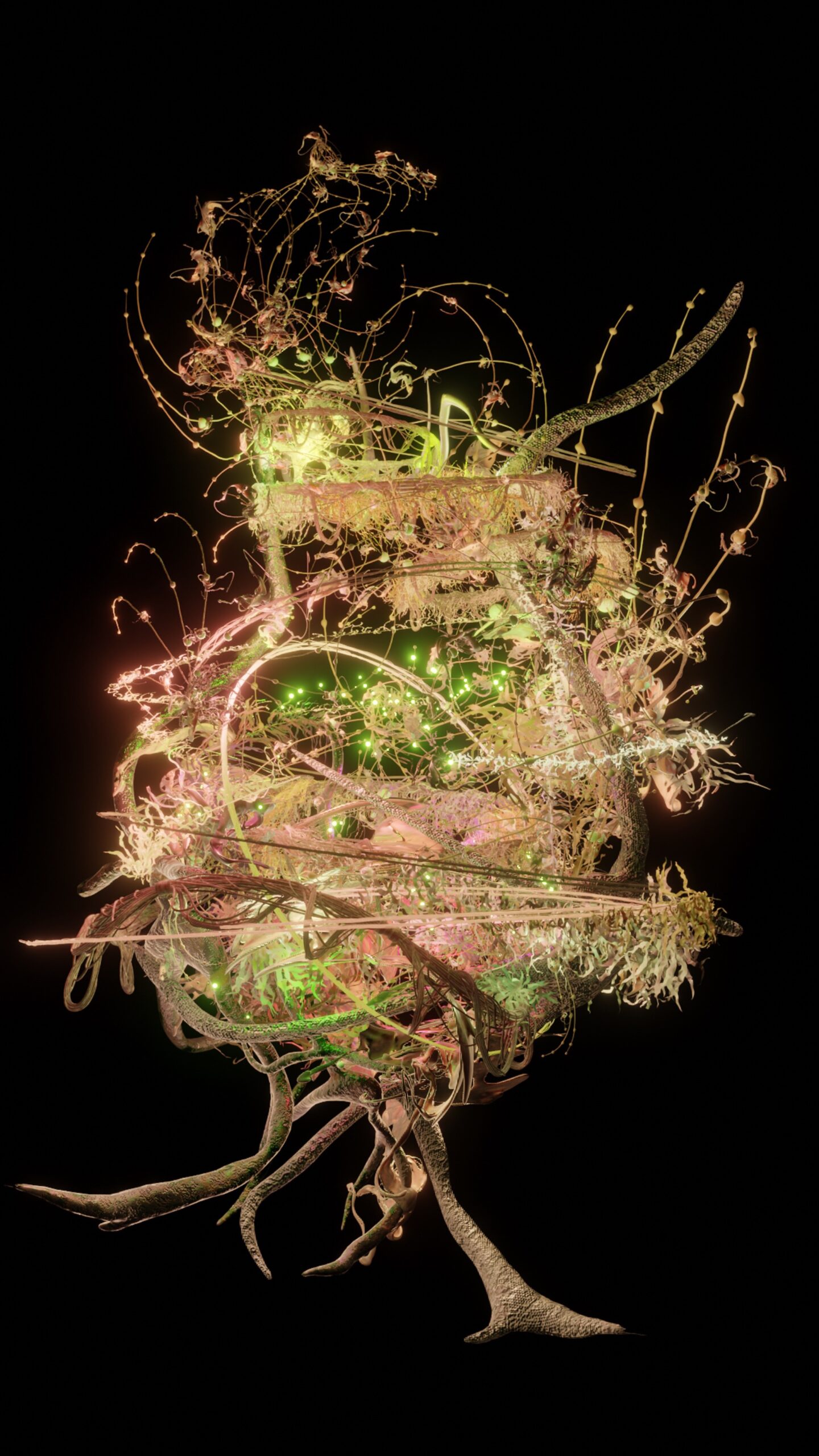

Shininho 信認好

She stands tall; the resolve felt in her back as she signals a new beginning is

noble and composed. Why does her back, facing the sea, feel different today?

Crossing seas and roaming the world, she has filled the hold with victories,

honor, and the spoils that follow. Sailing the waters as a raider, anything

that opposes her or breaks her code—living or dead—she beheads and casts into

the sea.

Thus the sea around Shininho is forever tinged red. On this ship there

is no origin, no ethnicity, no nation. Only the will of those aboard and their

desire for life—where one came from or who one is does not matter. Within this

transnational, trans-ethnic community, Captain Shininho bears a grave

responsibility as she governs and leads. She fears nothing; there is no

servility in her life. She has no mercy for traitors, yet answers with

near-infinite loyalty to those who keep their word. People called her Shininho

(信認好), “one who

believes without doubt.”

Behold this person—the reincarnation,

perhaps, of Madame Ching, the “empress of the seas” of Qing-era waters.²

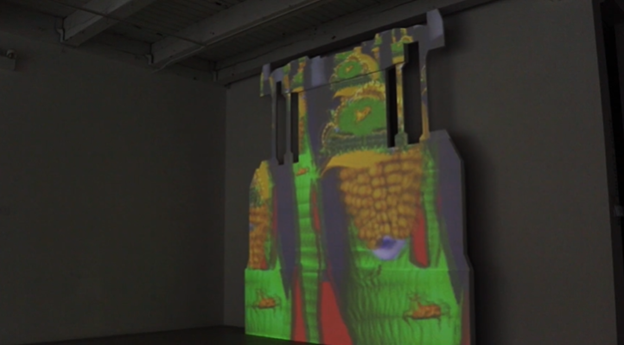

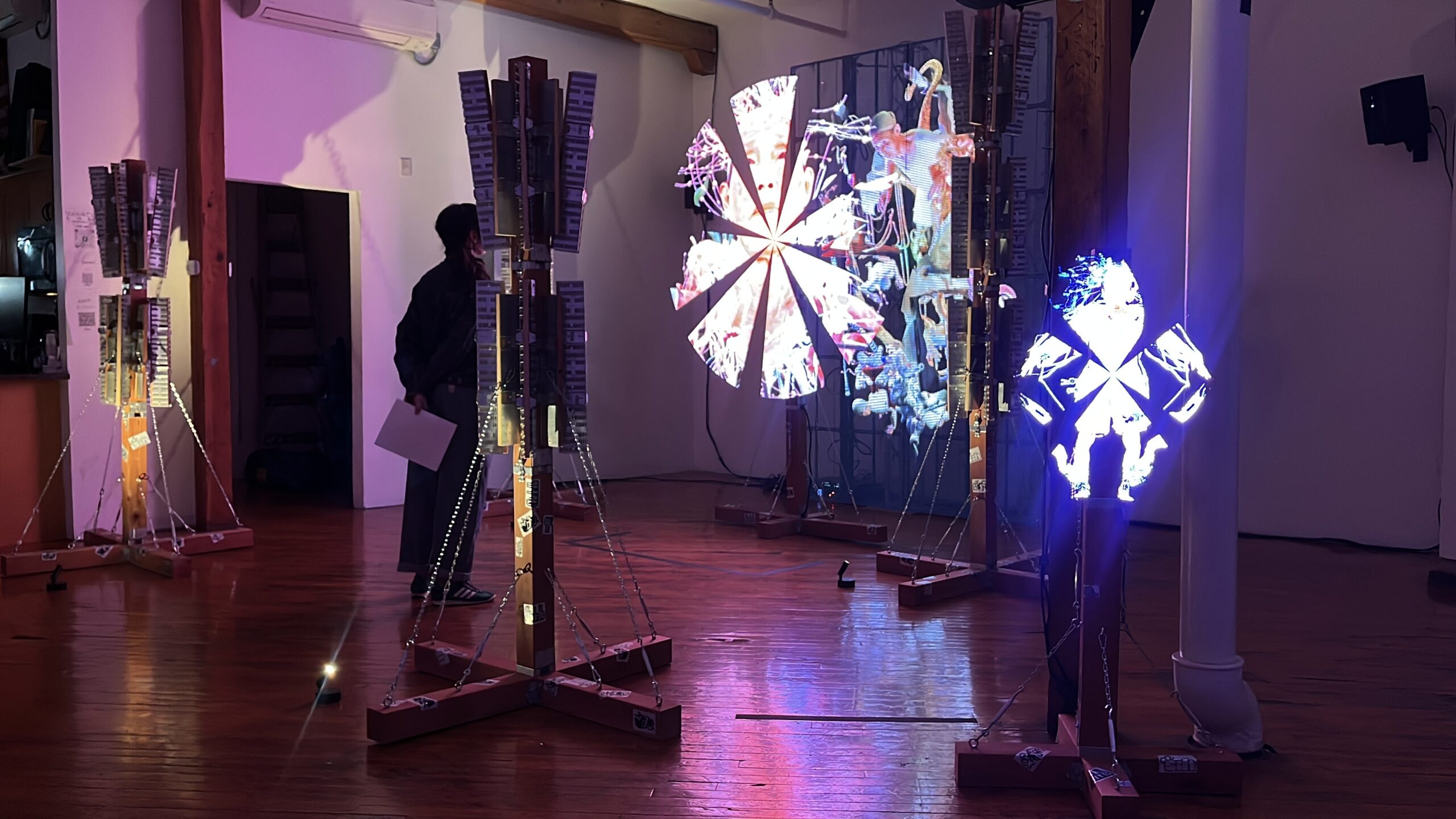

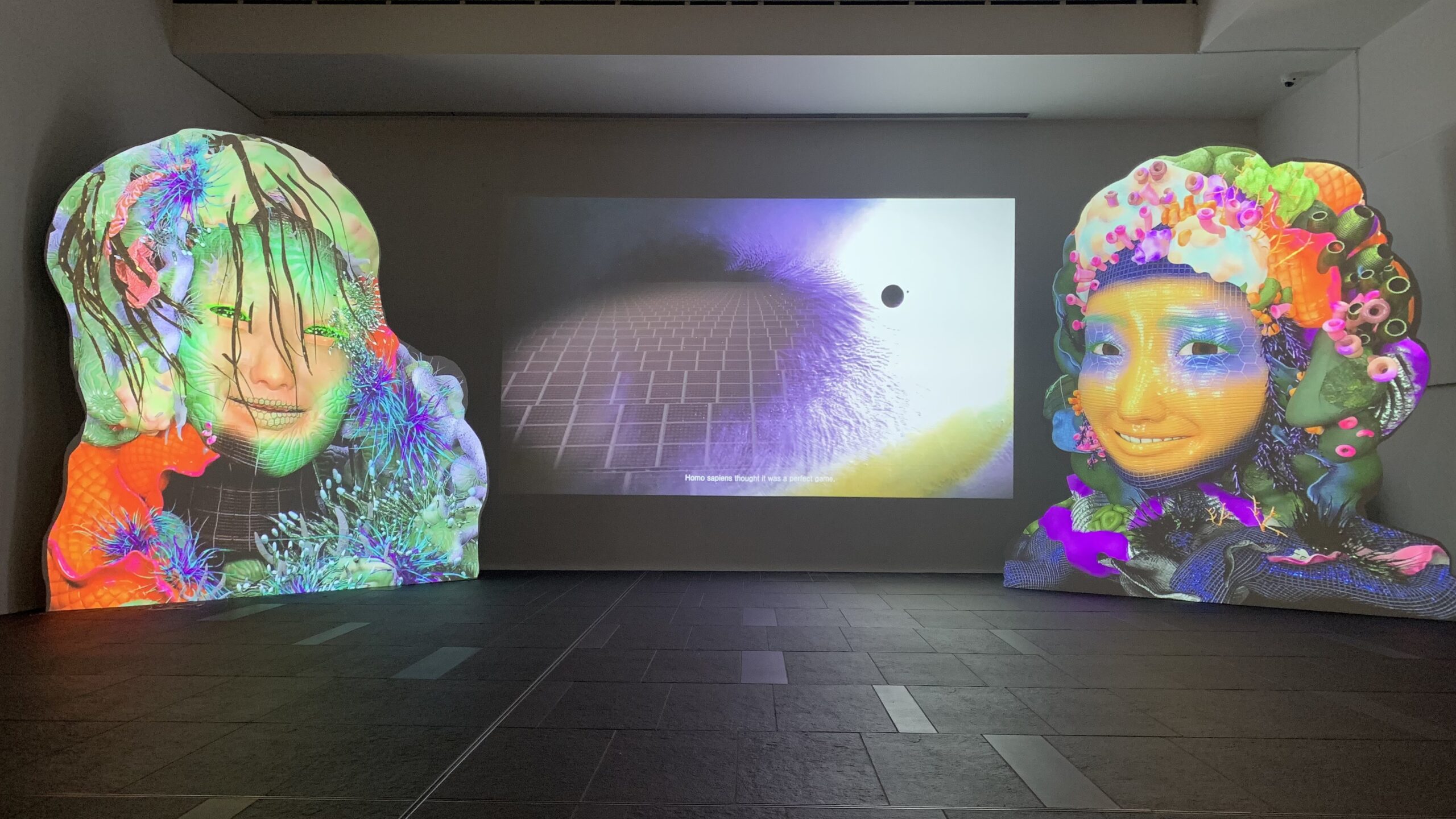

Now, Shininho and Captain Shininho have

moored for a moment at Mihakgwan. She looked back over her life but soon

stopped thinking. There is no time to think: uncharted worlds yet to visit,

adventures waiting for her, and the desires of others aboard this ship still

urge her on. She has no time. Behold—this is the person.³ ⁴ ⁵ ⁶

Text: Seulbi Lee

1. On the night of November 9, 1938, Nazi SA

stormtroopers looted and attacked Jewish shops and synagogues. Because the

glass in shop windows shattered across the streets, the incident became known

as “Kristallnacht.”

2. Madame Ching (1775–1844), from one of

China’s ethnic minorities, is known as the female pirate king who dominated the

seas of East Asia during the Age of Exploration. In Korean she is called “Jeong

Il-su.” It is speculated that “Mistress Ching,” who appears briefly on a bounty

list in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007), may have

been inspired by Madame Ching.

3. “Ecce homo” (“Behold the man”) appears in

the Gospel of John, one of the four Gospels recording the Passion of Jesus upon

his entry into Jerusalem; it is the cry of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor,

addressing the crowd while presenting Jesus in a purple robe and a crown of

thorns.

4. Pilate’s cry—“Behold the man!”—introducing

Jesus before his crucifixion was a religious icon beloved by many late medieval

masters, including Titian (Tiziano Vecellio).

5. Nietzsche’s final work, Ecce Homo,

was written in 1888 and published in 1908. As an autobiographical text, it is

considered essential for understanding his often difficult writings despite its

brevity. Including the preface, its chapters are titled “Why I Am So Wise,”

“Why I Am So Clever,” “Why I Write Such Good Books,” etc. (See: Friedrich

Nietzsche, The Case of Wagner · Twilight of the Idols · The Antichrist ·

Ecce Homo · Dionysian-Dithyrambs · Nietzsche contra Wagner, trans. Baek

Seung-young, ChaekSesang, 2016, pp. 321–375.) The title Ecce

Homo borrows Pilate’s line from the Gospel of John. While Pilate points to

Jesus as “the man,” Nietzsche sets himself in counterpoint to Jesus. From

placing himself on the same plane as Christ to the boundless self-confidence

and self-praise that follow—this stance stems from opposition and critique

toward Christianity’s emphasis on humility and social conformity. Some read

this near-delusional confidence as a harbinger of the madness that overtook

Nietzsche in his final years, but within his philosophy it can be read as an

affirmation of life and pride in existence.

6. Inspired by Nietzsche’s work, British SF

writer Michael Moorcock published the novel Behold the Man (1969).

Its protagonist, whose life is going nowhere, travels by time machine to A.D.

28 to seek Jesus’s teachings, only to find Jesus and the Virgin Mary far from

the figures described in Scripture—no better off than the protagonist himself.

By the end, having accidentally taken on the role of Jesus in the Gospel

narrative, the protagonist is nailed to the cross, regretting everything.

(Michael Moorcock, Behold the Man, trans. Choi Yong-joon, Sigongsa, 2013.)

Sharp in its skepticism toward Christian doctrine, this anti-Christian novel

won the Nebula Award, one of SF’s major prizes, in 1967.