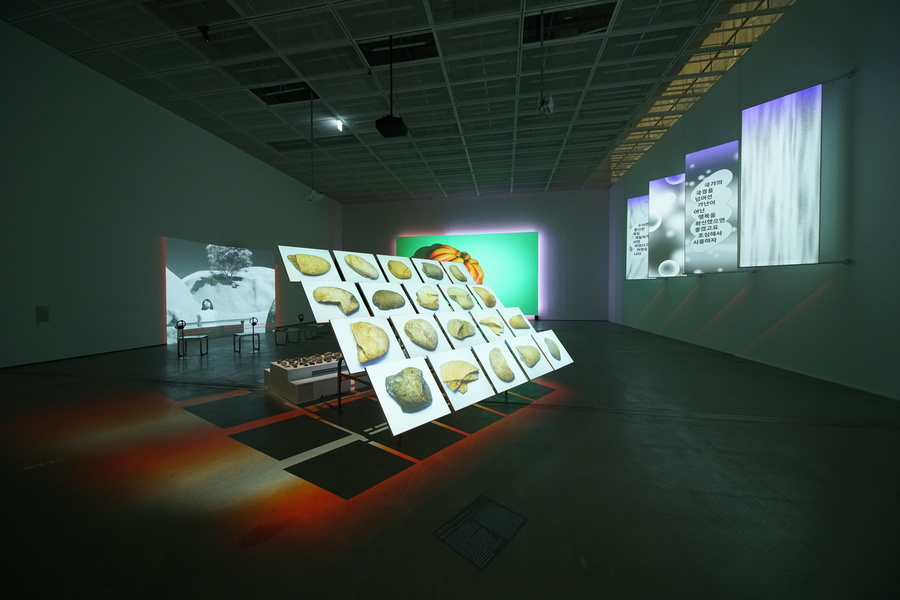

There is a photograph. I glimpsed

it on Twitter years ago, and I have never been able to find it since. Perhaps

it is an image without substance, a product of my imagination. The photo

depicted various stones—large and small—on a beach, wet and glistening:

pebbles, gravel, and round cobbles. The photographer, presumably on a walk,

must have crouched down to capture something. At first glance, the image

appeared to be a harmonious composition of colorful, naturally shaped stones.

Only upon closer inspection could one notice a fragment of a printed plastic

panel—flooring material designed to resemble stones—camouflaged beneath them.

The synthetic stone pattern was seamlessly integrated among the natural rocks,

forming an uncanny unity. Judging by its slightly faded color and irregular

edges, it was not something deliberately placed. Rather, it seemed to have

drifted ashore after floating on the sea—an authentic found object. This image

can be seen as an episode or allegory of contemporary visual culture that illustrates

the hybrid harmony between nature and the artificial.

For modern viewers, witnessing

artificial objects blend seamlessly into natural ones to form a harmonious new assemblage

has become a familiar sight. To borrow the language of Bruno Latour, this may

be just a simple example of the proliferating hybrids of modernity. Over tens

of millions of years, massive rocks break down into beach pebbles, while

remnants of organisms buried underground over similarly vast periods are

transformed into petroleum, which in turn becomes plastic fragments. Today,

these two materials lie side by side, providing an indistinguishably similar

visual experience. The everyday presence of artificial objects like computers,

mobile phones, and electric vehicles often obscures the fact that they are

composed of natural materials. Nature and culture are already so entangled that

even the binary distinction between them holds little inherent meaning.

Like any other natural substance,

rocks neither despair nor harbor vague hope; they endure the Earth's timeline

that spans billions of years. Over the course of deep time, a single boulder

may have undergone multiple cycles—transforming from rock to pebble to sand to

clay and back to rock again. Even if we worry about acid rain corroding it, the

rock will likely retain its solidity long after humanity has gone extinct,

perhaps until a new form of life—potentially non-biological—dominates the

Earth. But perhaps such a judgment is too hasty, too modern. What if rocks and

stones are not so enduring after all? What if all of Earth’s stones are

mined—used up either for extracting the materials necessary for digital media

devices or as sources of energy? Then the natural rocks might be replaced by

synthetic ones, or merely images resembling them. In contrast to the time of

the Earth and stones, humanity has, in just a couple of hundred years,

accelerated and compressed the vast geological process of “deep time” through

development, mining, and consumption. In pursuit of energy, modern humans have

indiscriminately mined fossil fuels such as coal and oil, along with minerals

like copper, aluminum, cobalt, silicon, nickel, and lithium for manufacturing

and powering all kinds of industrial products and digital devices.

Between Data Extraction and

Resource Mining

Recently, many have referred to

data as a “new natural resource,” and this is more than just a metaphor. While

data isn’t literally mined from the ground, it serves as the raw material that

feeds global digital platforms and algorithmic networks—keeping them alive and

functioning. Data is omnipresent, and once its necessity is recognized and

measurement devices (sensors) are developed, it becomes an infinitely mineable

substance. Although the very existence of data—whether it is an object, a

concept, or an event—remains ambiguous, there is no doubt that anything in the

world can be turned into data, making it an exceptionally plastic resource.

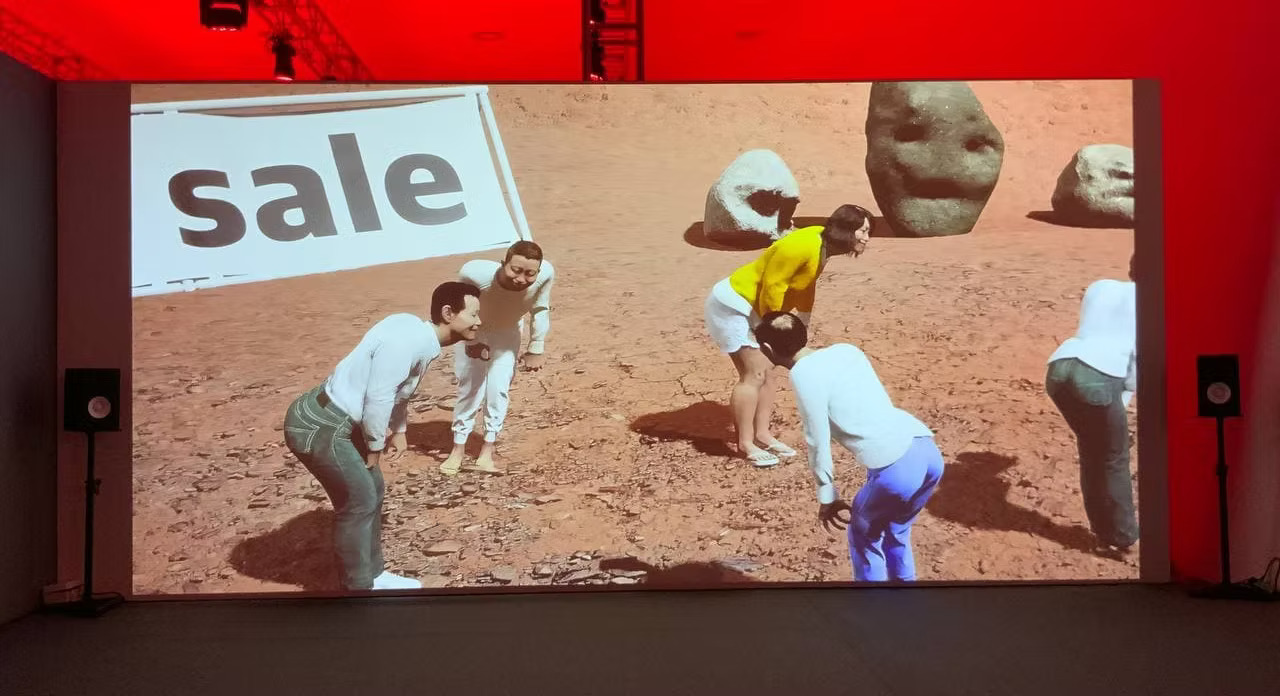

Just as the fusion of natural

stones and artificial stone patterns has become “natural” to us, so too has the

combination of silicon (as material) and algorithms (as data). The transition

from industrial capitalism to cognitive capitalism has occurred through the

inevitable linkage between rare minerals extracted from rocks and the data that

can be extracted from every facet of the world. While digital or cognitive

capitalism seems to reduce everything into the immaterial and intangible—such

as data—detached from the physical earth and matter, in truth, it demands even

deeper entanglement with rocks and the planet.

Matteo Pasquinelli summarizes

this technological and social condition with the concepts of the “carbosilicon

machine” and “cyberfossil capital.”¹ Our society

is moving toward a cybernetic world where everything is automated through the

integration of energy-producing fuels, materials that make up semiconductors,

and information that gives form to things and energy alike.

Critical AI researcher Kate

Crawford begins her book Atlas of AI² from the foundational

layer—“Earth”⁴—drawing on Benjamin Bratton’s planetary-scale platform model in The

Stack.³ The computational reality in which everything has become

calculable is built across multiple layers and scales: energy and minerals,

cloud infrastructure, smart cities, the Internet of Things, user interfaces,

and AI algorithms. The abstract and immaterial systems of software and

algorithms are layered directly above and below the strata where energy and

minerals are mined. In Crawford’s collaborative project with Vladan Joler, Anatomy

of an AI System,⁵ their holistic analysis of AI also begins and ends with the

Earth. “Each

product included in the extended network of an AI system—from network routers to batteries

to microphones—is

made of elements formed over billions of years. From the perspective of deep

time, we are squeezing the history of the Earth to manufacture technological

artifacts used for mere years. […] Geological processes mark both the beginning

and end of the entire lifecycle, from ore extraction to disposal in electronic

waste dumps.”

From this perspective, Sandro

Mezzadra and Brett Neilson attempt to redefine the dominant paradigm of

contemporary capitalism by expanding the meaning of “extractivism.”⁶ Historically, the term referred

to the imperialist process by which natural resources and living beings

(including humans) were forcibly displaced and exploited—mainly in the Global South—for value production and

accumulation. But now, the scope of “extraction”

is being broadened to encompass practices like data mining and the commodification

of human life itself in the era of biocapitalism.

In other words, from the

extraction of natural resources for manufacturing and sustaining AI devices, to

the mining of data for training and refining AI algorithms, and further to the

exploitation of human data labor that enables AI’s completion, the mechanisms

of contemporary capitalism are all fundamentally extractivist in nature.

Furthermore, given that today’s mining, extraction, and exploitation still

overwhelmingly take place in the Global South and peripheral regions, it must

be emphasized that the global inequality of capitalism remains historically

unchanged.

The expanded notion of

“extractivism” proposed by Mezzadra and Neilson is vividly visualized through

the maps meticulously rendered by Joler and Crawford. In Anatomy of an

AI System, they trace the macro and micro pathways of a small AI

speaker device—Amazon’s Echo (equipped with the Alexa system)—from the mineral

elements it is made of, to how its algorithms are trained and operated through

human labor, and finally to how it is dismantled and buried in the earth after

disposal.⁷

Through this comprehensive

diagram, we come to realize a crucial, yet often overlooked fact: even

something as seemingly immaterial and abstract as data—or AI

algorithms—requires a material (mineral-based) foundation to exist, function,

and circulate in digital form. This includes everything from generation,

storage, computation, measurement, to mobility. The diagram reveals that mining

and disposal are unavoidable components of the data-AI cycle.

Within a single AI system, the

extraction of resources, labor, and data occurs simultaneously, generating

value through a multi-layered process of exploitation and extraction. This

structure mirrors the Marxist dialectical triangle of labor force, means of

production, and product—a fractal pattern akin to a Sierpiński triangle, repeating complexity at every level. Whether at a

rare earth mineral mining site in the Congo, an Amazon voice AI manufacturing

plant in China, or a household using digital devices, it is impossible to

escape this triangular dialectic.

Extraction of Knowledge and the

Mind