22)

This brings us to the challenge of conceptualizing a practical

model that poses questions and triggers awareness—a model we propose to call

the "model of ignorance." At first glance, it may seem that large

language models like ChatGPT are incapable of responding with "I don't

know." However, they actually can. These models are trained on vast

amounts of text and are also designed to generate responses that simulate

human-like reactions, including acknowledging uncertainty or lack of knowledge.

The domains in which GPT typically replies with "I don't know"

closely mirror human limits, with the exception of emotional or cognitive

overwhelm:

- Lack of knowledge or expertise

- Uncertainty or ambiguity

- Speculation or future predictions

- Personal opinions or experiences

- Confidentiality or privacy concerns

- Emotional or cognitive overload

But we must envision another model of ignorance. Not merely a

model capable of answering with "I don't know," but rather something

akin to Jacques Rancière’s notion of the “ignorant schoolmaster.” It is a model

not designed to augment intelligence and capacity, but one that acknowledges

and gropes through the limits and uncertainties of our knowledge. Rather than

being preoccupied only with what can be analyzed and modeled, this model

emphasizes the necessity of recognizing the unknowns and gaps embedded in knowledge.

Instead of demanding direct answers from AI, it aims to collaboratively

generate questions, synthesize diverse perspectives, and enhance intellectual

autonomy.

Rancière’s “ignorant schoolmaster” advocates for a pedagogy rooted

in a shared state of ignorance. Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster:

Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, trans. by Yang Chang-ryeol, Gungri,

2016. It is a perspective that regards ignorance not as a deficiency or

weakness but as a catalyst for intellectual growth and critical thinking. By

embracing ignorance, intellectual autonomy can be cultivated. This approach

allows learners to reach deeper understanding through active engagement,

questioning, and independent pursuit of knowledge.

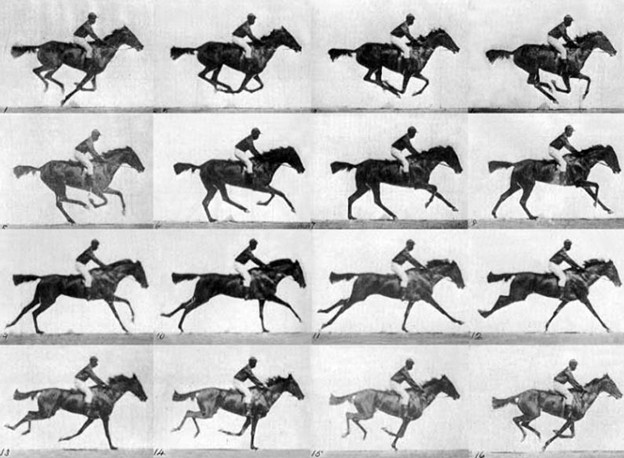

To observe, to repeat, to verify, to fumble—like solving a riddle.

Rancière suggests that this very fumbling is the true movement of intelligence,

a genuine intellectual adventure. Couldn’t a model that disrupts the state of

"not knowing ignorance" be what we call a “model of ignorance”?

23)

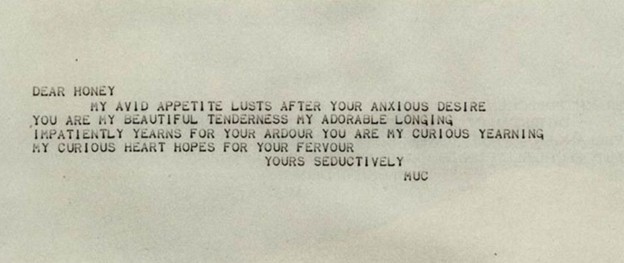

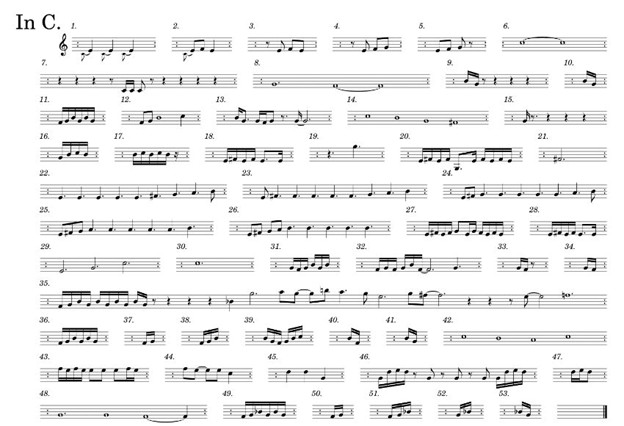

The idea of developing an AI based on the concept of the

"ignorant schoolmaster" may seem counterintuitive, yet it is

profoundly necessary. Such a "model of ignorance" could paradoxically

become a beacon of knowledge in an age oversaturated with information. By

embracing gaps and absences, it may enable deeper and more holistic forms of

learning—just as silence, no less than notes, lends depth and resonance to the

melody of knowledge.

Juxtaposing GPT's information-centric approach with the

"model of ignorance" reveals a unique perspective—one that urges us

to rethink our understanding of intelligence. The key lies not in finding the

right answers but in maintaining an open stance toward the countless things we

have yet to comprehend, with courage to question and doubt.

Some may argue that applying a "model of ignorance" to

AI is regressive. Yet, in truth, it becomes a driving force propelling us

toward a future where the pursuit of knowledge never ends. In a world where AI

might provide answers to all our questions, we must ask ourselves what it is we

truly seek. Mere productivity? Or deeper understanding? Productivity, by

nature, is a double-edged sword. While technology, including AI, allows us to

accomplish more in less time, we must question whether the depth of understanding

is keeping pace with this acceleration.

The tension between speed and depth lies at the heart of the

modern riddle. Today, access to information is easier than ever, yet profound

understanding becomes increasingly elusive. It is time to shift focus from the

quantity of knowledge to the subtlety of understanding, and to reassess the

metrics of intellectual achievement. Embracing a “model of ignorance” does not

reject the convenience of modern technology; rather, it affirms the

interstitial spaces of ambiguity and seeks to complement them through inquiry.

24)

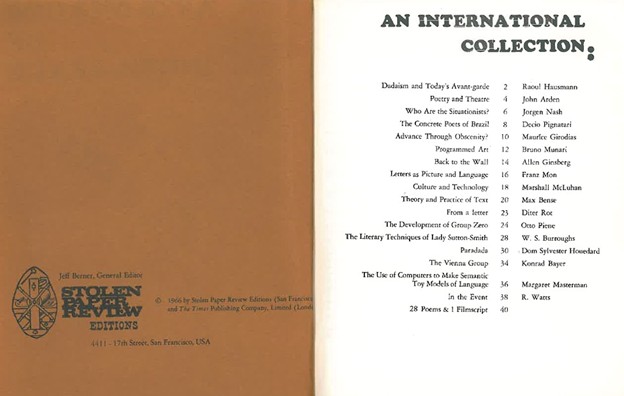

Returning to Margaret Masterman, let’s examine another of her

claims: “Language, at least in part, has its present form because it was

created by a creature that breathes at fairly regular intervals.” This is noted

as a rough summary of her argument. Wikipedia contributors. “Margaret

Masterman.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Margaret_Masterman&oldid=1154803664

Since Masterman did not fully elaborate on this idea, the following statements

may be closer to a personal hypothesis.

To restate her claim more operationally: language is a complex

system shaped by the physical and biological constraints of its users. The

rhythm of breathing, limitations of vocal cords, brain structure, even the

auditory organs that receive spoken language and the waves of air—all

contribute to how language is formed and used. These physical limitations are

integral to understanding language. Spoken language is the product of an

organism and its surrounding physical conditions—and written language is, to some

extent, the same.

This reminds us to consider the conditions of reality in which we

exist. It brings to mind Rodin’s assertion that time never truly stands still

and invites us to oscillate between what can be modeled and what remains a

void, viewing large language models from that vantage point.

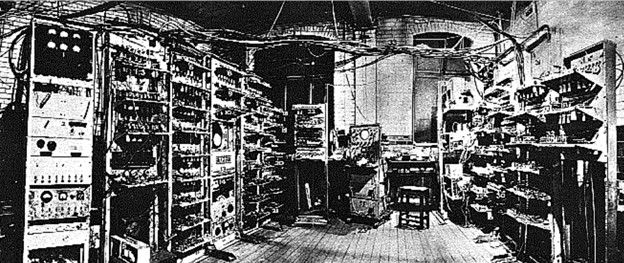

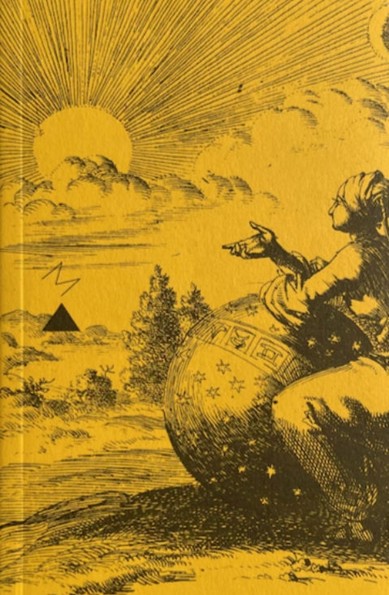

Masterman sought to understand computing through the metaphor—or

model—of a “telescope for the mind.” Just as the telescope in the 17th century

reshaped humanity’s understanding of its relationship to the world, today,

computing and AI prompt a reevaluation of our perception.

If natural science was reinvented through the telescope, AI might

be tied to the reinvention of our cognitive systems. Not merely through

steroidal boosts in productivity enabled by statistically synthesized outputs,

but through something related to alternative cognitive paradigms. In this

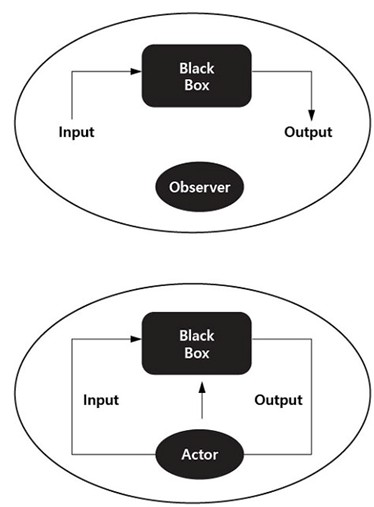

context, viewing large language models as black boxes or models of

ignorance—hypotheses of perception—could help disrupt conventional thinking

about language, cognition, and the relationship between humans and machines, and

open up new cognitive models.

25)

The metaphor of the “telescope for the mind” sparks intriguing

thoughts. A telescope brings distant stars closer but does not tell us what to

think about them. Likewise, while AI holds tremendous potential, it should be

seen not as a complete source of knowledge but as a mediator that brings

knowledge closer and enables its exploration. The essence of the “model of

ignorance” is not to reduce AI’s level of knowledge, but to harness its

potential to foster questioning, exploration, and curiosity.

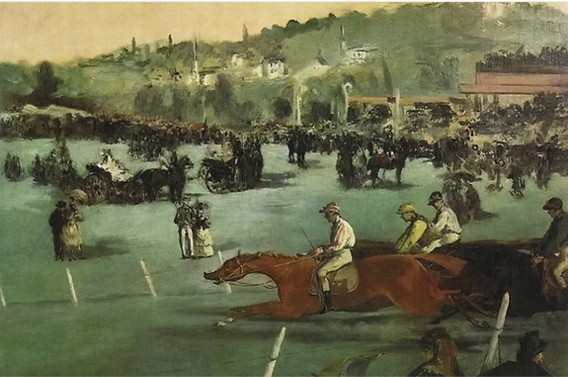

Seeing AI not merely as a tool but as a medium places it in a

broader cultural role, akin to literature or art. In such an aesthetic space,

ambiguity effectively invites contemplation and reflection. This raises the

question: can AI, as a medium, trigger such aesthetic spaces as a “model of

ignorance”? Like a novel or piece of music that arouses curiosity, can it use

uncertainty not to suppress but to deepen and channel it into reflective

understanding?

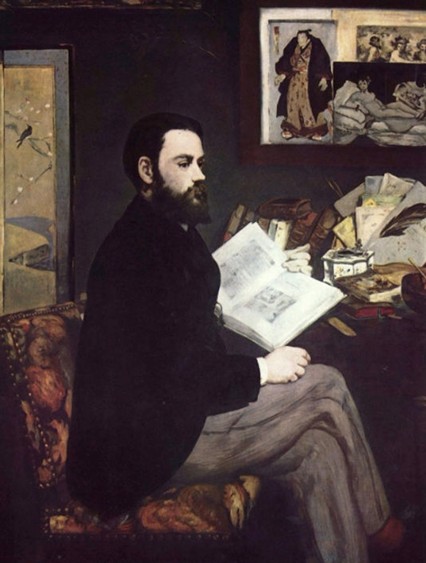

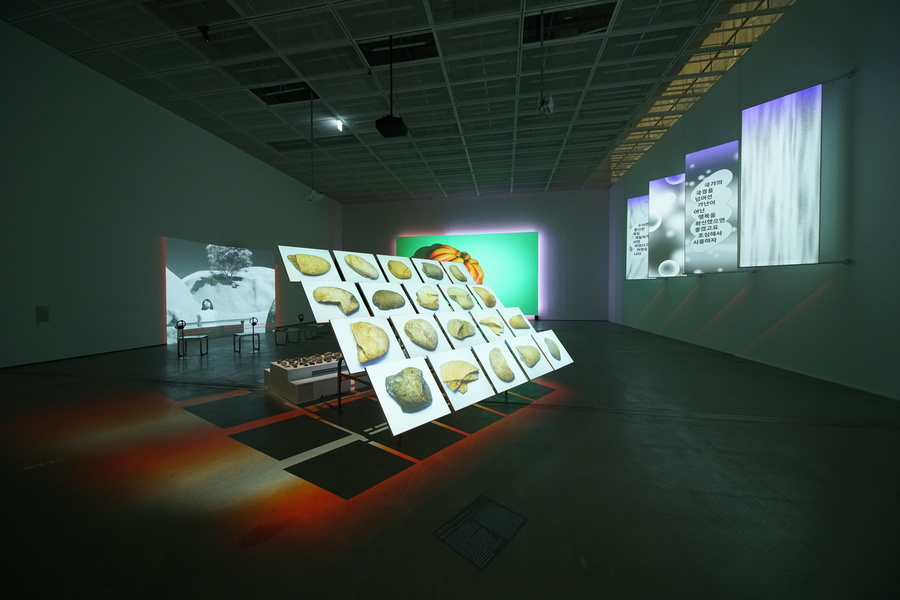

All the artworks and concepts explored here offer potential to

reframe our perspective on the vast digital ecosystem. Within it, the dynamism

of digital art, the oscillation between what can and cannot be modeled, and the

rich subtleties of language intersect. Our task may be to not avoid but embrace

the unknown and ambiguous, using the “model of ignorance” to propel deeper

inquiry.

-

This essay expands on Productivity and Generativity – GPT as a

Drunken Poet (Gyesung Lee & Binna Choi), presented at a 2023 talk at

Forking Room.

Gyesung Lee, through translation and writing, seeks to explore not

the utilitarian but the poetic aspects of large language models and

computer-generated texts. He translated Pharmako – AI (Ghost Station, 2022),

Dialogue with the Sun (Mediabus, 2023), and contributed to Context and Contingency

– GPT and Extractive Linguistics (Mediabus, 2023).

Binna Choi works with Unmake Lab and participates in Forking Room

as a researcher. Her interests lie in overlapping developmental histories with

the extractivism of machine learning to reveal the sociocultural, ecological

conditions of the present. Recently, she has been working with the concept of

“general nature” in relation to datasets, computer vision, and generative AI to

address issues of anthropocentrism, neocolonialism, and catastrophe.