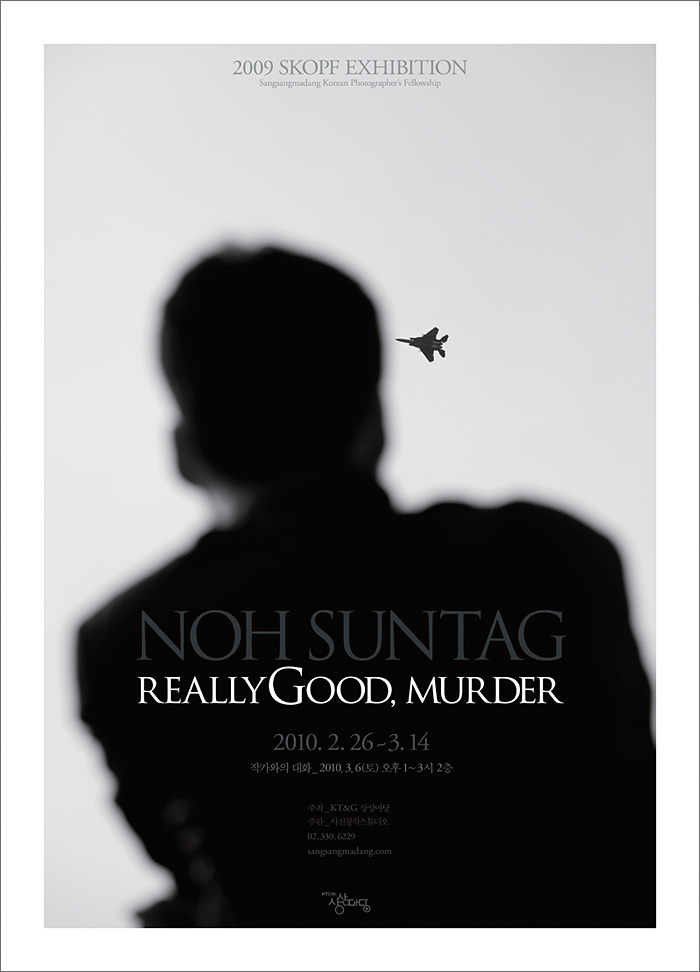

2. The Weapon Experience

Perhaps

the most iconic image from Really Good, Murder depicts the

small hands of a child gripping the handle of an M60D machine gun mounted on a

display helicopter, while the child’s father, holding a camera, grips the

barrel from the opposite side to take a photo. Neither the child’s nor the

father’s face is visible—but there is a third, unseen figure behind the camera:

Noh Suntag himself. The image thus forms a triangular composition of

“shooting”—in both the photographic and ballistic sense.

Although

neither a camera nor an unloaded gun inflicts immediate physical harm, both can

cause long-term symbolic damage. It would not be far-fetched to call this a

“really good murder.” The photograph, self-reflexive in nature, mirrors both

Noh’s critical gaze at the arms fair and his own awareness as a photographer

constantly aiming his lens at others.

Children

frequently appear throughout the series, escorted by their parents through

gleaming displays of advanced weaponry. When juxtaposed with instruments of

war, these children create a disquieting tension—but they also share something

with the weapons themselves: both react simply and instinctively. It is

chilling to imagine that the child who “learns” from such exhibitions might

later reenact what they witnessed.

For

Noh, whose long-standing theme is institutionalized violence, the sanitized

spectacle of a national defense exhibition—where instruments of destruction are

glorified as symbols of technological excellence—becomes the perfect stage for

a darkly humorous composition. Like the Air Force cadet’s anguish, the weapon

the child handles is indeed a well-made machine—a “good” one—yet its ultimate

value lies in its efficiency as a killing device. Such contradictions are

masked by myth-making, and the arms fair itself becomes the theater of that

myth.

One

particularly absurd image captures a special forces officer assisting a

high-school girl as she practices throwing a mock grenade. The overlapping

posture of the young man and woman carries an erotic undertone that transcends

mere training intensity. The grenade’s explosive potential merges with the

soldier’s repressed vitality and the girl’s short skirt and gold sneakers,

creating an uncanny, unsettling eroticism.

3. The Languor of the Defense Fair

The

lethargic atmosphere of the arms exhibition reaches its peak in an image of an

armored soldier standing nonchalantly with his hands clasped behind his back

before an M2HB heavy machine gun—its barrel coincidentally aligned with the

back of his head. Noh’s camera captures this moment of ironic peril, as though

reminding us that the weapons aimed outward inevitably turn back upon their

wielders.

This

sentiment recalls the anti-war poster What Goes Around Comes Around,

which won the top prize at the 50th Clio Awards, designed by Korean artist

Jeseok Lee—a message deeply resonant with Noh’s own.

Noh’s

photojournalism, which has long documented clashes between opposing forces,

often features the myriad “weapons” each side employs—batons, flags, clenched

fists, microphones, card sections, cups with candlelight, riot shields, and

sometimes cameras disguised as benign tools. Yet the Really Good,

Murder series marks a rare instance where real military hardware

dominates the frame, following the precedent of his Black Hook Down

series depicting helicopters and fighter jets over Daechuri.

By

rhythmically reconfiguring these instruments of war on photographic paper, Noh

aestheticizes political warning. His archive of protests and conflicts, while

deeply engaged with the emotional center of violence, rarely indulges in

pathos. Even when his work approaches abstraction—as in That Day at

Namildang III—its poignancy remains understated.

In

this exhibition, we confront his carefully composed images of rhythmic,

aesthetic, and quiet violence—and we shudder.

The

rhythmically aesthetic yet quietly violent nature of Noh Suntag’s photographs

can be traced across series such as Red Frame, which dryly

captures North Korea’s regimented Arirang mass games, and the strAnge

ball, which reduces the blood-soaked Daechuri incident into a minimal

circular radar form. His avoidance of direct expression stems from “the need to

somehow cook the awkwardness and roughness that arise from frontal

confrontation” (the strAnge ball, artist’s note, 2006). He

must have sensed that raw, unfiltered photojournalism no longer suited the

spirit of the times.

Unlike

most artists, Noh filled the catalogue for this solo exhibition with unusually

extensive writing—as he has done in all his photobooks—perhaps out of concern

that the aesthetic refinement and metaphorical depth of his work might alienate

communication, leading him to compensate through lengthy verbal elaboration.

P.S. Bertolt

Brecht, who habitually clipped war-related newspaper photographs with scissors

and glue, published Kriegsfibel(War Primer),

adding four-line verses to his selected images. The second poem in this

collection of 69 photographs shows laborers carrying massive steel plates,

accompanied by the following verse:

“Hey

brothers, what are you making there?” “An armored car.”

“And from these stacked iron plates?”

“Bullets that pierce armor.”

“Then why do you make all this?” “To make a living.”

Perhaps

Brecht, too, worried that even a well-edited press photograph might fail to

convey meaning fully.

This may explain why Noh Suntag’s photographs are both timely and poetic at

once.