As

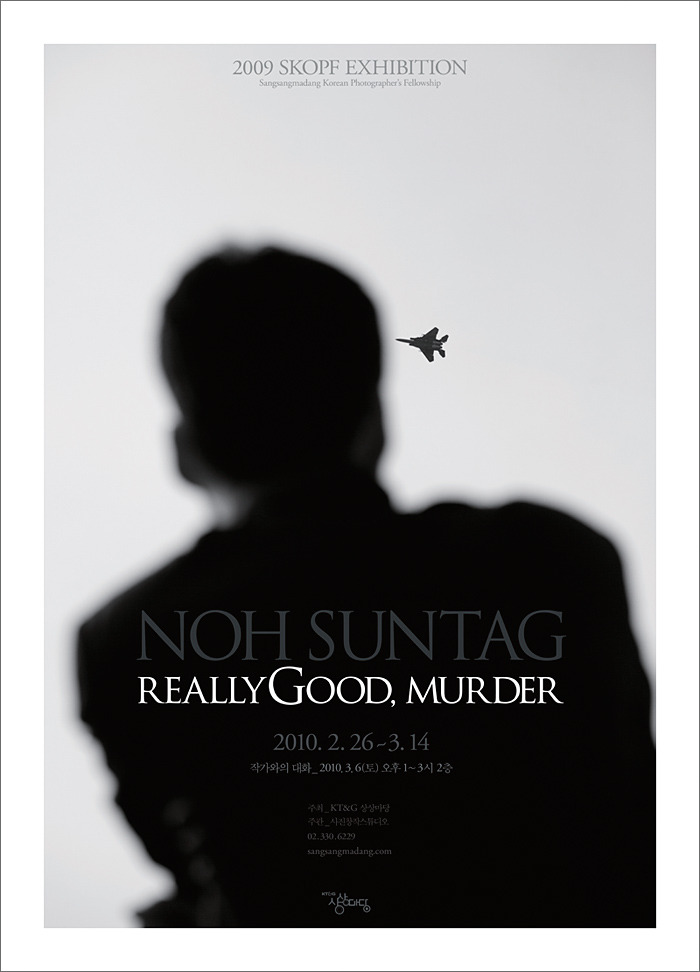

one looks at the work of Noh Suntag, one feels as though the figures in the

photograph have become frozen in that moment forever. They may appear

taxidermized in a sense, or give a cold impression. “I’m deliberately trying to

create a disconnect between the emotional temperature and the temperature of

the work,” the artist has said.

Noh Suntag: The

coordinates for my work are situated in three axes. The first axis is the axis

of activity on the ground. The things I do with the people who appear in my

photographs could be described as “solidarity,” or it could be called

“activism.” The second axis is within and outside the field of journalism. The

places I occupy are typically the settings of urgent complaints or outcries. I

see it as being of paramount importance to let more and more people know about

the things that are happening here and now.

The third axis has to do completely

with my own work as an artist. It’s something that demands a long-term

perspective and objectivity. I try to distance myself from methodologies

involving appeals, emotions, rage, or persuasion. Each one of these three axes

is very important to me. The first two of them have become something like

alibis or nutrients that enable the third. There’s an expression in

Korean, bulgageun bulgawon, which means, “You shouldn’t get too

close, but don’t stand too far away.” It’s a really great saying, but not a

principle that I wish to obey.

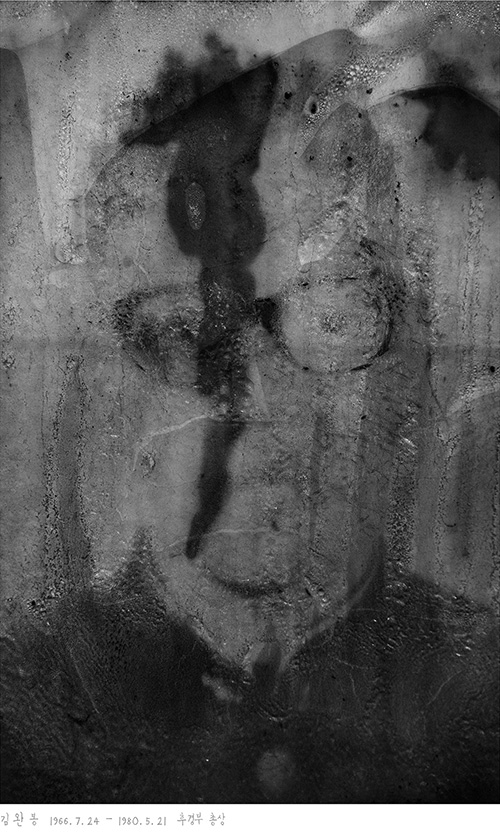

Noh

Suntag has described himself as a “witness who accepts a witness’s

responsibility to testify, but to give testimony that is inevitably flawed in

some way.” In this way, he uses his own unique methods to quietly share his own

story about the reality he witnesses. The many accounts he has left behind with

his photographs will provide viewers with an opportunity to develop their own

different interpretations. The interpretations they sense as they see his work

may or may not be the ones the artist intended—but each one will be a “hair”

unto itself, a different kind of witness to record the reality.

*This piece is part of a series focusing on four artists for a visual

arts criticism/medium matching support program by the Korean Arts Management

Service.

1)Noh Suntag, “The Meaning I Saw Then,” Hwanghae Culture Vol. 81,

2013, p. 450.

2)Noh, ibid., p. 448.

3)“So it must have been about seven or eight years.

What do they take us for? It was a round thing placed way up high, so we

figured it was a water tank or something. Later on, people said it was an oil

tank or some kind of antenna. We just come up with our things about it. It’s

comforting to think it’s just a big ball, you know? There were even times when

I’d look at that ball from a distance and feel pleased about it, thinking,

‘That’s our neighborhood.’” Noh Suntag, "the strAnge ball," Shinhan

Gallery, 2006, p. 2.

4)“For the operation that day, the government mobilized

around 12,000 police officers from 115 squadrons, 2,800 people from the capital

corps and the 700th Special Assault Regiment, and 700 employees from private

security companies. The tiny farming village was transformed instantly into a

battlefield.” Noh Suntag, “Daechu-ri, 36.5°C,” Hwanghae Culture Vol. 52, 2006,

pp. 273–274.

5)Noh Suntag, “Bloody Bundan Blues,” Gwangju Museum of

Photography, Bloody Bundan Blues, Gwangju Museum of Art, 2018, p. 18.

6)“Evidence indicates that at the time of the North

Korean artillery attack on Yeonpyeongdo Island on Nov. 23, 2010, military

intelligence organizations detected signs of the attack ahead of time and

alerted over 20 agencies including the Blue House and Ministry of National

Defense, but were ignored by the administration and military command. The

Ministry of National Defense was also found to have concealed the preliminary

intelligence about the attack in a meeting of the National Assembly National

Defense Committee the day after it occurred.” The Hankyoreh, December 14,

2012.(http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/politics_general/565396.html#csidxcb519cbbdcdcf5790c350ed663d3130;

accessed on October 15, 2018.)

7)Noh, “Bloody Bundan Blues,” p. 19.

8)Atsumi Tanabe & Noh Suntag, “I Am a Living You,

and You Are a Dead Me,” Noh, Forgetting Machines, Chungaram Media, 2012, p.

205.

9)Tanabe & Noh, p. 210.

10)Tanabe & Noh, p. 218.

11)Tanabe & Noh, p. 207.