1.

The world may be thought of as a huge mass made up of countless translucent

layers. We each live and die alone in our own thin little layer, widely

separated from people living different lives around the world. Perhaps the

notion of a shared existence is merely a figment of our imagination.

What

divides us from others is not merely physical distance; we often seem to be

living at entirely different speeds, in different times. Some people, citing

the global triumph of democracy and the market economy, might believe that we

are in the final stages of our historical development, but that seems like a

distant future for many others. Across the globe, many people spend their lives

in extreme poverty, or wear military fatigues and engage in guerrilla warfare

in the mountains or desert.

For them, contemporary life remains a

back-breaking, nightmarish ordeal, no different from life in the eighteenth or

nineteenth century during the so-called ‘age of modernity’. For some people,

time flies at the speed of light, while for others, time sluggishly slinks

along at a snail’s pace, continually pausing to look back. People’s burning

desire to move faster and their fear of getting left behind continues to

produce more and more divergent times within the present. All these differing

time trajectories overlap and interweave in complex ways to form the world of

the ‘here and now’.

Our

daily lives are as fragile as a cracked wine glass, ready to shatter into

pieces at the slightest nudge. Nonetheless, even with horrific tragedies

happening all the time in different parts of the world, we continue to go about

our daily lives unfazed. We must repeat our daily routine—going to work or

school just like the day before, and the day before that—and pretend that we

cannot hear the screams and cries of pain beyond the wall.

Despite

such isolation, we dare to speak of contemporaneity because we are now able to

‘see’ the outside world with fascination. One of the most important tasks

assigned to photography since its inception has been to infiltrate and bring

back images from the other layers of our fractured world. For some people, the

world is bright, warm, and brilliant, but others live in a world of suffocating

darkness. The bravest and boldest photographers—those with fire in their

blood—relentlessly break into others’ time and space, allowing us to ‘see’ into

their world. If it is possible for some of us to sacrifice a bit of our

peaceful lives in order to help those in distress, then it is possible for

photography—and photographers—to change the world.

Photographers

who strive to connect the severed layers of the world and who use their cameras

to help the weak oppose the mighty often develop a reputation of being rather

proud, or even arrogant. We eagerly consume the legends of these heroic

photographers and the tales of their fiery passion that the media delivers.

Certainly, they do sometimes risk their lives, and they are often quite

deserving of our praise and enthusiasm. And some of their photos have indeed

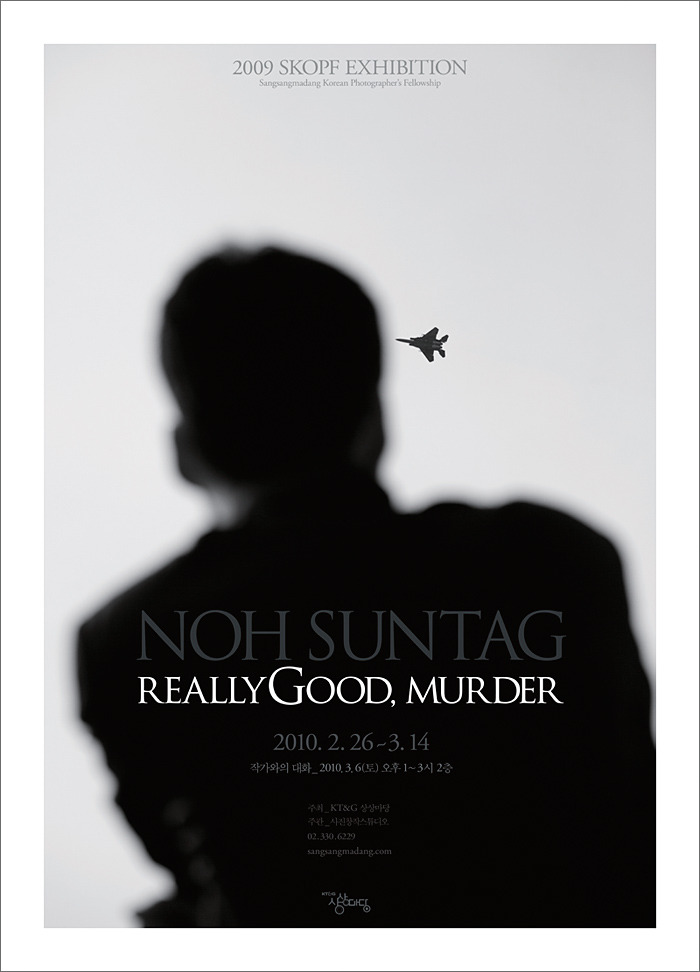

changed the world. The subject of this article—Noh Suntag—can certainly be

included among these fiery photographers. But despite the fact that Noh spends

his life on the run, striving to stay ahead of the pack, he cannot help

incessantly doubting himself and his photography.

2.

Noh Suntag (b. 1971) is the rare photographer who began his career as a

journalist before transitioning to become an artist, whose ‘artworks’ can now

be seen in renowned international museums and art biennales. Fate certainly had

a hand in this, but that is not something he could have controlled.

About

two years ago, one critic wrote that Noh ‘signifies the pinnacle of what Korean

photography can achieve in its history’. Almost immediately thereafter,

however, he took him off this pedestal in an article written just two months

later. Looking back at that particular article, the words are quite lofty and

verbose:

“The

words of Jesus are the best source for contemplating the meaning of faith over

the last 2000 years. Faith is the truth of one’s wishes, and the proof of what

one cannot see. People often hope that their faith might lead them home, but

many have died by following their belief. They may not receive the promise of

their faith in this life, but they will find their home in heaven. Therefore,

those with faith can never lose their way….People like Noh Suntag, however, who

do not have faith and who constantly doubt, can never find their home. By

trying to be both activist and artist, Noh will continue to be tormented,

unable to give up either the political or the photographic. While some have

crowned him as a “social-minded artist,” others point their finger and accuse

him of using political images to sell his “art.” While some hands elevate him

to artistic greatness, others throw him down to the ground. Noh Suntag is

doomed to wander, never to find serenity. But of course, he is simply reaping

what he himself has sown.”

As

often the case with weak-minded critics, he must have given in to the reckless

desire to capture the artist through his own grandiloquence. But now, two years

later, nothing has changed, and it is time to pick up where those words left

off. As seen in the photos of this exhibition, Noh remains as tenacious as ever

in his photography. The world is still dark, with the sun hidden behind the

clouds. Water drops from water cannons spread and sparkle like snowflakes, as

Noh Suntag still takes his photos at a full sprint. The flashlight of his

camera sporadically penetrates the darkness, uncovering people with bizarre

expressions, who seem to be laughing and crying at the same time. When he

elaborately arranges his photos on the walls of the museum, he seems to be

categorizing specimens.

Nonetheless,

despite the occasional trivial victory as an artist, Noh’s career as an

activist has been marked by a seemingly endless series of setbacks. His front

has been pushed back further and further, as Noh and his colleagues have been

defeated in Maehyang-ri, Daechu-ri, Yongsan, and Gangjeong. In both politics

and photography, the world two years ago is not much different from the world

today. Perhaps that is why my vocabulary for discussing his work also has not

changed. Can we truly make any progress? I have my doubts, but I will write as

if my life depends on it.

3.

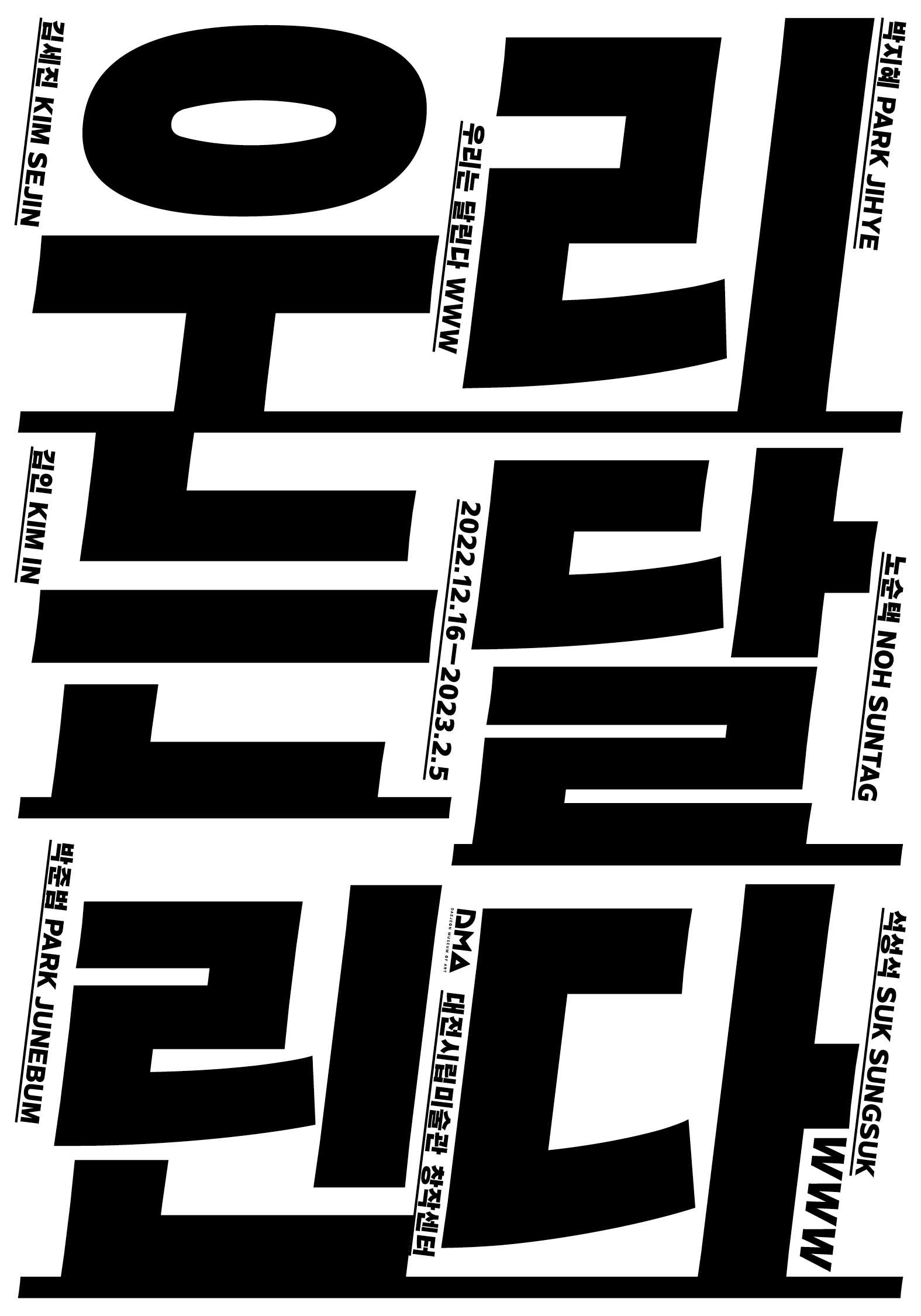

For this exhibition, Noh Suntag presents photos of people taking photos. His

subjects come from various walks of life: Noh’s fellow photojournalists on the

spot covering various news events; police taking photos of protesters as

evidence; people taking commemorative photos; elderly people taking “selfies”;

children playfully snapping pictures of someone lying in the street. The title

of the series is Sneaky Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence,

hinting at the vast difference between the actual moment of taking a photo and

the final image in the frame. For every ‘decisive moment’ that the audience

passively observes within their comfortable surroundings, the photographer must

peer through the lens while contorting his or her body into various awkward

positions, extending an arm or lifting a leg.

More

than any other photographer, Noh Suntag excels at extracting certain moments

from the flow of time, so that we may perceive their inherent distortion and

grotesqueness. One of Noh’s predecessors with a similar knack for capturing the

bizarre moments hidden within everyday life in capitalist society was Martin

Parr, who delivered unforgettable imagery by artfully distorting scenes of

tourists taking photos in front of famous sites, such as the Leaning Tower of

Pisa or the Parthenon.

The photos of Sneaky Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence

may lack the instant gratification of Parr’s works, but that is because they

cover a much wider span of time and space. Noh’s series consists of disparate

shots taken throughout his career at many different sites and events. As such,

they defy easy categorization with an obvious theme, and they lack the

consistent aesthetic style of his other series (e.g., the strAnge

ball, State of Emergency, and ReallyGood, Murder). However, what

they lack in lucidity and concision is more than made up for by their expansive

range and depth, which provoke more profound and rewarding reactions in the

viewer.

Originally

created for the series entitled Bird Guide,

these photos represent the longest lasting works of Noh Suntag. Notably, he has

re-titled the photos for this exhibition, but what is he trying to imply with

this new title? Does he mean that the people taking the photos must crawl into

every nook and cranny, with the flexibility and stealth of a snake? What can he

possibly mean by conjuring images of serpentine people taking photos of one

another? I cannot say for sure, and people with a lot on their minds are sure

to reach different conclusions that are hard to communicate or comprehend. At

any rate, I have never known another photographer who is constantly agonized

over the act of photography as much as Noh Suntag. In order to better understand

his work, we must first backtrack a little bit.

From

the beginning of his career, Noh has been deeply concerned with investigating

the act of photography. His ‘official’ career as a full-fledged artist began in

the summer of 2004, when he presented an exhibition and book, both

entitled Smells like the Division of Korean peninsula.

His debut was not exactly a sensation, as the photos of this series were a

motley mix. While Noh’s unique aesthetics and distinctive black humor were

present in some of the photos, others remained stuck in the straightforward

framing of media photography. The series of Smells like the

Division of Korean peninsula certainly contains the DNA of

the artist: political themes, a unique aesthetic sense, an obsession with

ethics, and a working method of a photojournalist. All of these elements would

be further developed to later reveal Noh Suntag the ‘artist’ who we would come

to know in the future.

Noh

Suntag had quit working as a photojournalist about three years prior to Smells

like the Division of Korean peninsula, but the works of that

series still look like those of a media photographer. The photos convey an

intense criticism of reality, an obsession to understand the historical context

of contemporary social phenomena, and a tenacious desire to expose social contradictions

and enact social participation. Already, however, Noh seemed to feel a strange

sense of incompatibility with his photography. Some doubts began to emerge

within the photos, like the larva of Ammophila sabulosa

infesta, a wasp that grows inside the body of a host. It was as

if the photographer himself was openly questioning his own efforts: ‘There’s

something awry with these photos. Can I really believe what I photographed?’

Then

and now, Noh’s working method has always worked like a photojournalist. When

taking his photos, he probably stands alongside other photojournalists without

feeling out of place. Like all photojournalists, Noh ventures into areas where

the social fabric is being torn by explosive problems and conflicts. The

fingers that press the shutter on his camera are often trembling with rage. His

photos are sent to the world directly from the night time streets of Seoul,

where protests are being violently suppressed; from Daechu-ri, Pyeongtaek,

where the residents were forcibly relocated due to the U.S. military; and from

Gangjeong village, Jeju Province, where a gray-haired priest is forced to

defend himself against combat police. Through Noh’s photos, we come to know

what happened in these places; as such, his works fulfill a fundamental

function of photojournalism.

However,

Noh Suntag is unique as a photographer who constantly doubts the things that he

photographs. He delves deeper into his subjects, even beyond doubt, to ask

whether the viewers truly believe what he photographs. The distance between the

fiery events captured by photojournalism and the cold doubts of photography is

much further than we think. Constantly maintaining such incompatibilities

within one mind and body must be extremely painful and difficult.

In

fact, the identities of a ‘photojournalist’ and an ‘art photographer’ are quite

different. Believing in the power of the camera, photojournalists are

constantly rushing into the world of others without hesitation. But the dynamic

photos of these fire-blooded photographers cannot immediately be considered as

artworks. In the realm of art, only a real conservative still believes that

photography is capable of directly representing the objective ‘truth’. Unlike

photojournalists, art photographers are continually contemplating the

limitations of the medium of photography. In other words, they inherently doubt

the type of truth produced by photography. Thus, it is only by doubting his own

photos and forcing the viewers to consider them more deeply that Noh Suntag the

photojournalist becomes Noh Suntag the artist.

For two or three years after Smells like the division of

Korean peninsula, Noh Suntag constantly spewed out photos, like

the wild and violent spray of an unmanned fire hose. He produced vast quantities

of work, including series such as Bird Guide and National Flag

User Guide, and numerous other works that cannot be neatly tied

together as one series. Moreover, it was during this period that Noh took many

of the primary photos from several of his finest series, including The

strAnge ball, State of Emergency, and Red House. All

of these works ambiguously hover around the boundary between art photography

and photojournalism.

Both The

strAnge ball and State of Emergency focus

on the unfortunate events that occurred in Daechu-ri, Pyeongtaek in 2005 and

2006. Following the prolonged negotiations between Korea and the United States,

and ratification by the Korean National Assembly, some U.S. military bases were

relocated to Daechu-ri. The residents who had lived in Daechu-ri for

generations were evicted from their homes and farms overnight. Most of the

residents were farmers who knew no other way of life, so they intensely

resisted the seizure of their land. But they could do little to oppose the

Ministry of Defense, which automatically dispensed compensation for the land

through the court system and then put up wire fences around the seized

properties.

The government came in with forklifts to uproot crops and throw the

residents out. When the farmers resisted by tying bands around their heads,

standing in lines to guard their land, they were labeled as ‘seditious’ to

society due to their ‘frontal attack on governmental authority’. Since the

Korean War, many of the residents’ had arduously struggled to create tiny

patches of farmland by painstakingly digging out the flats, hauling and

spreading fresh dirt, and removing the salt with their own hands. Through their

long struggles, they had finally succeeded in turning the tidal flats into

rich, arable land, so it was little surprise that they fought tooth and nail to

hold onto it.

But

their tiny, isolated resistance proved futile against the massive united front

of the military and police. On May 4 and 5, 2006, soldiers and police swarmed

into Daechu-ri and arrested 600 people. Unbelievably, to combat a handful of

farmers armed with bamboo sticks, the government sent a fighting force that

included more than ten Blackhawk helicopters. Hired mercenaries and a battalion

of engineers attacked and demolished the village with forklifts and bulldozers.

Ironically, May 5th is National Children’s Day in Korea. While children in

other parts of the country were gleefully smiling with presents, children in

Daechu-ri watched helplessly as their fathers and uncles were brutally beaten.

Such is the separation that divides our world. A month later, the whole

incident was forgotten as our nation turned its eyes to the World Cup in

Germany, enthusiastically cheering on the ‘Red Devils’ for the Korean team at

the top of our lungs.

How

would Noh Suntag choose to photograph this type of environment? If he was a

straightforward documentary photographer, he would have taken photos of the

abhorrent violence of the state, the impotent rage of the righteous farmers,

and the tear-filled eyes and shocked expressions of the innocent mothers and

children. Then we could have fully indulged in our anger, and perhaps shed

tears of our own over the photos.

Of course, such straightforward documentary photos have always been part of

Noh’s oeuvre. They were included in his past works, his present works, and will

continue to be included in the future. However, most of the photos from The

strAnge ball and State of Emergency do not evoke our

empathy. They almost seem to be freeze-frames taken from the most bizarre scene

of the darkest comedy. Images of explicit violence or tragedy rarely appear. In

fact, it is not even clear who is the assailant and who is the victim.

Looking

at these photos, we would have no idea what really happened in Daechu-ri. All

we could see is grotesque, bleak scenery. In The strAnge ball,

a round radar tower silently watches us from a distance, like the

moon. In State of Emergency, combat police

glitter and shine in the light, like a swarm of crustaceans. The farmers

besieged and knocked down by the police look so distinct that the whole thing

seems to have been theatrically staged.

For The

strAnge ball, Noh Suntag took a ‘roundabout’ way. Hovering

across the land, he took photos of the quiet countryside of Daechu-ri, always

sure to include the ubiquitous ‘Radome’ (radar + dome) of the U.S. military.

The resulting images are a distinctive mix of traditional Asian ink wash

paintings, with a theatrical touch. With his wife and young daughter, Noh

falsely registered as a resident in Daechu-ri and opened up a photo studio

there.

As a social activist, Noh takes portraits of the elderly to be used as

their funeral photo, and as a journalist, he trembles with rage while pounding

out sentences filled with incendiary curses and criticism. Strangely though,

once he gets a camera in his hands, he prefers a more ‘roundabout’ attitude.

With his characteristic self-deprecating manner, he grumbles, ‘this is not the

time to whine about the ball in Daechu-ri’. He makes excuses for his

‘roundabout’ way, saying, ‘The story of my photos begins with the white ball,

but I hope it finds its way to the farmers of Daechu-ri, who had lived a tough

life under the white ball’.

Maybe

Noh Suntag felt distressed. Although these photos resemble conventional

documentary photos, they are clearly meant to function in a completely

different way. Documentary photographers are typically guided by two

fundamental beliefs: that it is possible to capture the ‘truth’ through

photographs, and that photographs have the power to inspire people to act. By

carrying out these beliefs in reality, documentary photographers are practicing

their own brand of ethics. They seek to invade the complacent minds of people

who are comfortably ensconced in the narrow layers of their everyday lives. The

ultimate ethical goal of such photographers is to arouse our anger by forcing

us to look beyond our own peaceful lives and to unite against the disconnection

of the world.

However,

Noh Suntag’s ethics are much more complex and entangled, because they revolve

in two different orbits. Like most photojournalists, he is ethically driven to

document incendiary actions and events so that they can be seen by more people.

Guided by these ethics, Noh routinely rushes to various sites and takes his

camera directly into the conflict and the mud-flinging. At the same time,

however, Noh feels the ethics of an artist who incessantly doubts his own

actions and questions the limitations of photography as a medium.

Can

photography record reality of life? Isn’t photography just another tool and

excuse for remaining oblivious, causing us to remember only those fragmented

scenes we see in captured photograph? Is it really possible to understand

others’ lives simply by viewing photographs from our own safe perch? In truth,

don’t people just want to be emotionally moved by images? Can you really

believe what you see in a photograph?

These

doubts are hopeless. Yet, they have not been resolved, and they never will be.

It is this critical mind for probing the limitations of photography that makes

Noh Suntag an artist, but that mind is constantly at odds with Noh Suntag the

photojournalist. Indeed, it is this complex and even vicious ethical compulsion

that makes Noh’s works so captivating. Overall, the work of artists who are

driven by some ethical compulsion is generally more interesting than that of

artists with no such compulsion. This distinction goes beyond ‘boring’

explanations such as the social responsibility of art or the artist’s duty to

engage with society; it can be attributed more to the simple fact that the

works of artists with an ethical compulsion are usually much more peculiar.

Ethics

have a very powerful effect on works of art. If artists are completely immersed

in some ethical pursuit, their works tend to be rather boring and fragmentary.

But those artists who are driven in multiple directions by conflictive ethical

compulsions, who refuse to give up on any of their beliefs, often create works

that are bizarrely and often beautifully distorted.

The

beauty in Noh Suntag’s photographs comes from such conflicted ethics. Despite

the fact that he is addicted to photography, he simultaneously thinks that

photography should not be believed. Accordingly, he tries to keep people from

carelessly empathizing with his photos. Thus, he subverts the aesthetic

sensibility of conventional documentary photography, which emphasizes our

universal humanity and relies upon our ability to empathize with people whose

lives are very different from our own. Of course, Noh does not want his

photographs to serve as mere propaganda, subjugated to political and ethical

purposes. After all, as an artist, he must continually produce new aesthetics

and beauty.

Perhaps this is why Noh’s photographs of highly combustible sites have a beauty

that can only be described as chilling. As the gravitational pull of his social

ethics becomes stronger, he must overcompensate towards beauty in order to

avoid being dragged along. For example, Noh’s photographs from the

series, Namildang Design Olympic, which were

taken at the actual site of a crisis where people’s lives were being threatened

right before his eyes, have a desperate beauty, which is not present in

his Oh Bu Ba series with images of parents

and children. At the same time, however, the photos of Namildang

Design Olympic are much more inconsistent. While some of

them resonate with a transcendent, ominous beauty, others fail to escape the

gravitational pull and are thus no more than ordinary journalistic photographs.

With

his keen eye and sharp framing, Noh captures moments that reveal the awkward

and ludicrous bare face of the state, with its violence and contradiction. This

unsightly face is bared not only in news media, but also in museums. Repeatedly

murmuring the same questions, the artist Noh Suntag finds himself on an endless

treadmill. By now, every photographer is familiar with the writings of Susan

Sontag and John Berger, so they must certainly reflect on whether photography

is indeed ethical. But Noh seems particularly obsessed over this quandary. Most

photographers are able to reach a prompt conclusion with regard to the ethics

of photography. They either give up photography altogether, or become an

“artist” who freely experiments with aesthetics and the limitations of the

medium, and finally some become a documentary photographer who prioritizes the

need to inform the world of suffering.

Once

you have truly suffered from something, you cannot suffer from it again. Of

course, throughout your life, your thoughts might return to the heated problems

and questions that made you suffer, but they have already been settled. A minor

fever at an early age serves as immunity against more serious fevers in the

future. But Noh Suntag seems unable to get past his suffering. He seems to be

in a constant state of fever as he takes his photographs. He is in a perpetual

state of hesitation, hovering around the sites and shuttling back and forth

between art photographer and documentary photographer. In the midst of such

deep-rooted fever, the clichéd criticisms of documentary photography—‘If your

photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough’—are merely empty

words.

As

mentioned above, I once wrote that Noh Suntag represents the pinnacle of what

Korean photography can achieve in its history, and I still believe this to be

true. There has never been a photographer like Noh Suntag, and there will never

be another one like him. Indeed, who would ever want to burden themselves with

the weight of his problems and predicaments? I also wrote that he was doomed to

wander and hover forever. In truth, anyone who refuses to surrender to

deception must wander. After so long, why would he now suddenly pretend to be

fooled by photography?

4.

Returning to Sneaky Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence,

we must consider the strangeness of the photographers who appear in Noh’s

photographs. Unlike the typical portrayal in the media, these photographers are

neither aesthetic nor heroic. They are often captured in ridiculous poses as

they maneuver for the best angle for their photograph. Of course, they

immediately strike the viewer as possible self-portraits of Noh Suntag, so

looking at them might make people feel a bit melancholy. The grain of these

works is quite different from that of Noh’s other works. Previously, Noh has

gone to great lengths to remind us that he is just on the other side of the

framed image, that he is not an impartial recorder, and that even photographs

documenting actual sites can lie and distort reality.

On the other hand,

in Sneaky Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence, he objectively presents

scenes of the moment when a photograph is produced, and forces us to

contemplate the strangeness of such moments. While his previous ‘roundabout’

works chart the limitations of photography through political scenes, these

photos describe photography directly, as if to encourage us to recognize the

inherent flaws with his previous on-site photographs. He is reminiscent of a

restaurant owner specializing in the Korean dish ‘sun-dae’ (pig

intestines stuffed with various ingredients), who eagerly grabs a disinterested

person and tries to give the gritty details of how the dish is made. It is as

if he wants to say, ‘Now that you know how it is made, can you still savor it?’

As such, the series seems to provide further evidence of Noh’s habitual doubt.

By

continuing to photograph even while openly doubting photography, Noh is

demonstrating the severity of his addiction to photography. Examining his

photo-essay Fur, I began to think that maybe

this doubt is what he likes most about photography. How fickle and capricious

photography is—but that’s what makes it so captivating! If he weren’t so drawn

to the doubt itself, then why would he continue to feverishly take photographs

and write like an addict?

For

an artist and photographer, one advantage of such an addiction is the sheer

amount of work one can produce. In photography, of course, it takes tremendous

effort and diligence to produce the huge number of shots needed to capture a

single moment of transcendence. While Noh’s photography operates very

differently from conventional photojournalism, he still benefits from the quick

hands and relentless work ethic of a photojournalist, which are rare qualities

in the art world.

Thus,

Noh will never become exhausted. So long as our disconnected and alienated

world continues to squeak with explosive bursts of social conflicts, Noh Suntag

will be able to run through the streets in hot pursuit. He will stay true to

his belief that he and his camera must wander due to the reality of the

division of the two Koreas, and he will continue to produce his bizarre but

beautiful photographs.

He

is not the type of person who can easily change. For example, in the preface of

his catalogue Oh Bu Ba (2013), he wrote

‘How strange it is, in Korea in the spring of 2013, to idly take photos of kids

whining for piggyback rides even as the fog of the nuclear war lingers in the

air’. He used almost the same wording in the preface for The

strAnge ball (2006), and this sentiment can be traced

further back to the worldview of Smells like the Division of

Korean peninsula (2004). In this belief, he remains as

stubborn as an ox, which sets him apart from the majority of Koreans who once

shared his feelings about the ‘reality of the division’ but now speak more

positively about ‘neoliberalism and globalization’ or the ‘structural

contradiction of capitalism’.

With

his stubborn consistency, the artist Noh Suntag will not be easily depleted.

Even if Korea were to be reunified, North and South Korea would quickly become

homogenized, and there would still be many world issues in need of our

attention. Now that the digital network allows photography to be distributed

and consumed at a lightning speed, both belief and disbelief seem to be

stronger than ever. All of this is ample material for the art of Noh Suntag.

The

question is, will the addict Noh be satisfied with such issues, or will he

continue to develop an increased tolerance, causing him to require more potent

stimuli? Could he ever really feel content taking the same type of photographs,

still rushing to the scenes with his gray hair? It seems somewhat ironic that

artists’ works usually change over time, because our thoughts and minds do not

change as much. Looking back, Noh’s photography has actually changed quite a

bit. In the wake of his series ReallyGood, Murder (quick

and sharp snapshots) and The Forgetting Machine (his unquestionable

masterpiece), he is not as playful as he once was. The tones and colors of his

photography have become lighter, and the dark humor of The

strAnge ball and State of Emergency are

nowhere to be seen. His most recent photography looks much more morose than

ever before.

Sneaky

Snakes in Scenes of Incompetence may be a card that he kept

up in his sleeves for a long time. But how many more cards does he have left?

After directly exposing the strange and uncanny nature of the act of taking

photographs, what is left for him to show us? Of course, Noh will not stop so

easily. Like any great card player will tell you, the real game begins when you

have no good cards left in your hand. Likewise, real travel begins when you

have nowhere left to go, and true addiction starts when you could not possibly

be any more addicted.

Originally,

I thought I would conclude this article by sharply rebuffing those

critics—myself included—who have commanded Noh to continuously advance in terms

of both form and content. Such things are easy for critics to suggest, but is

there really such thing as continuous advancement? Does any critic really

believe that such a thing is even possible? Critics simply love to point to

some ephemeral examples, like the Russian avant-garde, as evidence of such

moment, and then assume a haughty attitude in front of the artists.

But

in the course of writing, I changed my mind. If the artist himself wants it

this way, who I am to suggest otherwise? Noh himself is clearly addicted to

advancing the form and content of photography. So I say that we stragglers, who

quietly put down our cameras after reading Susan Sontag, should just silently

watch the ridiculous yet sorrowful back of the suffering artist, Noh Suntag.