Main image of "Sculptural Impulse" at the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. June 9, 2022 - August 15, 2022. ©Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA)

Main image of "Sculptural Impulse" at the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. June 9, 2022 - August 15, 2022. ©Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA)The younger generation of artists subverts boundaries, blends existing ideas, and creates something new and original from the conventional. As contemporary art continues to change by fusing with different genres, many young artists have taken sculpture to a new level, adding new perspectives to the genre, especially as the boundaries between reality and virtuality continue to blur.

The Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) in Nowon-Gu, Seoul, has gathered seventeen young artists between the ages of 20 and 40 who have reinterpreted the sculpture genre from a new angle.

Sculptural Impulse is an exhibition that examines how these young and emerging artists understand contemporary sculpture; attempt to solve issues surrounding the sculpture; and add new perspectives to the ever-changing genre.

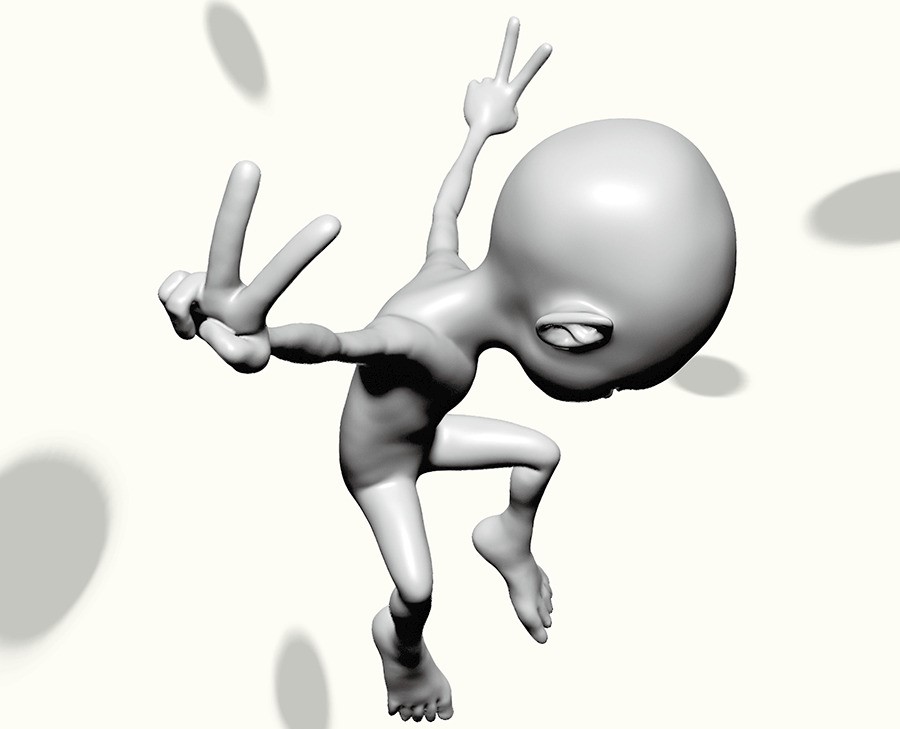

Front: Moon Isaac, 'A' Show must go on: After the Gate,' 2022, Mixed media ['A' series (2017), 'Viewport' series (2016-2017), 'Bone-Flesh-Skin' (2018), 'Bust #6' (2022)], 350x215x120cm.

Front: Moon Isaac, 'A' Show must go on: After the Gate,' 2022, Mixed media ['A' series (2017), 'Viewport' series (2016-2017), 'Bone-Flesh-Skin' (2018), 'Bust #6' (2022)], 350x215x120cm.Back: Kwak Intan, 'childsculptor,' 2022, Resin, PLA, acrylic, water paint, epoxy, urethane foam, steel, aluminum mesh, 374x176x142cm. Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Photo by Aproject Company.

The large gate-like work of Moon Isac greets visitors at the entrance. Inspired by Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, Moon’s works allow you to travel through space and time. The different sides of the gate represent the entrances to hell, heaven, and somewhere in between, allowing visitors to appreciate the various landscapes of the exhibition space.

Numerous public sculptures remain on the streets, their original intent and function long forgotten. To create a new monument, Jihyun Jung re-created a commonplace street statue out of meshed aluminum sheets.

Jaewon Kang’s S_crop resembles a massive iron sculpture that has penetrated the ceiling of the gallery. The work, which was created using a 3D program, can be easily transformed and relocated in virtual space. Taking this into the real world, the artwork is transformed into an inflatable that can be deflated into a 2D form. Thus, the work transitions from 3D to 2D and from virtual to physical space.

Kwak Intan’s four sculptural works consider the fundamental meaning of sculpture. Similar to how young children freely explore and create, he combines various iconographies from art history, images from contemporary society, and portions of his previous works to create something new.

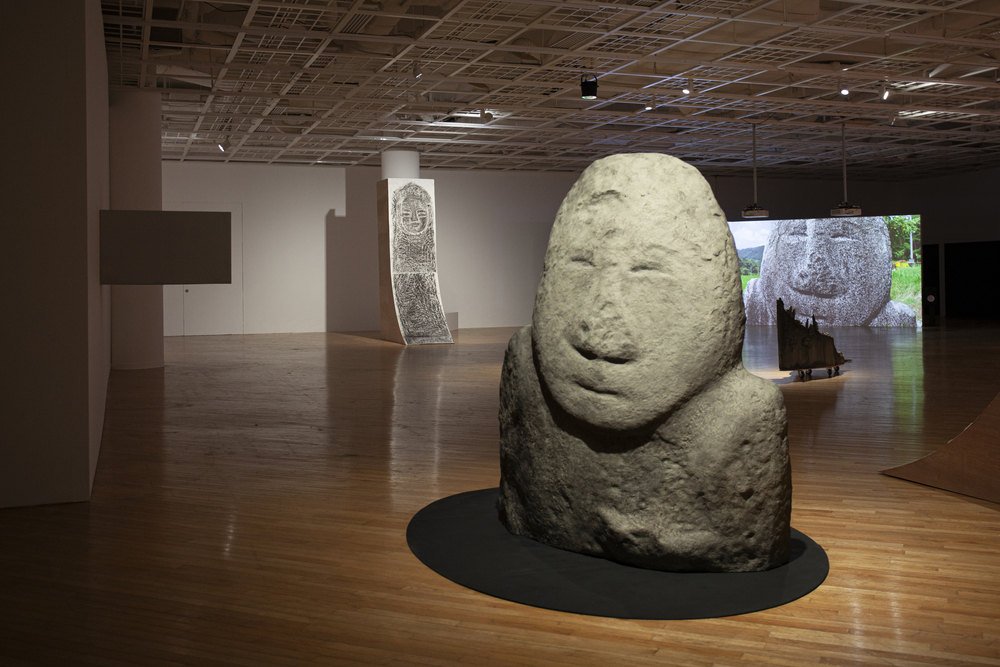

Oh Jeisung, 'Index_Chojeon-ri Maitreya,' 2020-2022, Ceramic, wood, PLA, inkjet print, 220x300x200cm. Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Photo by Aproject Company.

Oh Jeisung, 'Index_Chojeon-ri Maitreya,' 2020-2022, Ceramic, wood, PLA, inkjet print, 220x300x200cm. Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Photo by Aproject Company.Oh Jeisung discovers unspecified cultural assets found in various regions in South Korea. After photographing a Maitreya Buddha sculpture in Gimhae, Oh uses a 3D scanner to create a mold modeled after the small statue and then experiments with the process of re-creating the statue. Oh experiments with the genre through the use of various techniques that have never been seen in traditional sculpture.

With a 3D pen, Yejun Hong uses Gore-Tex material, which is lightweight and functional. He draws lines repeatedly and sharply, which eventually become a stack. The artist observes the trajectory that occurs during the creation of these lightweight sculptures, as well as the moment when production is delayed. The artist also collects digitally-created optical illusion elements and expresses them as sculptures.

Goyoson’s work is set as a stage where visitors can participate and become one of the sculptures. The artist created sculptures of boots, a bus stop, and a fountain, as well as statues of singers, leaders, and lovers. The artist infuses the statues with hippie values and a belief in love to defy the existing social system.

Hanna Woo’s fabric sculptures are reinterpretations of bodily organs that can be worn as clothing. It was created to represent the artist’s emotions and sensations while undergoing surgery. Participants can imagine different bodily experiences, such as undergoing surgery, having gills, or having a womb.

Choi Haneyl, 'Acute indigestion: totalizing,' 2022, MDF, color board, sponge, fomex, acrylic board, steel, styrofoam, Dimension variable. 'Digest: dematerializing, Datefication,' 2022, Cement, 180x35x18cm. Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul Photo by Aproject Company.

Choi Haneyl, 'Acute indigestion: totalizing,' 2022, MDF, color board, sponge, fomex, acrylic board, steel, styrofoam, Dimension variable. 'Digest: dematerializing, Datefication,' 2022, Cement, 180x35x18cm. Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul Photo by Aproject Company.In a single exhibition space, the two works by Choi Haneyl face each other. As technology advances, Choi contemplates new materials and physical properties of sculpture and describes the current state of the sculpture genre. Choi compares this situation to an “imoogi,” a large serpent that attempts to transform into a dragon. The fact that the dragon is only visible through the QR code indicates that the sculpture is no longer material.

Rhee Donghoon’s works capture the most iconic K-pop dances. Rhee intentionally overlaps different poses in the sculpture and uses chainsaws and chisels to express the fast movements of the dance. The artist, who majored in painting, attempts to create sculpture-like paintings and paintings-like sculptures. Rhee focuses particularly on capturing the visual senses of contemporary media in sculpture.

Five enormous torsos of women wearing identical hairnets are facing the wall. Faces and hair are drawn with graphite and colored pencils on the surface of these colossal sculptures made from French fry bags and paper boxes. Shin Min depicted female workers, the majority of whom are employed in high-stress, low-paying positions. The artist hopes that her works will reveal discrimination and hatred against female workers, as well as inspire solidarity among them.

Hwang Sueyon is an artist who creates “paper bodies.” The three massive works in the exhibition, like robot-building toys, can fit together as if they were body parts. Hwang uses the human body scale as a standard, creating hollow “paper body” pieces that subvert the concept of traditional sculpture.

Don Sunpil created a maze-like pedestal and placed statues that resemble collectible figurines. Following the pedestals, the images of these figurines become interconnected. Don attempts to show his works as outcomes of mass production or Internet image distribution.

The framework of Choi Taehoon’s artwork consists of IKEA furniture with inflated urethane foam on top. Based on Choi’s discretion, ready-made items lose their original functions and exist as such, independent of their functionalized form.

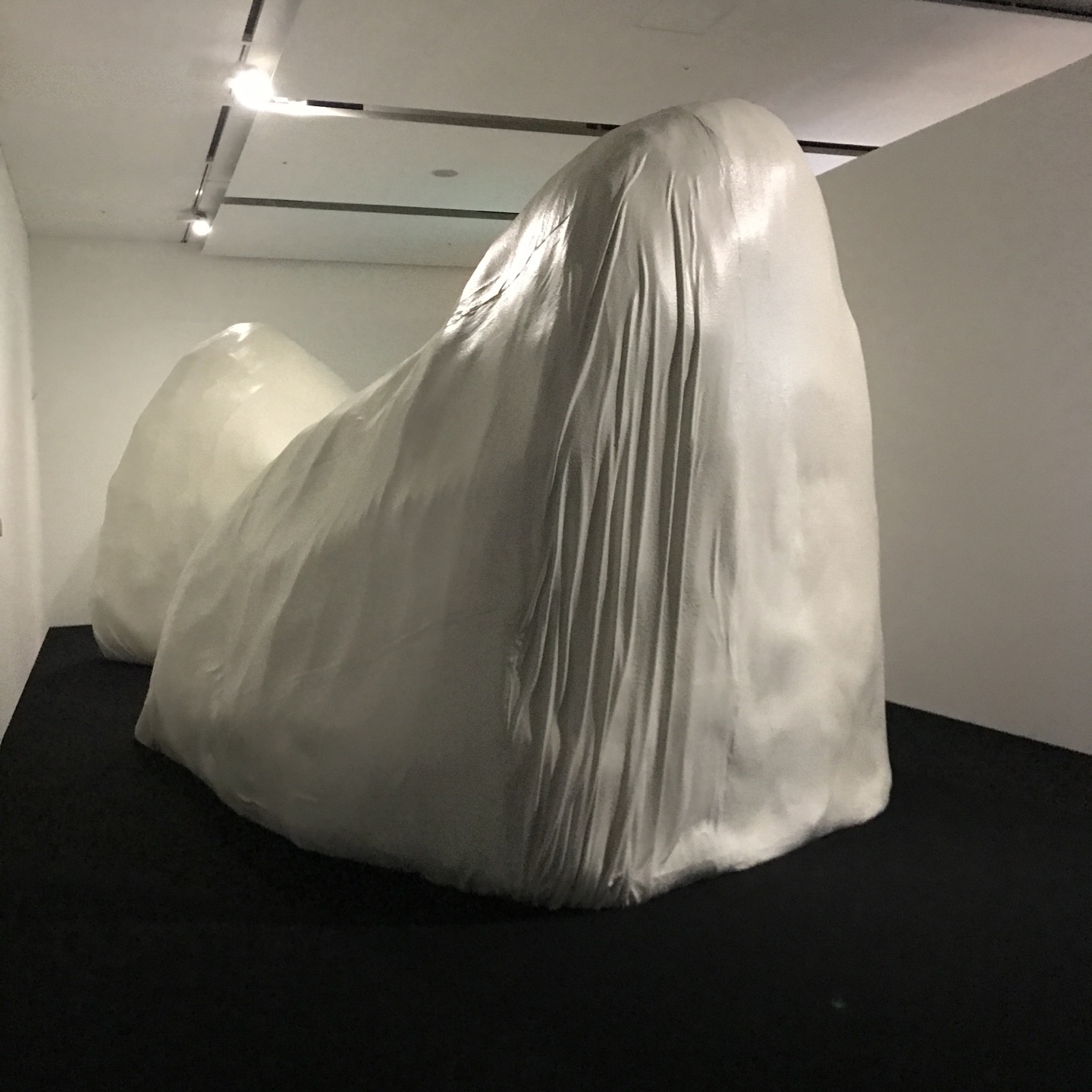

Juree Kim, 'Wet Matter_202206,' 2022, Wet soil,, mixed media, scent, 290x400x300cm (2ea). Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Photo by Aproject Company.

Juree Kim, 'Wet Matter_202206,' 2022, Wet soil,, mixed media, scent, 290x400x300cm (2ea). Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul. Photo by Aproject Company.Juree Kim’s “Wet Matter” series is made of clay that retains its shape when wet. The series was inspired by the Yalu River Wetlands in Dandong, China, a region on the border with North Korea where various cultures are exchanged. The artwork, which is an artifact as if it were natural and matter itself as if it were a form, is intended to reflect the circle of life and death and the temporary moment in between.

Choi Goen created marble sculptures based on the shapes of common household appliances such as pressure cookers, air fryers, and computer monitors. The artist removes the lower portion of the sculptures and places them on a pedestal as tall as a person. Choi attempts to draw attention to the social issues surrounding mass production by presenting these objects as aesthetic works that provide a chance to reflect on the industrial system.

Kim Chaelin’s sculptures are works that viewers can directly touch, experience, and appreciate with their bodies. The artist’s work falls somewhere between art and everyday items. The artist experiments with the relationship between the sculpture and the audience, studying how viewers interpret the work with their bodies.

Sculptural Impulse is on view through August 15, 2022, at Buk-Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA).