An art museum’s collection reflects the values of its contemporary society. The collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) is a manifestation of the institution’s core values and their adaptation to the shifting tides of society.

MMCA Cheongju Art Storage Center. Photo by Aproject Company.

MMCA Cheongju Art Storage Center. Photo by Aproject Company.In the post-modern era, national museums were built to consolidate the state or ruling class. The first museums built in Korea during the Japanese colonial period were part of a colonial policy, while those built during the Yushin regime served a community that fostered nationalism.

Today, museums no longer collect and exhibit works that highlight a culture’s glorious history; instead, they seek to collect works that embody more inclusive and pluralistic values, such as encompassing the stories of those who have been overlooked throughout the course of art history and revealing historically repressed traumas.

As such, the ideologies and values reflected by museums have evolved over time, and their collections, which are frequently the most visible expression of an institution’s identity, reflect these changes. Therefore, museum collections are closely tied to the ideological situation of the time.

The collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) also illustrates the evolution of the museum’s values as they have adapted to the different historical contexts in which the artworks were collected.

The MMCA’s collection history in this article is based on Yeon Gyu-seok’s paper, “A Study of Globalization, Characteristics and Nationality in MMCA Collection from 1971 to 2020,” which describes the collection’s evolution over time.

From 1971 to 1980

MMCA Cheongju Art Storage Center. Photo by Aproject Company.

MMCA Cheongju Art Storage Center. Photo by Aproject Company.The MMCA opened its doors in 1969 at Gyeongbokgung Palace. However, it wasn’t until 1973, when the museum moved to Deoksugung Palace, that it began to collect artworks. During this period, the MMCA shifted its focus to actively collecting artworks for permanent exhibitions and enhancing public recognition of modern and contemporary art as a cultural heritage.

The works collected between 1971 and 1980 were intended to establish the history of Korean art. From the late 1950s to the 1960s, during the political and social upheaval following the Korean War, the Korean art world experimented with various forms of artistic expression while simultaneously expanding its awareness of international art through international biennials.

It was during this period that Dansaekhwa painting emerged in the Korean contemporary art world, coinciding with the prevalence of the Art Informel movement in the local art scene.

In 1975, Tokyo Gallery hosted a group exhibition entitled Five Korean Artists, Five Kinds of White, which was the first show in Japan dedicated to the works of contemporary Korean artists. This exhibition first discussed the monochromatic white color, which has been acknowledged as the origin of the Korean Dansaekhwa and has driven the discourse of a unique Korean contemporary art movement. Other art movements, such as the new figurative Korean painting and Korean photorealism, emerged during this period.

However, the number of works in the museum’s collection at this time was only 396, and the museum acquired an average of about 40 works per year during this time period. The majority of the collected artworks were modern Korean paintings, including traditional Korean-style and Western-style paintings, as well as modernist genres such as abstract painting, Art Informel, and Dansaekwha paintings. Only two works by international artists were collected by the museum during this period.

The artists whose works entered the collection at that time were Kim Eunho (1892–1979), Noh Su-Hyeon (1899–1978), Park Sookeun (1914–1965), Go Hui-dong (1886–1965), Nam Kwan (1911–1990), Park Seo-Bo (b. 1931), Chang DooKun (1918~2015), Heo Geon (1907–1987), Suh Se-ok (1929–2020), Yoo Youngkuk (1916–2002), Seund Ja Rhee (1918–2009), Whanki Kim (1913–1974), Heo Baek-Ryeon (1891–1977), and Quac Insik (1919–1988).

From 1981 to 1990

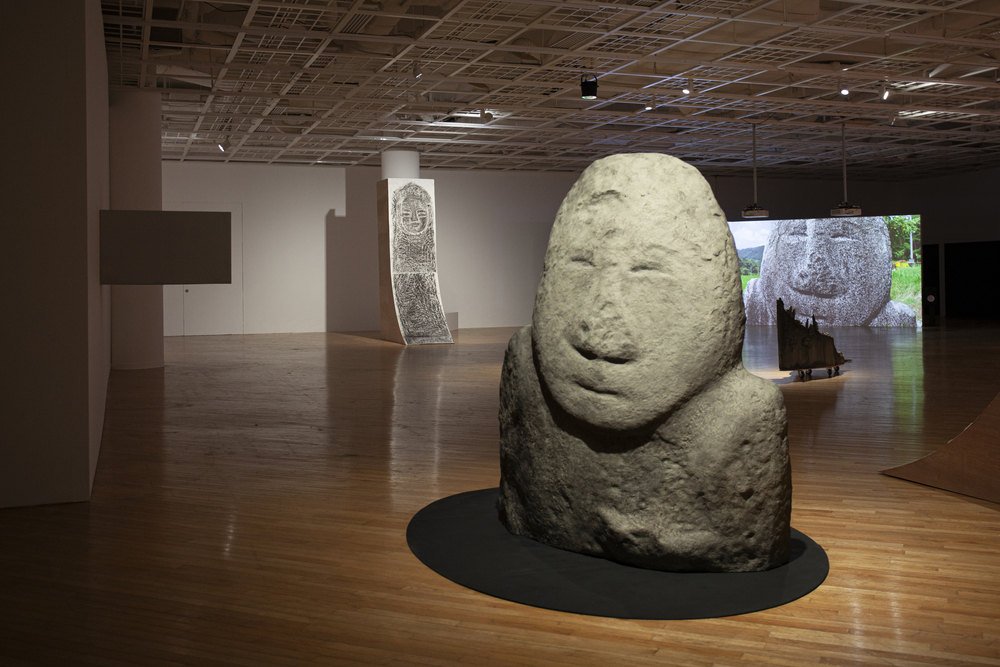

Exhibition view of “To the World Through Art Highlights of MMCA Global Art Collection from the 1980s–1990s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). Courtesy of the museum.

Exhibition view of “To the World Through Art Highlights of MMCA Global Art Collection from the 1980s–1990s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). Courtesy of the museum.

The 1980s witnessed significant national and international changes in the art world. As the influence of post-modern culture spread in the 1970s, the international art world began to confront previously marginalized, discriminated against, and taboo subjects, such as women, homosexuality, immigrants, the physically disabled, drug addiction, and pornography. With the rise of photorealism, graffiti art emerged in the U.S., while Neo-Fauvism and Figuration Libre gained prominence in Europe. These artistic movements gained widespread recognition and found their way into the collections of art museums.

In the 1980s, South Korea experienced rapid economic development and a growing middle class, which led to a significant expansion of the country’s cultural and artistic scene. First and foremost, South Korea has been striving to maximize its capabilities in all areas as it hosted the massive international events of the ’86 Asian Games and the ’88 Seoul Olympics.

The MMCA also underwent significant changes during this period. In 1981, in accordance with the policy of the Ministry of Culture and Public Affairs, Lee Kyung Sung, an art critic, took over as the museum’s director. This appointment marked a pivotal moment, as Lee became the first art expert to hold the position. Moreover, in 1986, the MMCA opened the Gwacheon branch, which led to organizational growth.

During this period, funding for collections also increased. Prior to 1986, the average budget of $100 million had increased tenfold. In addition, the number of collections in the 1980s reached a total of 2,819 works by various artists, showing a sevenfold increase compared to the 1970s.

In 1986, the museum introduced a work review system to increase the professionalism and public visibility of its collections. Many artworks by national art competition winners were added to the museum’s collection, and several donations were made during this period. Notably, 87 works by world-renowned artists, which were exhibited at the International Contemporary Art Exhibition commemorating the 1988 Seoul Olympics, were donated to the museum.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, the 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). Courtesy of the museum.

Exhibition view of “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, the 1960s-1970s,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA). Courtesy of the museum.At the time of his appointment as museum director, Lee Kyung Sung sought to collect works by young artists with high artistic potential. During this time, the MMCA collected works by modern artists similar to those of the 1970s, as well as works by younger artists who explored Korean realism and Korean artists active in the international art scene, including Lee Ufan and Nam June Paik. In addition, more works by female artists such as Bang Hai Ja (1937–2022), Chun Kyung-ja (1924–2015), and Wook-kyung Choi (1940–1985) were added to the museum’s collection compared to the previous years.

However, there was no collection of works from the Minjung art movement, which was active in Korea at the time. The exclusion of works from the Minjung art movement shows that the MMCA’s one-sided collection policy at the time did not adequately reflect the diversity and inclusivity of the art scene.

Nevertheless, in the 1980s, the museum’s collection became more professionally organized and expanded not only in quantity but also in quality. The museum focused on promoting international trends and the excellence of Korean culture and arts, including artists who were actively participating on the international art stage, as well as highlighting the contributions of female artists.