Like Beach–Studio, the work Love is

Real, hung against a neutral ground, is both the exhibition’s title

and a piece the artist himself describes as a successful work. Yet even in this

painting—whose ‘love’ and ‘real’ seem more affirmative than negative—the shadow

of cracking is cast. Love is Real, which is also a lyric

line from languid hippie music, depicts a flower-filled walking path. Though

neatly paved, the path does not seem to continue; it contains the unease of

spring, a season that demands something begin anew.

Foreshadowing that unease

are the tree shadows that split the pale ground like an abyss. The small path,

as if covered in untouched white snow, is segmented by lines that may have been

drawn unconsciously, but to the viewer they arrive as something more than mere

shadow. The fissures inside the work—which occupies half of the diagonal axis

cutting through the gallery—demand a certain hermeneutic imagination.

Especially because a dazzling work like Spring of Seoul, 1992

hangs nearby, the meaning of gaps and cracks becomes even stronger through the

contrast.

Of course, this work does not conceal that it is a reality assembled and

spliced together. Yet the urban view on the western side of the painting,

saturated with spring sunlight, unfolds as a scene of another dimension—beyond

simple representation or shabby everydayness—through swift and precise

placements of color planes carrying accurate information that make a scene a

scene. For the painter, such complete encounter and unity with this other

dimension may be what ‘real’ is, and what ‘love’ is.

Yet the frenzied hand that

seeks to capture that brief blessed moment of total fusion with the scene

cannot find firm ground on which to settle it. There may be many reasons, but

from an analytic standpoint it can first be attributed to the opacity of

painterly language. If conventional realism presupposes the transparency of

language, then Choi Gene Uk’s realism—just as he claims—is closer to the body

than to consciousness. Perhaps, moving forward, what may matter is the problem

of the flesh that has consciousness, beyond the mind/body binary.

In a book explaining post-structuralist theory, Catherine Belsey argues

that the hypothesis of modern linguistics, beginning with Saussure, maintains

that language is not transparent and is not a simple medium that delivers

messages about a world of independently constituted things. According to this

hypothesis, language is not an imitation of thought but the condition of

thought: it constitutes the world of individuals and objects and provides the

possibility of distinguishing them.

Terry Eagleton, in Criticism and

Ideology, adds a materialist interpretation to this

post-structuralist hypothesis, pointing out that without language there can be

no material production. Language is, above all, bodily and material reality and

thus becomes part of the material productive forces. Things cannot be thought

outside the system of differences that constitutes language. Signs detached

from referents and experience lead again to the separation of signifier and

signified. Language, as a system of differences, is itself made of gaps and

traces. It is not a single substance; reality is defined through difference

from other elements within the system, through cracks and blanks. In this

sense, the language Choi Gene Uk deploys is modern.

Ultimately, what the hypothesis of modern linguistics demonstrates is

that there is a gap between our direct experience and our use of (linguistic)

signifiers. When we speak or paint the world, the possibility of a direct

relationship between the self and experience is often damaged. The linguistic

concretization of experience is like scooping water with a basket full of

holes. As Eagleton notes, the artwork continually negates its own artificial

technique while trying to present itself as natural and clear, but this effort

always ends in frustration. In this way language obstructs the relationship

between the self and the world, yet it is also language that provides the

possibility of meaning.

At the same time, because language is not fixed and is

always in the process of change, texts are open to multiple interpretations.

Eagleton points out that the aesthetic integration of artworks is achieved not

on the myth of an organic community, but rather on the historical

self-divisions of bourgeois society. The more insistently the artist tracks the

real, the less firmly grounded reality becomes; it grows more unstable and

ambiguous. As in certain hypotheses of modern mathematics or physics,

uncertainty increases along with precision. Such is the case with Choi Gene

Uk’s paintings, which maintain representationality while continually trembling

and revealing an abyss.

In this exhibition, where even unfinished works were hung, he implies

that incompletion is as important as completion. What matters is the artwork’s

unconscious—an unconscious the work neither knows nor can know. As Freud points

out, the split gaps within a text are where interpretation runs rampant; and

although interpretation is a product of the ego, it is also heterogeneous to

the ego. Choi Gene Uk’s paintings reveal internal division, and that division

is the artwork’s unconscious. As modern philosophers emphasize, such division

foregrounds contingency over universality, diversity over unity, defect over

foundation, difference over identity. Michel Foucault, one of those thinkers,

describes the elements of knowledge not as a sum of information or a unified

mode of thought, but as a space of deviation, gaps, and dispersal, placing his

cultural model at the center of an active interplay of differences.

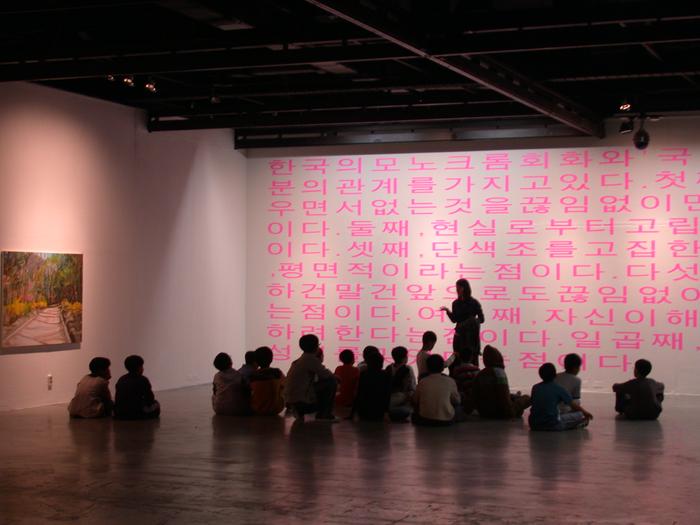

By fragmenting a homogeneous, single canvas—or by fragmenting

scenes—Choi Gene Uk emphasizes the textuality of the work: its character as a

net that has been broken or stitched together. Through this, the text produces

polyphonic sounds, a clash of multiple voices. The text is multilingual from

the start. The viewer, denied decorative and comfortable scenes, must, through

the work’s gaps, ‘seek the omissions the works present but cannot explain, and

above all, their contradictions’ (Catherine Belsey). Within its absences and in

the collision among diverging meanings, the text implicitly critiques its own

ideology. Illusionism that reassures and consoles the viewer is rejected, as

are narratives that conclude with a precise message of where something begins

and where it ends.

Catherine Belsey notes that the subject’s coherence and continuity

provide the conceptual framework of classical realism. The use of the

grammatical subject establishes the subject. But the ‘I’ of discourse is always

a stand-in, because no one can remain identically the same across different

moments. The continuity of the self is a myth. The subject is constituted

within language and discourse, and within discursive practice the symbolic

order is closely linked to ideology. Thus one may say that the subject is

constituted in ideology. Ideology hails concrete individuals as subjects, and

middle-class ideology in particular stresses a fixed identity of the

individual.

Unlike such middle-class self-sameness, the actual subject is

always in the process of ongoing formation. Because subjectivity is grounded in

difference, an imaginary unity with the world is delayed indefinitely. Belsey

further argues that the idea of the primacy of language over subjectivity was

refined through Lacan’s interpretation of Freud: Lacan’s theory of the subject

as constituted in language secures the decentering of personal consciousness,

and as a result the subject is no longer regarded as the source of meaning,

knowledge, and action.

The Lacanian subject is constituted on the basis of an irreversible

split. The ego of the mirror stage is alienation—that is, the moment of

distinction between the perceiving ‘I’ and the perceived (imaged) ‘I.’ For

example, in Choi Gene Uk’s Beach–Studio, the artist is

absent, yet appears like a ghost in the broken mirror; he seems to exist within

the left-hand picture that depicts a photograph, and also to exist within the

small painting inside the right panel. The artist is everywhere, yet nowhere possesses

a secure presence.

Through a situation of multiple prismatic refractions, he

paints the subject’s absence and division. The subject is continually defined

through other frames—whether painting or mirror—yet also slips away toward

somewhere else. Like the subject in the Lacanian sense, the text is an unfixed

process. However, in Choi Gene Uk’s case, while he is cool and—just as the

foregoing citations and arguments suggest—‘split’ regarding the problem of

painting, he has something clear to say about the real-world institutions

surrounding painting. This emerges in the works occupying the other half of the

exhibition’s diagonal axis, where the artist’s statements are more direct.

Today, painting may have entered a non-Euclidean dimension and, in the

thin air of that plateau, be producing high-level discourse about its meaning

and mode of existence; yet the world we live in clearly belongs to a

three-dimensional Euclidean reality. Even if contemporary

philosophy—post-structuralism or deconstruction—pursues rupture and

fragmentation of organic totality, this does not mean it collapses into

conservatism, as left critics have argued.

Terry Eagleton, in The

Function of Criticism, says that deconstruction is a liberalism

without a subject and thus, above all, becomes an ideological form suited to

late capitalist society: it thoroughly nullifies everything while leaving

everything as it is. Yet many post-structuralists were political activists. In

Choi Gene Uk’s work, however, the statements are not so much a politics of

division, or activism as an extension of division, as they are directed toward

something unmistakable. There is intention, a target of attack, and a certain

persuasiveness.