"I

wanted to make fake photographs that are extremely meaningless because I was

really irritated by words and theories surrounding art. I wished my photographs

to be meaningless, empty, and completely nonsensical."-

Kang Hong-Goo, "Drama set/Fragment/Disguise"

All

artists wish to get out of art history and the art system and make something

new that is not tied to existing customs. Practically all possibilities may

have been explored by their predecessors, however, and at this point when the

end of art history is being debated, attempts to make a change may seem

meaningless. However desperately one tries, it is difficult to get out of a

system that has already been solidified, and any effort to make a difference

usually falls into the evil cycle of reinforcing that very system.

Nevertheless, artists keep trying because the world they live in, constantly

changing through advancements in science and technology and with evolutions of

society, encourages them to continue their journey. Now photography, a modern

invention, not only is a widely accepted artistic medium in its own right but

also occupies an important place in contemporary visual culture. Only a few

years have passed since digital photography has been introduced. In that short

span of time, it has assumed the role of the main producer of visual imagery of

our era and has practically replaced our eye. Kang Hong-Goo has been making

digital photographs by manipulating popular cultural images with a scanner. His

art evinces that digital photography provides new opportunities for those

seeking a mode of expression that fits the time outside the art system.

Kang

enrolled himself in an art school as an aspiring painter after having spent

several years as an elementary school teacher. He initially majored in painting

but soon began to explore a new direction in manipulated photography utilizing

advertisement images and film stills. Kang states that the experimentation was

in protest against the art system that is based on a standard composed by

great, unique works. Kang, who calls himself a second-rate artist, not a

top-rate genius artist, has been making preposterous and bizarre fake

photographs with images appropriated from the mass media.

He deems the use of

preexisting images more suitable than a handmade painting in expressing one's

inability to resolve the conflicts of everyday life. His preferred display

format-prints simply tacked up on a wall-emphasizes the easy and instant nature

of computer-generated photography. In Kang's photography, the particular

condition of the high-speed modernization of Korean society is combined with

his personal experience of it. His photographs have unfolded in a series that

explores "location, snobbery, fakery"-the title of his second solo

exhibition.

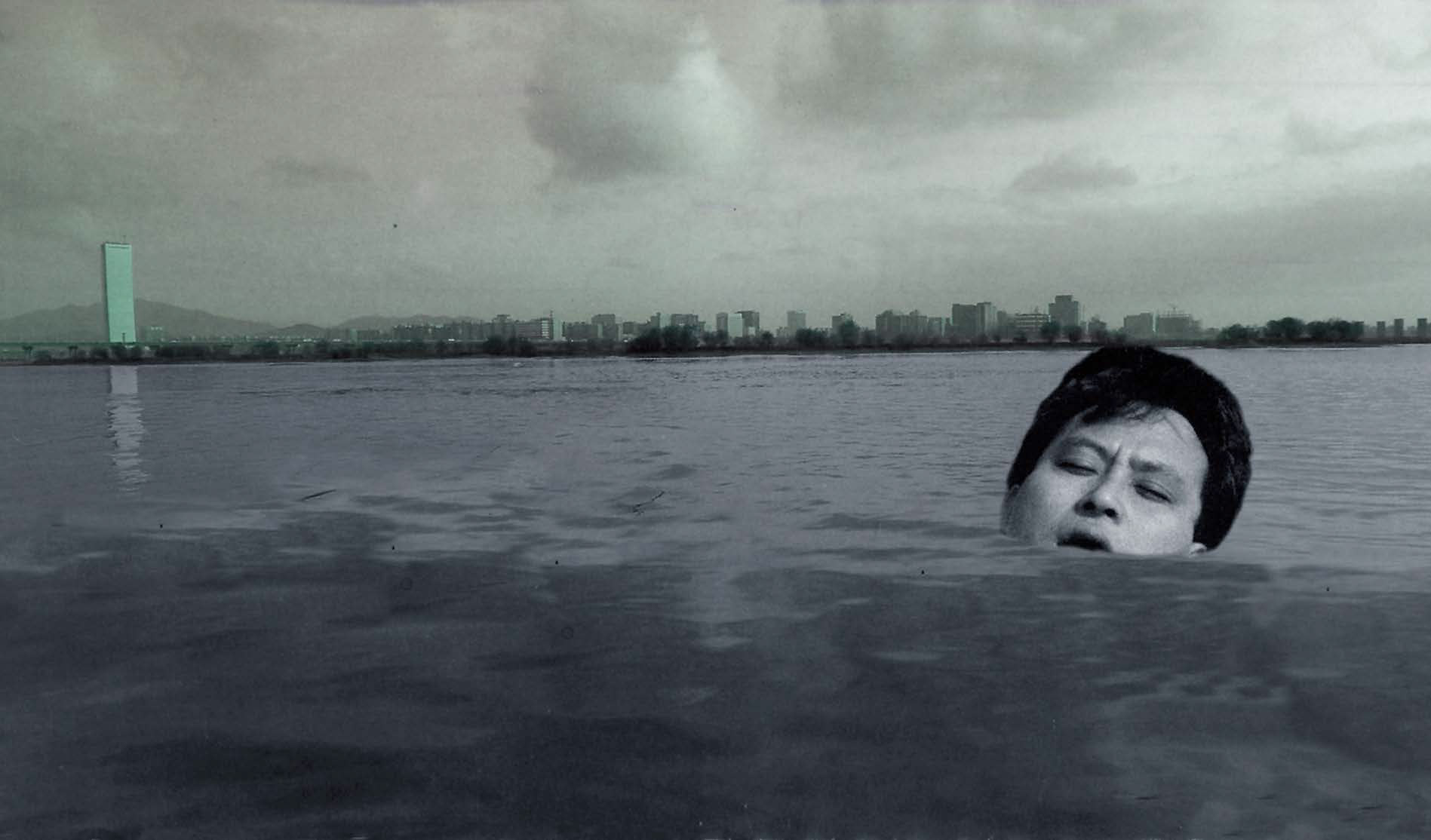

Kang's

early scanner-manipulated photography manifests the dis-eases and conflicts

lodged deeply in people's minds despite the economic prosperity that has

suddenly blossomed: surreal landscapes engulfed in fire (What Humans

Can Do for Trees), patriarchal homes haunted by monsters (Home

Sweet Home), and everyday scenes that reveal fears around the

condition of the country's division (Warphobia). In another

series of works, Kang casts himself as the protagonist in stills of fictional

films. As the main actor in movies of gratuitous violence and sex, the artist

creates dramas that mix narcissism and self-pity.

Art here is no longer a

serious and sublime medium but is made into a series of stock images one would

regularly see in cheap genre movies and commercial advertisements. In these

crudely manipulated photographic representations, the artist-the

director/actor-appearing in wonky guises turns despairs and disquietudes into a

comedy (Who Am I). These photographs, made with a deliberate

lack of refinement in order to divert the pressure to be creative, are

believable representations of our reality, which is far from refined and

polished in actuality. When Kang started using digital cameras, his

surrealistic montages gradually converged with the impressions of Korean

society the artist himself captured. This evolution arose from his belief that

the contradictions of reality are greater than the contradictions that he

creates.

When

the digital camera first became available, its small memory forced Kang to make

long panoramic landscapes by suturing many individual shots. These landscapes

do not attempt to be faithful representation of the reality through an

expansive, level gaze, however. They are recombinations of twisted impressions

of a society put together piecemeal. As the artist has stated, Korea has

leapfrogged from its pre-modern era to an era of information society in less

than a generation, and consequently all kinds of contradictions that reflect

the times and spaces that have been bypassed in the process clearly remain.

Kang's digital landscapes do not limn a future society ruled by a humankind

that has evolved through advancements in science and technology. Instead, they

are landscapes that harbor remnants from a process of modernization driven by a

fascistic military culture and collective egotism. It is not straight

photographic representation but manipulated montages of fragments that can

better and more precisely capture a reality distorted and perverted by

capitalism and commercialism in the midst of a compressed growth.