Dahoon

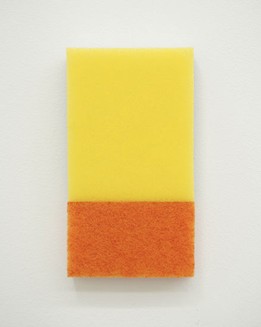

Nam’s practice begins by questioning the systems of value and structures of

reality that we tend to accept as given, using replication as his

core strategy. Rather than employing replication as simple imitation or

reproduction, he presents objects that closely resemble reality yet ultimately

reveal themselves as “fake,” exposing the fissures between the real and the

fake, the original and the copy, value and price. This line of inquiry extends

beyond the art system to encompass consumer culture, capital, desire, memory,

and the broader structures of contemporary society.

In his

early works, Nam began by replicating books he personally admired in

two-dimensional formats, gradually turning his attention to spaces and objects

from everyday life that are easily overlooked. In his solo exhibition 《#21》(Rund Gallery, 2019), he replicated a

laundromat located across from the gallery, while in 《#22》(oh!zemidong Gallery, 2020), he recreated a subway ticket gate.

These works operate by rendering familiar reality unfamiliar. Though the

replicated objects closely resemble their originals, their use of lightweight

and fragile materials situates them in a state that appears real yet is

unmistakably not.

In the

solo exhibition 《#23》(Gallery Yoho, 2021), Nam expanded this approach to encompass life

in the aftermath of the pandemic, weaving personal experience and contemporary

conditions into a spatial narrative framed as “traces of travel.” The

exhibition structure, reminiscent of a guesthouse, metaphorically evokes

memory, movement, and the instability of identity, signaling a shift in

replication from objects toward emotional and experiential dimensions.

In more

recent works, replication increasingly targets the structures of economic

systems and art institutions directly. The ‘MoMA from TEMU’ (2024) series and

the solo exhibition 《National

Junkyard of Modern and Contemporary Art》(ATELIER AKI,

2025) foreground issues of masterpieces, institutions, and authority, asking

how artistic value is produced and consumed. In this process, Nam does not

avoid the position of the “fake” as something negative; rather, he actively

embraces it as a site of subversive potential.