Let

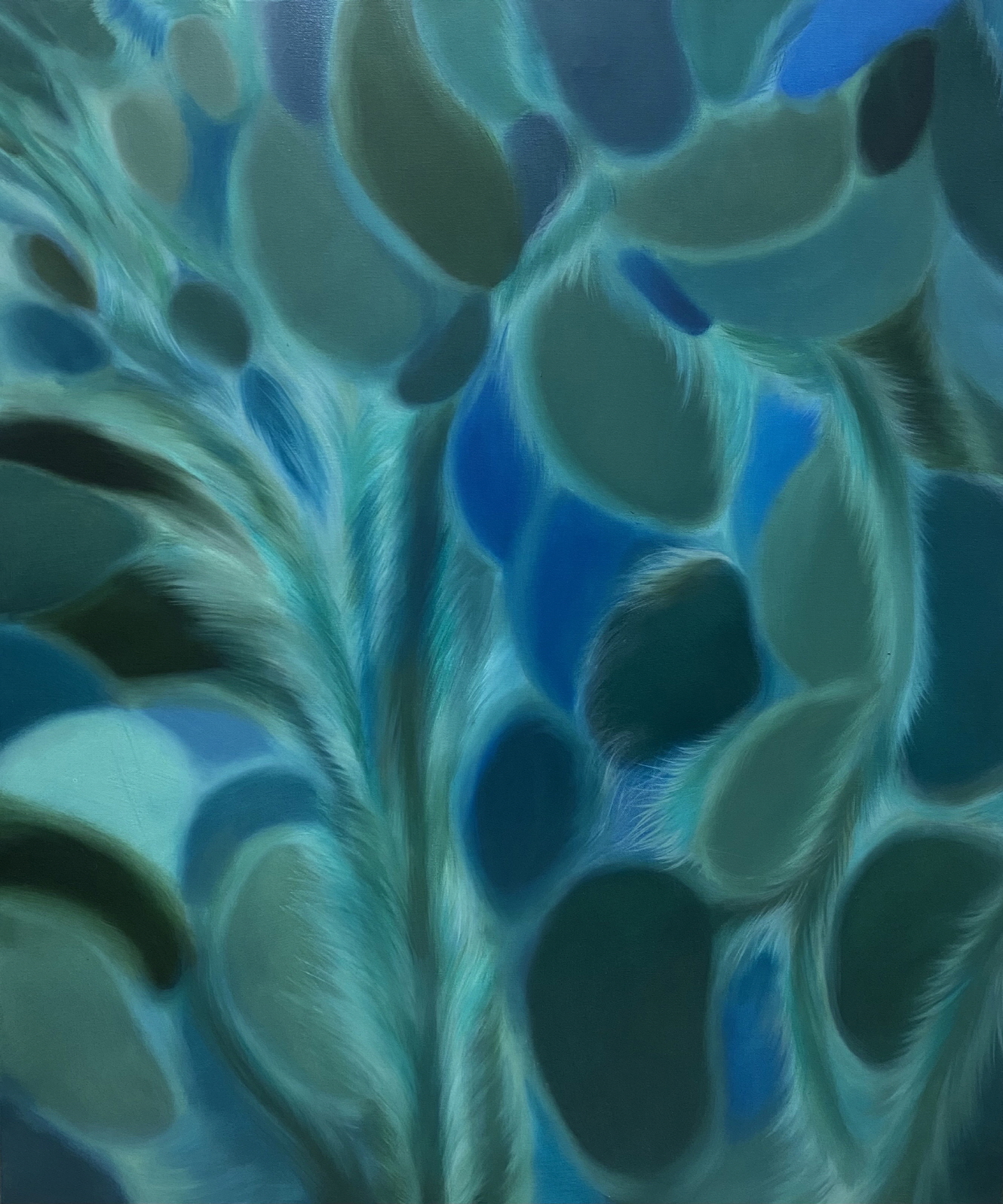

us return to the work. At some point, Kim became captivated by the strange

tactile qualities of alpine plants—their fur-like softness—and began painting

images where vegetal forms merged with animality. Until We Meet

Again (2025) is one such example. Though it is a flower, every

part of it—stamens, petals, stems, and leaves—is rendered with fine hair-like

lines, as is the surrounding environment of grass, trees, earth, and sky. By

translating the tactile sensations evoked by alpine flora into the act of

painting, Kim generates surfaces woven densely with linear textures.

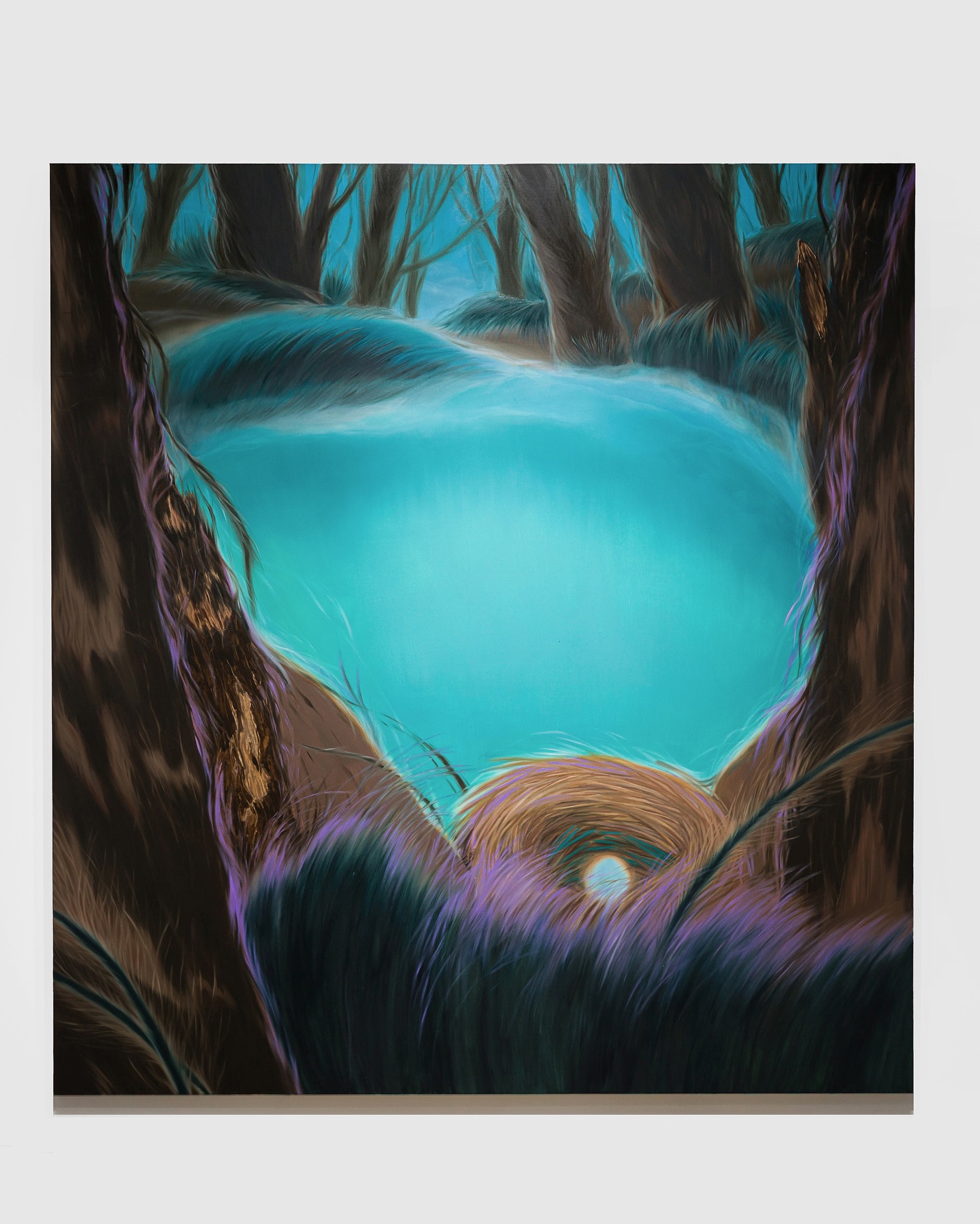

She soon

turned toward the themes of “forest” and “nest,” exploring the sensory

continuity shared by her repetitive, line-based drawing process (the body) and

the landscape she depicts (the subject). The direct catalyst for this shift was

the forest in Tongyeong permeated by her grandmother’s death—a place where Kim

witnessed the earth-toned darkness akin to the death of an animal and sensed

the presence of regeneration within it. The shadowy depths of the forest, the

primordial state of undifferentiated life, and the mysterious blue luminosity

that evokes the origins of all living things—these become the perceptual logic

of her imagination.

As

seen in The Bird Crying That Night (2025), Kim’s

interest in bowerbirds led her to bring birds directly into the forest of her

paintings—the very creatures that had provided conceptual grounding for the

sensorial density of her drawn lines. Beyond the bird’s abstract curves, she

focuses on the creature’s behavior: its repeated opening and closing of wings,

mimicking metamorphosis, and its gathering of discarded forest debris to build

a nest. This “nest-building” mediates life and death, death and life. For Kim,

the process becomes a perceptual entity that merges visual and tactile

sensation—a moment in which nest-building and painting become indistinguishable

acts.

Kim

notes that she has been “interested in the relationship between humans and

nonhumans, studying ways of understanding humanity through the modes of life

expressed by nonhuman beings.” She further explains that she explores the

“biosphere as a place where humans, plants, and minerals coexist without

essential differences, mutually dependent, where organic and inorganic entities

are blended.” Though the context differs, Cézanne’s approach to perception

offers a parallel: his painting proposed a fluidity between subject, object,

material, and sensation—not perception rooted solely in the human subject, but

a “process in which the subject empties itself and becomes the object.” (Jun

Youngbaek, Cézanne’s Apple, Hangil Art, 2008, p. 206.) The rhythmanalyst

that Lefebvre describes likewise integrates with the rhythms of the world.

Where

the Mountain Lives (2025) exemplifies Kim’s distinctive gaze

upon the forest. From the forest’s edge, the observer’s view moves toward its

depths—passing through the earth-toned darkness and the rough textures of dead

trees toward a world of soft, pliable linear forms. These forms align with her

brushwork, revealing a sensory transition that moves from the margins of the

canvas toward its center. It resembles the body of an animal, or perhaps the

silent signs rediscovered by medieval women who communed with the forest—those

whom others called witches.

Traversing

the extremes of macro (forest) and micro (nest), of the living (bird) and the

dead (branches), of darkness (brown) and light (blue), Kim seems to seek a

painterly gesture capable of overturning the binary roles of subject and

object. Much like the novelist who wanted to pronounce the word “forest” aloud

just to imagine the image it carried, Kim pursues a pre-linguistic form, a form

before form.

The

forest Greem Kim paints carries, in relation to such imagination, a kind of

memory—specifically, a memory of the body, and of the maternal body. It recalls

the womb as a primal space of isolation where life and death coexist, where

inside and outside are continuously connected, and where darkness and light,

vision and touch collapse into one field. Like weaving a textile, arranging the

dead vegetal lines with care, she produces a nest through actions that require

the same duration as a magical wingbeat—revealing the logic of sensation at the

heart of her work.

Building

a Different Kind of Nest (2025) naturally leads to the next

work. In the empty darkness of the forest—where she gives form to painterly

textures and volumes as sensory entities—Kim draws visual gaps onto the surface

of dead trees. Her metaphor of nest-building, the repeated and seemingly

indifferent act of laying down lines, expresses her faith in the sensory

possibilities that such repetition can produce. To “see” a painting, then, is

not enough; one must “sense” it. As returning to the forest would mean noticing

the bird’s movement or the crouching animal hidden within its shadows, sensing

a painting requires intimate entanglement between subject and object.

- Ahn

So-yeon (Art Critic)