Soomin

Shon’s practice begins at the fissures between personal experience and social

structure. Through the lenses of memory, language, and systems of belief, she

examines the hidden mechanisms that govern contemporary society and observes

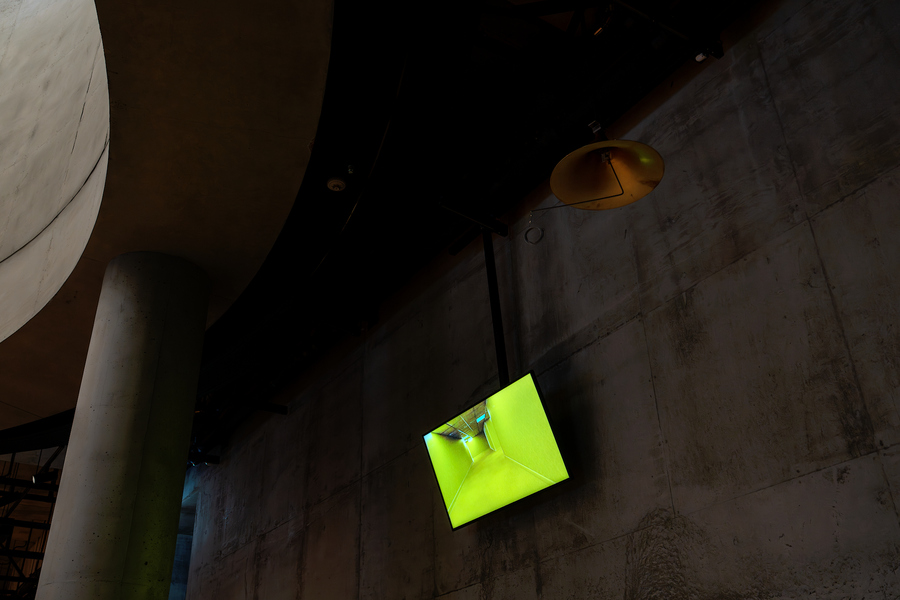

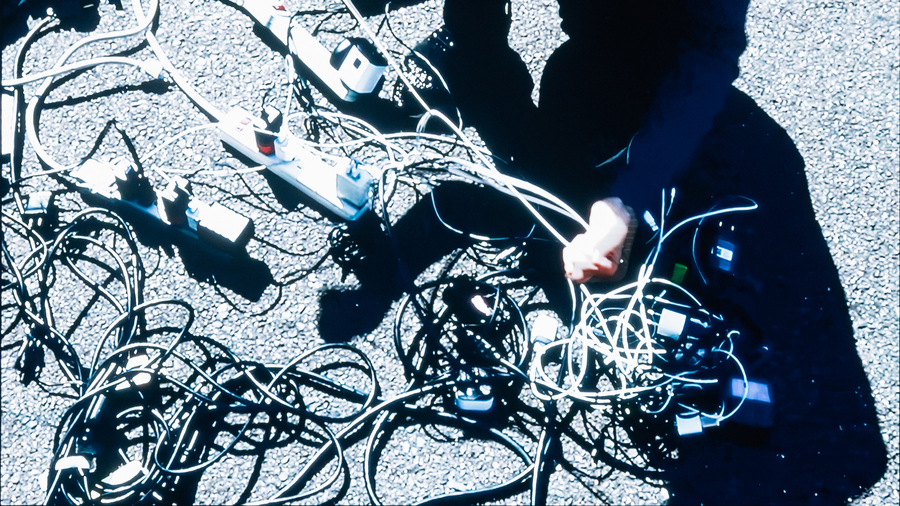

how they manifest as affect within everyday life. Her early work 3

Smartphones, 24 Phone Chargers and 4 Powercords(2018), based on an

image of Syrian refugees charging their phones, invites reflection on

unconscious prejudices toward “others.” By filming the process of reenacting

this photograph, the artist captures the emotional distance between ordinary

life and a tragic reality—an experience that marks the beginning of her

enduring inquiry into the relationship between self and other, reality and

representation, belief and lived experience.

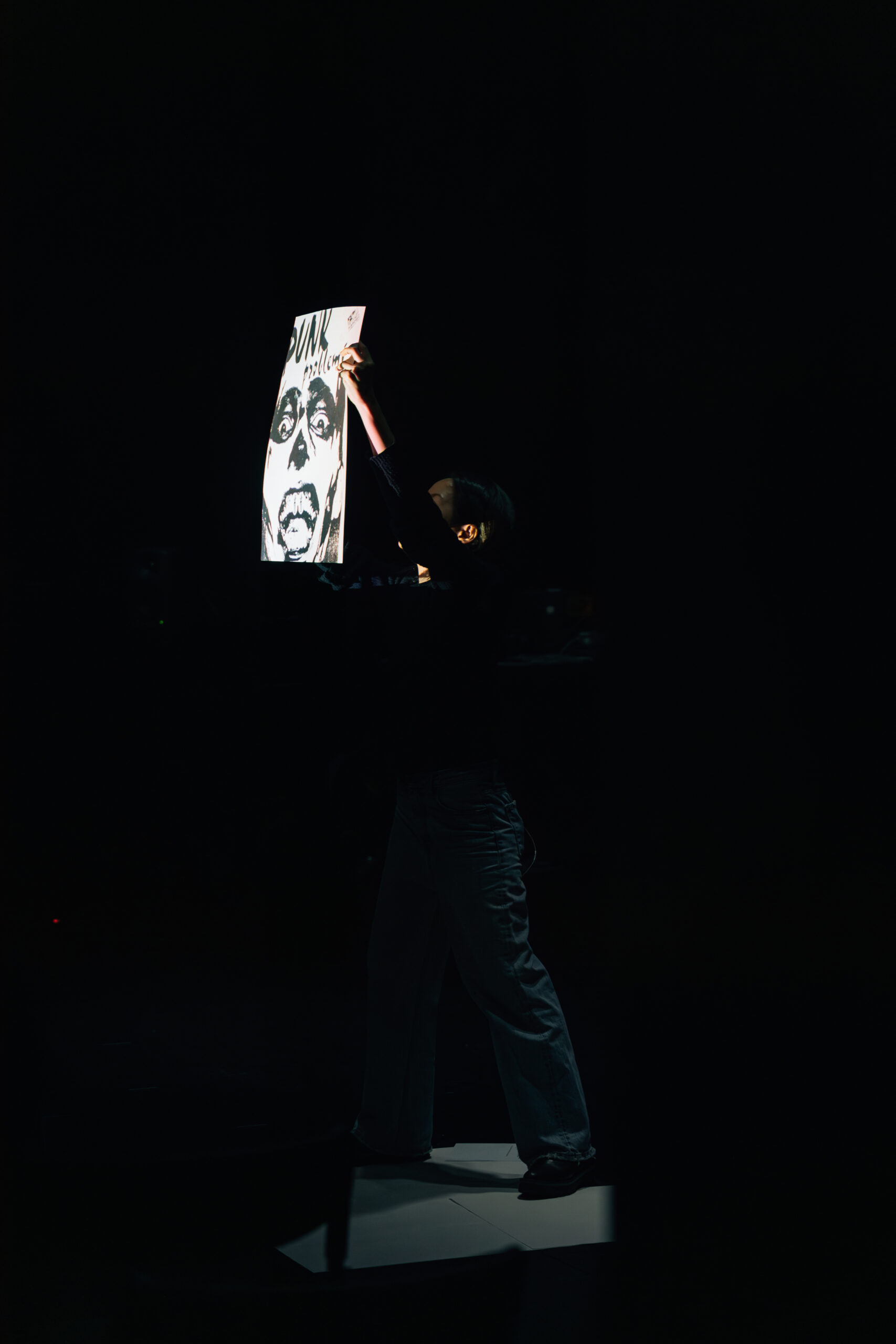

Unmellow

Yellow(2017–2025) emerges from her exploration of social relations.

Focusing on a yellow fire hydrant that everyone passed by without notice, Shon

questions the social implications of “not seeing” and indifference. She asked

multiple people to draw the object, later compiling the results into a book and

postcards, thereby revealing how a community constructs visual and emotional

distance. In the 2024 performance of the same title, she addressed the

impossibility of communication through language and moments of mistranslation,

declaring that “language creates the borders of the world” and linking

language, power, and otherness.

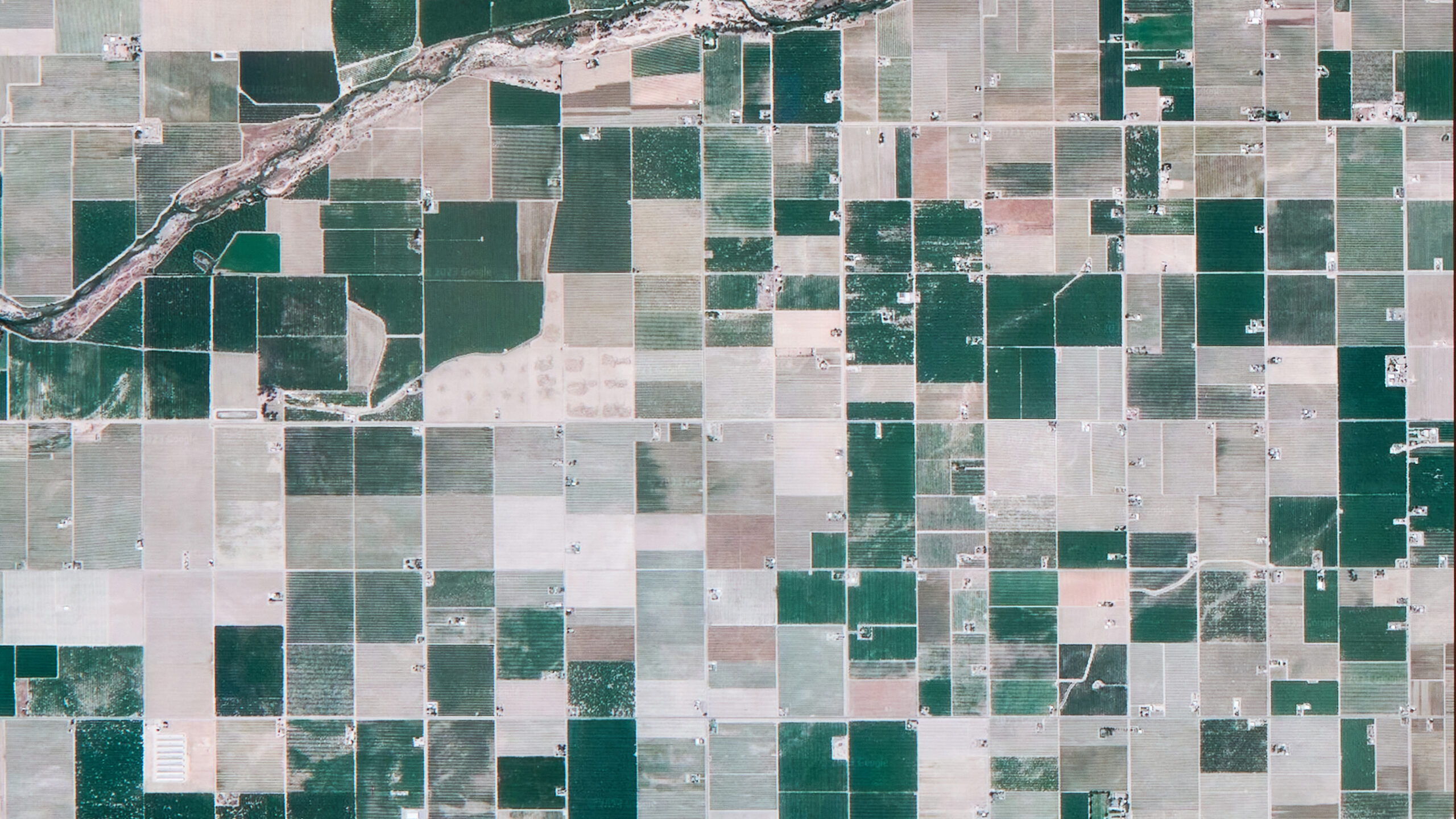

Shon also

delves into abstract structures such as belief, value, and order. In her solo

exhibition 《If Reality Is the Best

Metaphor》(SeMA Storage, 2023), she dealt with human

desire and loneliness that exist within the fractures of technological

capitalism, deconstructing the illusion of “trust” and “value” in In

God We Trust(2023). Starting from the phrase printed on the U.S.

dollar, the work expands its focus to cryptocurrency, financial crises, and the

origins of social faith, exposing how collective belief constructs reality—and

how that reality is always susceptible to collapse.

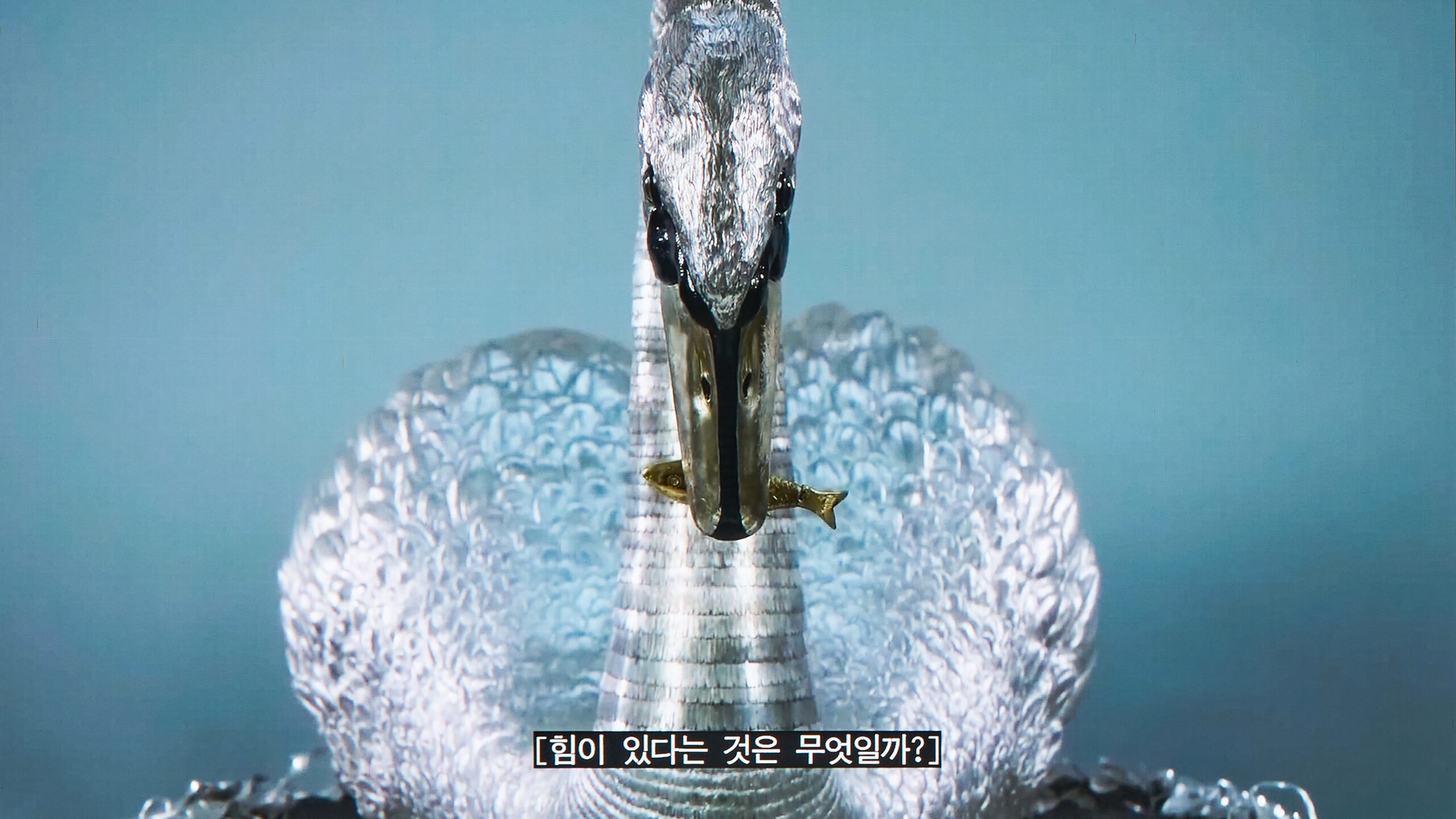

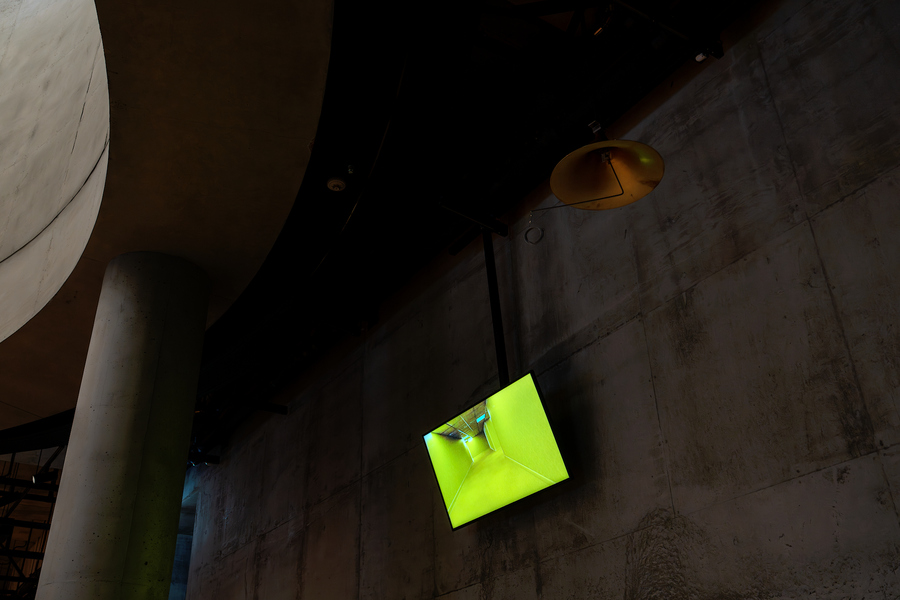

This

trajectory continues in her solo exhibition 《A Good Knight》(Hapjungjigu, 2023) with the

video A Good Knight(2023), which likens human society to the

rules of chess. Reflecting on individual position within systems of order and

hierarchy, Shon poses the question, “Are we the chess pieces, or are we the

ones playing the game?” Her attention to the “limits of movement” imposed by

social norms extends into Underground(2024), which explores

the meaning of humanity in an age of isolation and substitution shaped by

technological capitalism.