In

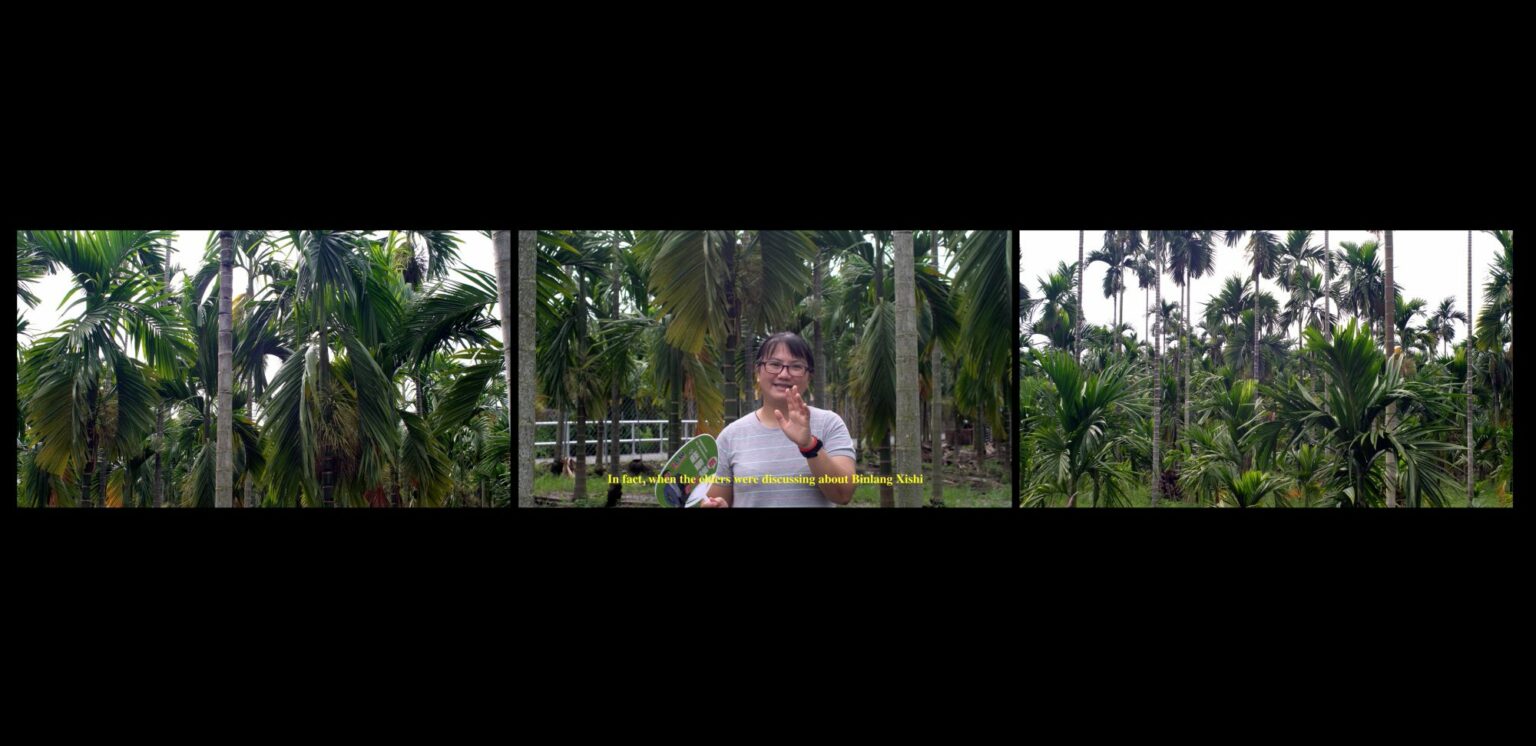

the film Missing (2024), which was made especially for the exhibition, Mooni Perry

engages in a reflective relationship with ideas of belonging in order to become

aware of a transformational moment that only arises from an external

perspective. Missing

contrasts a “longing

for the West”,

which is partly accompanied by a distorted, idealised notion of liberal

democracy and individual freedom, with a longing for the East. In response to

questions of authenticity and originality, which, in the context of hegemonic

historiography and the culture of memory, have become a weapon in the battle

for interpretive sovereignty, the film reacts with a snapshot that precisely

does not assume ‘true’ or ‘false’ narratives. Rather, the cinematic narrative

is itself an acknowledgement that the world is also viewed differently by

others and that an actual truth only manifests itself in the concurrence of

multiple perspectives.

The

title of the exhibition refers to a system of coordinates that the artist

mentally superimposes on the map: the x-axis ranging from west to east – from

Lake Baikal in present-day Russia, a region closely associated with shamanism,

to Heavenly Lake in the Changbai Mountains on the border between China and

North Korea; the y-axis travelling from north to south – from Manchuria, a

region that extends across the present-day borders of China, Russia and

Mongolia, to the Kailong Temple in Tainan, Taiwan. The temporal qualifier

‘present-day’ is essential in this respect, as these historical and cultural

landscapes have experienced a multitude of occupations and reinterpretations

during previous centuries, which have also resulted in the irretrievable loss

of East Asian cosmology and cultural techniques.

In

her research, Mooni Perry is particularly interested in the question of what

the idea of ‘East

Asia’ means

today, particularly in view of a history characterised by numerous ruptures,

and to what extent cultural, historical and philosophical traditions connect

China, Japan, North and South Korea, and Taiwan. There is an object in the

foyer of the Kunstverein that is also mentioned in the film: the

elaborately-decorated paper house on a wooden stool houses seven deities on

three floors. The Kailong Temple, located in Tainan, is dedicated to them. On 7

July, according to the lunar calendar, a rite of passage, i.e. a kind of

coming-of-age ceremony, is celebrated there: mothers accompany their (almost)

sixteen-year-old adolescents to the temple to receive a blessing for their

impending adulthood.

The

paper houses are then burnt, releasing the hope of being supported in the

future, which settles in the soot on the walls of the temple. The paper house is also

accompanied by a speculative narrative thread: already visible from the outside

through the glass façade, one can make out

larger-than-life figures on the wall. They represent members of the Asian

Feminist Studio for Art and Research, which Mooni Perry founded together with

Hanwen Zhang in 2020. This platform developed into a multivoiced network,

connecting people worldwide through weekly online meetings, in which ideas are

exchanged on the issues formulated there and also joint projects implemented,

such as this exhibition at the Kunstverein. The make-up and clothing of the

invented characters are based on the so-called ‘Ba-Zi’ of the members, which

means the ‘four pillars of fate’ in East Asian astrology.

When

Mooni Perry speaks of a “puzzle” when reflecting on concepts of

identity, this seems to be formally translated in the film Missing by the division into five

projection channels. The individual images, chapters or sequences sometimes

appear to be cobbled together in a disparate fashion, and yet the narrative

strategies and the juxtaposition of images in particular generate a world of

their own, albeit a singular one: individual scenes are dissected, so to speak,

when they are multiplied and shown from different perspectives. Connections

between different biographies and geographies are forged when five people

simultaneously look up at the sky in awe. Attention is drawn to a particular

dialogue when only one or two projections coincide. An individual life is

placed in a larger historico-political narrative when one of the protagonists

is seen on a bed in a hotel room whilst writing, with footage of the Chinese

border in Xiamen and the Taiwanese border in Kinmen placed next to her.

Missing

thus accompanies the viewer into a multitude of interstitial spaces that firmly

reject the opposing logical binaries of private/public, real/fictional,

outside/inside, religious/atheistic and, in particular, profit/loss, instead

allowing for unforeseeable correlations and contexts. This is also illustrated

by the improvised mode of direction, which, although a script and certain roles

were provided, ultimately gave the actors freedom to interpret and develop them

individually.

What

at first seems to be fragmented and far-flung coalesces in the final scene of

the film once more. The search for orientation sketched out in Missing, be it with the help of

an oracle, a fortune teller or prayers for love in a Chongqing temple, is

temporarily resolved in the get-together of AFSAR members in a Berlin

apartment, who celebrate their reunion over a meal. “You’re going to find what

you’ve lost,” was the message at the Guandu Temple. When asked whether a loss

also holds the potential for a new beginning and unexpected connections, Mooni

Perry seems to have come up with a possible answer here: “creating by losing.”