“Surely there is something

insuperably barbarous in the custom of museums.”

Maurice Blanchot1

A concrete stela, ancient

artifacts, a video recording of a female dancer’s silhouette, stones, a vitrine

for relics, representational and abstract drawings in graphite, cubes, a

topographic model of an archeological site and field recording, paintings that

sit somewhere between abstraction and stain, heavy and imposing sarcophagus

from an ancient tomb, and drops of black liquid dripping from a massive

curtain. Viewing Gala Porras-Kim’s exhibition at the National Museum of Modern

and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) is like walking into a group show consisting

of works made by different artists. In each of her works, Porras-Kim adopts a

different method and chooses from mediums that span across drawing, sculpture,

video, installation and sound. For the past decade, the artist has been

investigating museum artifacts, archeological sites, and ancient architectures

with keen interest in their original mode of being as well as their

repatriation. Such concerns manifest themselves in the diverse range of her work,

where the choice of medium accords with how Porras-Kim connects with the

artifacts in question, broods over them, and calls attention to where they

originally belong. Some of them find expression in tangible forms such as

drawing and sculpture, while others culminate in intangible mediums such as

sound waves or movements recorded in video. Furthermore, Porras-Kim presents

the growth of mold and moisture in the air that continue to change over the

duration of the exhibition, calling attention to other forms of life and

agencies within the exhibition space. What begs the question here is the common

thread that runs through these seemingly discrete pieces.

Porras-Kim is interested in what

has been discovered at old archaeological sites, especially those of ancient

Egypt and Maya or the prehistoric dolmen sites. Proposal for the

Reconstituting of Ritual Elements of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan

(2019) consists of replicas of the two monoliths at the eponymous site, along

with Porras-Kim’s letter to the coordinator of museums and exhibitions at the

National Institute of Archeology and History in Mexico City. Teotihuacan,

meaning “City of Gods,” is known for its large pyramids, among which the Sun

Pyramid is attributed with special astronomical significance for its alignment

with the position of the sun. Although the two monoliths, thought to have

served ritualistic purposes, used to sit inside the top of the pyramid, they

have been moved to the museum for preservation and display, leaving their

hollow negatives behind. Their replicas have been produced by Porras-Kim with

permission from the said institute, and, in her letter to the institute, she

proposes reinserting them to where the original monoliths were, which amounts

to a call for the need to restitute their innate spiritual significance.

Porras-Kim emphasizes the possibility of channeling the efforts into the

reconstruction of the “exterior” of the ancient architectures—once displayed in

the LACMA which held and exhibited those monoliths—into resuscitation of

spirituality inherent in them. Reinserting the artist-made replica stones into

the top of the pyramid would be one possible instance, which seeks to sustain

the link between their transcendental, spiritual significance and what they

were intended for.

Next to these stones and the

letter is Two Plain Stellas in the Looter Pit at the Top of the

Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019), a graphite representation of

the view inside the top of the Sun Pyramid. Like some of its monochromatic

predecessors, Two Plain Stellas have been worked over a prolonged period of

time, with the artist repetitively and patiently filling the surface with

pencil marks. The utter darkness amounts to a poetic invocation of the

cosmology reflected in the pyramids of Teotihuacan, a city built as a tribute

to the gods. The enormous amount of labor that has been put into building the

pyramids, through which the ancient desperately sought to reach the divine and

immortality, finds its parallel in the length of time that Porras-Kim has

committed to the surface by filling it meticulously with thin layers of

graphite.

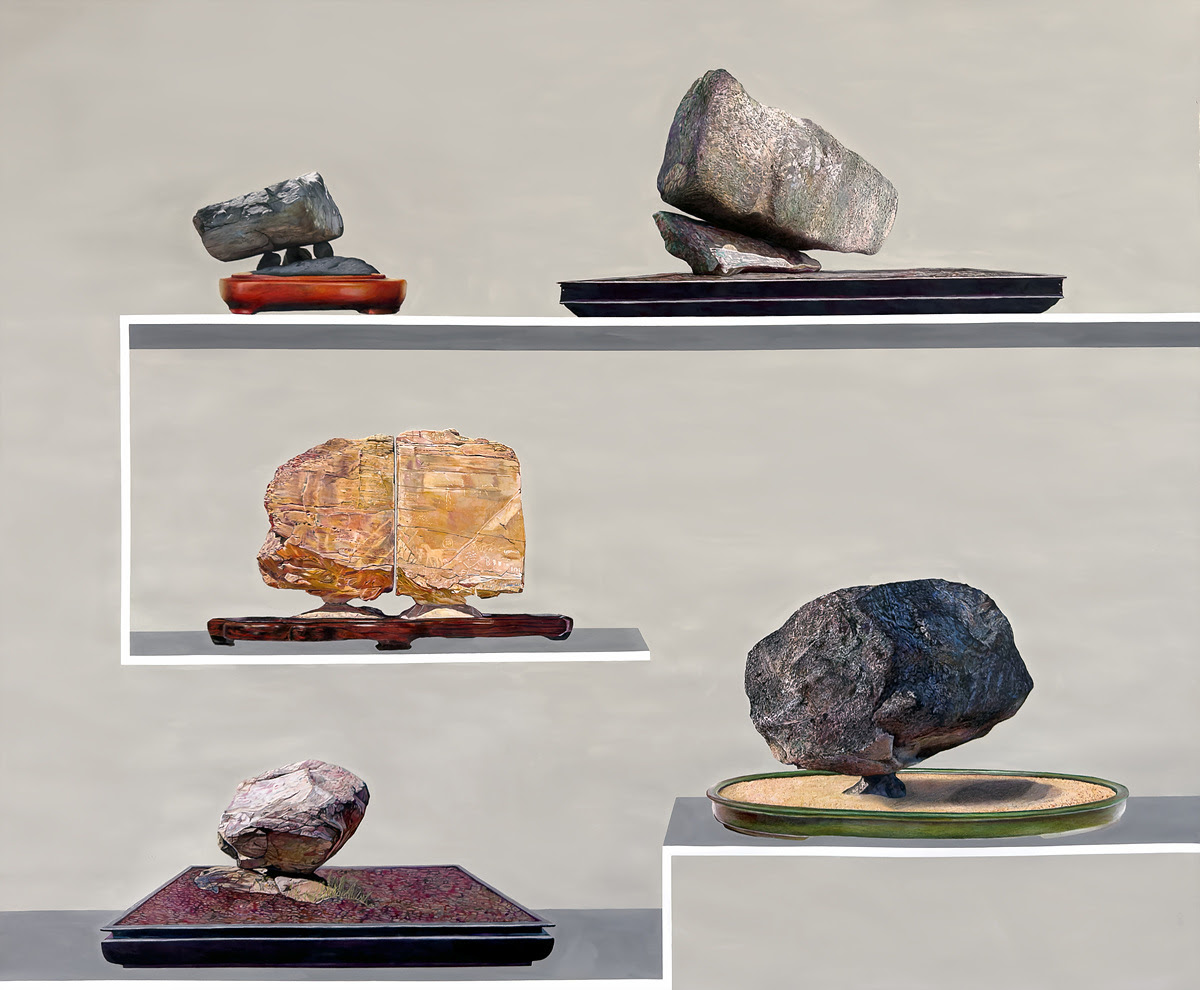

Dolmens are one of the oldest

tombs from prehistoric times. The Weight of a Patina of Time (2023)

is a new work made for the occasion of Porras-Kim’s exhibition at the MMCA, for

which she visited and studied the dolmen site in Gochang, North Jeollabuk-do

Province. Over 500 dolmens, designated as UNESCO’s World Heritage Site in 2000,

provide a glimpse into the funerary and ceremonial customs of the ancient.

Prior to the archeological assessment, however, the dolmen site was deeply

integrated into the quotidian life of the locals, where they would sundry

vegetables and laundries. Such different modes of being that cut across

multiple temporalities of this dolmen site have caught Porras-Kim’s attention,

which resulted in a two-dimensional triptych: The first is a graphite drawing

depicting what the dead would see in a dolmen—in other words, the pitch dark

inside the sarcophagus, which alludes to its funerary purpose; one in the

middle is a naturalistic rendering of the dolmen as we see it today, that is, as

a historical site and a tourist spot; the last work traces a magnified image of

moss that grow on the surface of the dolmen. The two seemingly abstract images

on both sides of the representational drawing are in fact representational

themselves: the left portrays what lies before the eyes of the dead and the

right living creatures. One communicates with the time transcended, while the

other with the time of the living.

Museum Sickness2

“The museum is indeed the

symbolic place where the work of abstraction assumes its most violent and

outrageous form. … this space that is not one, this place without location, and

this world outside the world, strangely confined, deprived of air, light, and

life…”

Maurice Blanchot, excerpt from

“Museum Sickness”3

Sunrise for 5th-Dynasty

Sarcophagus from Giza at the British Museum (2020) suggests that

the Egyptian sarcophagus, in which a dead body of a pharaoh or aristocrat is

placed, face east according to the ancient customs. The arrow drawn on the

floor marks the direction toward which the original sarcophagus in the British

Museum should be rotated, while its reproduction in the exhibition is

positioned to face east—the direction in which the sun rises and its mastaba

lies. Mastaba Scene (2022) depicts the perspective

of the dead lying inside the sarcophagus—in other words, the unfathomable depth

of darkness, which tends to be wiped out by the lighting in the museum.

Porras-Kim has embarked on these works as she began exploring the British

Museum’s collection of ancient Egyptian and Nubian funerary art during her time

at Delfina Residency in London in 2021. In her letter proposing a drawing of a

ancient desert museum large enough to envelop the vitrine, with corresponding

folds, in which the granite ka statue of Nenkheftka is enclosed, Porras-Kim

writes as follows:

“Since you “hold the

largest collection of Egyptian objects outside Egypt and tell the story of life

and death in ancient Nile Valley,” it could seem daunting to understand and

accommodate so many people’s eternal plans. Fortunately, many of the labels you

have provided in your current display already outline the specific needs for

their exposition. These guidelines might not interfere with the museography and

the day to day activities at the museum and could be an opportunity for

curating for that ancient audience to consider their positioning and views for

sights beyond the grave. Such a small step to repairing the potential

disruption caused by the relocation for the people who planned so well, can

expand our knowledge of aspects of life which might be lost to us now.”4

Museums are deeply implicated in

the Western modernity. The inseparability between the British Museum and

colonial modernity is evidenced by the fact that it holds the largest

collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt. The museums in the West

find their origin in the cabinet of curiosities—be it cabinet de

curiosités or Wunderkammer—of the European aristocracy. Not

only do they store and showcase the so-called “rarities of the world,” a notion

based on the exoticism that renders the non-Western civilizations the

mysterious other and therefore an object of curiosity, but they also acquire

their collections through colonial exploitation and looting, and thus serve as

the core space that inherits the colonial legacy of Western modernity. While

such implications inevitably raise questions regarding repatriation of the

looted artifacts to the country of origin and therefore ownership over cultural

property in the legal discourse today, Porras-Kim takes on the question of

repatriation and restoration on a more fundamental level, which pertains to not

only their place of origin but also their “original” context—that is, concerns

over the divine, religion, and afterlife out of which such relics were born.

What the artist asks is how we are to approach and restore, for example, the

notion of immortality inherent in these ancient relics from the ancient’s point

of view—the intended audience of the mysterious artifacts and sublime statues

or buildings. All of these concerns bear on the various proposals Porras-Kim

makes to the institutions, where she questions the ways in which we could

provide the spirits of the dead, alongside the associated artifacts, with

comfort and respite from the forced acculturation or displacement. For

instance, Porras-Kim takes advantage of the opportunity opened up by the fire

at the National Museum of Brazil in 2018—which marked its 200th anniversary of

its foundation during the Portuguese colonialism in 1818—during which Luzia, a

name given to the oldest mummified woman found in the Americas, has also

partially been lost along with the museum’s many other collections. Porras-Kim

insists on cremating the rest of the body that was recovered, which would free

her from the museum’s grasp as a historical object and finally put her to rest.

Her insistence entails seeing Luzia, thought to have been a 25-year-old woman

some 11,500 years ago, as a person and not an artifact for genomic

reconstruction.5

Most of Porras-Kim’s

compassionate letters were unanswered, and none of her proposals have been

accepted or realized yet. They nevertheless remind us of how the act of

collection and exhibition amounts to deracination of the ancient objects,

dehumanizes the dead in the name of museological practice, and severs the

cosmological connection and communication between spiritual worlds that

transcend not only our understanding but also our being. Instead of serving as

a space devoted to artistic creation, the museum “forces us,” Maurice Blanchot

claims, “by means of an exclusive violence, to set aside the reality of the

world that is ours, with all of the living forces that assert themselves in

it.”6 In describing the pain of seeing the restored mosaics of

Umayyad Mosque at an exhibition space, estranged from their place of origin,

Blanchot names the museum a violent and blasphemous place of abstraction.

Unlike the “real space, thus, a space of rites, of music and of celebration,”7 a

space of exhibition is open for everyone from all over the world without

imposing a particular theology. Nevertheless, Blanchot warns us, what it does

is no different than the satisfaction of Lord Elgin, an imperialist who stole

marbles of the Greek Parthenon and brought them to London. Objects such as

these marbles “offer themselves to us…in the secret essence of their own

reality, no longer sheltered in our world but without shelter and as if without

a world.”8 The grief of seeing these objects that have been

abducted by the archaeologists corresponds to the irony of the museum, a term

that signifies essentially conservation, tradition and safety, whose authority

grants status of art to things once they are congealed into permanence

without life. For Blanchot, museums are where “this lack, this

destitution, and admirable indigence”9 is laid bare in one way

or the other. Perhaps it is what Blanchot has called “a radiant solitude,” a

presence of a world, that Porras-Kim sees in the artifacts that are kept in the

safety of the museum, or, in other words, hidden away from their place of

birth.

In her two dimensional work

titled A Terminal Escape from the Place that Binds Us (2021),

Porras-Kim attempts to communicate with a mummy that dates back to the 1st

century from the Gwangju National Museum collection. Captivated by the

shamanistic traditions in South Korea that revere spirits of ancestors through

various rites, the artist spoke with a number of South Korean museum curators,

only to confirm that the dead are seen as objects of research and conservation

in their practice as well, belying the cultural expectations. Porras-Kim makes

yet another proposal in this regard, insisting on figuring out where the mummy

wishes to be buried via means of shamanic ink divination. This process involves

dropping ink in a puddle of water while potentially making contact with the

spirit of the dead, and knowing that there could be information of a location

within the incoherent patterns it creates, and transferring them via paper

marbling, which could contain the wish of the spirit. The colorful swirls created

thus, which give the look of modern abstract painting, not only potentially

speak on behalf of the spirit but also serve as a testament to Porras-Kim’s

commitment to their ontological reinstatement.

Such a practice of hers belongs

to a type of institutional critique situated in the tradition of the

avant-garde art. Her letters provide a glimpse into the activist side of her

practice, evidenced by Porras-Kim’s insistence on showing respect for the dignity

of the dead, the ancient cosmology, and the spirits of the ancestors—in other

words, things that lie beyond the purview of Western rationality and by

extension colonialism. These are addressed to none other than the museums, the

coffin-like institutions that exemplify the complex matrix of Western

rationality where law, bureaucracy, and academic specialization intersect.

Instead of opting for radical interventionist tactics commonly associated with

such a practice, however, Porras-Kim employs rather familiar, traditional

mediums such as drawing, and sculpture for unfolding her profound ontological

insights. While her proposals, persuasive and composed in their style and tone,

is cut across by the meridian of the animistic world of spirits, the lyricism of

her work—evident in the night and the stars, the glimmer of sun shining through

closed eyes, the asymptotic horizons, or the songs made in tribute to the

forbidden love between two brothers—carves out a soft, delicate space for

poetics. In Porras-Kim’s work, the archeological artifacts shed themselves of

their designation as object of knowledge, marked by titular information such as

chemical and material composition or chronology, and reach out to the viewer in

their ontological precarity and loss, their mysteriousness and solitude.

Through such a nuanced approach, Porras-Kim enables the viewer to resonate

deeply with the accountability of museums as a space for the spirits of the

ancient and their worldview as well as restoration of their dignity but also

the ontology of archeological objects.

Porras-Kim’s lyricism persists

in Asymptote towards an Ambiguous Horizon (2021),

a series of twelve graphite drawings depicting the changing landscape of

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey—a neolithic World Heritage Site designated by

UNESCO—over twenty-four hours at a two-hour interval. The work also features a

soundscape of the site, which is played back from a scaled-down topographic

model of the site. Göbekli Tepe or “Potbelly Hill,” one of the world’s oldest

known human-made structure that dates back 12,000 years, harbors a secret of an

ancient architectural technology that surpasses the Pyramid of Giza or the

Sumerian civilization in time, with the most notable feature being twenty or so

circular enclosures made up of T-shaped stone pillars that amount to nearly two

hundred in total. The site had been buried 760 m above sea level when it was

discovered by coincidence, and excavation is still ongoing. Although it is

believed to have been a temple, some speculate that it was built to observe

Sirius or other astronomical events.

When the site visit became

unfeasible in 2020 due to COVID, Porras-Kim sought help from astronomers and

Google Earth for her drawings: the skyscape, northwest to the site, has been

drawn according to the star formation from 12,000 years ago provided by an

observatory, whereas the current day landscape is based on images generated by

Google Earth, where the user is able to change the position of the sun and by

extension the lighting of the image. The drawings of the ancient skyscape

juxtaposed with the modern landscape reconstruct the twenty-four hours at

Göbekli Tepe, during which heaven and earth draw ever closer to each other at

the horizon but never meet. These lyric drawings, which aspire to the

primordial and incomprehensible time, quietly move in and out of multiple

guises—a personal tale, myth, mystery, and state-owned resource—as they, in a

purely auditory sense, traverse across the soundscape composed of various

sources ranging from the wind passing through the site to video- and

voice-recordings pertaining to the site.

Soul Design by Mold and Moisture10

No actual artifacts are found

inside the vitrine. What persists before the viewer’s eyes, however, are their

semblance, their existence which is their soul. In her solo exhibition at Leeum

in 2023, Porras-Kim replaced one artifact at the museum with paper pieces

arranged in a way that casts a shadow identical to that of the original object

when lit by the lighting. Depending on the angle from which they are looked at,

the shadow blurs or sharpens, in the latter case of which reveals the

enigmatic, captivating contours of the replaced object. Through this shadow

constantly coming in and out of existence, the artifact enters a nonmaterial

state, or, in other words, engages in spiritual communication.

“What if we were to

imagine the soul as an “event,” as something that cannot be owned but only

exists in the intermediary realm? Wouldn’t this enable us to pose the question

of animism differently—not as a question of what possesses a soul, but as a

question of the different forms of being animated and animation, understood as

a communication event? What if “the soul” was the medium of such event? After

all, each of us is capable of distinguishing an animated conversation from an

un-animated one—however, articulating this difference or even objectifying it

is incomparably harder. And “exhibiting” this difference can virtually only be

done in the form of the joke or the caricature.”11

The aforementioned work in paper

fragments and their shadow, Gourd-shaped Ewer Decorated with

Lotus Petals Display Shadow (2023), is shown inside of glass

vitrine at the antiquity section of Leeum, which brilliantly resonates with

what Anselm Franke explains in his notion of “soul design,” amounting to a

witty sculptural event that sets in motion the animistic property of the

archaeological object. This is to say that Porras-Kim’s work entails far more than

simply preaching how ancient spiritual traditions ought to be respected by the

museums. Porras-Kim engineers and facilitates “animated conversations” in her

works—or objects. In fact, animism is native to conversations in contemporary

art, and she employs various conceptual strategies to animate such

conversations in visually concise, minimalist forms.

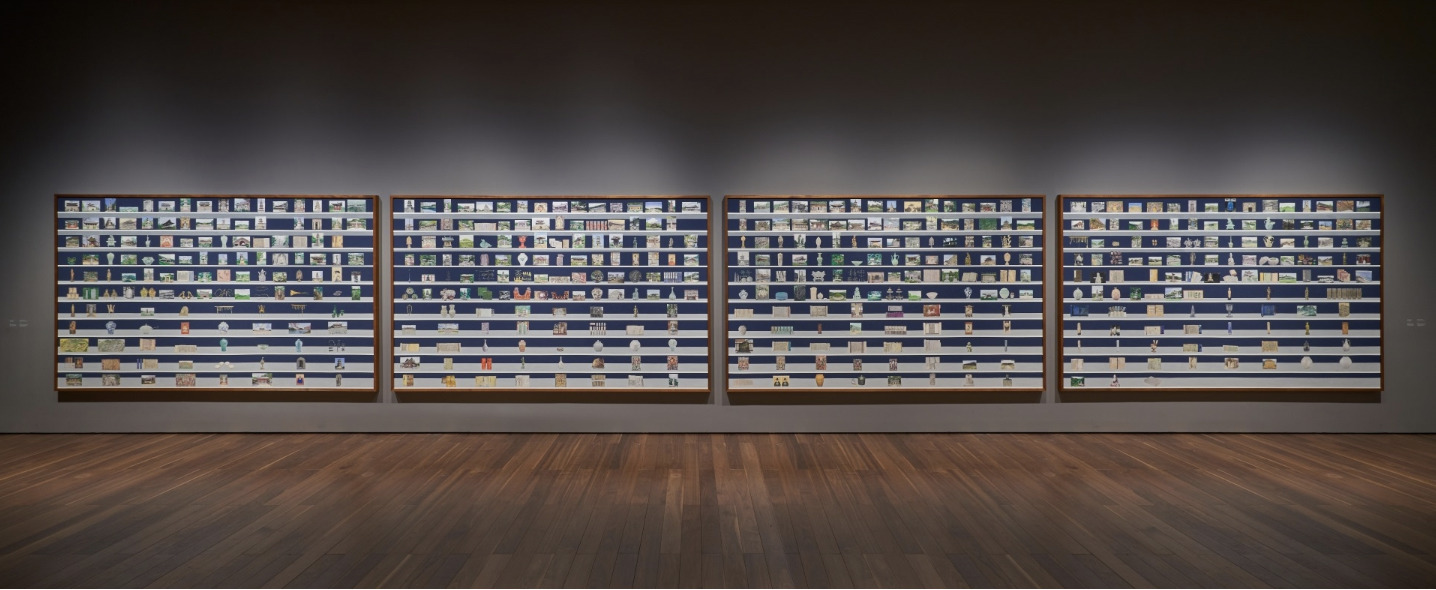

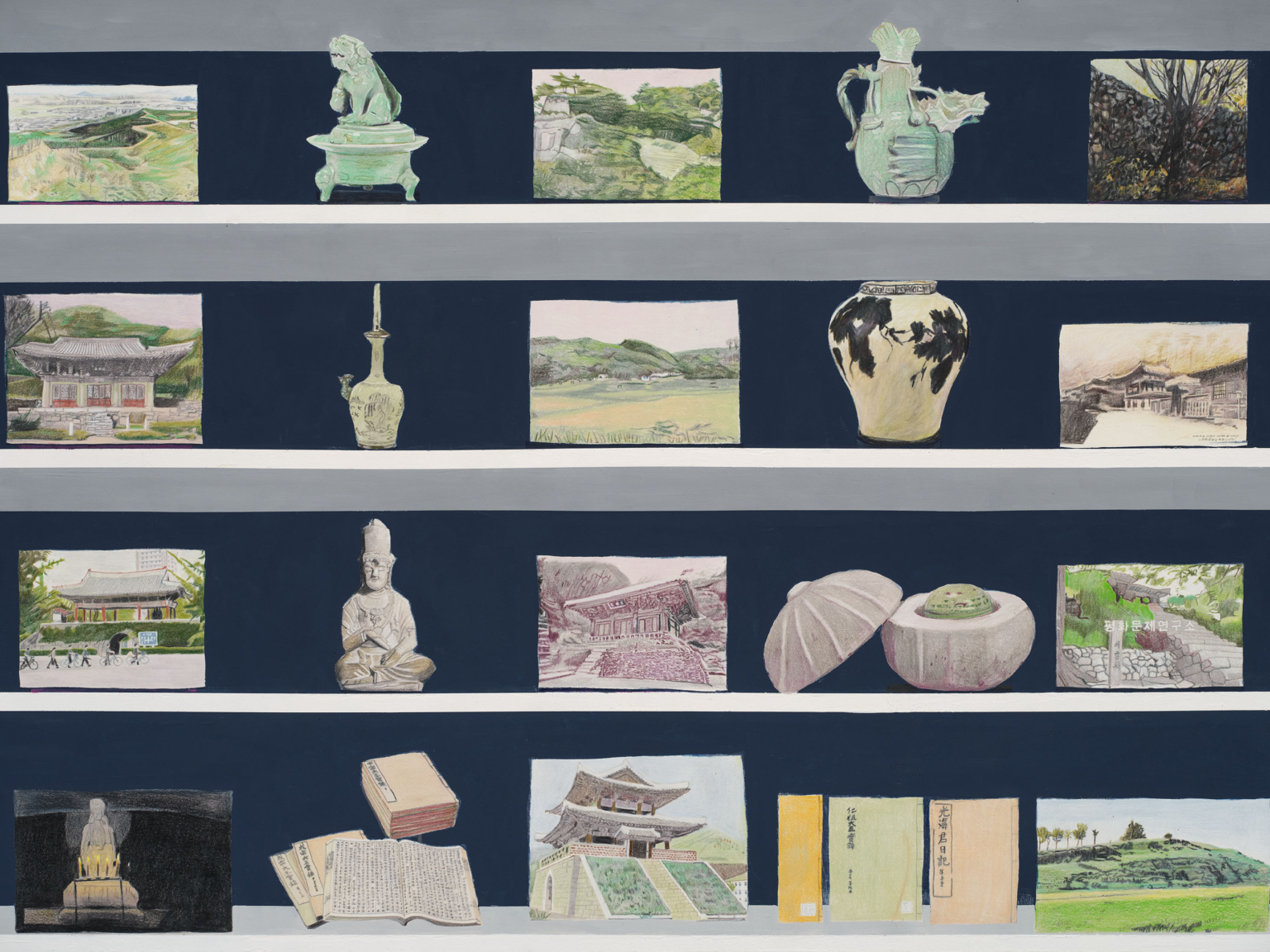

303 Offerings for the

Rain at the Peabody Museum (2023) is a two-dimensional life-size

reproduction of ancient artifacts discovered from the Chichén Itzá cenote, one

of the sacred sinkholes with exposed groundwater on the Yucatán Peninsula of

Mexico, within the dimension of 183 × 183 cm (or 72 × 72″). Originally intended

as offerings to Chaac, the Mayan god of rain, these objects were found

submerged, dredged and are currently in the storage of the Peabody Museum at

Harvard. They have inspired Precipitation for an Arid

Landscape (2021)12, a work that takes copal13—one of

the most commonly found material in the cenote and a binder—and dust collected

from the storage at the Peabody. It is placed inside a glass case full of

moisture, which is the result of instructing each exhibiting institution to

devise a strategy for bringing rain water to the installation. According to

Porras-Kim, this is a reunion between Chaac and the offerings made to him, or

consolation for the displaced spirits, accomplished at last by taking advantage

of the very discretionary power of the museum.

For some of her work, Porras-Kim

regularly makes requests for particular arrangements for moisturization to the

museums. In Out of an Instance of Expiration Comes a Perennial

Showing (2022), Porras-Kim cultivates mold spores obtained from

the museum storage on a muslin cloth by providing it with moisture. The mold

spreads and evolves over time, producing a new image of abstract patterns on a

daily basis. In the back end of the exhibition space hangs Forecasting

Signal (2021), where invisible moisture collected by the

industrial dehumidifier finds its way onto a hanging burlap canopy soaked in

liquid graphite. The water, when accumulated enough, drips through and leaves

its trace on the panel installed underneath. The drops of black liquid represent

the amount of moisture accumulated throughout the exhibition period,

“signaling” the minute changes in the indoor climate such as humidity level.

The climate controls of the museum are a telling sign of its built-in

aspiration toward a clinical space, a sealed cube where microorganisms remain

inactive. The events taking place during the exhibition are none other than the

interaction between organisms and the microbiome that animates one another.

There is a bizarre sense of humor or irony in bearing witness to the

reincarnation of what ought to have been exterminated in the museum. What first

catches the attention of the visitors in these two works are the patterns of

the molds and graphite stains or the way that the burlap hangs from the

ceiling. Although for the viewer they take the guise of traditional mediums

such as drawing, sculpture or installation, the set of concerns and

performative gestures that Porras-Kim presents before her audience, from ritual

for spirits of the ancient to exhibition that consists of conversations between

objects, spring from the comprehensive inquiry into things that ought to

inhabit the museum.

Porras-Kim has continued to

produce works that reflect on the symbolic structures of the Western

rationality and colonialism through research into specific archeological sites

and collections, imagination and ontological understanding of archeological objects.

Her works occasionally manifest in poetic moments of coming into contact with

the animist cosmology, where, traversing a wide range of

approaches—institutional-critical, conceptual, poetic, pictorial, etc., the

soul design of objects in contemporary art intersects with ancient cosmology.

Porras-Kim appeals to the spirit inherent in the ancient objects as if facing

an actual person in her own right, summons the stars in the ancient night sky

as if reciting poems, sees and speaks on behalf of the dead and their relics,

and engenders conversations between the museums and their macrobiotic

environment. The archaeological objects are, in some sense, the age-old

diasporic beings. Communicating with these objects takes place in the communal

time shared between the humankind and their ancestors. To whom does the death

of the ancient belong? What does it mean to “own” an object from a world that

far exceeds our measure of understanding? In what ways should museums exercise

their discretion? What do we see and not see in the museum—a space saturated

with the very act of seeing? How do archaeological objects and works of art

pave the way for animated conversations? These are critical and crucial

questions that lie in Porras-Kim’s decade-long artistic pursuit. In conjunction

with these inquiries, the artist demands and exercises alterations while

relaying age-old yearnings from the afterlife. Her works are vibrant—individual

entities that manifest vitality, memory, and solace. Not only do they aspire to

communal restitution, but they also shine through as events of animism.

1. Maurice Blanchot, “Museum

Sickness,” in Friendship, trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg (Stanford CA:

Stanford University Press, 1997), 45.

2. This expression takes after a

title given to one of the chapters in Blanchot’s Friendship, “Museum

Sickness.” Ibid..

3. Ibid., 47.

4. This is quoted from

Porras-Kim’s letter to Daniel Antoine, Acting Keeper at the the British

Museum’s Department of Egypt and Sudan. The letter is also shown alongside the

works in the exhibition.

5. This is the content of

Porras-Kim’s Leaving the Institution through Cremation is Easier than as a

Result of a Deaccession Policy (2021). The letter is showcased next to a

framed sheet of paper towel with an ashen handprint.

6. Blanchot, Friendship, 48.

7. Ibid., 47.

8. Ibid., 49.

9. Ibid, 48.

10. The term “soul design”

derives from the chapter in Anselm Franke’s catalogue book for the

exhibition Animism. See Anselm Franke, “Animism: Exhibition and Its

Concepts,” in Animism (Seoul: Ilmin Museum of Art, 2013), 24.

11. Anselm Franke, Animism,

24-25.

12. For the occasion of the

exhibition at MMCA, this work is exhibited alongside 303 Offerings for the

Rain at the Peabody Museum.

13. According to Porras-Kim,

copal is a resin extracted from trees and used as incense for ritual.