The

“Korean Wave” (Hallyu), which began with television dramas in China in 1997,

has since continued through K-pop and now extends beyond Asia, captivating

audiences around the world. In fact, the term “Hallyu” was originally coined by

Chinese media to describe the widespread popularity of Korean popular culture.

Over time, its meaning has expanded to refer more broadly to the phenomenon in

which people overseas admire and embrace Korean culture itself.

Looking

back over Korea’s 5,000-year history, it is difficult to find another moment

when Korean culture enjoyed such widespread popularity across so many regions

abroad. There are historical records of Goguryeo’s performance arts and Baekje

music attracting attention in neighboring parts of Asia during the Three

Kingdoms period, and cultural exchanges continued intermittently thereafter,

but these were generally limited to specific countries or modest in scale.

Contemporary Hallyu, however, has spread from East Asia to the rest of the

world, inspiring enthusiasm among young people overseas. This is undoubtedly an

event worthy of record in the history of Korean culture.

Faced

with this unprecedented phenomenon of Hallyu, many have likely asked themselves

what it is about “us” that appears so appealing, and why we have been able to

produce such cultural output. In truth, this wave presents a clear opportunity

to firmly establish Korea’s standing as a cultural force on the global stage.

Accordingly, voices from across society have proposed various perspectives on

how Hallyu might continue to grow, rather than remain a passing trend, and go

on to lead global culture and the arts.

However,

it is important to emphasize that such efforts must begin with a reflection on

Korea as a nation and on the identity of Koreans themselves. In other words, in

order to seek answers, we must first return to the fundamentals.

Behind

well-crafted songs and impressive choreography performed by visually striking

stars, behind entertainment agencies that understand global markets and deploy

sophisticated strategies, and behind the beautifully composed images, actors,

and narratives of dramas and films that captivate audiences worldwide, there

lies Korea as a country and Koreans as people.

Today,

perhaps driven by the popularity of Hallyu, programs featuring open auditions

for aspiring singers, announcers, and actors—along with the process of

selecting them—have proliferated, attracting thousands who hope to become

stars. At the same time, shows in which established celebrities compete

artistically for the top position have captured the attention of the entire

nation.

Listening closely to the opinions of judges on these programs reveals a

common thread: rather than imitation of established models, they seek potential

in those who, even if still imperfect, preserve their individuality with

sincerity and possess strong fundamentals. The belief is that only those who

understand their own origins and build upon a solid foundation can give rise to

something genuinely new and valuable. No matter the field, appearances alone do

not endure. Just as well-tilled soil yields richer harvests from the seeds sown

upon it, this principle is not a new one.

The

renowned psychoanalyst Clotaire Rapaille argues in his book ‘The Culture

Code’ that understanding culture requires first identifying the archetypes

underlying people’s behavior and thought. He also emphasizes that emotion lies

at the base of the cultural unconscious that forms these archetypes. Has it not

been said that art is ultimately a search for identity?

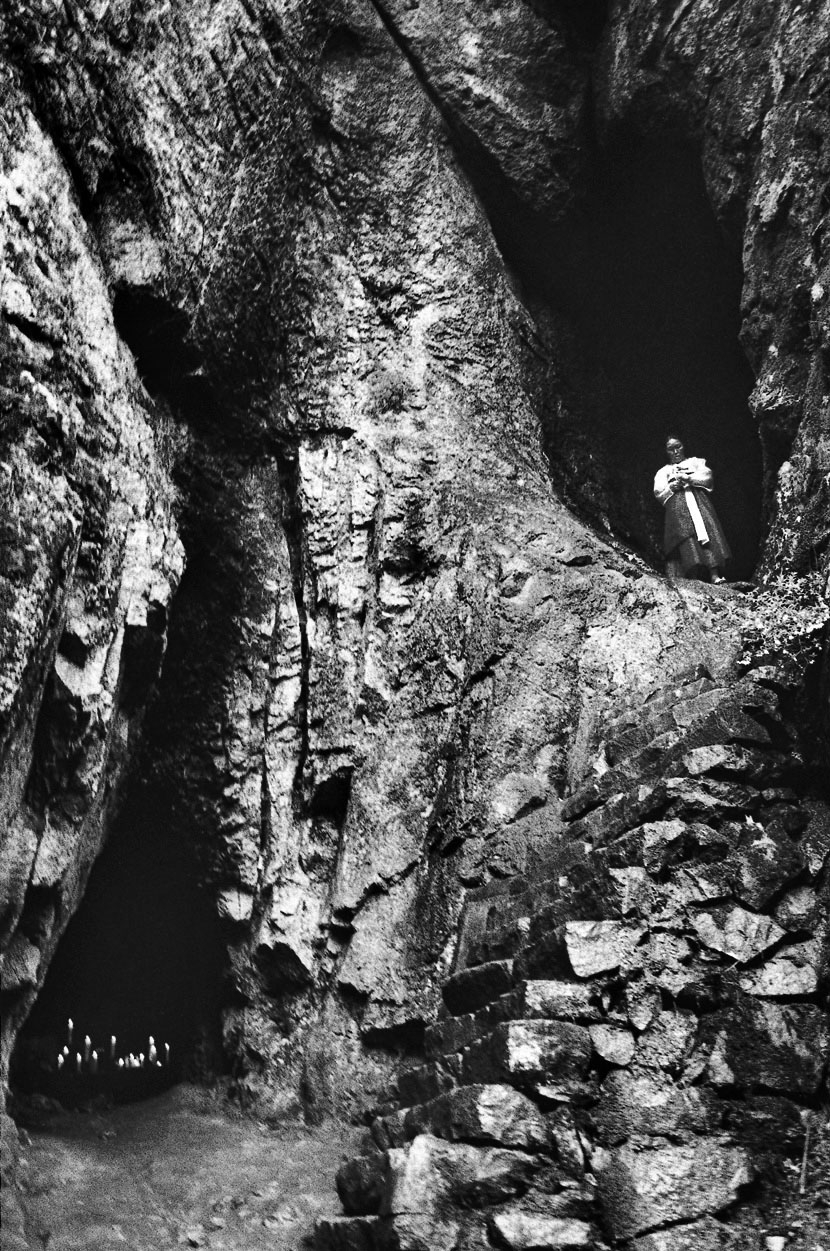

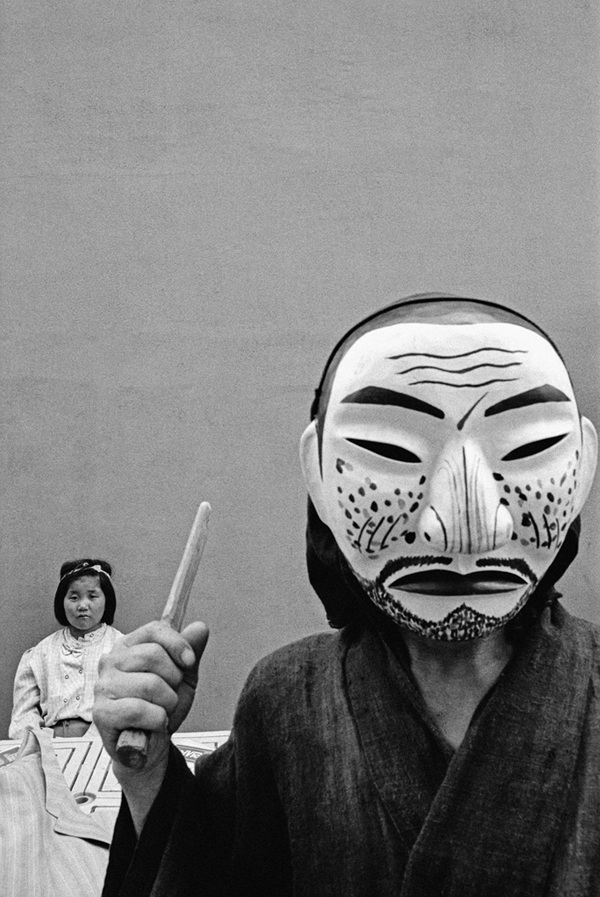

To understand the

underlying strength of “Korea” and “Koreans” that is now astonishing the world,

one can encounter Korea’s traditions, landscapes, people, emotions, and spirit

through the perspectives of leading Korean photographers who have long sought

to articulate Korean identity in their work. Through their photographs, it is

hoped that viewers may gain a more concrete understanding of the latent

consciousness and sensibility that exist within us.

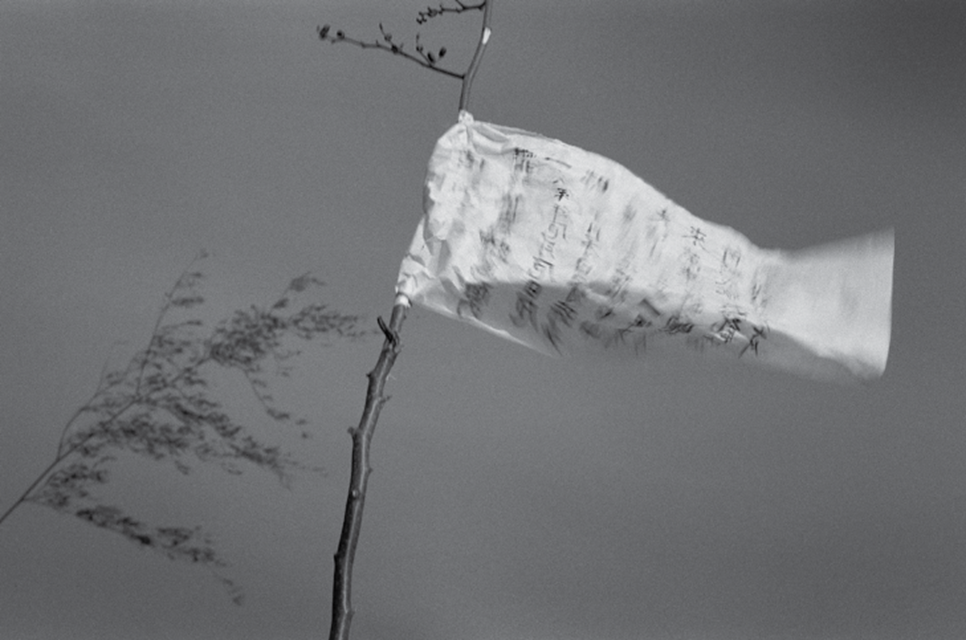

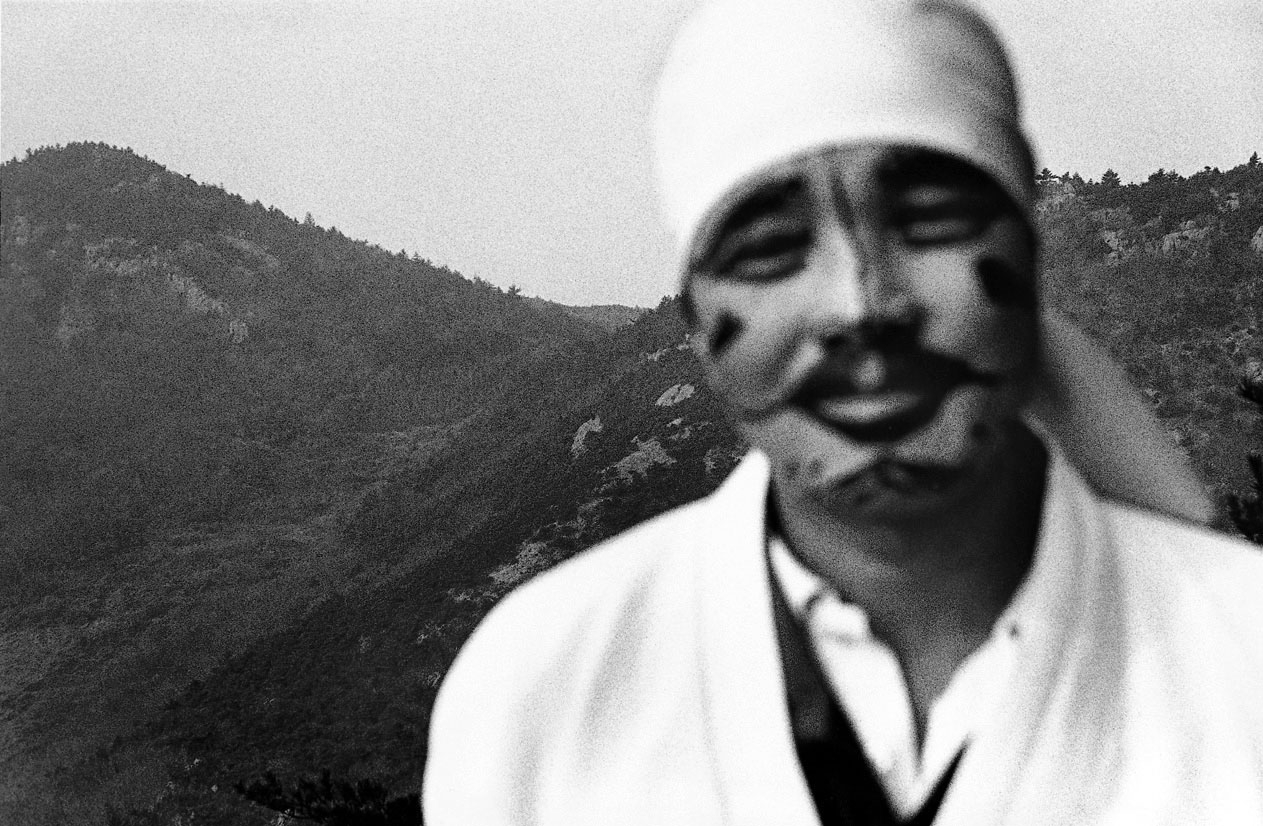

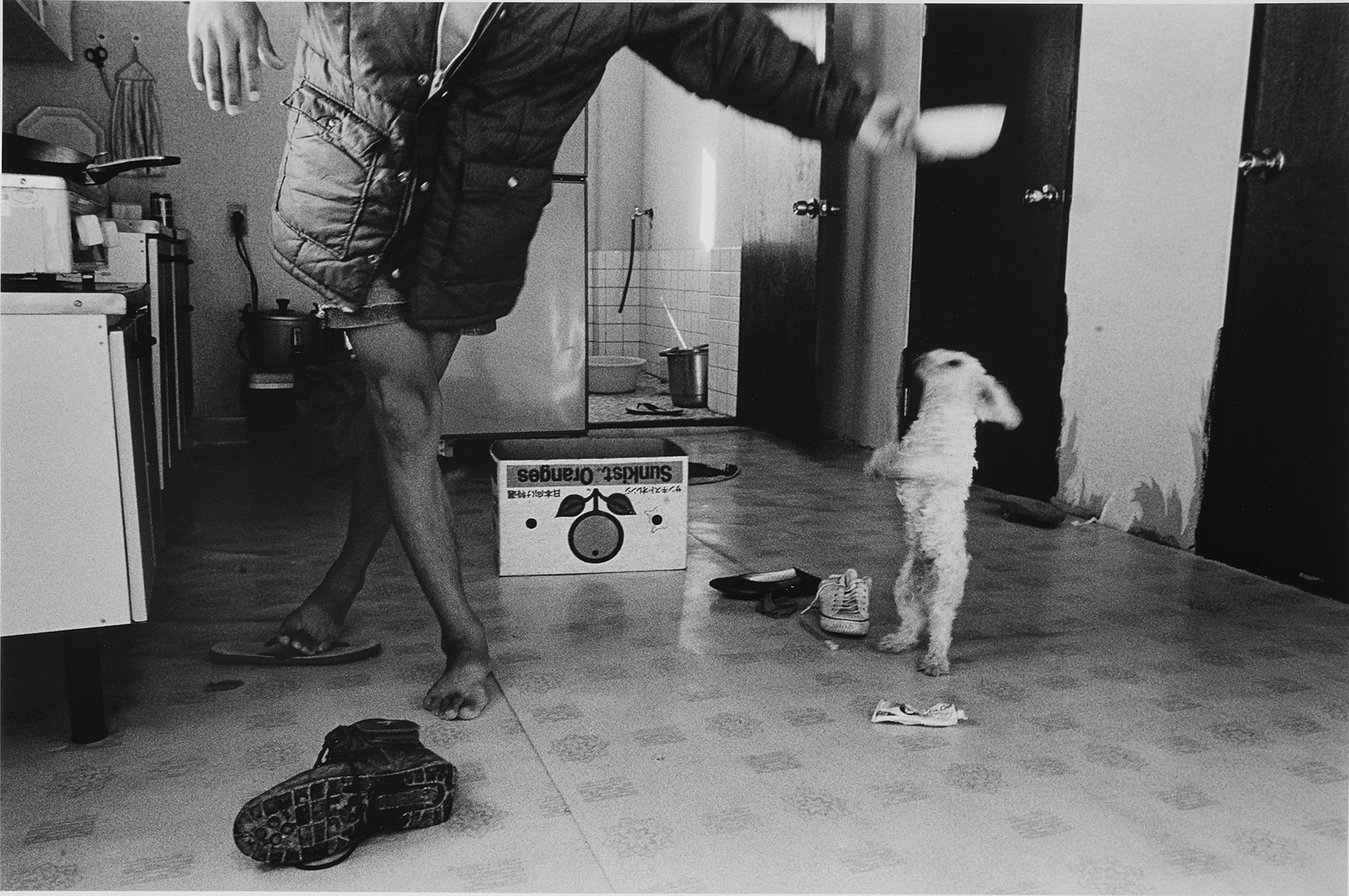

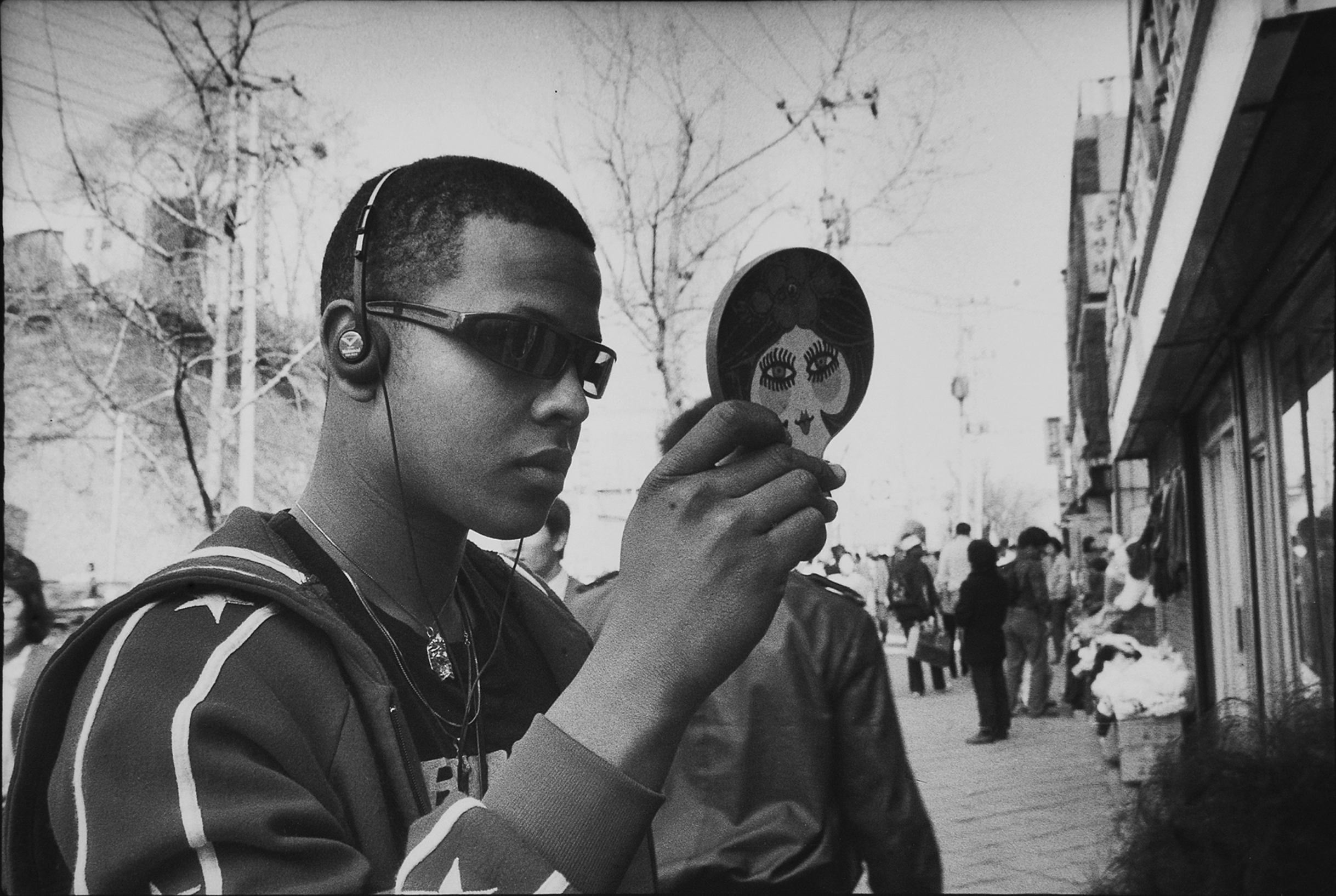

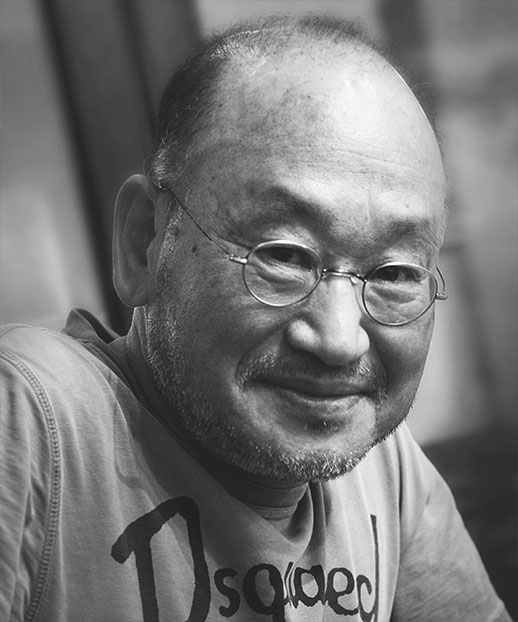

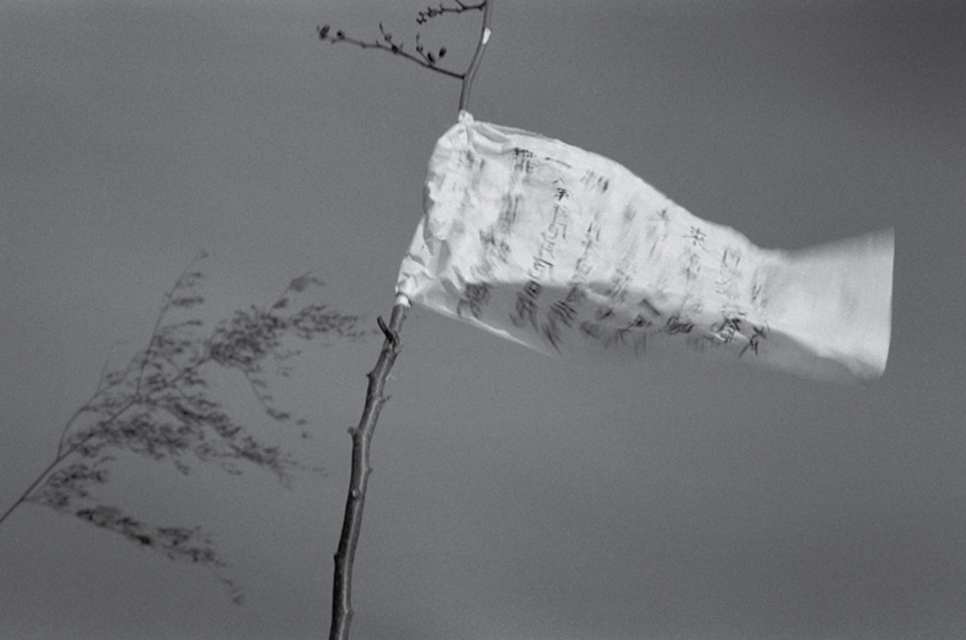

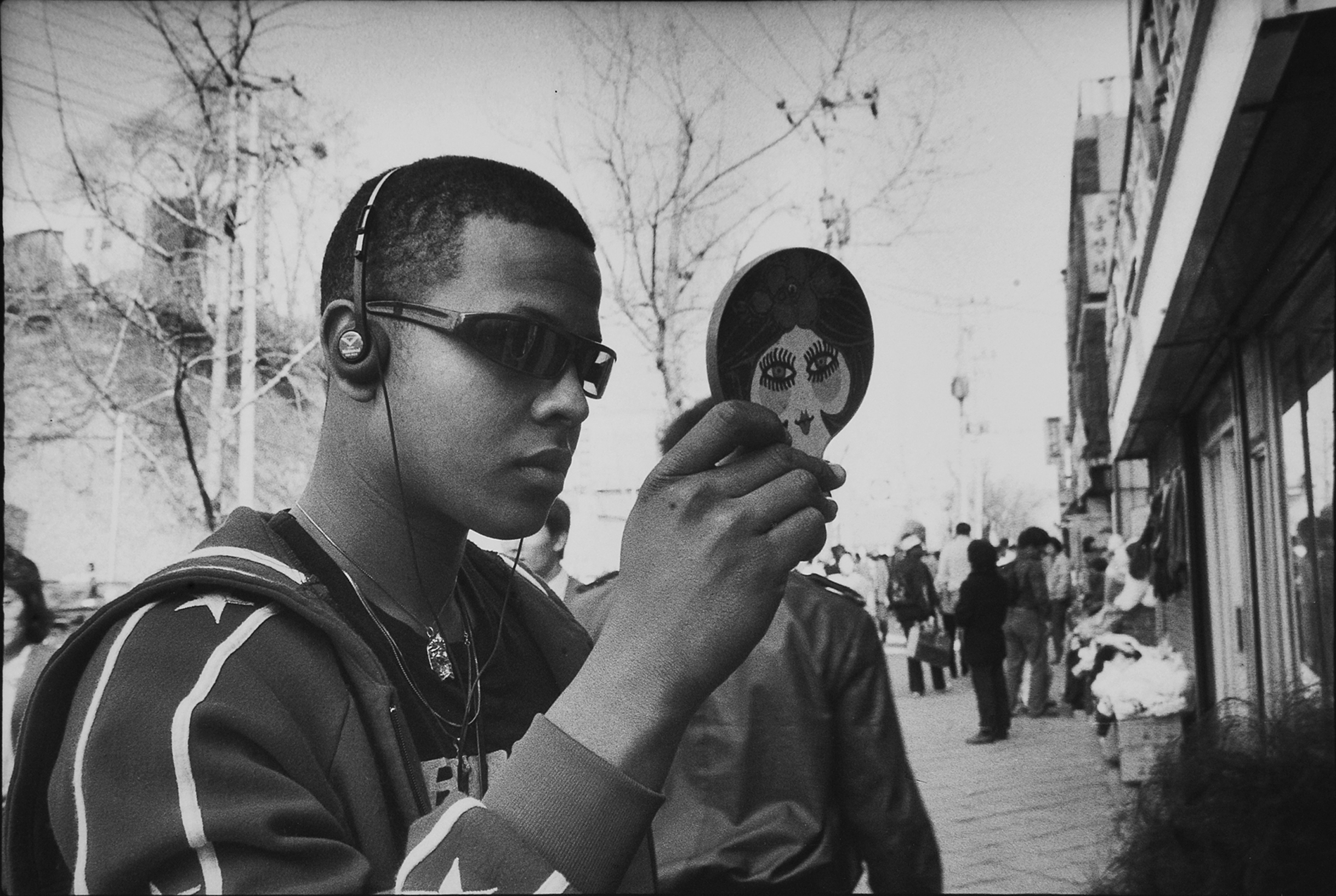

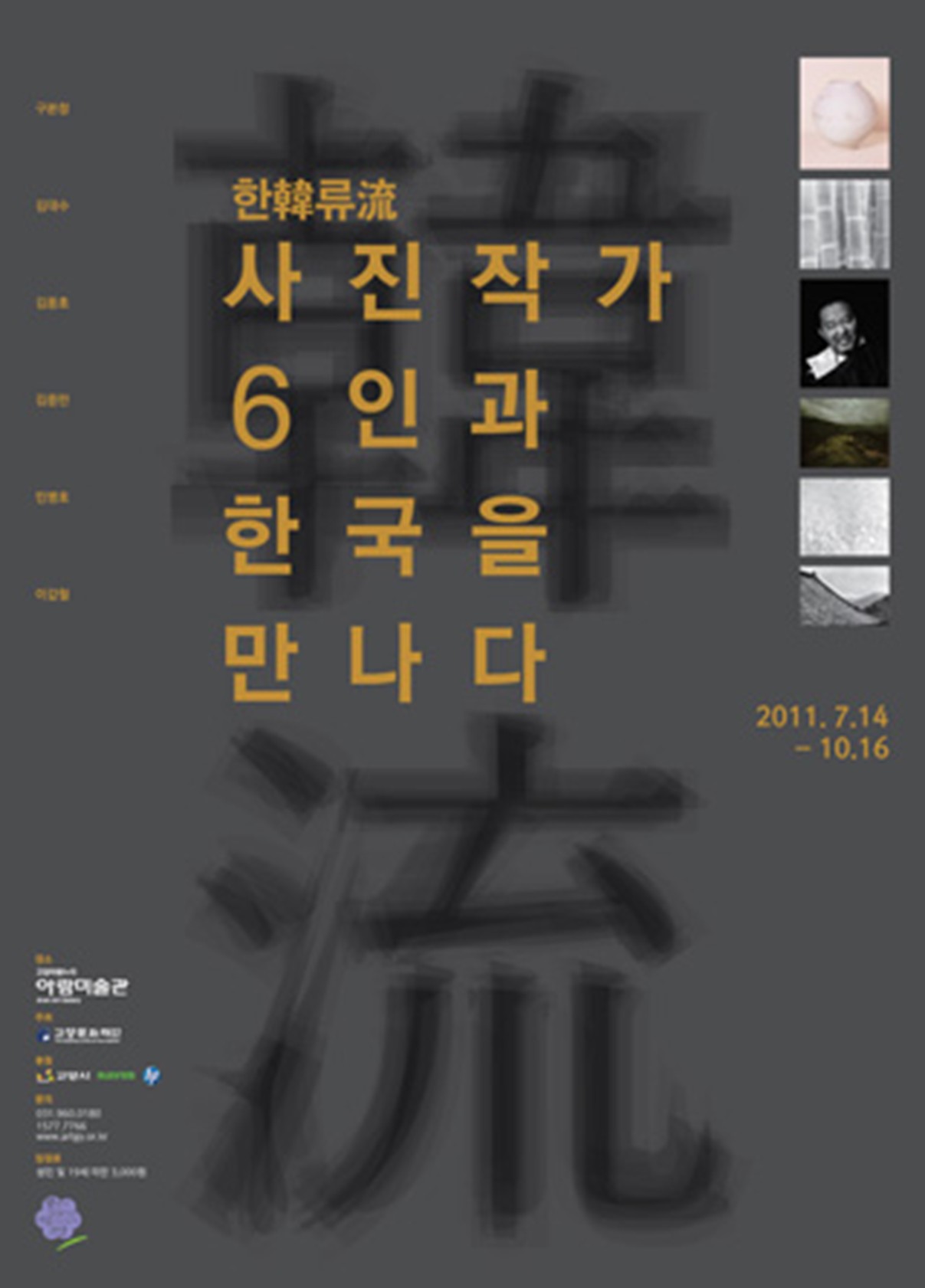

The

exhibition begins with Koo Bohnchang, who captures in photographs the simple

yet elegant beauty of white porcelain, from small water droppers to moon jars.

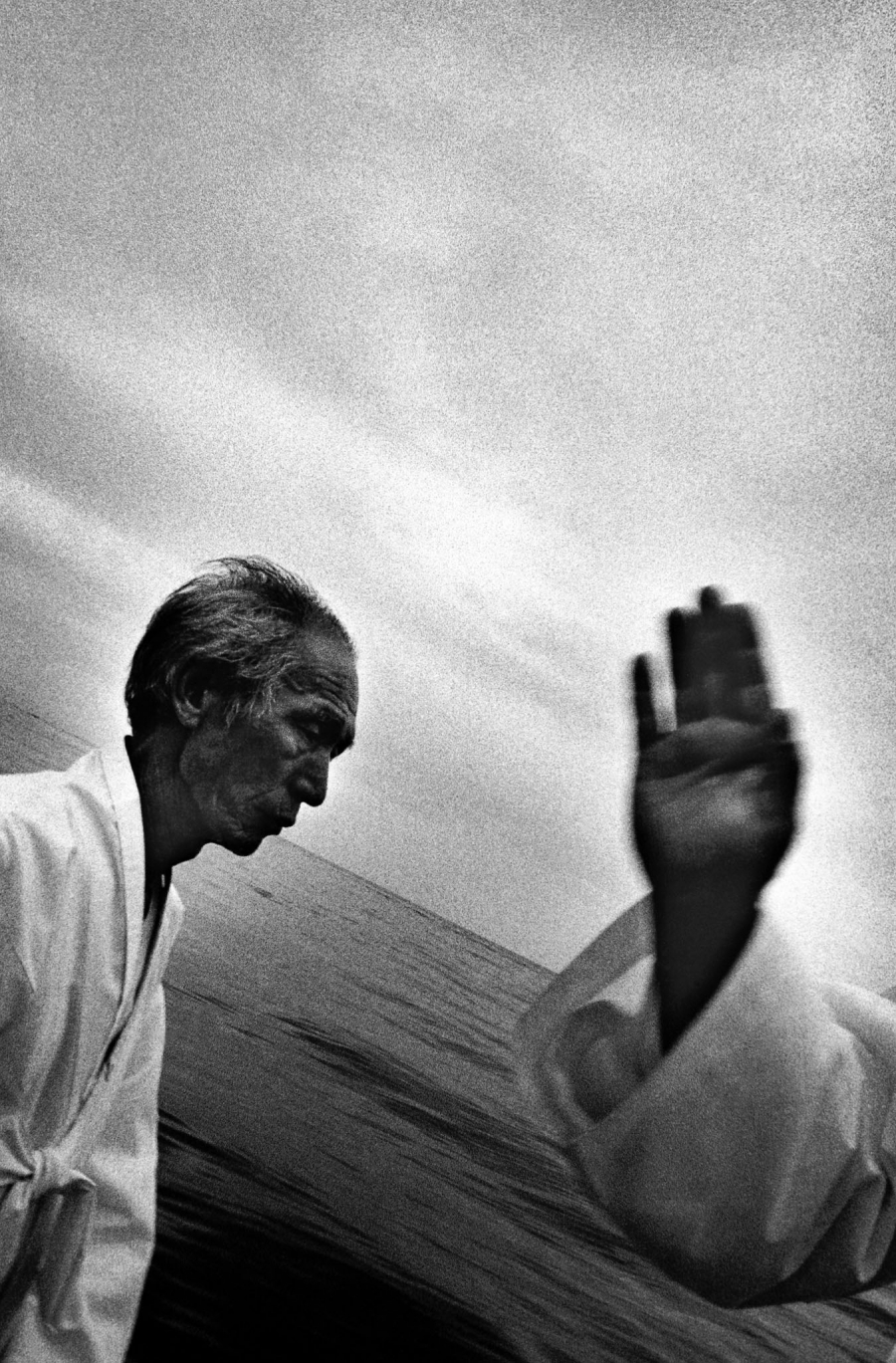

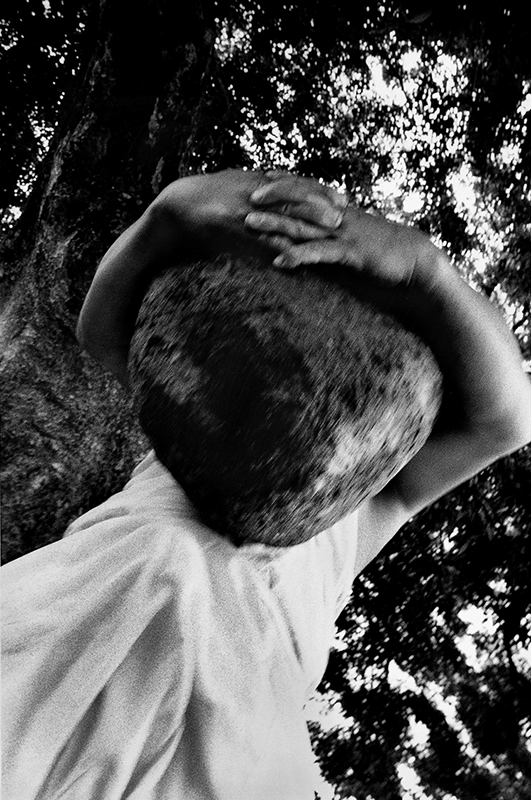

It continues with Lee Gapchul, who grapples with Korean emotion and landscape,

expressing tradition and inner worlds through a photographic language that

feels almost possessed; Kim Daesu, who discovers the quiet yet often forgotten

beauty of the Korean spirit that transcends time in bamboo; Min Byungheon, who

renders Korean sensibility as if painting a landscape with photography through

the subtle gradations of ink on mulberry paper; Kim Jungman, who photographs

the beauty of Korean nature with heartfelt sensitivity; and concludes with Kim

Yongho, who records the enduring passion and depth of Korea’s cultural masters,

as well as the hopeful faces of 365 Koreans.

Through

this exhibition, it is hoped that visitors will discover the living, breathing

culture of our time, and recognize aspects of ourselves that have been moving

unconsciously in the depths. Ultimately, the exhibition seeks to serve as an

opportunity to reflect on and explore a more genuine meaning of “Hallyu.”