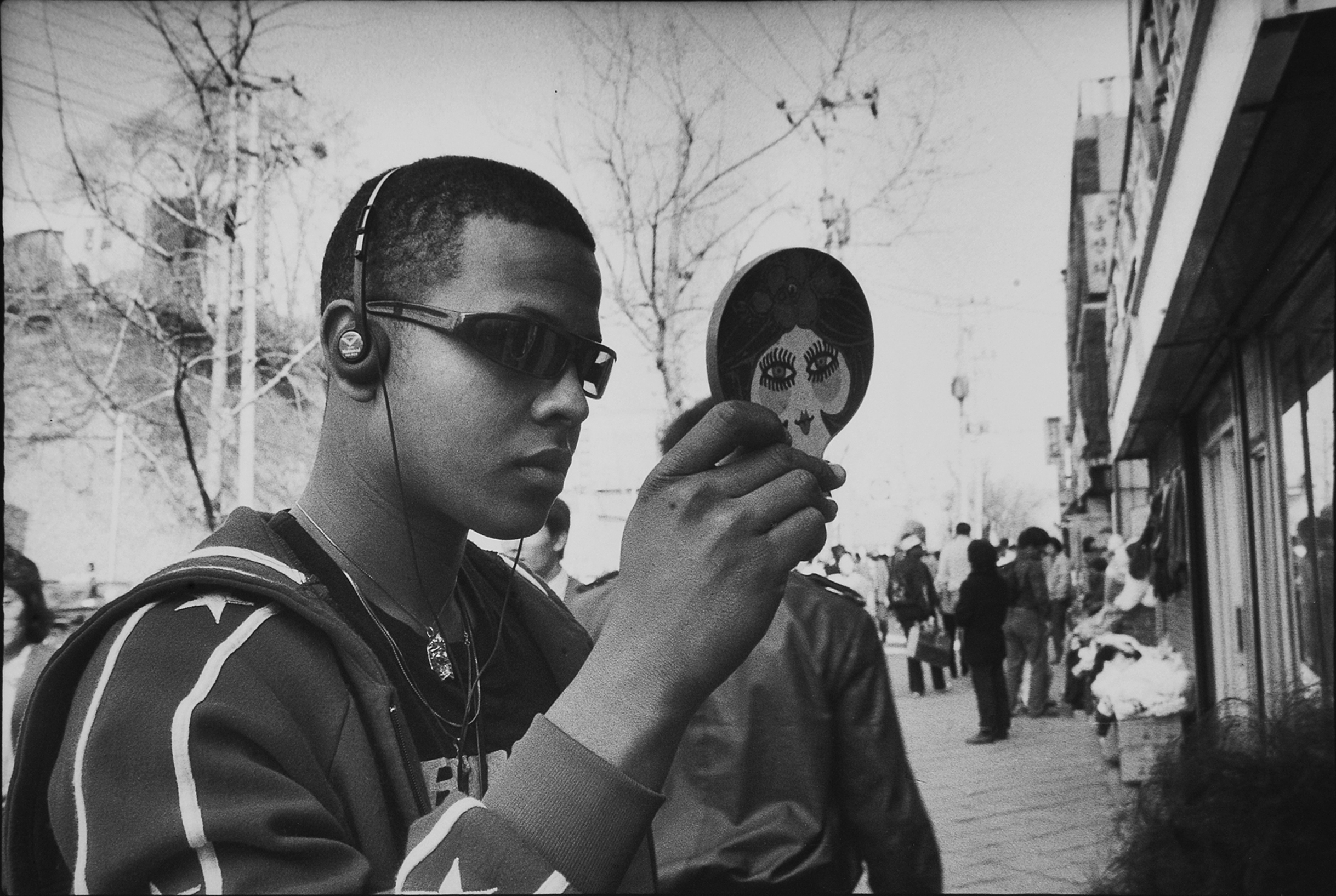

Lee

Gapchul is a fortunate photographer. He is one of the rare artists whose work

is deeply understood by a wide audience. When his photography began opening

toward a singular world in the 1980s, he was already sharing a poor yet

passionate life with fellow artists in a dark room in Seongnam, and his work

was never ignored by critics.

Rejecting

convention, automation, and ideological rigidity, he continuously questioned

photography itself, searching in all directions. In this sense, his photography

was an experiment—and that experiment was the work itself. This is why he is

often called “a photographer’s photographer.”

From

the beginning until now, Lee has consistently used Tri-X film. With its high

sensitivity and fine grain, it was well suited to capturing the vivid gestures

and breath of people on this land.

Those who witnessed 《Conflict and Reaction》 (Kumho Museum of Art,

2002)—created with animal-like responsiveness, moving “three times more” than

others—described it as a shock. It received praise such as “hair-raising” (Park

Young-taek), “a masterful incision into Korean han” (Kim Yong-taek), “an approach

to the deep unconscious of Koreans” (Yuk Myung-sim), and “captured with

extraordinary sensitivity and speed” (Kang Woon-gu).

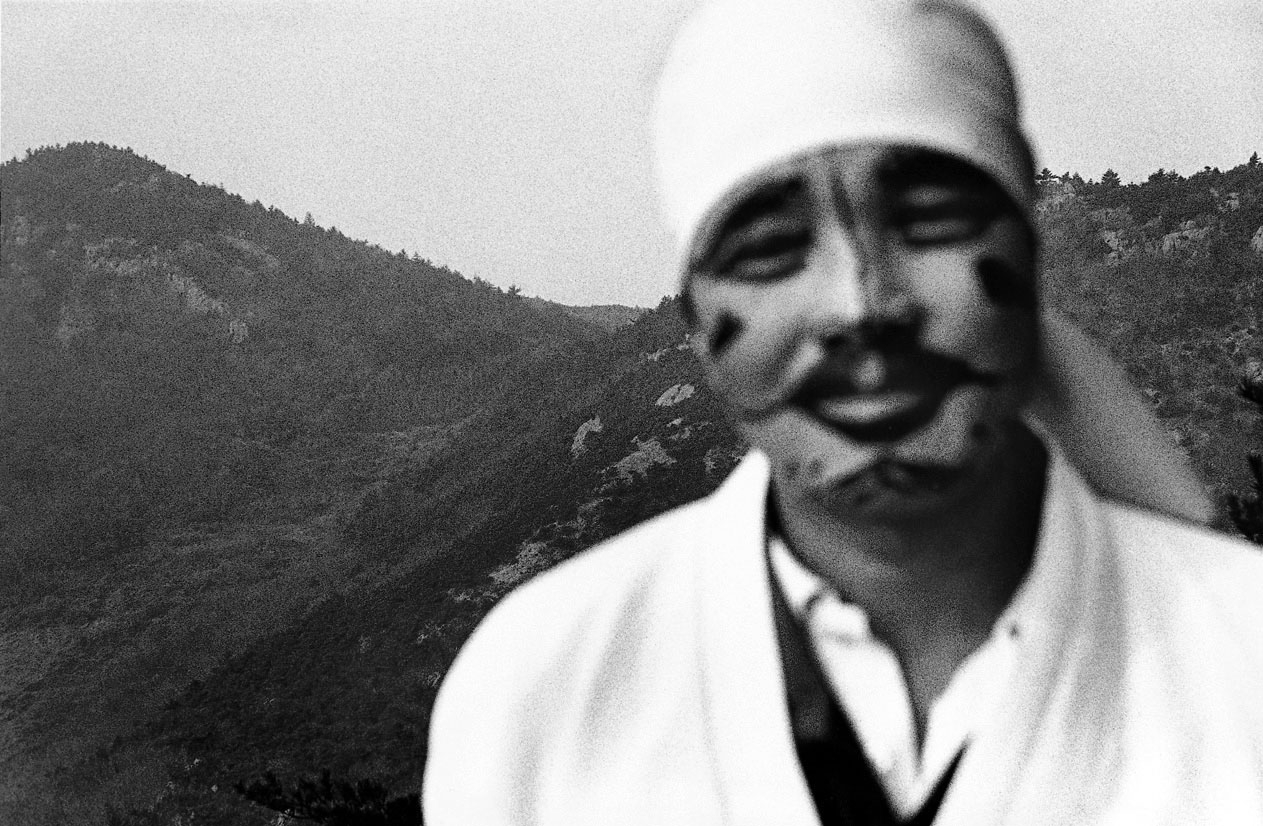

The

images he produces—where no precise form is clearly visible and rough

black-and-white tones collapse and rise again within the frame alongside

radical compositions—overturn conventional expectations that photography must

faithfully represent its subject. These were images unseen in Korean

photography until then, revealing photography not as a mere tool for producing

evidence, records, memorials, or art objects, but as an active genre inherently

endowed with infinite potential for transformation.

The conceptual shell of

photography as something that depends on and imitates its object has long since

been stripped away. As a result, Lee was described as an ascetic of

photography, a Zen monk engaging in kōan

dialogue through the camera, and a medium who soothes the Korean emotion of han through images. Within his photographs resonated a

peculiar sound—like a wind chime—that encompassed space, people, their

situations, and the totality of relations between them.

Figures never appear

whole; they emerge abruptly, unexpectedly, heightening tension and compelling

repeated viewing. At a time when landscape photography largely derived

aesthetic value from recording surface appearances alone, this strange aura

inevitably drew attention. His work came to be recognized as photography that

deeply embodies Korean sensibility, elevating him as a leading figure of the

next generation of Korean photographers.

The

two solo exhibitions—《Conflict and

Reaction》 (Kumho Museum of Art, 2002) and 《Lee Gapchul Photography》 (Hanmi Museum of

Photography, 2002)—marked the brilliant flowering of his career. If these

exhibitions compiled works produced over more than a decade since the early

1990s, documenting local rituals, shamanistic rites, and folk ceremonies across

provincial regions, then the 2007 exhibition 《Energy》 (Hanmi Museum of Photography), held after another five-year

interval, presents a striking shift. Unlike his earlier works, in which people

appeared in most images, these photographs feature landscapes alone.

《Energy》 reaffirms Lee as an awakened

intellect who sharply distinguishes between lived reality and the reality of

landscape, while still knowing how to allow them to communicate with warmth.

His transparent consciousness becomes a site where crises inherent in life—embedded

within the grace of nature—are confessed and reflected upon.

The position of

“photographer as medium” seen in ‘Conflict and Reaction’ takes a more

abstract leap here: Lee becomes an agent who stirs countless winds to connect

the ground he stands upon with the sky above, enabling two worlds to call to

and respond to one another. This is possible because he embraces nature as it

is and loves and contains all living things, possessing an expansive surface of

compassion. One can sense this simply by looking at the enormous scale of his

prints.

The forests, trees, flowers, and waters depicted in 《Energy》 are the sources of life and the

principles of the universe. Though he constantly longs to leap, fly, and

transcend, what he ultimately seeks is life itself. Thus, Lee repeatedly

departs from the site of life only to return lightly once more. The hollow yet

resonant spaces that frequently appear in his photographs are spaces of

ceaseless motion—like the wind—and spaces prepared so that viewers may easily

enter and depart.

It is said that he spent more than half of each month

traveling to create these spaces; for Lee, seventy percent of life was

photography, and of that, eighty percent was time spent on the road, with the

remainder in the darkroom. Working selflessly according to what his own nature

loved, he arrived at a state of mu-nyeom (no-mind). Playing so

joyfully that work and play became indistinguishable, he found himself having

practiced photography for over thirty years.

Between

You and Me: Land of Others

“Photography

became more difficult the more I did it. The moment I felt I understood it even

a little, it became all the more overwhelming and painful. That is because the

era I live in, this reality itself, is that way. What is ‘life,’ and what is

the ‘reality of an era’? … Aren’t we all wanderers who have lost our way,

coming and going on ‘someone else’s land’?”

These

words appear in Lee Gapchul’s first photobook Land of Others,

of which only a single copy remains in the artist’s possession. The year 1988

was a special one—not only for Lee but for Korean society as a whole. Values

and orientations once taken as self-evident in Korean photography began to

collapse, while new technologies flooded in on the level of photographic

hardware.

Following the aggressive developmental policies of the Park Chung-hee

regime in the 1960s and 1970s and the economic push under Chun Doo-hwan in the

1980s, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the reorganization of a

U.S.-centered global order, and the hosting of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Korea

emerged from the periphery toward a liminal position near the center. Hybrid

times—neither center nor margin—began. It is no coincidence that questions of

“identity” surfaced as major aesthetic and social issues in the art world

around this time.

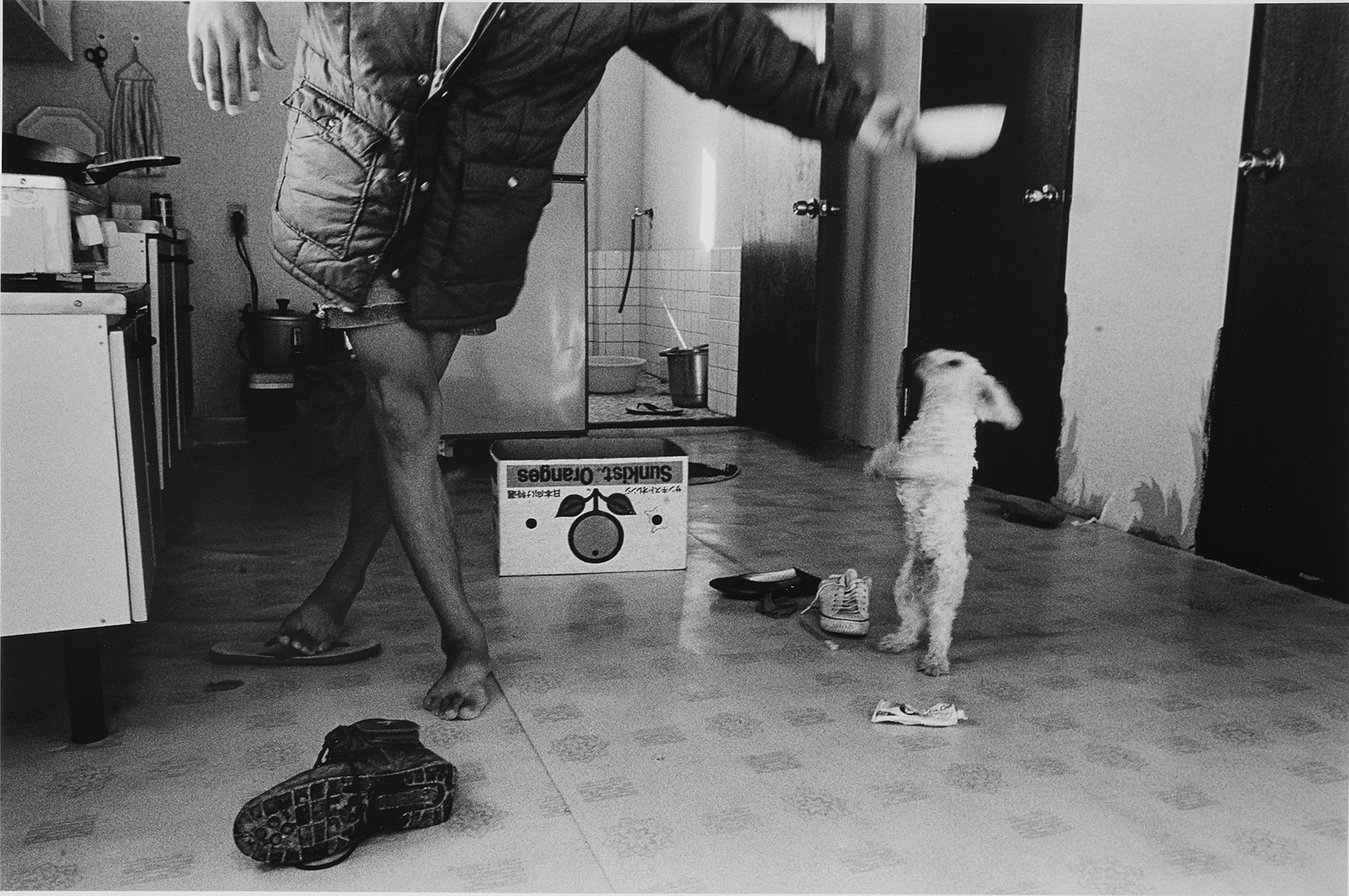

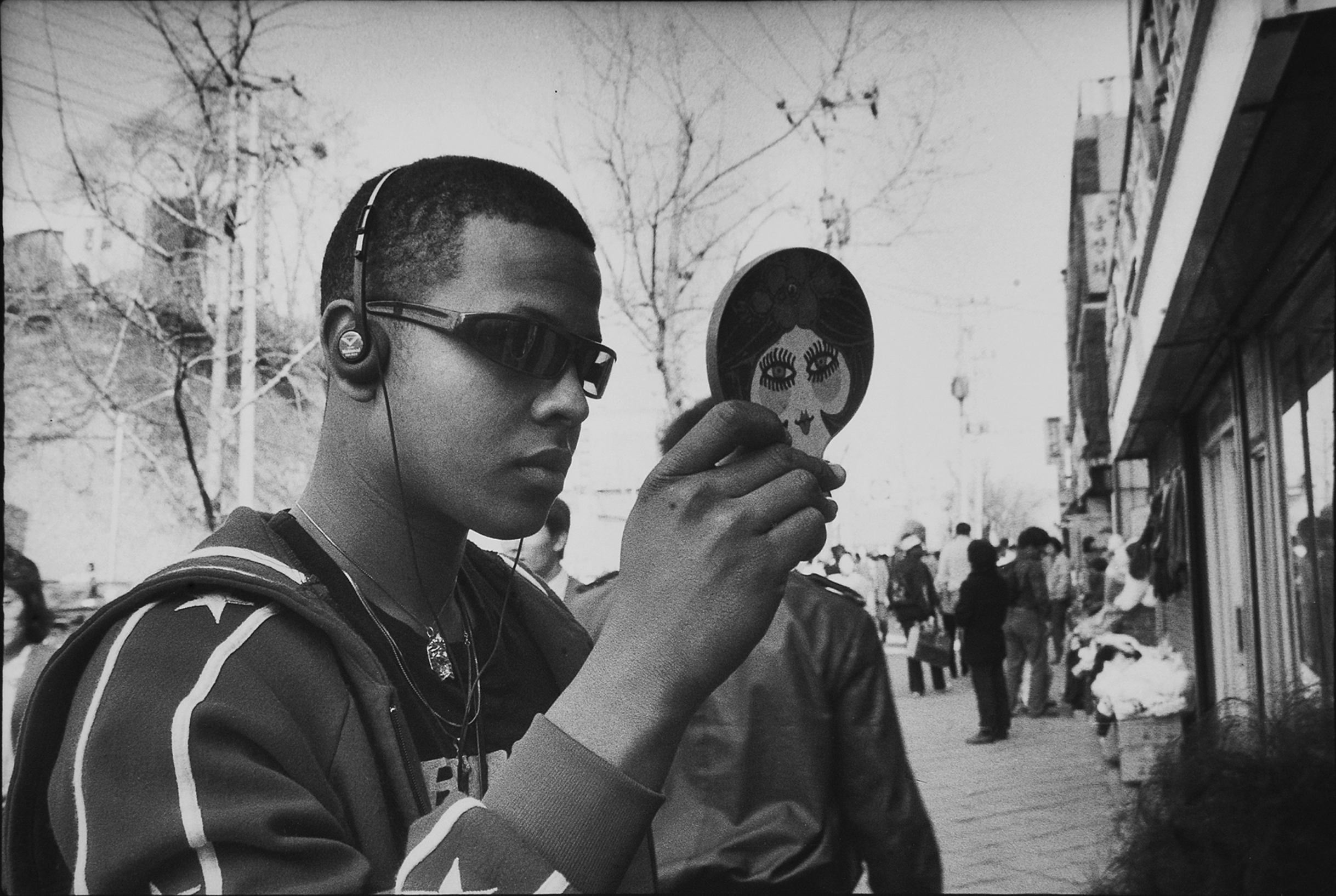

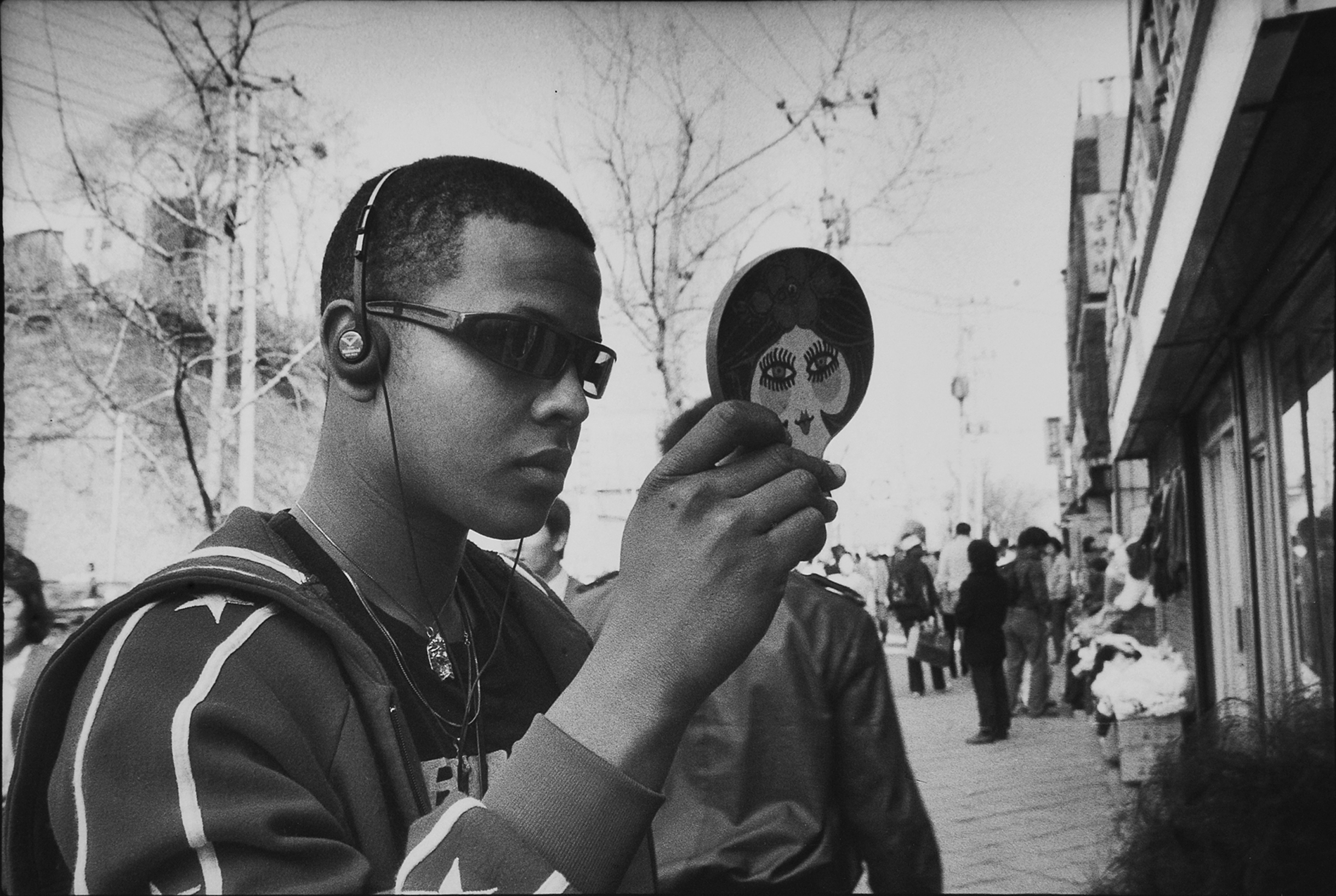

Lee,

who spent his twenties in the 1980s, persistently explored the people of that

era as his subject. Yankees on the Street, Images

of the City, and Land of Others are

works through which Lee, living in the 1980s, delved deeply into fundamental

and essential questions of life alongside the concrete realities of “here and

now.”

At the same time, these works carry a meta-level reflection on

photography, the photographer, and the photographic image itself. Consequently,

his early photographs are highly symbolic, acquiring depth proportional to

their symbolism. Armed with the intensity of unfamiliar forms and imaginative

vision, Lee probed the tension between self and world.

This

exploration of identity deepens and becomes more refined from Yankees

on the Street to Land of Others.

In Land of Others, a narrative unfolds through

compelling images that depict how individuals bearing inner wounds overcome

them and reclaim their sense of self. The concept of identity inevitably raises

questions about the relationship between what it denotes and what it

represents. Whether personal or collective, conceptual or material,

investigating identity requires first examining how it has been constructed.

Lee’s remark—“Photography becomes difficult and overwhelming because this era

itself is that way”—appears in Land of Others through

anonymous figures seen from behind, through shadows and silhouettes, faintly

revealed. The “others” Lee encountered emerge as incomprehensible, trembling

images at a distance. Thus, the photographer’s position—as an outsider even to

them—becomes crucial. His position mirrors that of the viewer, who encounters

their own unfamiliar core through the photographic other, continually asked who

they are and what they cannot endure. Ultimately, however, we—clinging to

incomprehensible situations and identities—are all incomplete beings, appearing

even to the photographer as unknowable.

Lee

laid down dark, thick expanses of solitude and loneliness as a method of

questioning that disrupts the trajectory of everyday life. Recognizing these

expanses as gaps of solitude and absence will help in reading Lee’s later

photography. Land of Others occupies an

exceptional position in the history of Korean contemporary photography, as a

major work that persistently examines subjects encountered on unfamiliar ground

and uniquely embodies them through a deconstructive photographic language. The series

was produced over two years, shooting approximately twenty rolls of film per

month, and is organized into 500 rolls of film along with work prints made on

now-discontinued Apollo photographic paper.

Photographic

Abstraction: Conflict and Reaction

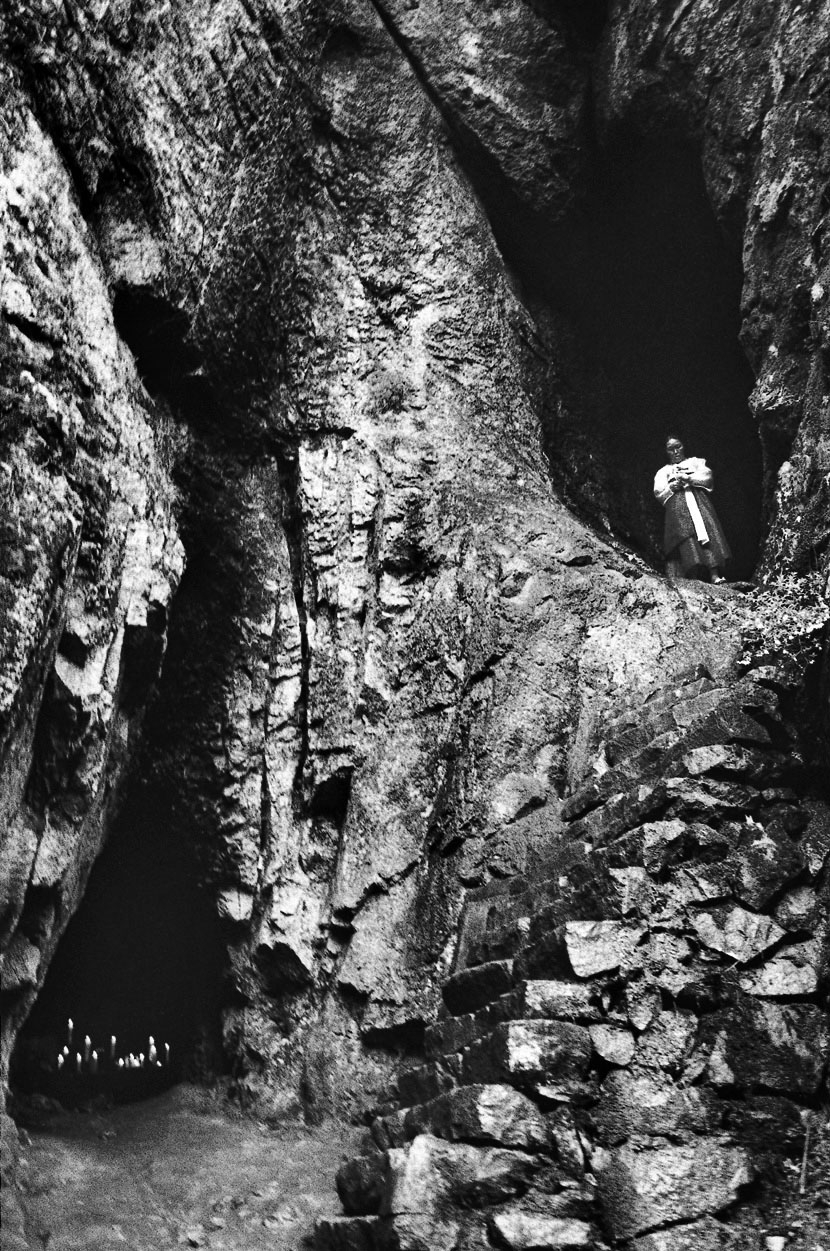

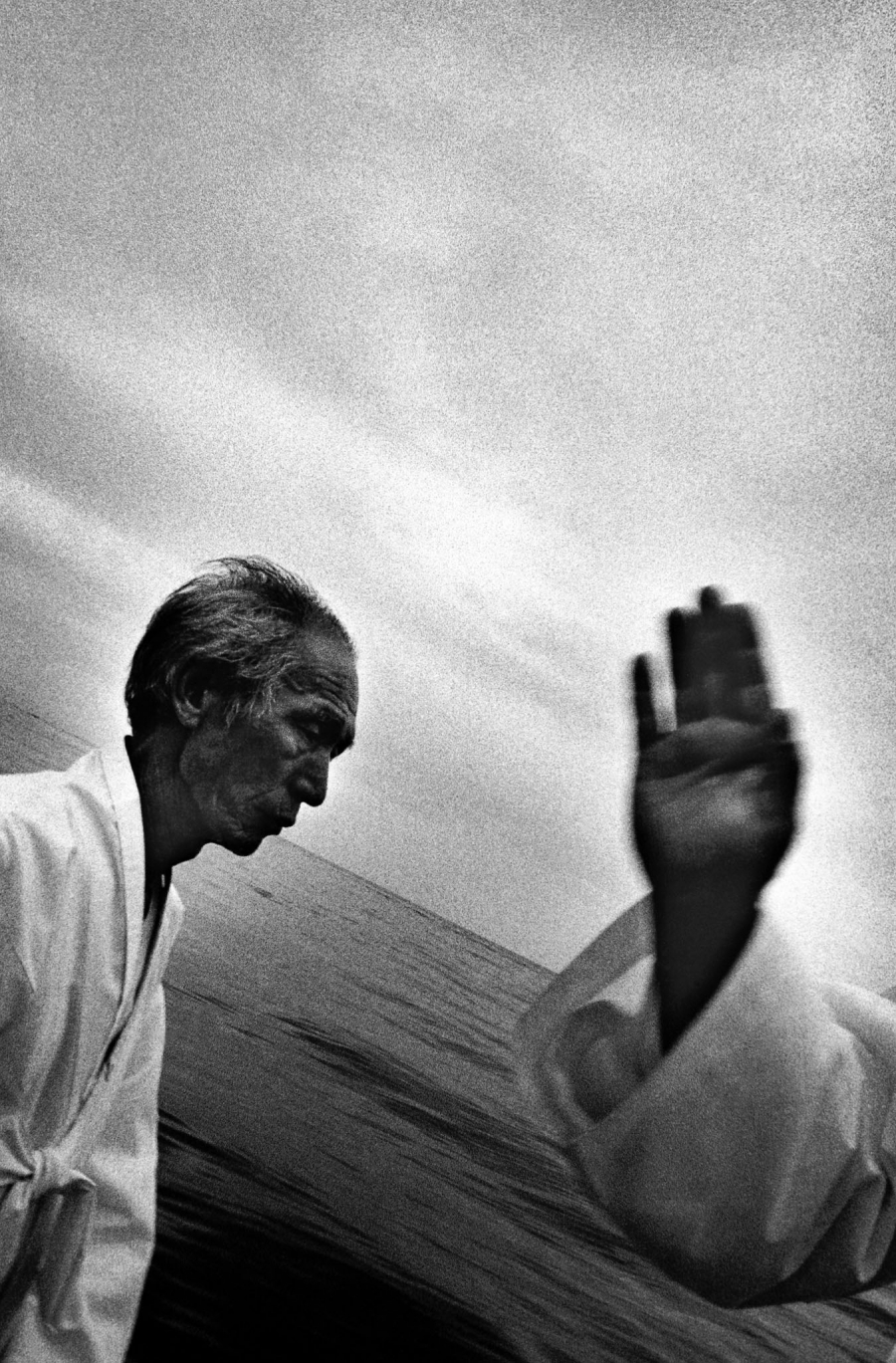

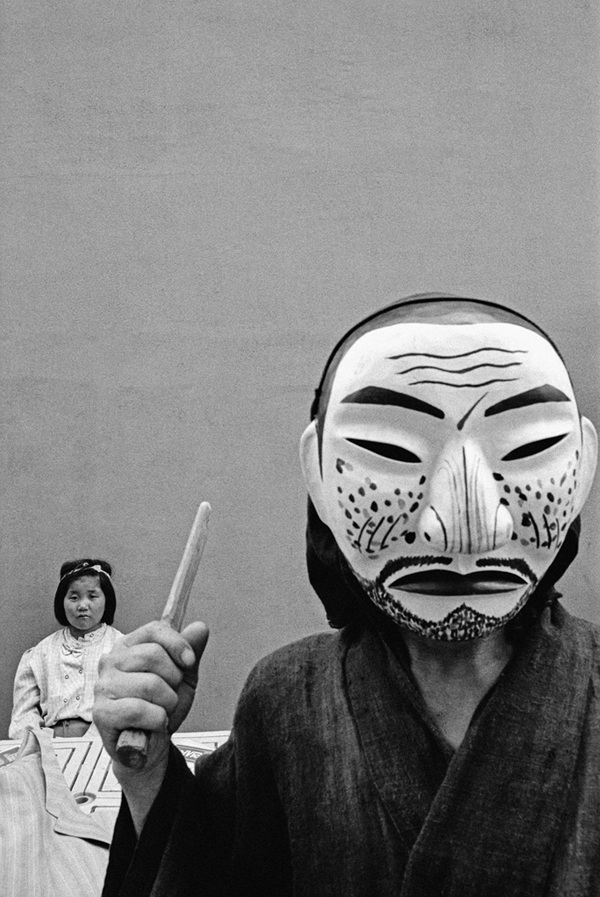

Conflict

and Reaction comprises works produced over eleven years, from

1990 to 2001, documenting ancestral rites, shamanistic rituals (including

fishing rites and the Wido Dragon King ritual), seasonal customs, folk games,

Buddhist ceremonies, and rural life. Andong, Namwon, Jindo, Gyeongju, Hadong,

Ganghwa—without drawing rigid boundaries, Lee captured the vast terrain of

uniquely Korean han across the land. Published alongside the

exhibition, the photobook Conflict and Reaction became

a monumental work, unfolding subtle energies between wounds and scars, this

world and the next, nature and mystery, abundance and peace, past and present,

present and future.

Many

still remember the taut tension that enveloped the Korean photography scene

when ‘Conflict and Reaction’ was first exhibited. “Shock” was the

only word that seemed adequate. Poet Kim Yong-taek remarked that Lee’s

photographs feel like “being struck on the back of the head,” while also

describing them as possessing a spell that “makes the world unfamiliar

again—makes us see it anew.” Christian Caujolle, director of the Paris-based

agency and gallery VU, to which Lee later belonged, praised the works as photographs

in which “Korean sensibility is expressed in a distinctive and liberated

manner.”

Although

these photographs construct narratives through minimal textual

information—titles that objectively indicate place and time—their strength lies

in revealing the artist’s subjective vision, emphasizing the dynamism of what

appears still. Text assumes photography’s evidentiary role, while the images

themselves expose meanings that are heterogeneous and dynamically in formation.

Documentary photography’s inevitable obligation to record can restrict creative

possibility, but the essence of photography lies beyond direct representation,

approaching abstraction and symbolism. This is why Lee ceases to “tell stories”

and instead leaves meaning to the viewer, allowing things to be “revealed.”

Rather than cutting and assembling time to generate dramatic meaning, he

reveals pure time itself. For Lee, “waiting” is more apt than “capturing.”

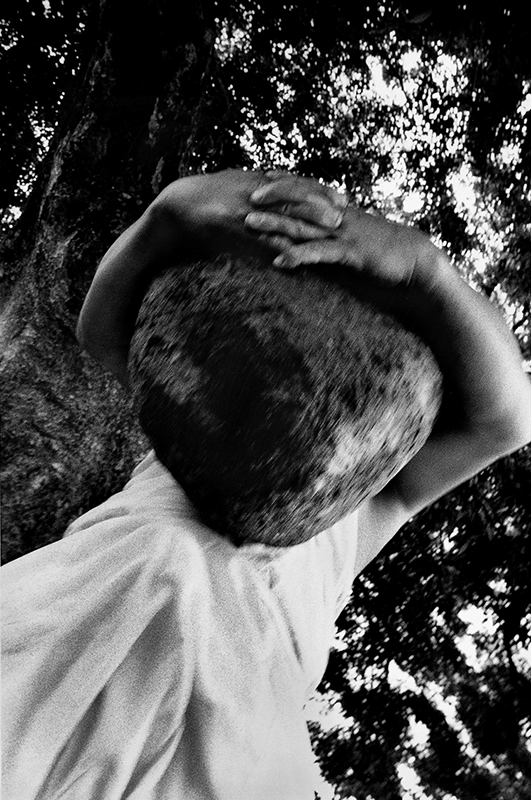

One

defining characteristic of Lee’s photography is its ability to bind together

things that appear distant and heterogeneous. He erases differences between

objects and perceptions, forging connections beyond and beneath opposition. As

a result, he lingers longer before the wounded, fragile, struggling, and

pitiable than before the healthy and bright. Becoming wind himself, freely

crossing boundaries, he nevertheless cannot pass by decay, pain, or loneliness.

This is evident in works such as A Child in White Clothing at a

Fishing Rite (Anmyeon, 1992) or Two Old Men in the

Forest (Namhae, 1994), where figures who seem to have traversed

both this world and the next appear uncertain and anxious. Compassion for

living beings becomes a condition for seeing both the depths and distances of

life, a source of imagination that pierces surface and underside alike. This

aligns with hwagwang dongjin—the coexistence of light and dust—akin to

Wonhyo’s philosophy of reconciliation.

Photography

is not the essence of things but the reflected image of things touched by

light. Where there is light, there is shadow; thus, all oppositions exist only

because “I” and “you” exist together. Lee’s photographs therefore require no

analytical justification; they form concrete masses of imagery. Their core lies

in an imagination that binds opposites—vertical and horizontal, essence and

phenomenon, life and death. This imagination becomes possible only when one

opens oneself fully, filled with boundless compassion and love for the world.

Thus, viewers are left defenseless, infected by the photographer’s

imagination—which Lee himself calls the unconscious—and this imagination

constitutes the trajectory of his work.

Lee’s

photographs demand repeated viewing—sometimes singly, sometimes as a whole.

Only then do the spaces of silence and absence he selects become visible, and

one can sense how images collide, resonate, and converse within sequences to

generate new meanings. Photography grants the living confirmation of both

“presence” and “absence.” To overcome absence, people photograph, speak, and

perform rituals of consolation. The photographer recalls moments etched in

memory back into the here and now.

The empty spaces in Lee’s photographs are

spaces of memory—spaces of the dead, spaces without time. As a medium, the

photographer summons vanished spirits, restores relationships between the

living and the dead, and generates the “frame”—the boundary between living and

disappearing. For Lee, the frame is not merely a device of selection and

exclusion but a site for the emergence of punctum, where inside and

outside connect seamlessly.

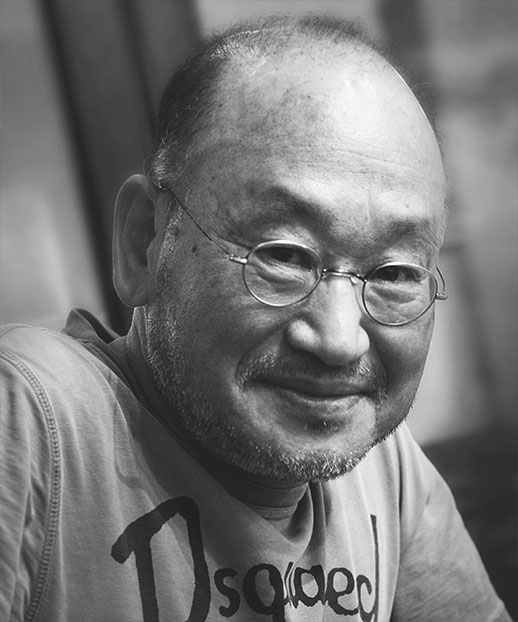

Revisit

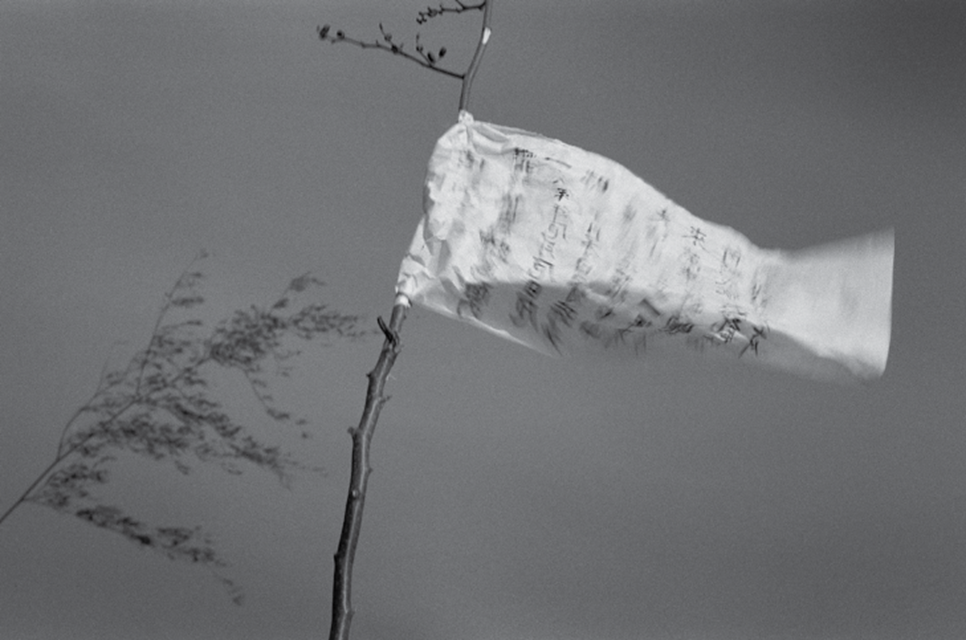

the stillness that breathes within his constantly moving images. Birds take

flight, people sway, flags flutter, clouds and birds skim mountains. Children

seen from behind gaze at crooked mountains with flowers on their heads; along

the ridge of Geumsan in Namhae, a child weeps. As if foreseeing the later

tragedy of the Taean coast, a shaman descends a hill drenched in animal blood

(red rendered as black in monochrome).

Two old men confront one another in a

forest. The empty spaces recurring throughout these images are filled with

dense absence. After repeated cycles of improvisation, deviation, dissolution,

and recomposition, the final page of Conflict and Reaction shows

kites vanishing stubbornly toward a single vanishing point, carried by the

wind.

Viewers imagine piercing a hole in their hearts through which that wind

passes. And just when it seems finished, the next page reveals an old man

passing through a low doorway. As Jung Jaesuk observed, it is the trembling

“reaction” unconsciously shown by people in moments of “collision” that gives

Lee the force to press the shutter.

Moments

of life embedded in concrete experience and their sensory mysteries can never

be expressed through conventional forms. In ‘Conflict and Reaction’, Lee

dismantles long-preserved photographic conventions, boldly experimenting with a

new grammar of photography. This may be the indispensable condition that

photography has required to sustain itself as a modern medium—its fundamental

force. Through photographers capable of capturing the world’s rich actuality,

photography has acquired the value not of fact, but of imagination and

abstraction.

A

Love Letter to the Landscape: Energy

I

once asked the artist about the exhibition title ‘Energy’. My objection

was that the title felt too direct—perhaps because it echoed titles long

familiar from salon photography, provoking a contrarian resistance. His

response was simple. “Isn’t photography like poetry? I don’t think with my

head—I just photograph moments that I feel. To fully savor moments of life:

photography grants us that power.”

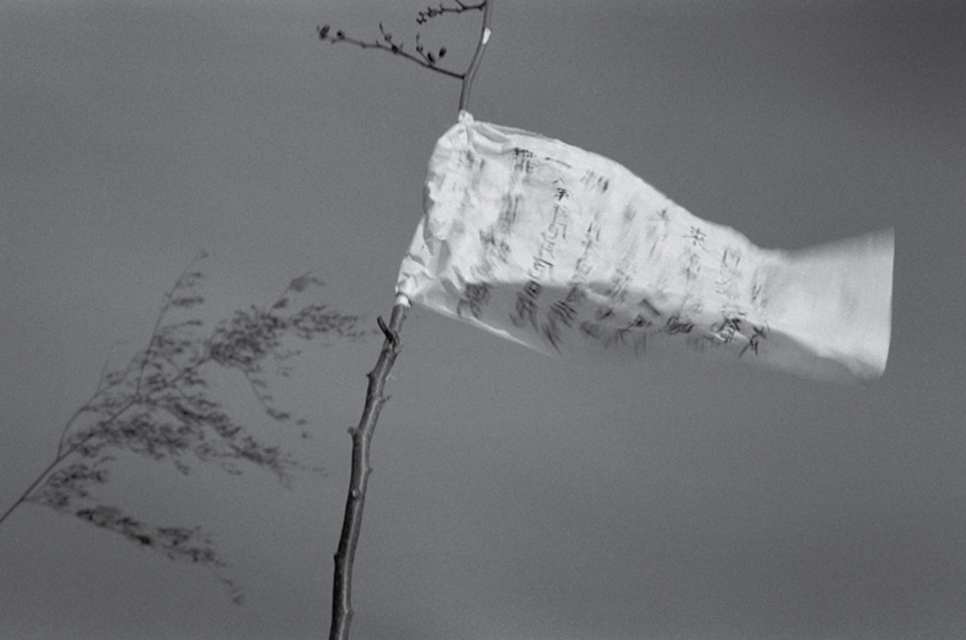

If

Lee Gapchul once interpreted reality, the Lee of today interprets landscape.

His talent—and what makes the photographs in Energy exceptional—lies

in extracting and refining deeply intimate moments from subjects we have long

looked at absentmindedly, as if they were loving one another. To distill the

essence of landscape, Lee approached swiftly, observed slowly, and photographed

with a slow shutter. What emerges is the “time” of the landscape itself.

Between the front and rear shutters, physical changes of time—how people, love,

and mountains alter as time flows—linger and settle. In this way, while Lee

presses the shutter, the viewer’s emotions also grow denser. He captures the

wind moving in the spaces between shutters, between things. As this happens,

the artist’s inner energy gradually warms; the landscape itself ignites the

photographer. Perhaps that is why he called it gi.

Lee’s

landscapes do not aim to reveal total outlines or meticulous details. Instead,

they concentrate on expressing a dynamic atmosphere that is both bold and

delicate. This is because he sought not to fix a specific moment of landscape,

but to reveal the continuous movement and flow of scenery and objects as they

change moment by moment under light. Whereas Alfred Stieglitz pursued a state

of transcendence by quietly contemplating the world and seeking equivalence,

Lee opens his entire body to breathe with the landscape, stepping closer

through a telephoto lens to reach the world’s hidden truth. This differs from

his earlier work, which primarily used a 28mm wide-angle lens. He said it was

to show only the essence—because only then could the energy of the landscape be

conveyed.

As

Lee himself has said, “Traveling across this land, breathing in the scent of

the earth and receiving its energy is both joyful and heart-aching.” His

landscapes are thus clear lyricism, finely attuned to the artist. Even within

the same location, they reveal entirely different atmospheres depending on time

and environmental change. If wind blows in a photograph, then it truly was a

windy day, and one can hear the sound of that wind’s movement. In

particular, 2004, Hapcheon expresses a state of

profound immersion in landscape.

Likewise, the dusk, trees, and birds perched

atop branches in 2004, Jangsu cohere into the

totality of landscape, each subject fully inhabiting its own individuality—like

winter trees loosely spaced, each facing its own sky, whose interstitial

tensions gather into a collective choreography.

The

“photographic moment” in Lee’s work is never something that can be routinized;

the fullness of the present he experiences within landscape passes in an

instant. With quiet restraint, he offers viewers cherry blossoms trembling

brightly in sunlight in 2004, Hadong, and flowing water

in 2005, Sancheong, creating symbols of landscape

imbued with a liberated innocence freed from pain and anguish. What, then, does

it mean to take photographs? Lee’s work unexpectedly poses this fundamental

question.

When

the question shifts to whether a photographer can create nature—or is doomed to

merely imitate it—the answer becomes relatively clear. Much landscape

photography has operated under the belief that photographers can “make” nature,

or has unconsciously followed that logic. Since Ansel Adams, it has been

axiomatic that beautiful nature and photographs of it inherently acquire

aesthetic value.

Against a climate that produces landscape photographs with

superficial splendor and unreflective arrogance, Lee’s landscapes offer a

response. His photographs allow us to encounter landscape through subtle

tremors. That is why the sound of wind passing through bamboo groves in 2004,

Damyang feels all the more poignant.

Mother!

Lately,

I have been photographing the landscapes of our country—not simply beautiful

scenes, but landscapes that chill my heart. The faint landscapes of my

ancestors’ youth, of my parents’ youth, and of my own childhood.

When pale pink azaleas bloom on the low mountain behind my home in spring; when

the green oak forest shaken by summer rain regains its color; when lonely

whispers of reeds are heard in autumn fields; when sleet drifts through deep

mountains in winter—nothing could be more beautiful.

The sound of a stream, the

call of a cuckoo from the back hill, even clouds reflected in rice paddies at

dusk—all arrive as heart-achingly beautiful landscapes. They were even more

precious because my mother’s image was always reflected within them. As another

day ends, the moon has risen over this plateau. My mother’s name was Wol-im (月任). Seeing her face, once like white wild roses, emerge within the

moon, I quietly recite this poem.

Deep

into the black night, Mother comes alone,

Her white ankles hurrying toward me.

Each night, the dream I see is the dream of my white mother,

A trembling dream beyond the mountain ridge.

(Lee Gapchul, from “To My Ever-Missed Mother”)

As

I carefully examined Lee Gapchul’s photobook Energy, I

experienced unexpected wonder and subtle emotion. Lee never tries to explain.

And indeed, how could a photographer explain the countless complex and delicate

phenomena of nature? He does not analyze his subjects; perhaps he leaves that

task to the viewer. His photographs speak to no one in particular—they simply

show the world as it is, and the movements between things. To those who can

read that movement, Lee becomes a truly wondrous photographer.

Unoccupied:

Emptiness Is Form

Lee

is said to conduct Zen dialogue with his camera. Though not a Buddhist, he

loves mountain temples and mountains, and listens to Buddhist chants he does

not fully understand while driving. His guiding question has now shifted

toward emptiness is form (空卽是色). The path of the mind that moves from possession to being is best

expressed through the Buddhist thought of form is emptiness, emptiness is

form.

Humanity, enslaved by possession, fails to participate in the productive

site of being and drifts into vain fantasy. Photography, in particular, has

long been narrated from the standpoint of possession—shooting, capturing,

framing, displaying, overcoming death, simulation, fixing. Such discourses

resist Buddhist interpretation. Emptiness, as Wonhyo wrote, is neither

attainable nor unattainable.

Photography, conceived as something that

“contains” reality, has stood at the center of possessive desire resisting

death. Can Lee articulate emptiness is form through photography? Even

the desire to express may itself be desire. Should one then stop taking

photographs?

Lee’s

answer is again simple: emptiness is form is not a dead void, but a

state of mind from which something endlessly wells up. Perhaps this ontological

desire to act for others through photography is what Lee means

by emptiness is form.

The

photographic spaces Lee creates are “illusory” spaces that once existed. They

draw out the substance of memories that may have vanished, allowing ephemeral

things to touch eternity. To view his photographs, one must let go of the self

to avoid missing the flow of rapturous landscape—because his images are filled

with subjects for whom “even a fleeting glance recalls countless past

connections, dissolving accumulated karma in tears.” These are things alive

now, yet destined to disappear. All of us are such beings.

To

those who doubt whether the beauty or power of his photographs bears any

relation to reality—who dismiss them as private confessions or image-play—his

work says nothing. It simply shows the world and the movements between things.

Thus, to those who can read that movement, Lee Gapchul reveals himself as a

truly extraordinary photographer.

What

will a photographer with a cosmic mind show us next? Will the calm of

self-benefit quietly transform into altruistic offering? That original vitality

already exists in Lee. He is not filled with himself; he is free and spacious.

Marcel called such a state “being unoccupied”—empty, yet always ready to

respond to a call, ready to be sensitized.