Beautiful

things overflow everywhere. Whether in painting or photography, everything is

uniformly polished and decorative. Added to this are countless works that

recycle long-dead Western specters from half a century ago, lazily attaching

the unfounded modifier “Korean.” This is the result of aligning art with

consumer taste and monetary pleasure—a distorted byproduct of a contemporary

art scene in which marketability itself becomes the aesthetic standard.

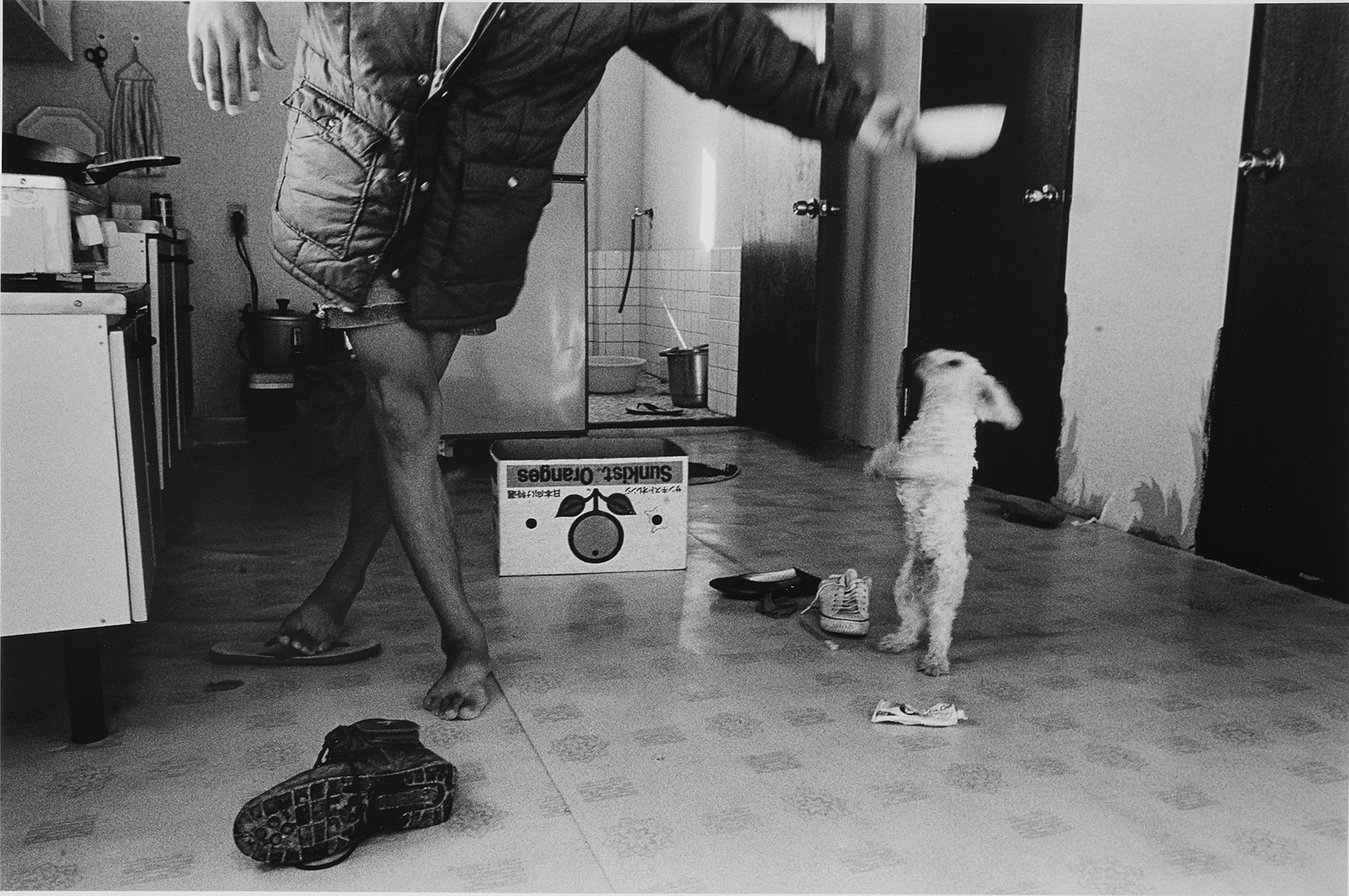

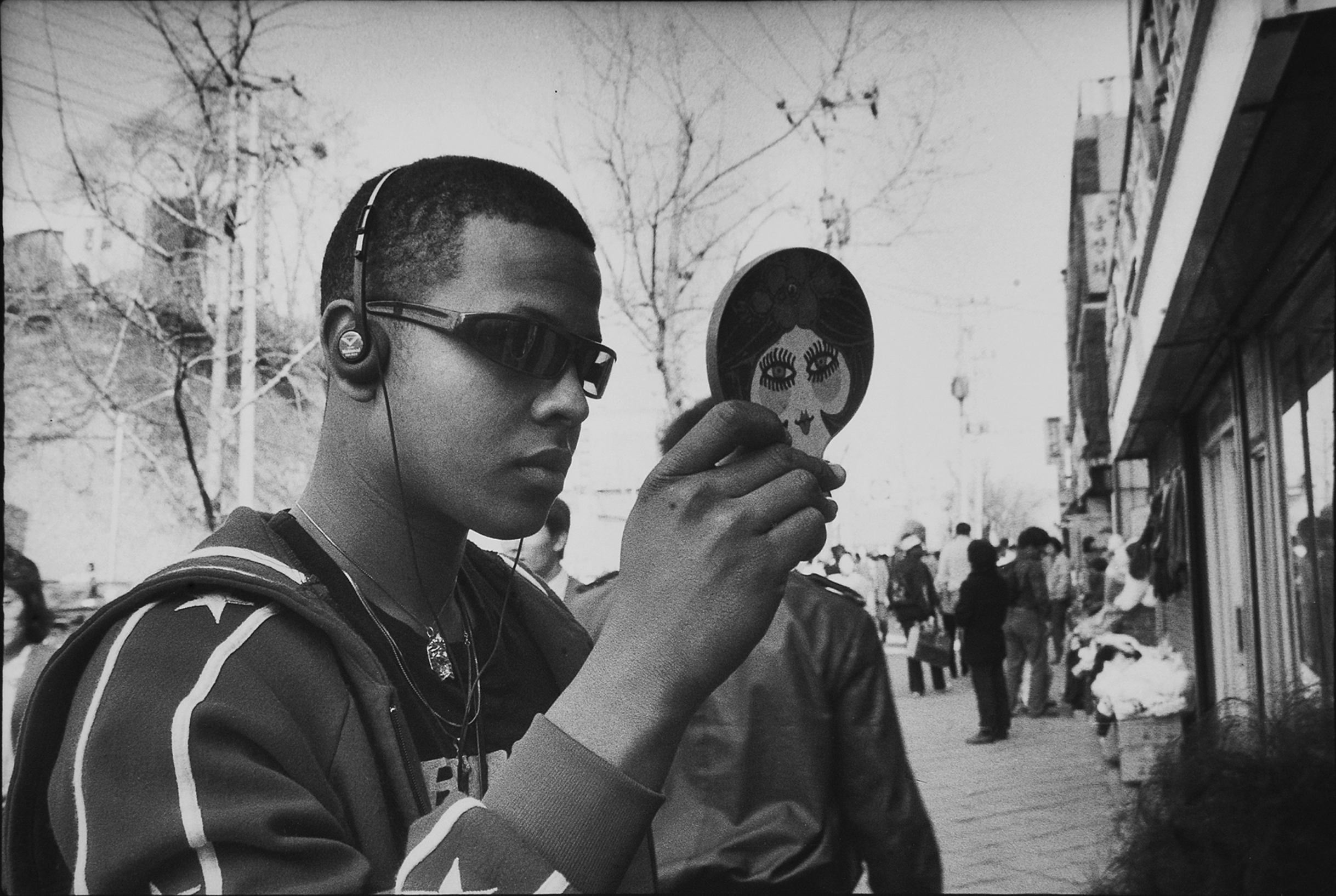

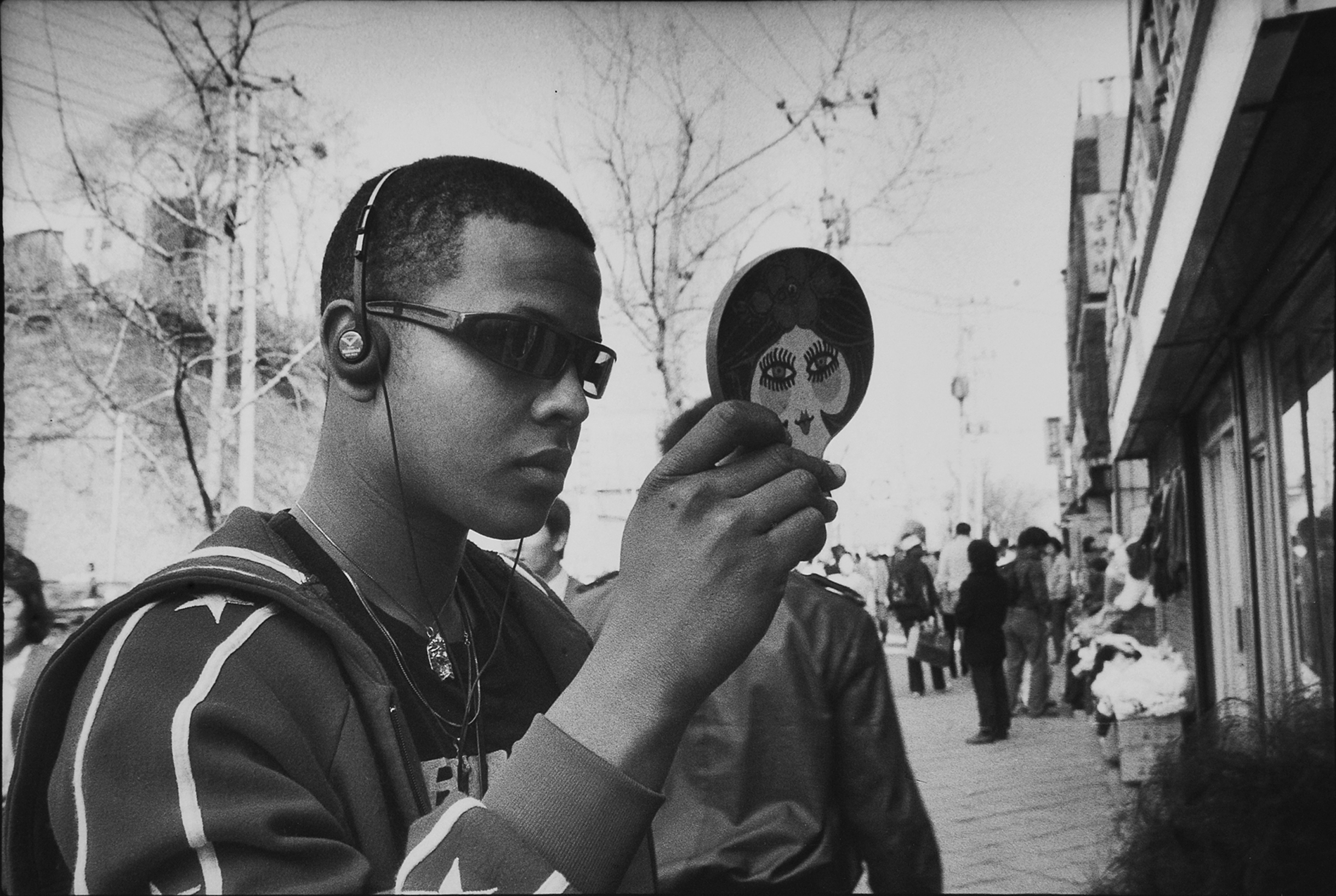

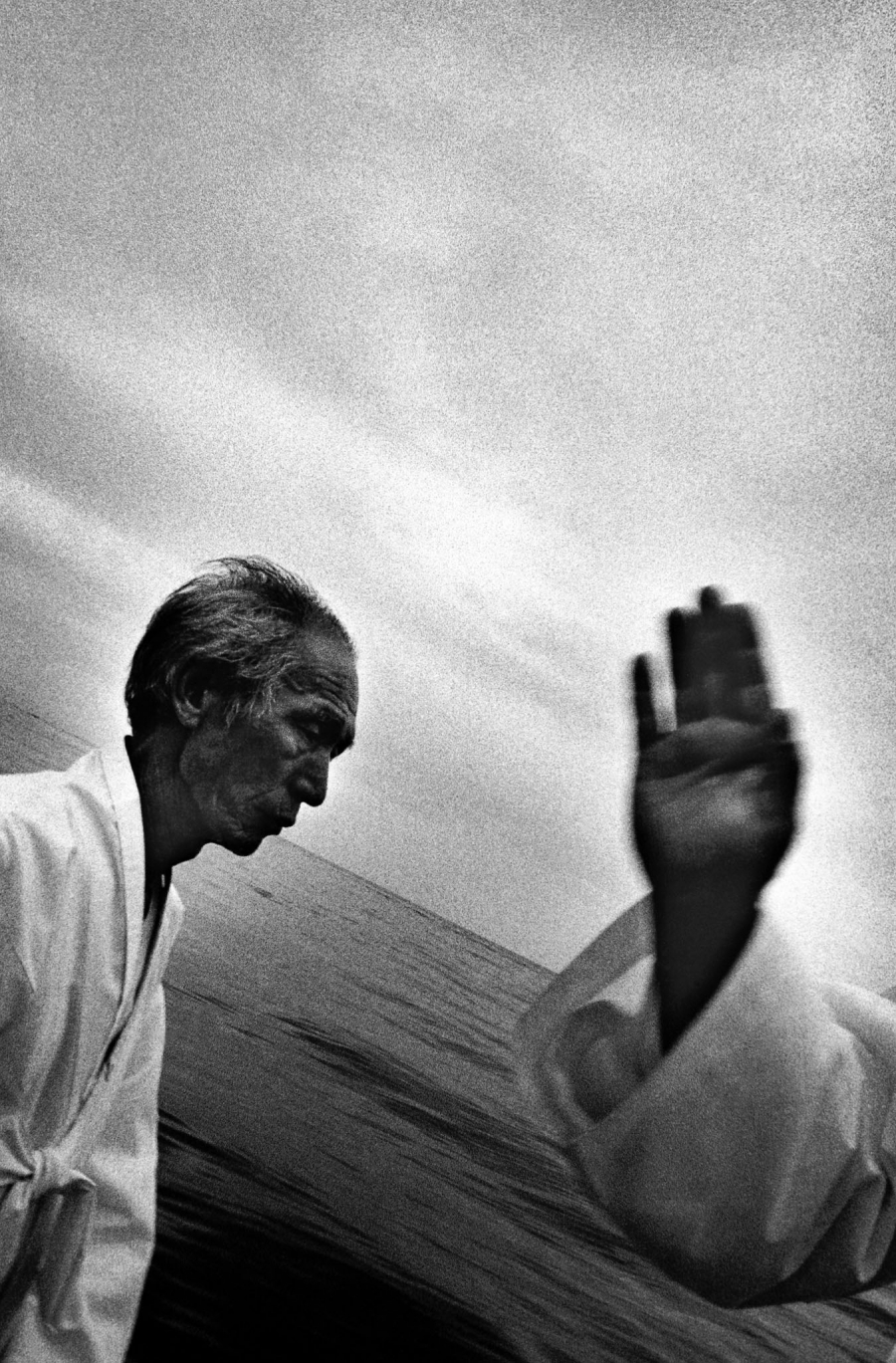

Lee

Gapchul’s black-and-white photographs are anything but pretty. They are somber

and rough, even forceful and unstable. Yet they are imbued with an inexplicable

energy and provoke a strange shudder. This is likely because they articulate,

in a factual visual language, the spirit and soul of Koreans layered deep

within the foundations of the nation, along with their spiritual atmosphere.

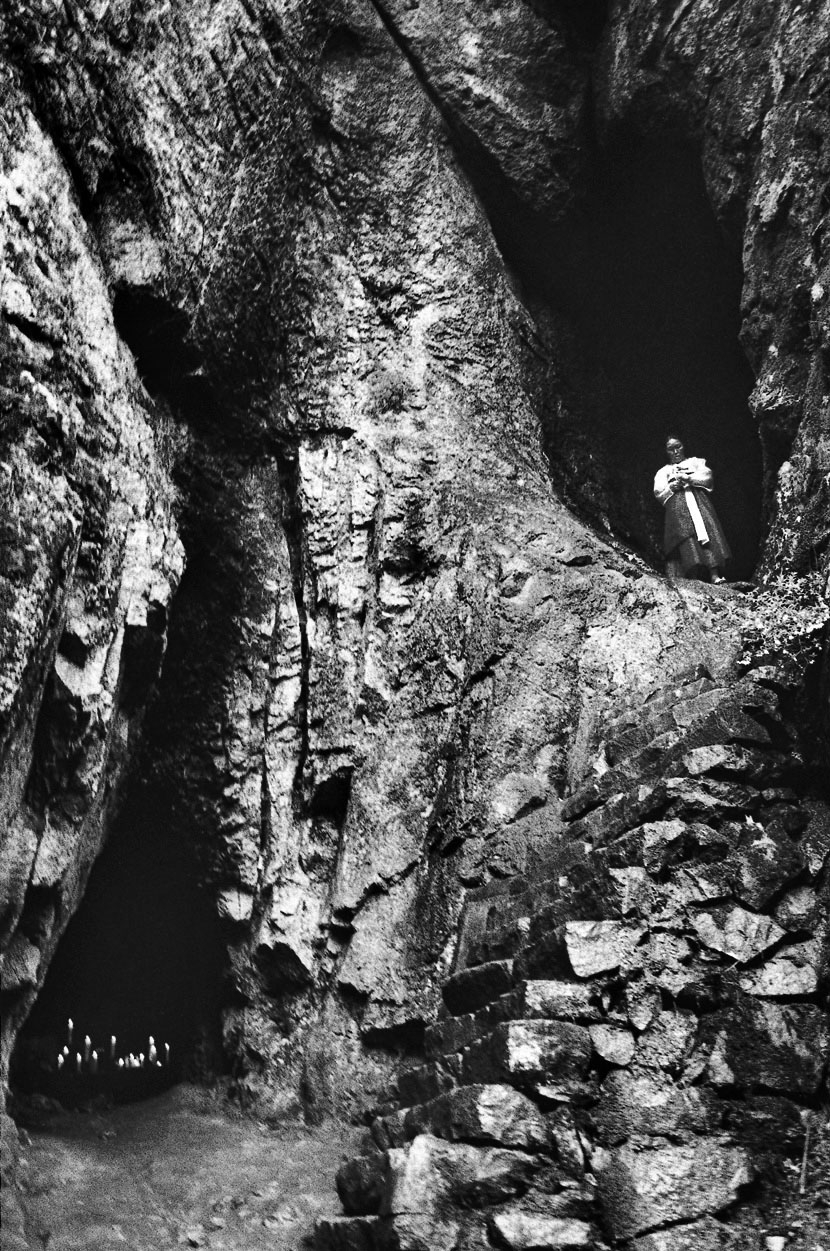

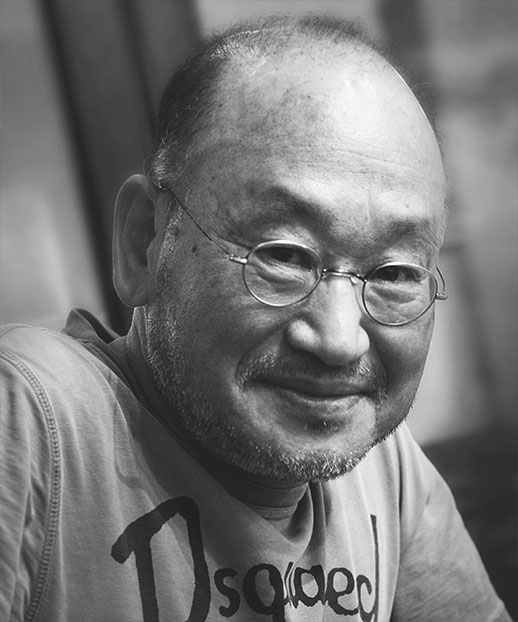

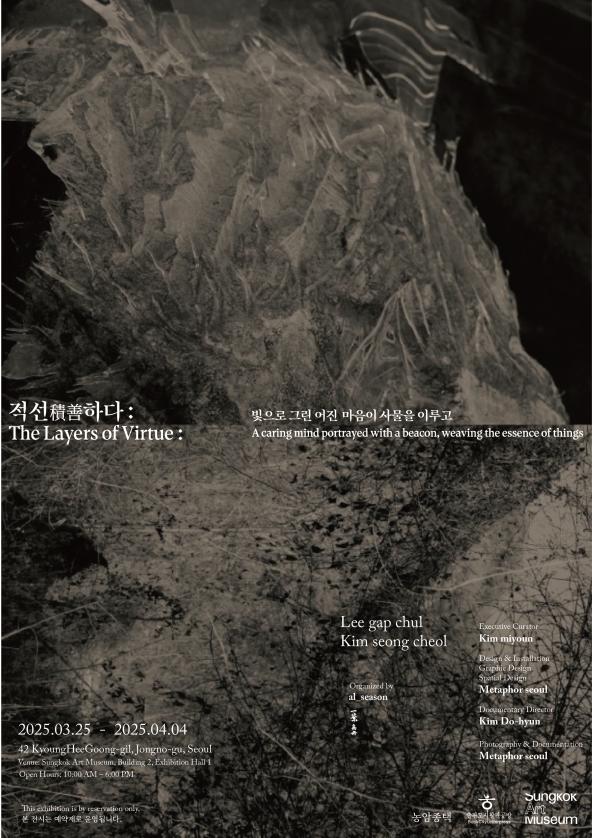

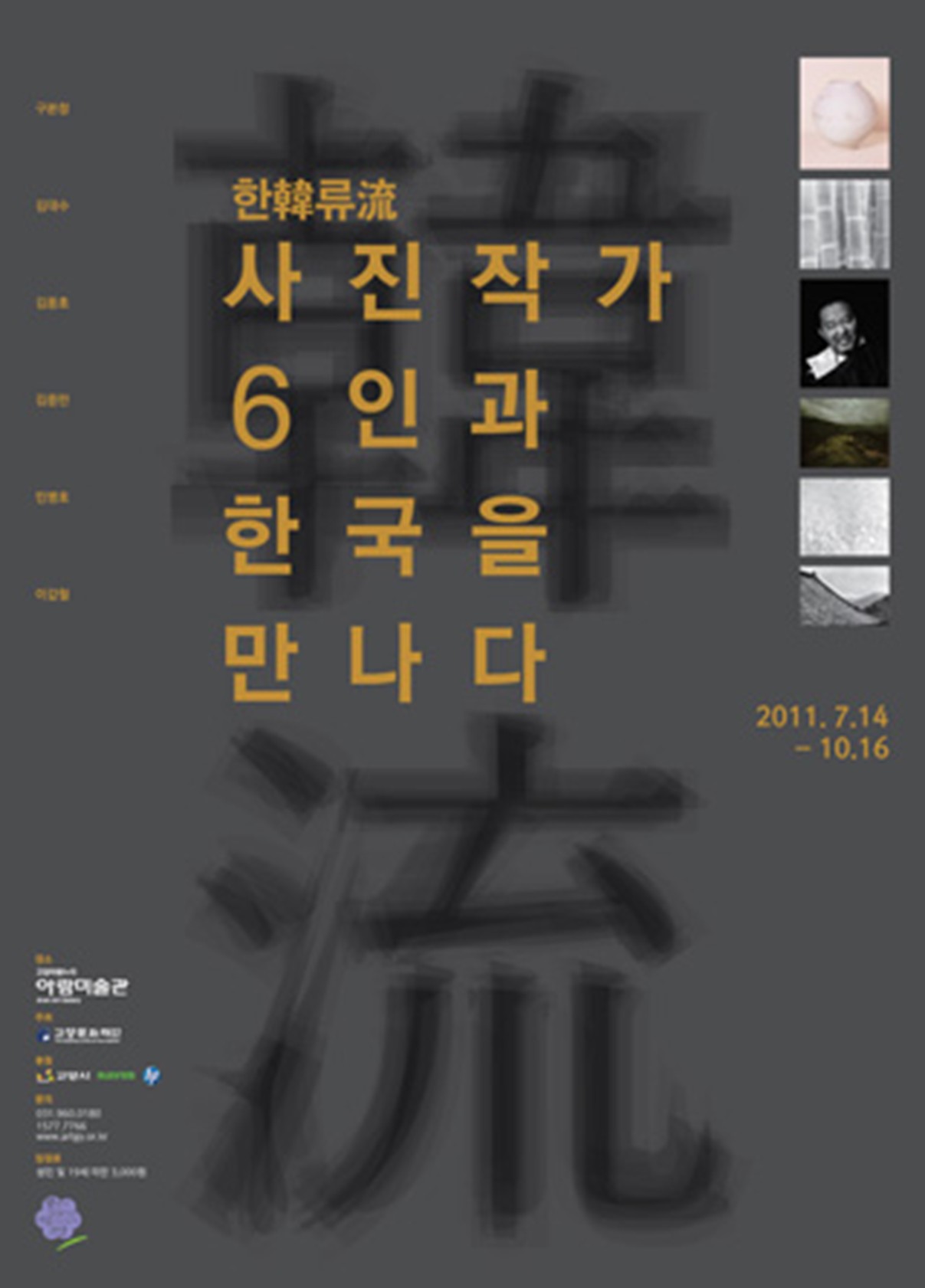

Lee

Gapchul sent shockwaves through the Korean photography world with his solo

exhibition 《Conflict and Reaction》 held at the Kumho Museum of Art in 2002, excavating Korean

sensibility and the unconscious. Through “decisive moments” that capture the

invisible yet undeniable human subconscious, he established a distinctive world

of his own. By persistently probing Korean identity, he was ultimately

recognized as having firmly stood on his own. In this sense, ‘Conflict and

Reaction’ marked a crucial turning point not only in the field of

photography but also in Lee’s personal artistic trajectory.

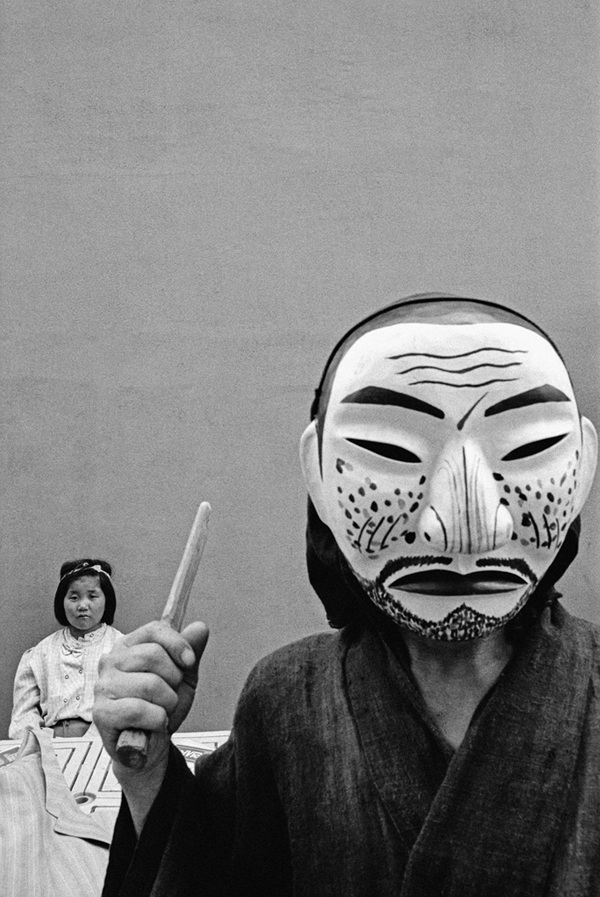

The

works presented in ‘Conflict and Reaction’ were, at first glance,

unmistakably photographs of Koreans taken by a Korean—images that captured

something closest to an original essence of “ours.” They went beyond mere

representation or documentation that confines visible subjects within a frame.

Rather, they resembled a kind of requiem that exhaled generations of inherited

sorrow and spirit, chanting the yin and yang of Korean life.

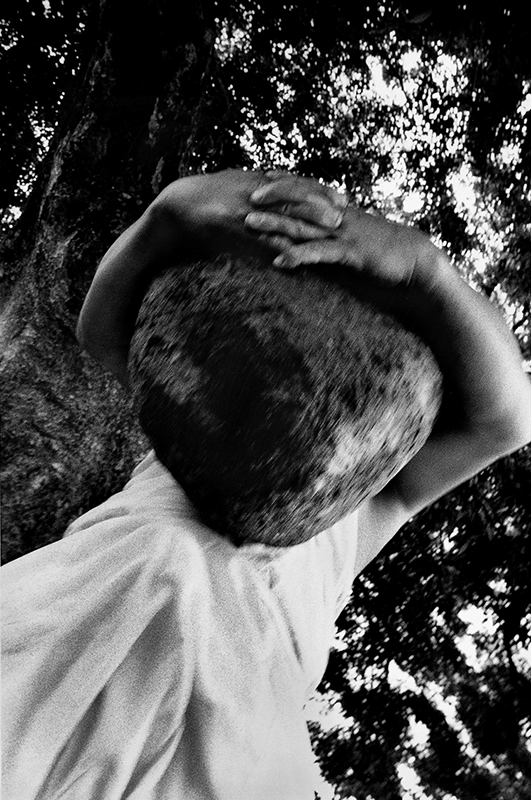

Representative

works include A Shaman with an Ox Head on Her Head (1992),

marked by strong primitivist and shamanistic tendencies, and Shaman (1992),

in which a blood-smeared shaman appears to slash through the world’s knots.

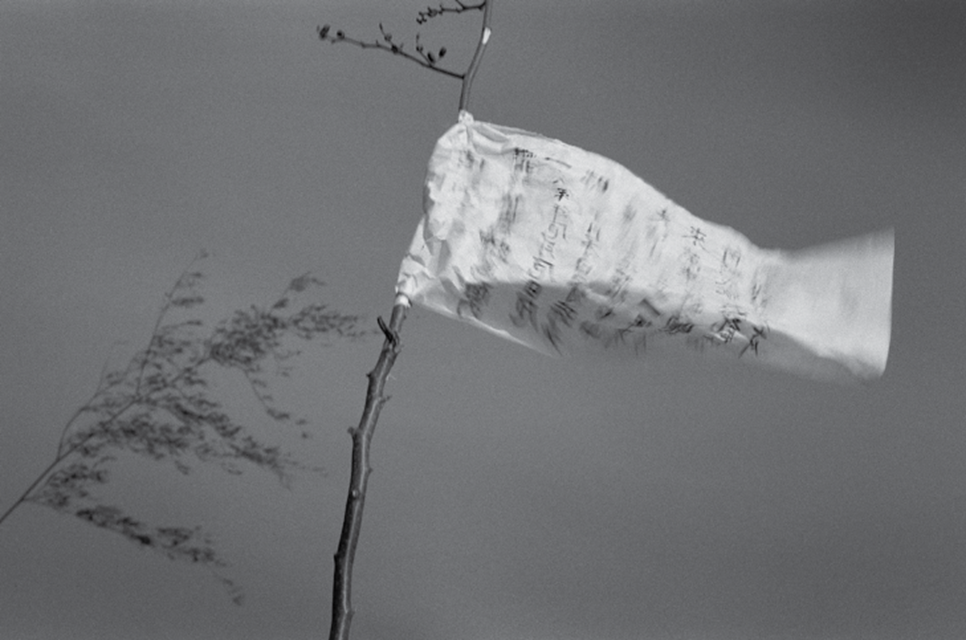

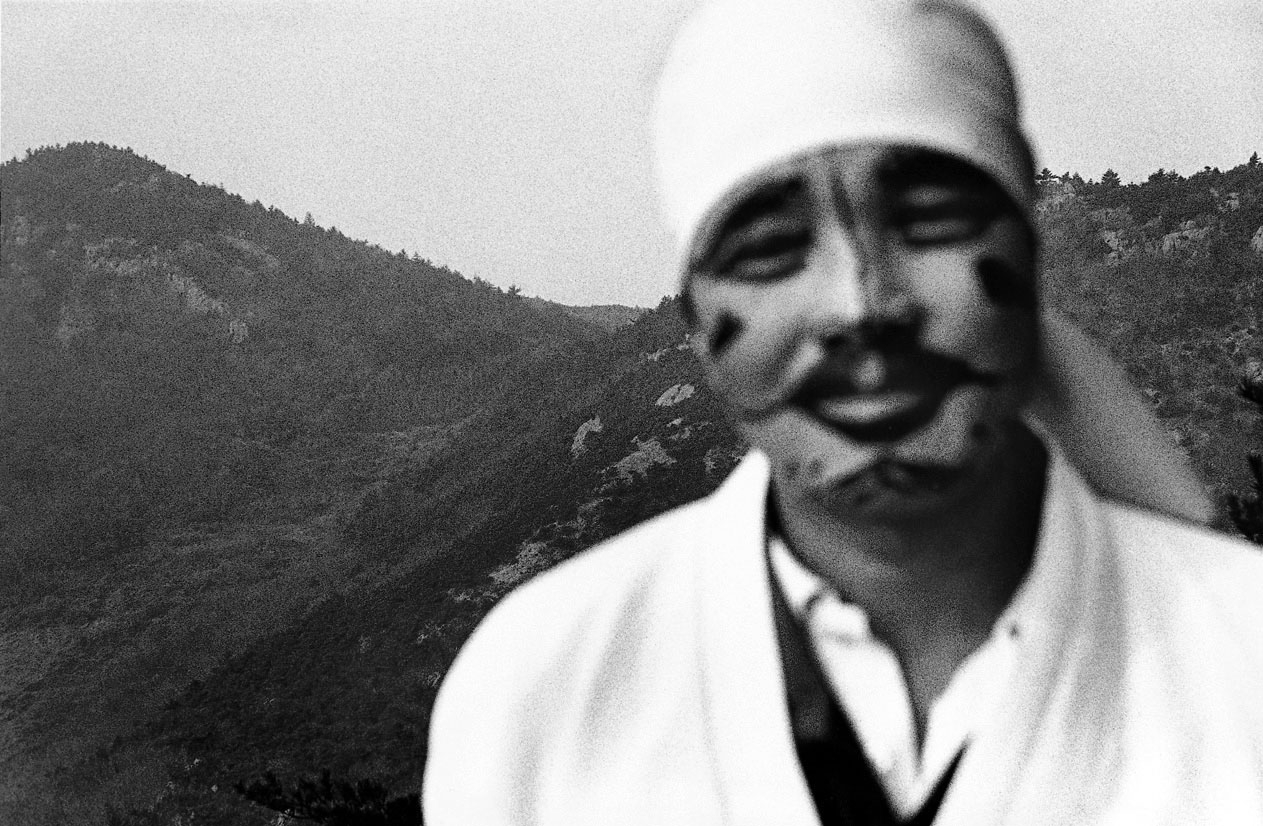

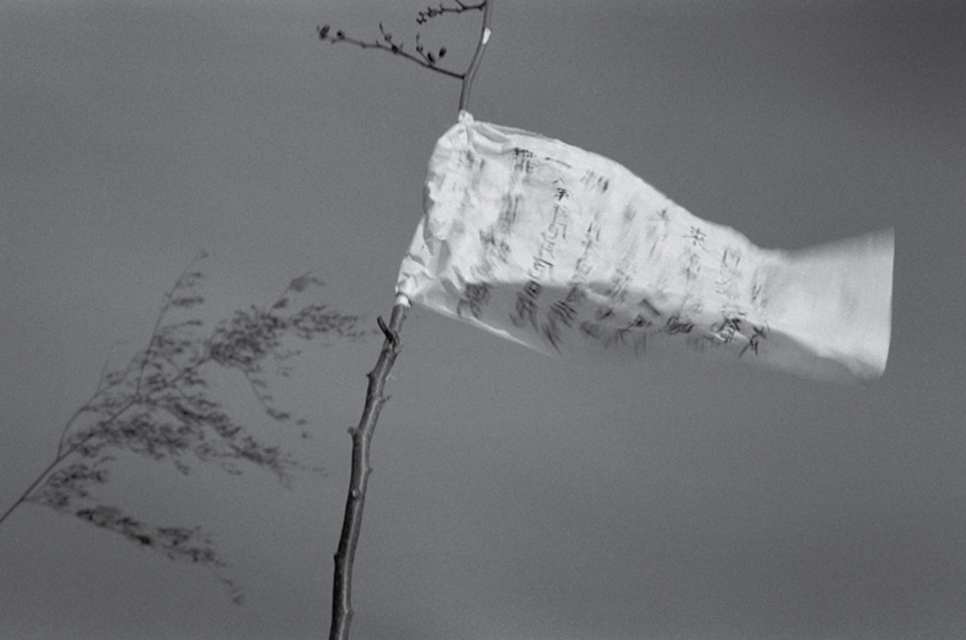

Dreaming

of Liberation–2 belongs to a foreshadowing of Lee’s later works,

which layer quiet resonance through refined visual language. The photograph was

taken during the cremation ceremony of Venerable Seongcheol, held in November

1993 at Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon.

On

that day, Gayasan Mountain and Haeinsa were filled with crowds, and the

ceremony proceeded solemnly. Many photographers focused on capturing every

detail of the event. Lee, however, perceived the lingering presence of the

great monk in the sky, the wind, and the trees. He read an indescribable energy

enveloping the temple in the quiet meditation of a single monk on a rooftop.

It

was silence, yet an extension of liberation—an escorting of the monk’s clear

and profound fragrance as it dispersed along the valleys of Gayasan, carried by

fire and smoke. Lee intuitively transferred this moment to his camera.

Contemplating the ultimate boundary of life and death as part of nature, he

rendered the lingering tenderness and ache behind Korean cultural tradition and

emotion through stillness and quietude.

After ‘Conflict

and Reaction’, which generated considerable resonance, Lee’s photographic

aesthetics deepened further. Themes such as life and death, existence and

anguish, soul and mind, reality and prayer gradually retreated beneath

nature—sky and earth, trees and grass, water and wind—where energy (gi)

permeating mountains and rivers across the country emerged as a new horizon for

documentary photography. This was clearly far removed from the polished

packaging typical of conventional photography. Though the subjects were Korean,

the content within was decisively different from works that merely appeared

Korean on the surface.