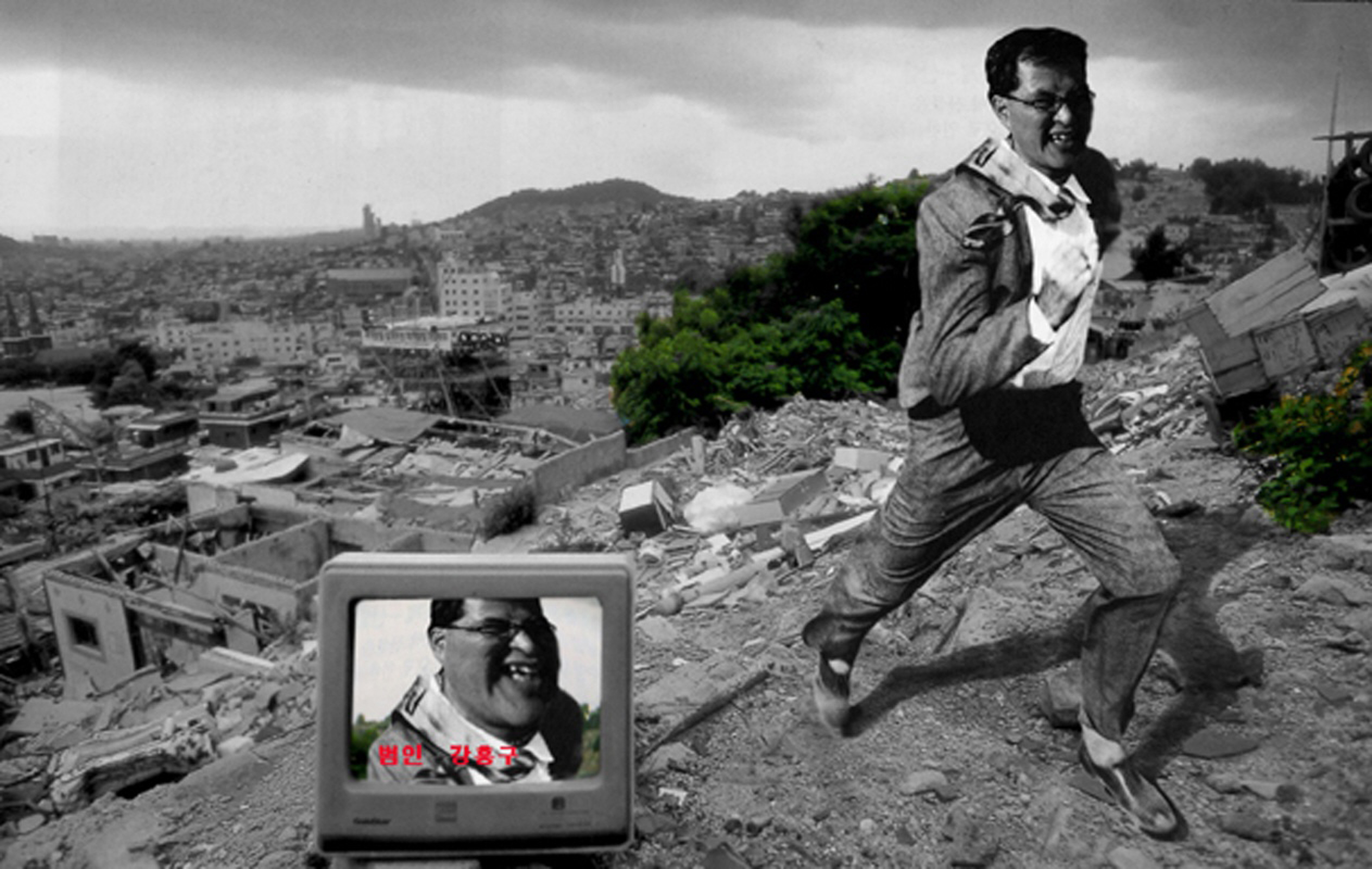

Kang

Hong-Goo’s works confront viewers with situations that feel incongruous and out

of place. They are awkward and unsettling, leaving the viewer at a loss as to

how they should be read or how they should be seen. In this way, Kang draws us

into his gaze and asks us to raise objections to reality itself.

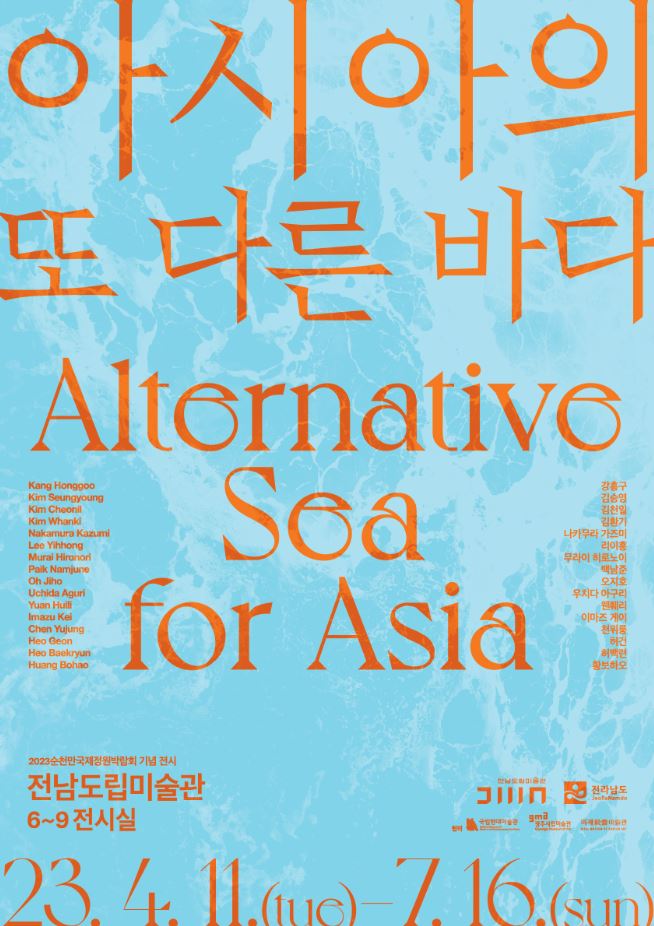

This

exhibition presents works produced between 2004 and 2010. It includes selected

pieces from the series Landscape of Osoe-ri, Mickey’s

House, Trainee, Vanish Away,

and The House. It is an exhibition that allows one to

grasp, at a glance, the artist’s perspective and attitude toward understanding

the world. Out of personal desire, it would have been even better if a few

works from the Fugitive series or earlier pieces

had also been included. Unless an exhibition is focused solely on new works,

such attempts can be helpful in understanding an artist more fully.

Suddenly,

clear white brushstrokes overlap here and there within his field of vision.

They resemble traces that seem to have been mistakenly smeared onto an

otherwise well-made photograph. The paint drips flowing downward subtly force a

sense of accidentality or suddenness. Yet these marks are artificial and

intentional acts of painting—acts of defacement. Works produced in 2010, such

as The House–Blue Roof, The House–Red

Roof, The House–Stairs, and The

House–Ginkgo Tree, all carry the added burden of a sudden brushstroke

on an otherwise intact landscape.

The

scenes reveal neighborhoods perched on steep hillsides, with broken windows and

many houses standing with doors ajar. It is difficult to find a house with an

intact gate or roof. Even when a gate remains, signs of life are hard to

detect. From these details, it becomes clear that the landscapes capture

moments just before demolition due to redevelopment.

Between

the brushstrokes and the landscapes, an unspoken distance—an unsettling gap—is

created. It is as if the brushstrokes occupy the space of reality in the

present moment, while the photographed landscapes belong to another place

altogether, another time and space, set at a remove. An ordinary landscape

suddenly becomes a defaced photograph. It resembles a view seen through a

window dirtied with grime. When one encounters a painted figure inside the

window of an empty house where no people remain, the moment is chilling—an

awkward and deeply embarrassing instant. A gaze that once captured an ordinary

house suddenly assumes an unexpected expression. It is an expression that

cannot be understood, an unreadable sign.

The

House–Lettuce, which captures a pile of lettuce growing abundantly

inside a plastic container placed atop a wall, draws the eye to the stark white

brushstroke clearly visible in the lower right corner. Within a single frame,

entirely different spaces come to coexist. In The House–Laundry,

the traces of brushwork and applied color are clearly visible on the hanging

laundry, with even the dripping paint marks rendered explicitly. In forests,

leaves, or walls, colors that do not belong there add further effect. By

painting and adding color, Kang leaves marks atop preexisting photographs,

reconfiguring intact images through acts of defacement and revealing traces of

post hoc intervention.

These

interventions are awkward because they do not belong, and embarrassing because

they are too seamless. They are interventions made to generate meaning.

Although meaning is often said to be a post-event phenomenon, here it is

forcibly imposed through a coercion of the gaze. While landscapes traditionally

function through their own symbolic roles and grammar, Kang attempts to

compensate for the deficiencies of landscape and photography through the act of

painting over them.

These

white brushstrokes—or colored marks—stand out through juxtaposition with the

original landscape, asserting themselves as actions and acquiring the

temporality of the present. Meanwhile, the spatial present of the landscape

recedes into temporal distance, becoming the past.

This

distance allows the landscape to be perceived as something that “is there,”

while the traces transform it into something that “was there.” That “there” now

signifies a place that no longer exists. “Being there” and “not being there”

are no longer presented as the materiality of the landscape, but as a duality

of recollection and fact. It is a response oscillating between reality, refusal

of reality, and negation of reality. The will to alter given reality emerges

through works such as Trainee, Mickey’s

House, and Landscape of Osoe-ri.

The Mickey’s

House series places a toy house in suitable locations within

demolition zones and photographs it together with the surrounding context. Yet

Mickey’s House cannot remain whole either as a toy or as part of a demolition

site. Its awkwardness arises from the intrusion of an alien element into the

landscape. This is where the peculiar unreality of Kang Hong-Goo’s photography

emerges. Perspectives, temporalities, and situations are misaligned, yet

presented boldly—sometimes even nonchalantly. Through comparison between the

existing landscape and Mickey’s House, a new landscape is revealed. As one

gazes at Mickey’s House, the demolished landscape comes into view; when looking

at the demolished landscape, one becomes aware of Mickey’s gaze. Gazes

circulate and intersect.

Mickey’s

House–Clouds causes roof tiles placed atop a wall to be mistaken

for a building, or evokes warmth and wholeness when placed inside the main room

of a half-demolished house. Set within desolate post-demolition spaces, it

becomes something surreal—a dream that once existed but is now gone. Mickey’s

House–Rebar and Mickey’s House–Door,

positioned among piles of discarded steel frames, preserve memories of place

and home. Through Mickey’s House, what no longer exists is shown to persist;

what has disappeared remains present. It is a gaze directed toward something

absent yet existing, gone yet not erased, remaining as lack. Mickey’s House

draws reality into fantasy and fantasy into the realm of real meaning. Fantasy,

as a mode of presentation, becomes a readable language system. Fantasy is

“fundamentally narrative in structure,”¹ a narrative of lack that compensates

for reality’s deficiencies. It is no different from the structure of reality

itself—a fantasy as painful fact.

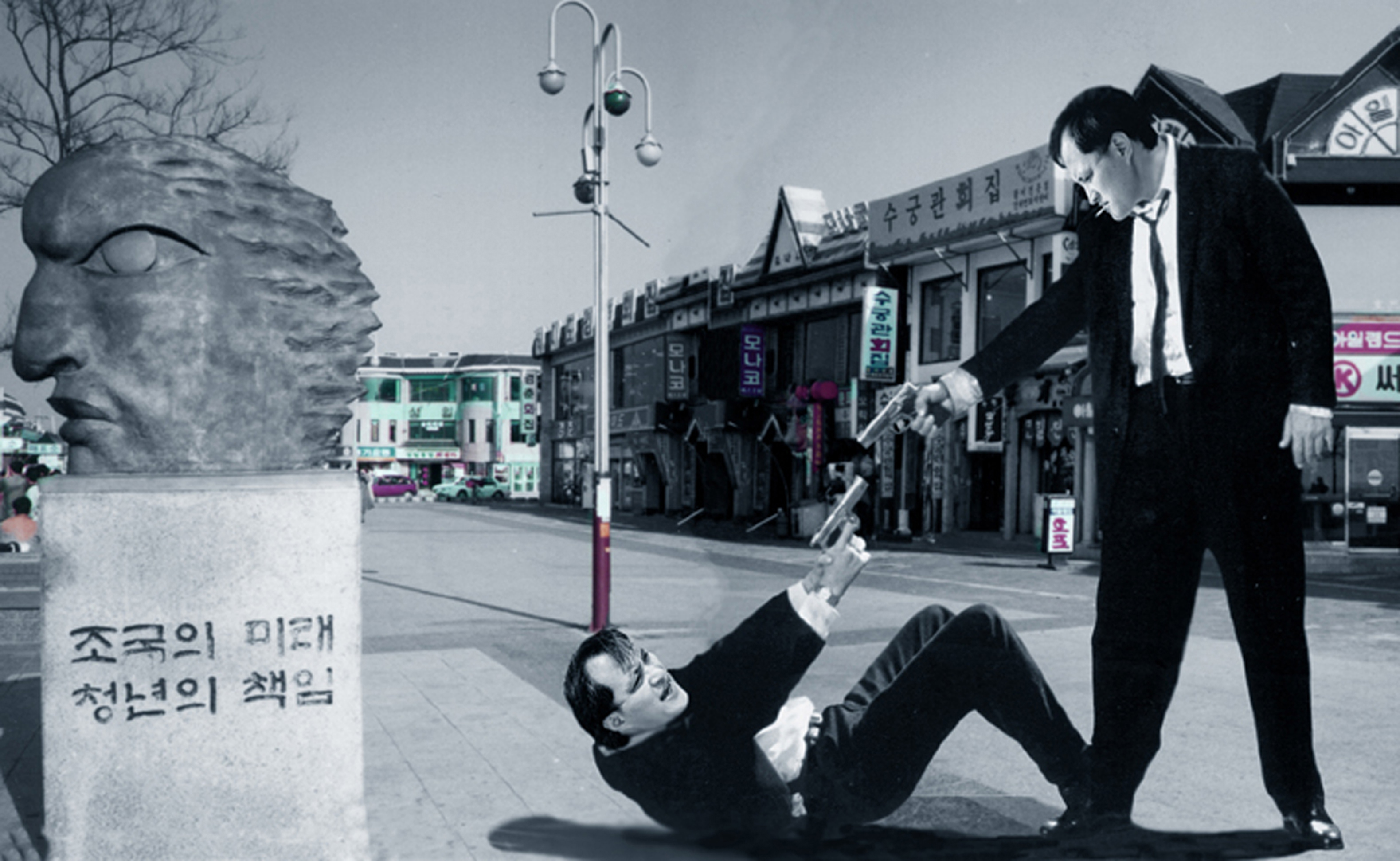

The Trainee series

stars a toy man wearing boxing gloves and no shirt. The appearance of a warrior

from a fighting game elicits bursts of laughter and cynicism, as well as

gestures of pity. It presents a contemporary Don Quixote—feinting emptiness to

conceal weakness. Scenes such as Trainee–Wall-Climbing Skill and Trainee–Training

for an Immortal Body, in which the figure scales walls or leaps over

glass-shard–lined fences, resemble ninjas from Japanese manga. Trainee–Feinting

Emptiness, evoking pole vaulting as the figure grips power lines,

stages a scene straight out of martial arts novels. It is like a pseudo–qi

master boasting before spectators. Yet this bravado does not feel entirely

false, leaving behind a bitter smile.

Scenes

such as Trainee–Circulating Energy and Regulating Breath in

a radish field, Trainee–Red Leaves Flying peering

into a house from atop withered vines, or Trainee–Leaving No

Trace on Snow standing in a snowfield, stand in for the

resistance Kang seeks—resistance that ultimately ends in futility. Actions

occur, yet leave no trace; traces remain, yet something real passes fleetingly

through them. Through this gaze, we encounter something unspeakable that

underlies human stories and guides our lives as reality.

These

works recall Zhuangzi’s parable of the mantis blocking a cart (螳螂拒轍), where the impossibility and unreal premise itself becomes a

source of strength. Through that strength, “fact” endures. Within today’s

photographic landscape, it is not easy to pinpoint where Kang’s maturity,

refinement, or innovation as photography or form resides. In that sense, it is

difficult to judge his works as “good photographs,” yet it is undeniable that

they produce compelling narratives. At the same time, despite his composite

imagery and post-photographic approaches, one cannot deny that his work remains

within the category of traditional photography’s “factual” representation.

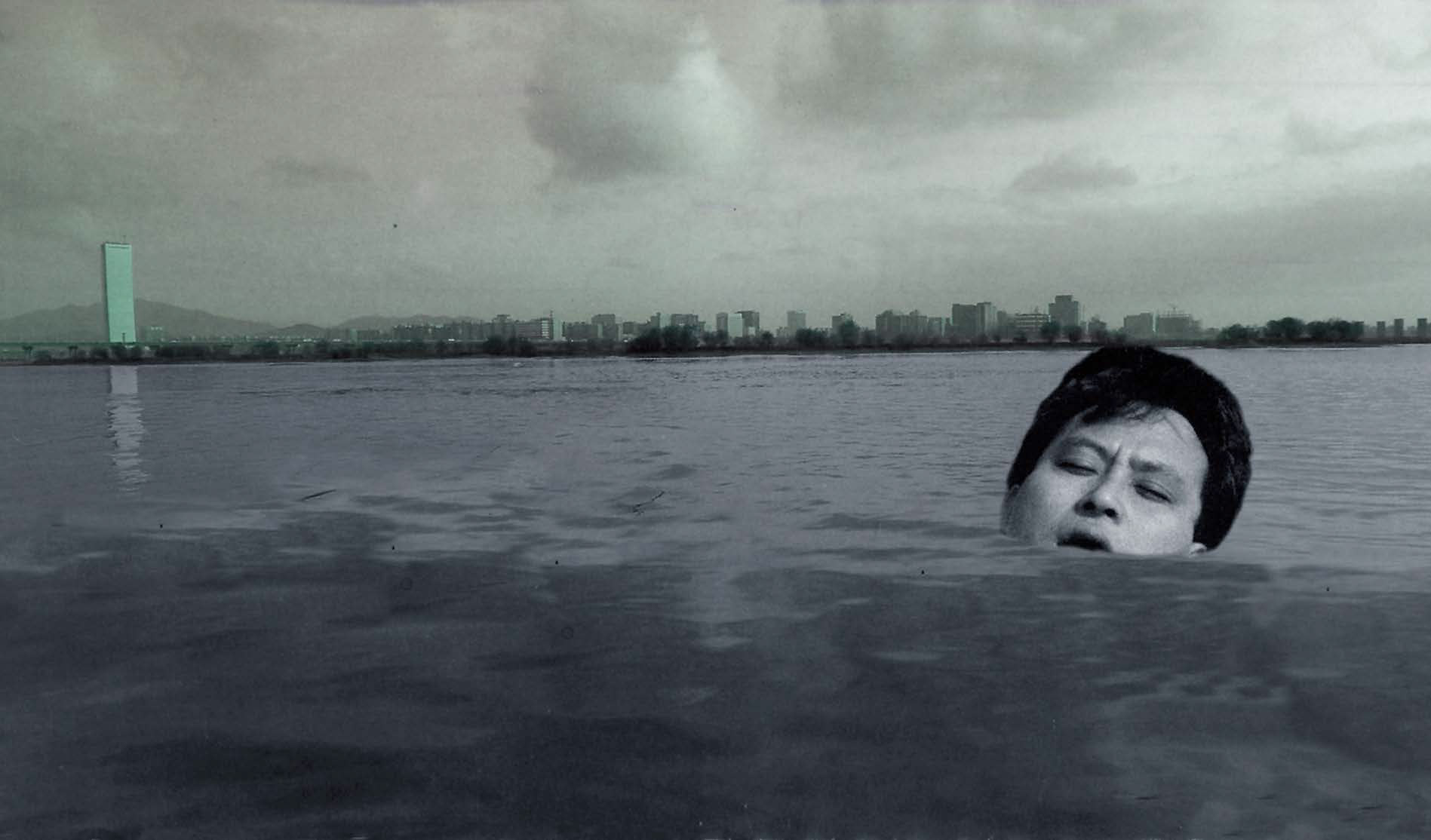

Vanish

Away largely avoids overt artifice. It simply depicts scenes

during or after demolition caused by redevelopment. Between partially

demolished conditions and the desolation of what remains, it reveals an awkward

encounter between memory and site. It shows what will remain as emptiness once

everything has truly disappeared—something absent yet present, erased yet still

there. These works avoid sentimental clinging and maintain a dry, documentary

gaze. Yet scenes such as white apricot blossoms blooming in the center of a

main road, or peach blossoms illuminating alleyways, evoke tenderness and quiet

sorrow.

Compared

to this, Landscape of Osoe-ri operates

differently. It juxtaposes old and new, intact remnants amid collapse, and

speaks through stark contrasts. It compares the arbitrary violence of

low-flying airplanes to power exercised over human presence. Scenes such

as Landscape of Osoe-ri 12, with laundry hanging in

alleys inhabited by those unable to relocate, and Landscape of

Osoe-ri 10, showing a schoolgirl walking between ruined and intact

houses, exemplify this approach. The contrast is even clearer in Landscape

of Osoe-ri 5, where an orange excavator or red-roofed village

disrupts a gray-toned environment.

Kang insists on a clear gaze toward what

remains until the end—not as trace, but as reality to be remembered.

From Fugitive through Landscape

of Osoe-ri to The House, Kang continues

to narrate the absence of what “is there.” What is there flees, is abandoned,

or is interrupted by absurd wholeness, as in Mickey’s House.

The disappearing intervenes in what remains; traces push landscapes aside. What

“is there” suddenly intervenes as something real that was lost. In this way,

Kang unsettles both his own gaze and that of the viewer.

Through trace-based

intervention, the present defaces the given scene; traces become the present,

and landscapes become the past.

Through

this intervention of traces, Kang shifts landscapes into systems of meaning and

liberates photography from monotonous acts of capture or genre consciousness.

Through compositing and deviation, he reconstructs “fact” within photography.

This

awkward and embarrassing intervention demands a different perspective on

photography’s material immediacy and reveals photography as a composite domain.

In Kang’s work, photographed landscapes are recombined like linguistic

signs—nouns, adverbs, and verbs forming new sentences. His photographs are his

sentences. Like other media, they awaken us to the formation of new meanings

through combination. These sentences are not fiction; they reveal “fact.”

“We

know that there exists a world we do not know. Yet that unknown world does not

exist for us as ‘fact.’ Wittgenstein says: ‘The world is not the totality of

things, but the totality of facts.’ If no perception can be free from

experience, prejudice, and social context, then the perception of fact always

accompanies interpretation. In that sense, ‘fact’ is already interpreted

fact.”² Kang’s method is an interpretation of landscape, through which we come

to recognize the social reality we inhabit as “fact.”

However,

when photography becomes merely a medium of compositing, doubts remain as to

whether photography’s own domain may be dismantled or closed off. As seen

in The House, the passivity of composite

photographs—too conscious of traditional photographic grammar—renders the

digital transformation of images cautiously evaluated. Moreover, it is

difficult to articulate the difference between a single original object painted

upon and a photograph taken of that object. As the artist’s gaze shifts from

Osoe-ri to The House, it becomes more indirect, moving from concreteness toward

abstraction, growing gentler—a point worth observing further.

Art

expresses that something unexpressible exists in every expression, and the

critic’s task is to respond to the implications of that unexpressible by

challenging the forms and systems that have obstructed the presence of true

art. The task of thought is to respond reflectively to what is happening in the

present, thereby discovering new rules and modes of action. In this sense, Kang

Hong-Goo’s work presents us with a lucid stance. Yet whether our continued

expectations and doubts regarding composite realism and the existence of the

nonexistent stem from the obstinacy of photography as a medium remains an open

question—one that Kang himself must address, alongside his acts of painting

over photographs.

¹ Edited,

Jacques Lacan, The Adventure of Thought, Mati, 2010, p.193.

² Semiotics, Yonsei University Press, 2005, p.14.