Since

the early 1990s, when the era of digital photography began to blossom, Korean

photography has undergone rapid changes throughout the 2000s in its modes of

production, editing, distribution, creation, and exhibition. At a time when

theoretical approaches and academic discourse on contemporary Korean

photography were still insufficient, Kang Hong-Goo’s photographic experiments

provided crucial points of departure for reflecting on the characteristics of

the photographic medium and the new possibilities of digital photography.

His

attempt to dismantle the formal aesthetics long upheld by the photographic

field—namely the dichotomies of “pure/non-pure” or “straight/made”—and to

expand photography as image, along with his imagination and practice rooted in

subculture (popular culture, or what Kang himself has defined as the position

of a B-grade artist), opened up a new phase of realistic (documentary)

photography that approaches truth.

Even

within a rapidly changing media environment, Kang Hong-Goo demonstrated

vitality in developing new photographic languages and creative compositions,

generating a joyful kairos. As a first-generation digital photographer, he

symbolically and persuasively presents the realities of Korean society through

diverse photographic techniques and transformations. His so-called Kang

Hong-Goo–style allegorical montages—connecting and reconstructing frames

divided through Photoshop, applying or letting paint drip onto photographs,

drawing objects that were not photographed, or producing images whose status as

photography or painting (taken or drawn) cannot be clearly determined—have been

continuously produced, creating reverberations within the photographic field.

Kang

Hong-Goo’s artistic practice can be broadly divided into five periods by year.

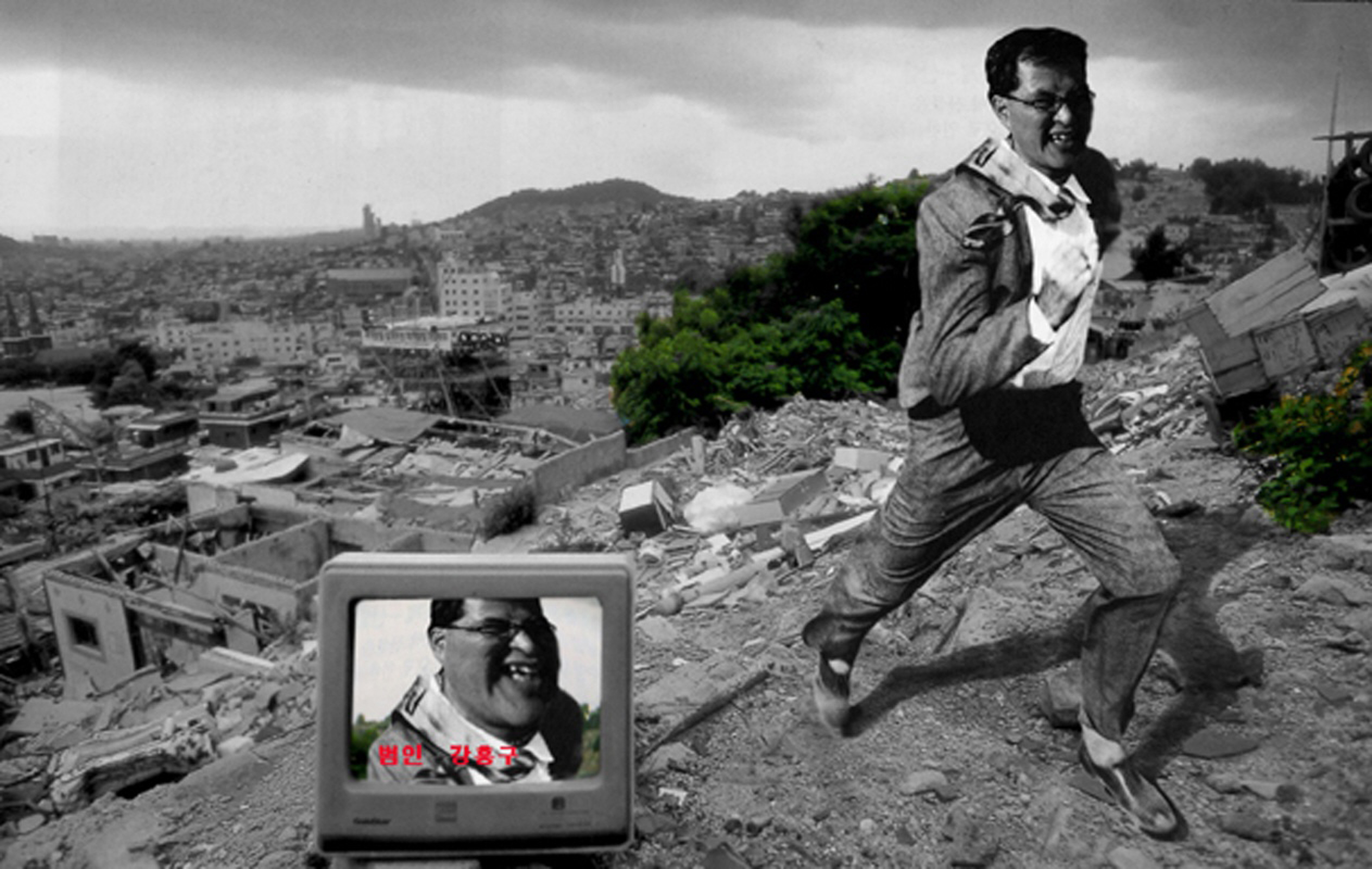

From 1992, when he first purchased a computer, to 1998, before digital cameras

came into widespread use, he conducted a wide range of media experiments.

During this period, he primarily employed photomontage and photocollage

techniques, producing images by scanning and compositing photographs from

magazines or commercial postcards, or by photographing with a film camera,

printing the images, and reconstructing them through a scanner. He also used a

“hand-held scanner” to secure digital data.Major works from this period

include Self-Portrait (1992), Who Am

I (1998), and Fugitive (1996),

which pursue the identity of the artist/individual through constant

self-surveillance and doubt regarding one’s position as both an artistic

creator and an everyday person.

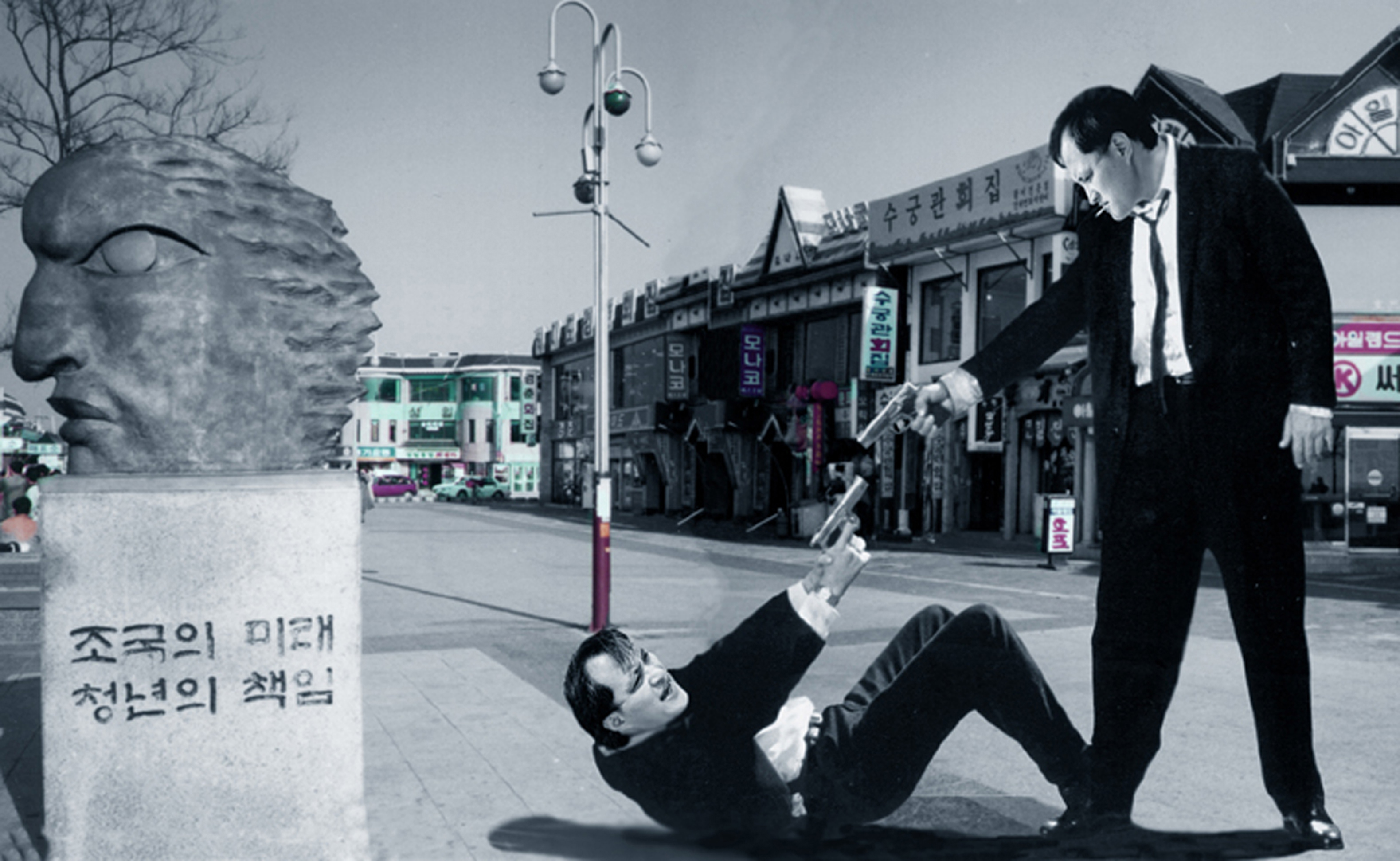

In Happy

Our Home (1997), Kang examines the realities of the family by

portraying unhappiness and exposing contradictions within the family system and

domestic life. The series War Phobia (1998)

vividly reveals the artist’s latent fear—an anxiety naturally internalized

after the Korean War. These early works were brought together in his second

solo exhibition, 《Position · Snob

· Fake》(Kumho Museum of Art, 1999). In this exhibition,

Kang Hong-Goo formally declared himself a “B-grade artist,” drawing public

attention.

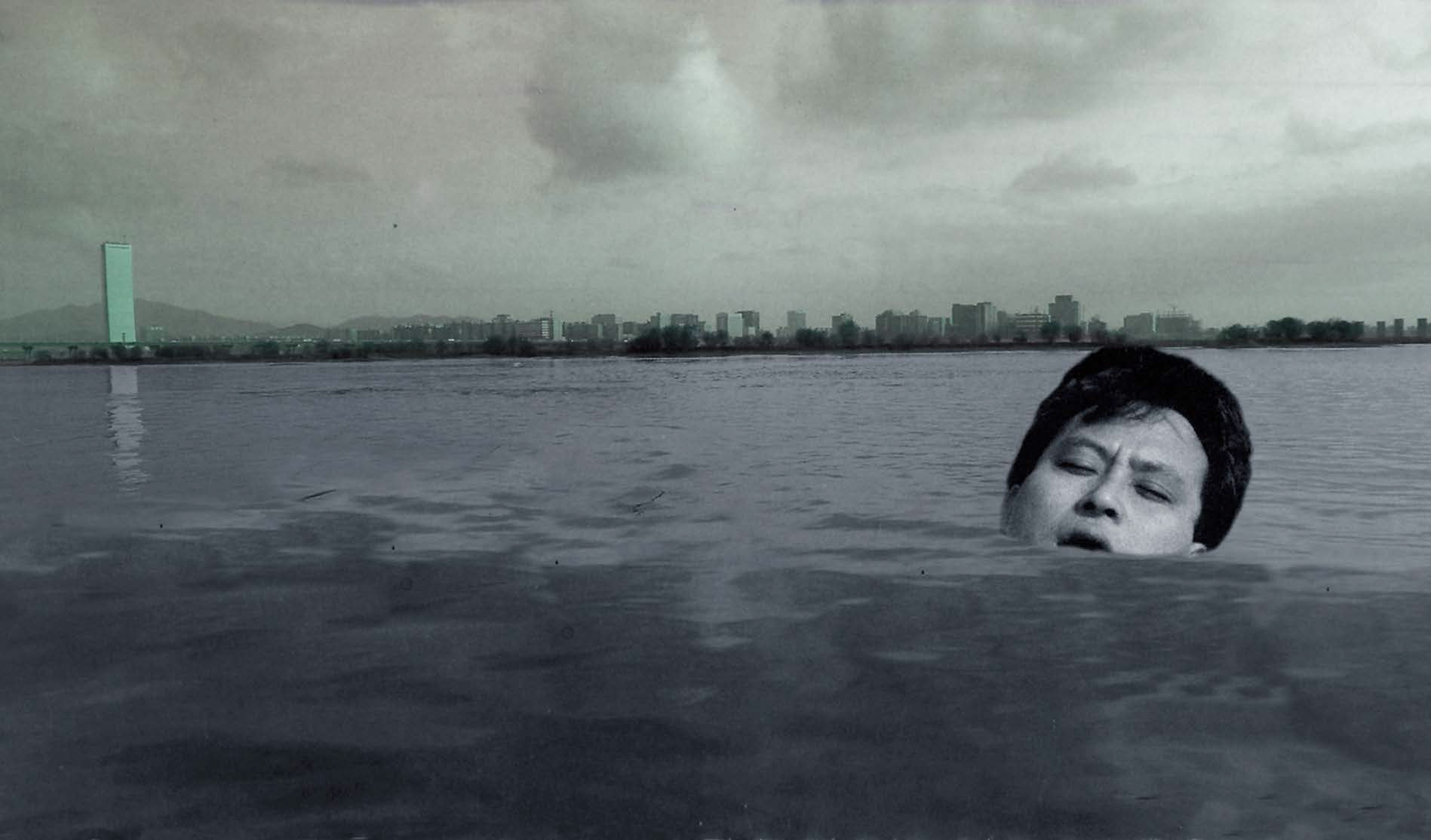

The

second period begins after 1998, when Kang started using digital cameras and

produced his distinctive digital landscape series. Formally, this period is

divided into black-and-white panoramas and color panoramas. The black-and-white

panoramic series includes Greenbelt(1999–2000), Hangang

Public Park(2001), Sea(2002), Busan(2002), Drama

Set(2002), and Fish with Landscape(2002).

These works depict ordinary landscapes encountered during Kang’s walks, yet

they unfold uncanny scenes of subtle dissonance and distortion characteristic

of our time.

The

photographs of the greenbelt—development-restricted zones on the outskirts of

Seoul—are irony itself. As Kang himself has noted, the greenbelt in his

photographs is by no means “green.” Under the fervor of development, traces of

disorder, pollution, decay, and deterioration are hidden within the

black-and-white images.

Hangang Public Park, Sea,

and Busan share a certain affinity in both content

and form, resembling scenes from a Hong Sang-soo–style film that seem to unfold

in real life. Sudden, unexpected, and bizarre elements appear openly and

without disguise. In Fish with Landscape, an

unfamiliar, alien-like other roams freely as if it were in its natural habitat. The sudden appearance of a fish transforms the photograph into a dream, a film,

or a fantasy. This series subsequently leads to object-based photographic works

such as Mickey’s House and Trainee.

Drama

Set reflects on the nature of floating images—images that are

loosely set up, manipulated, and endlessly replicated in order to be seen—by

using actual filming sets. If an image is something that appears real despite

lacking substance, Drama Set is a meticulously

staged work that reveals the ephemerality of images.