The Youngest Exhibition Today

Snow will, “inevitably,” melt and disappear. Precisely for this reason,

the artist declares—in a notice affixed beneath the pedestal—that he will not

exhibit a marble sculpture representing snow. This notice itself becomes the

work. By the nature of mirrors, whatever appears on their surface is fleeting

and singular. Yet the artist constructs a mirror that rotates continuously by

motor, staging a counter-reflexive situation in which not only the reflected

subject but the artwork itself enters a state of perpetual “idling.”

On a

single rotating platform, everything is bound to turn together in a shared

destiny: here, the artist sets two identical chairs in motion, one rotating

clockwise, the other counterclockwise, repeating their opposing movements.

Sunlight leaking through a small hole in the wall into a darkened room shifts

and vanishes moment by moment. The artist, however, meticulously traces each

fleeting imprint of light, circling it to leave an artificial record on the

wall.

Phrases long circulated and revered—such as “修身齊家

(self-cultivation and regulation of the family)” or “無爲自然

(effortless action in accordance with nature)”—carry a certain weight and aura

of authenticity. The artist knows, however, how such maxims have been

fragmented into hollow signifiers of spirit, misused as aesthetic masks to

serve private interests. Accordingly, he disassembles these four-character

idioms or ostentatiously gilds them in gold leaf.

In the works presented at Ahn Kyuchul’s solo

exhibition 《Ahn

Kyuchul Multiplied》 at Amado Art Space, such acts of “countering” or

“resisting” what is ordinarily taken for granted—both in terms of reality

perception and physical order—operate in mutual relation. In logical terms,

this relation corresponds to paradox: as in the etymological structure of

“para-doxa,” meaning “beyond common opinion,” the two coexist, with the latter

intervening in the former.

I would argue that this paradoxical relation—this

resistance or intervention enacted to exceed the self-evident—constitutes the working

method Ahn Kyuchul has sustained for over forty years, having described his own

artistic practice as “a question posed to the paradoxes of the world.” I

further wish to suggest that this paradox functions as a kind of “thorn in the

mind,” enabling this mature artist, now having reached the age of “following

one’s heart” (從心), to remain young through logical tension and

heterogeneous modes of expression even in his most recent solo exhibition. By

this I mean that a critical consciousness of the world persistently unsettles

the artist, denying him complacency and prodding him toward something better.

It is in this sense that my opening reflections,

written through the mediation of his works, seek to demonstrate how such

tension and heterogeneity in 《Ahn Kyuchul Multiplied》 emerge

through interference among humanistic contexts and artistic conditions.

Realist, Idealist

In short, Ahn Kyuchul’s paradoxical practice of art—responding to the

paradoxes of the world with paradox—entails a humanistic dimension in that it

produces critical thought through form. At the same time, it preserves the

genre-specificity of art by visualizing paradoxical logic through sculptural

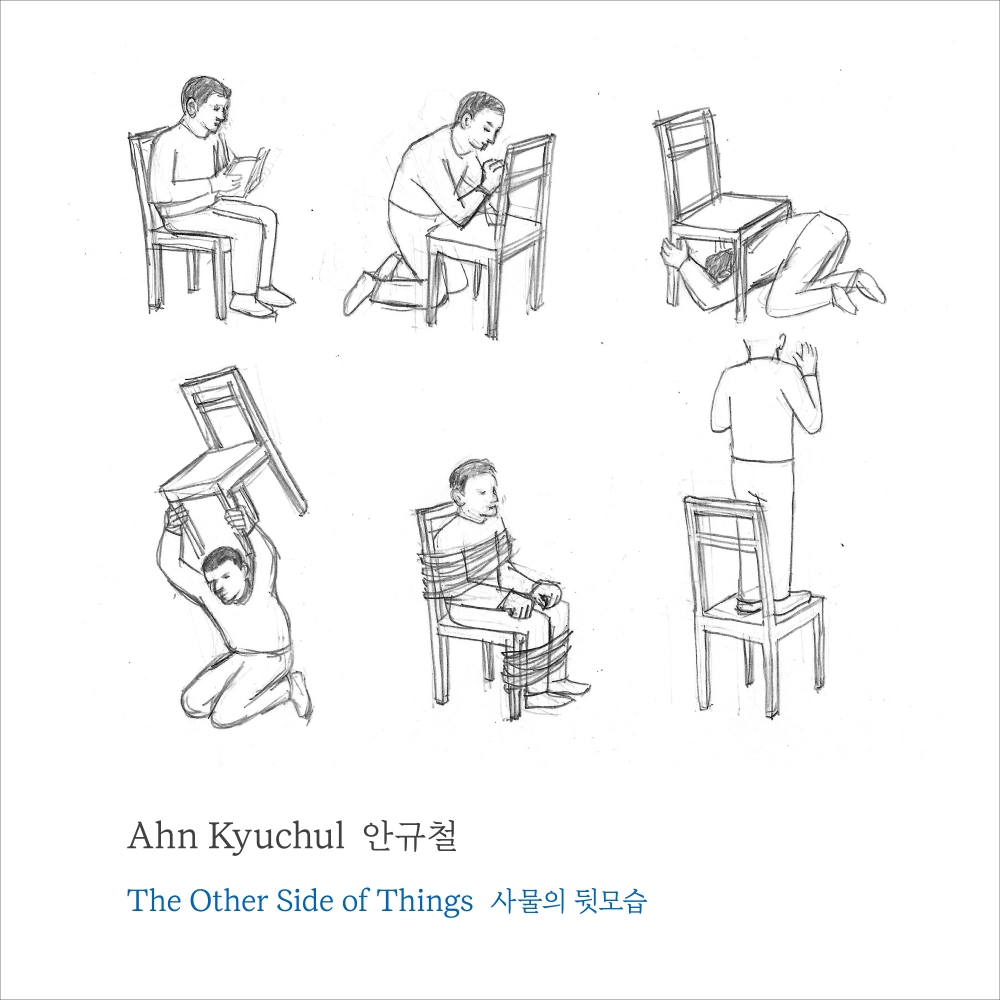

means. He takes the mechanisms of physical reality and given conditions, along

with general modes of perception, and identifies their internal limits or

contradictions, revealing something other than what is already there.

On one

level, this entails creating sculptures, drawings, texts, paintings, videos,

and installations that outwardly embody the tension of paradox between these

two registers. On another level, it involves ensuring that such formally

realized works are read not merely as irony, but as the language of paradox

that—however impossibly—provokes truth.

Ahn Kyuchul, who has devoted himself to writing as much as to visual

art, appears acutely aware of this dimension of his practice. According to him,

objects possess the dual function of intervention and reading, compelling the

artist to work through them:

“Our surrounding objects have at least two distinct functions. One is

their function as tools through which we intervene in the world, and the other

is their function as texts through which we read the world.”

The “world” to which Ahn refers here is somewhat abstract. Elsewhere,

however, he has stated that while his art in the early 1980s belonged to

Minjung Art and sought to “three-dimensionally represent a given situation,”

his studies in Germany from 1987 over seven and a half years shifted his focus

toward “everyday objects and language created by people.” By newly transforming

and assembling such everyday materials, he explains, he went on to create “new

texts” that define his later artistic world.

Taken together, this suggests that Ahn Kyuchul may be regarded as a

realist insofar as he reads the world through given objects. Yet because he

intervenes in the preexisting world constituted by those objects—using the very

same objects—he cannot be dismissed as a passive realist or merely a

“thoughtful observer of the world.” Moreover, given his explicit declaration

that “I oppose art that settles for typical and predictable reactions and

solutions,” he is, at the very least, a resistant realist. Indeed, we might

need to remove him altogether from the category of realism. For although he

distances himself from aesthetic representation and describes his own work as

comparatively “secular,” he nonetheless articulates an ideal state of the

artist and the artwork as follows:

“I dream of a state in which a single work, the trajectory of a single

soul, naturally emits such light—like moonlight that unsettles a person’s heart

and keeps them awake at night.”

This passage recalls Georg Lukács’s opening sentence in The

Theory of the Novel, which speaks of an era when people could gaze at

the starry sky and read from it the map of the path they had to follow. Lukács

posited ancient Greece as a “completed culture” of [the West], meaningful not

only as a lost past but also as a utopian goal. I suspect that Lukács’s

aesthetics may well inhabit Ahn Kyuchul’s thinking on art, insofar as it

encompasses both critique of reality and longing for an ideal society. This

becomes evident when Ahn defines his work as a “question addressed to the

paradoxes of the world,” while simultaneously defining art as “a question about

utopia—about a place that is not ‘here and now.’”

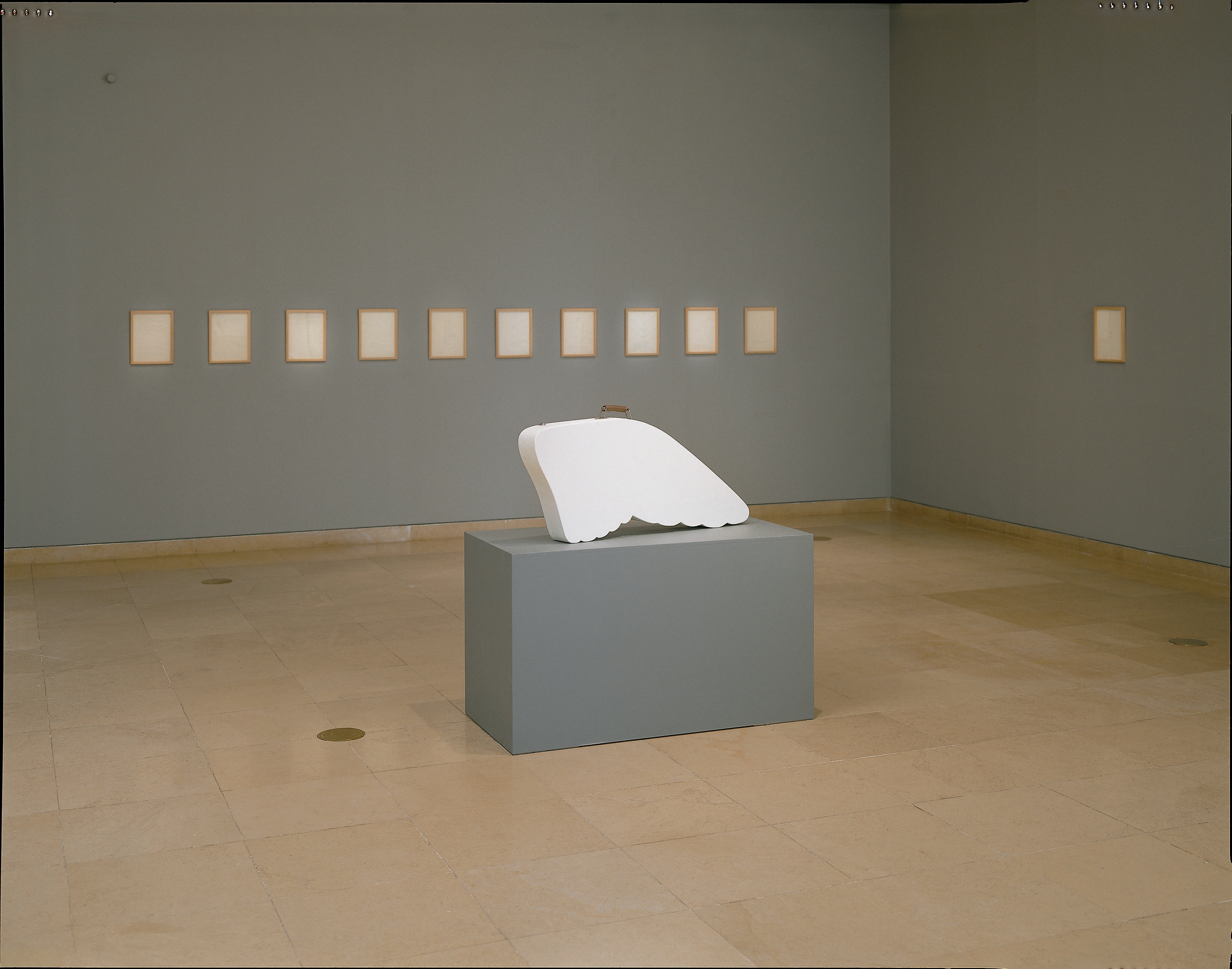

Such complexity is further evident in works like Spiral

Wall (2024), shown in his solo exhibition at Space ISU, where a black

spiral corridor endlessly rotates atop a circular platform, preventing the

walker from ever reaching an end, accompanied by the text “an unattainable

utopia.”

Is Ahn Kyuchul, then, an idealist? Excluding the pejorative sense of

“idealist” or “conceptualist” often applied to him during the mid-1990s, when

he returned from Germany as an unknown young sculptor, I would argue that he is

indeed an idealist—one who begins from reality and works toward a better world.

His artistic practice is oriented toward utopia as an impossible goal, one that

can only be pursued endlessly. In this sense, he repeatedly poses questions

toward utopia in its ambivalent etymology, as coined by Sir Thomas More: both

“no place” (ou-topos) and “good place” (eu-topos).

N Ahn Kyuchuls Cultivating an Aesthetics of Existence

Regarding Rotating Mirror (2024), Ahn Kyuchul wrote

that it mirrors “my former position of believing that the artist should be a

mirror reflecting the world.” Having worked incessantly through “reflection and

self-reproach,” he realized that “the world does not change that way.” Thus,

declaring that “as the world turns, I too turn,” he created a work in which a

small, 55-centimeter-diameter mirror rotates endlessly by motor. At first

glance, this may appear as a cynical form of conceptual art, combining nihilism

and anti-aestheticism—a reading the artist himself may have invited. Yet

precisely because he confesses such intentions and inner thoughts through both

work and writing, it would be reductive to define Ahn Kyuchul as a cold

conceptual artist.

Here, I draw attention to humanities scholar Lee Chan-woong’s analysis

of MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2015: Ahn Kyuchul – The Invisible Country

of Love, in which he distinguishes Ahn’s work not as Joseph

Kosuth–style “dictionary conceptualism,” but as “poetic conceptual art” that

transforms everyday objects into poetic ones. Lee compellingly argues that Ahn

employs irony as an “essential rhetoric,” detaching objects from their

utilitarian function and turning them into signs that collectively form a poetic

world within the exhibition. While I agree that Ahn’s practice transforms the

existing world through questioning, reassembling it into new “texts” or

“unattainable utopias,” I differ on whether his rhetoric is limited to irony or

confined to a “poetic tradition of conceptual art.”

In Ahn Kyuchul’s writings and artworks, rhetoric exceeds the mere

presentation of contradiction and instead induces a form of awakening. In this

sense, paradox—encompassing irony—offers a more fitting framework. Particularly

important is the fact that Ahn has consistently remained wary of conventional

formal beauty, while meticulously articulating, almost obsessively, both his

critique of the world and his self-reflective, self-reproachful confessions as

a critic within it.

For these reasons, I believe that, whether consciously

or intuitively, Ahn Kyuchul’s practice has oriented itself toward an

ontological aesthetics and ethics. It is telling that this orientation emerges

through 《Ahn

Kyuchul Multiplied》, a solo exhibition at Amado Art Space—an alternative

venue modest in scale and institutional authority. The works are dispersed

across twelve rooms and the rooftop, reflecting the spatial conditions of the

venue. One artist divided into twelve. Here, the number “12” signifies not

merely an integer n, but the aesthetic fragmentation of contemporary art and

the artist’s multiple identities.

Accordingly, 12 Ahn

Kyuchuls lacks exhibition-engineered coherence or adherence to a

singular aesthetic value.

Ahn’s first animation, Walking Man (2024), and the

single-channel video Falling Chair – Homage to Pina (2024),

in which the artist performs himself, are projected not onto pristine cinema

screens but onto the rough, aged walls of an alternative space. The rooftop

installation Three Ways to Remember Snow stands exposed

throughout the exhibition to harsh external conditions. Yet these qualities do

not diminish the exhibition.

On the contrary, they lend greater sincerity to

the themes explored across other works—paintings that meta-critique idealist

aesthetics and monochrome abstraction, sculptures that question art

institutions, and installations grounded in poetry that evoke moral action,

ethical awareness, and consolation.

In this way, each room allows viewers to see, hear, and read the forms

and contents Ahn Kyuchul has pursued, without reservation, as “Multiplied Ahn

Kyuchul” addressing the world.

Michel Foucault investigated the totality of practices that constitute

Western society, describing them as a long-standing continuum of “technologies

of being,” an “aesthetics of existence,” and “techniques of the self.”

According to Foucault, people have historically engaged in voluntary and

reflective practices to establish their own rules of conduct, to transform

themselves, and to elevate their lives to an ontological plane imbued with

aesthetic value.

While Foucault’s archaeological method addressed vastly

different scales, I would venture that the most fundamental impulse behind Ahn

Kyuchul’s lifelong artistic practice and writing resonates with the aesthetics

and ethics of existence that Foucault articulated. It is a matrix of practice

through which one continually reflects on oneself, questions the world, and

shapes matter and thought in pursuit of a better place—so that one’s own life

may be worthy of value. The artistic subject formed therein is not free, but it

embodies a performativity that does not cease.