We have to cease to think,

if we refuse to do it in the prison house of language;

for we cannot reach further than the doubt

which asks whether the limit we see is really a limit.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

0. The Artwork as Sign

Put bluntly, art is a reconstruction of reality. By emphasizing certain

aspects of reality while concealing others, art reveals what is otherwise

invisible. Through the persistent tension between what is ‘seen’ and what is

‘unseen’, art invites us to reflect on everyday life. This is possible because

art enables dialogue between the artist and the reader (viewer).

Traditionally, art presupposed the artist as a singular origin. The

artist, believed to generate a single, authoritative meaning, regarded the

artwork as an extension of the self—an embodiment of the artist’s voice alone.

Within the communicative structure of artist–artwork–viewer, the viewer was

reduced to a passive listener, while the artist occupied the position of

authority. In the linear structure of artist → artwork → viewer, the artist’s

creative idea was transmitted to the viewer through the medium of the artwork.

The viewer’s role was limited to perception. To encounter an artwork was, for

the viewer, simply to perceive it; doubts such as “Is this really an artwork?”

were unnecessary.

However, with the advent of the twentieth century, artists began

inviting viewers into the communicative structure of artist–artwork–viewer. The

recognition of Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades as artworks does not occur through

mere perception of the object. What one person recognizes as an artwork may

appear to another as nothing more than an ordinary object. The structure artist

→ artwork ← viewer demonstrates that the artwork proposed by the artist is not

a unidirectional transmission but a product of communication. In other words,

the artist’s declarative statement “This is an artwork” is a deferred

proposition that must be validated by the viewer. Until the active viewer

semiotizes the artwork, this declaration remains incomplete.

As such, the post–twentieth-century viewer is no longer a passive

subject awaiting transmission from the artist, but an active participant. The

viewer seeks to communicate with the artist by semiotizing the artwork. Insofar

as artist and viewer communicate through the artwork, the artwork itself

functions as a sign.

I. Ghosts Drifting between Representation and

Presence

Generally, signs are used to transmit information—to tell or teach

others what one knows. For dialogue to occur, the sender and receiver must

share an understanding of the sign as a medium. Without such shared

recognition, dialogue collapses. Thus, a one-to-one correspondence between what

the sign represents and what actually exists—representation without

distortion—is considered a prerequisite for dialogue. But is distortion-free

representation possible?

Representation presents an absent object through a substitute—another

object or sign. Representation presupposes absence. If the object were not

absent, there would be no need to present it through another form. Hence

representation is inherently unstable. It renders the absent object ‘present to

a certain degree,’ but never fully. This paradox is intrinsic to both sign and

representation. Even when an absent object is given form through a sign, it

remains absent. If the sign were to fully saturate the absence, it would cease

to be representation and become the object itself. Representation finds its

resting place precisely at the point where it endlessly refers back to the

object yet can never reach it.

Thus representation is not full presence but

‘partial presence.’ According to Lacan’s mirror stage, a subject who mistakes

this ‘partial presence’ for complete representation is caught in an illusion

produced by misrecognition (méconnaissance), which inevitably intervenes in ego

formation. Between the represented image and the object lies an unbridgeable

gap or fissure. Because representation offers only partial presence, countless

subjects—like ghosts—hover within this gap, striving toward complete

representation. Though invisible, these ghosts exist, and it is through their

languages that we live in society, sustain life, and conduct dialogue—while

forgetting that ‘presence is always only partial’.

II. Semiotic Representation and the Fictional World

Ahn Kyuchul appears to focus on trivial aspects of everyday life,

seemingly representing ordinary objects. Yet according to Ahn, our gaze upon

the everyday is already constrained by a rectangular frame—a “rectangular eye.”

As Adso states in The Name of the Rose, “I have never

doubted the truth of signs; signs are all humans have to find their way in this

world.” We live without questioning the truth of signs, even if what we

perceive as ordinary objects is already filtered through this “rectangular eye.”

Jean Baudrillard argues that “we inhabit a world in which the essential

function of signs is simultaneously to make reality disappear and to conceal

that disappearance. Behind every image, something has vanished.” Signs are not

truth; they are merely signs. They are not pathways to truth but perhaps

instruments that distort or even destroy it. What, then, is visible, and what

has been filtered out?

Society emphasizes a rectangular frame for its members while eliminating

the world that lies outside it. We come to see the world through such distorted

vision. Signs are formed through agreements among members of society. By their

very nature, signs bind the anonymous sender, ‘I,’ and the anonymous receiver,

‘you,’ into the collective framework of ‘we.’

For a subject to exist, it must present

itself through a sign. Yet a sign is not the subject’s true substance but

merely an artificial construct defined by society. Even so, no matter how

artificial a sign may be, the subject cannot exist without identifying itself

with that sign. In other words, the subject mistakes a sign that is not itself

for the self. This suggests that a subject within society must accept the

socially conventional definitions embedded in signs—even if they are

artificial—in order to be granted an identity.

Consequently, ‘he,’ who fails to be

bound within the framework of ‘we,’ becomes a third person who cannot be

incorporated into the ‘we’ established by the social conventions agreed upon by

‘I–you.’ The everyday signs we use so casually already contain mechanisms that

divide and classify the world within themselves. Should we then refuse the use

of signs altogether? If so, we cannot move beyond the point of asking whether

the limits visible to us are truly limits (Nietzsche).

What becomes crucial here is ‘signification.’ This reveals that signs do

not operate solely within binary oppositions. A sign is a space in which the

unconscious and the conscious act together, and within that space are countless

tensions of force lines. Ahn Kyuchul directs his attention precisely to this

point. In this sense, what he seeks to represent through ‘art’ may be the

halting language of innumerable subjects existing in plurality.

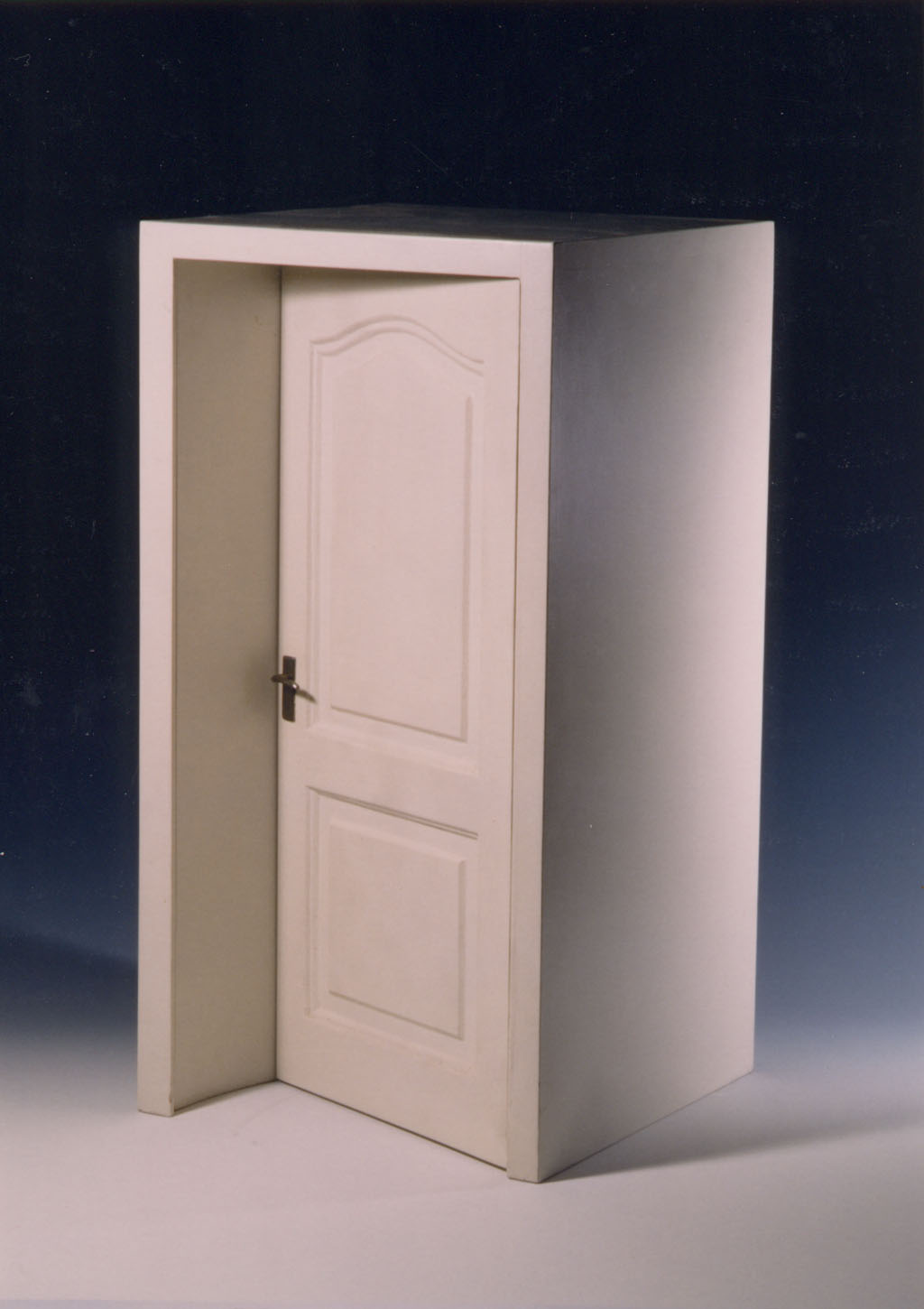

Thus, even when Ahn Kyuchul’s works

appear to reproduce everyday objects, they do not merely replicate things as

seen through a “rectangular vision.” His representation stages the constant

tension between the visible world inside the frame and the invisible world

outside it, and stands as the product of his effort to communicate with the

viewer through this tension—however halting that communication may be.Why,

then, does this language stutter?

Because the relationship between sign

and object cannot be reduced to a single unity, ghosts sometimes repel one

another and sometimes acknowledge one another as they utter their own

languages. When language is released into society through the tension among

these ghosts, it emerges as a hesitant, stammering language of plurality.

Unable to meet or fully approach one another, Ahn Kyuchul’s language of form

floats and falters between subjects.

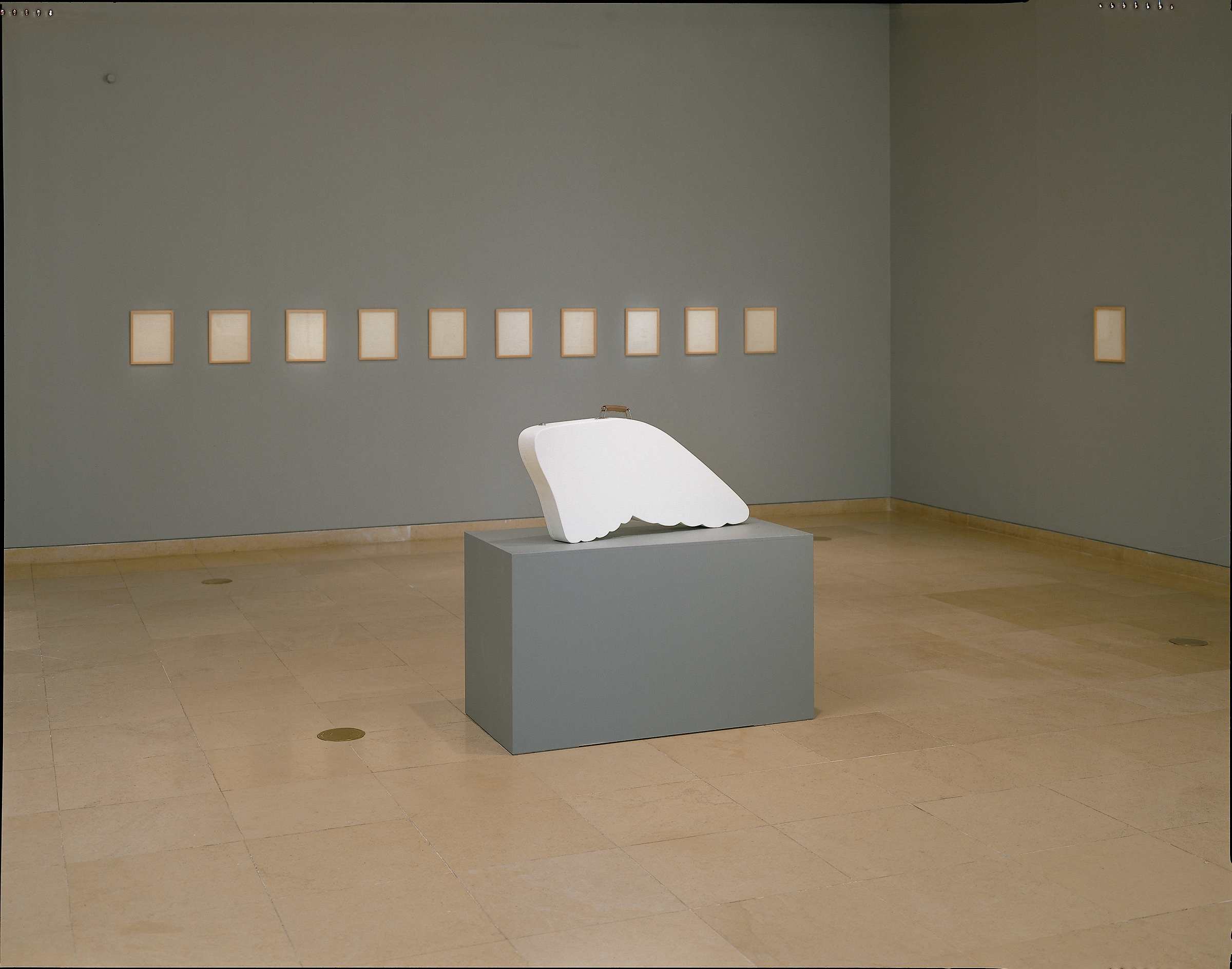

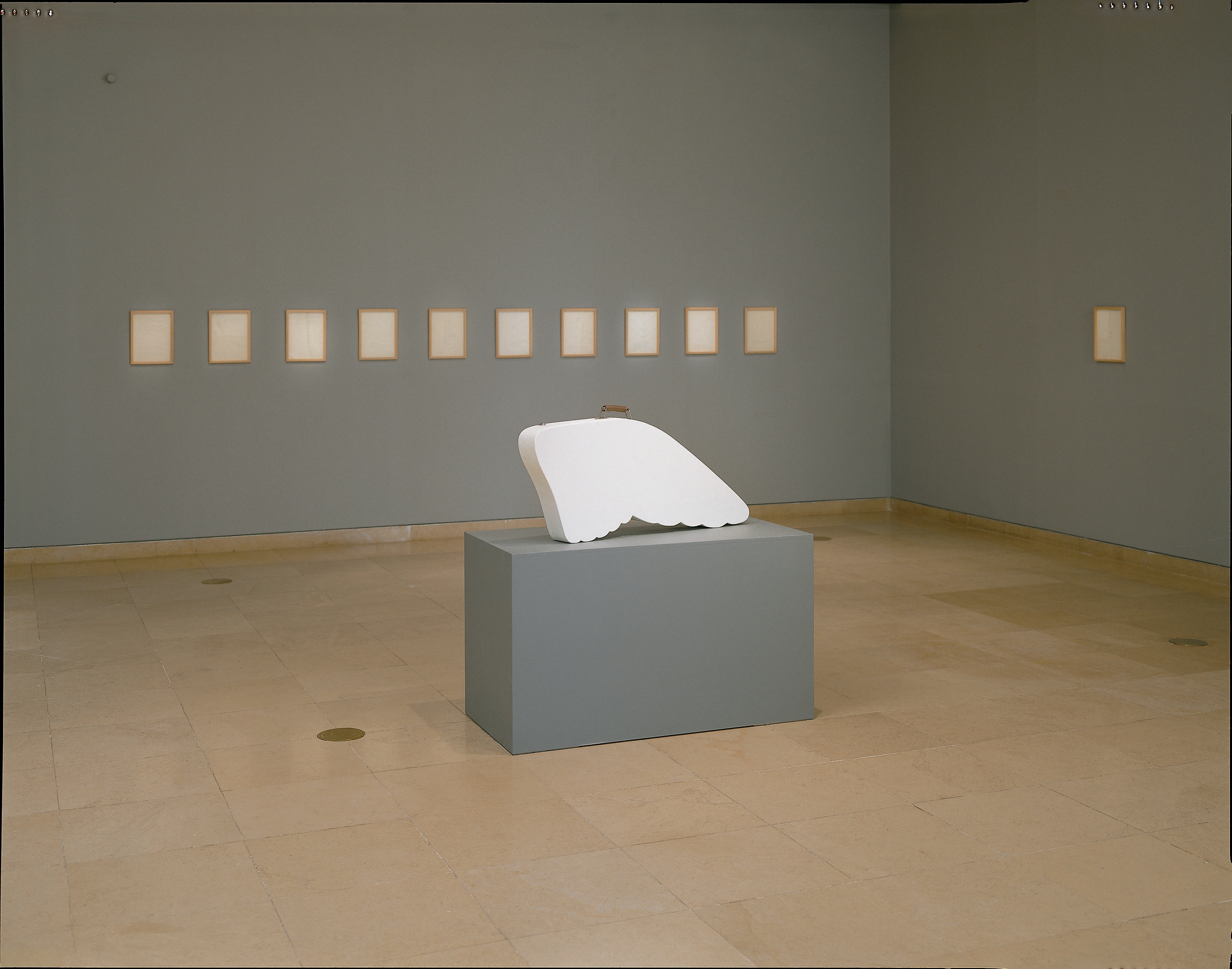

Ghosts that exist yet are forgotten in

everyday life—and the halting languages they generate intersect within a field.

Ahn Kyuchul attends to these stammering languages of those who have become

ghosts through processes of signification. Within changing space and time, he

seeks to represent the tensions among ghosts that momentarily converge yet are

fated never to meet because of irreducible gaps.

At this point, Lacan speaks of

the birth of the Other through the subject’s misrecognition—that is, of the

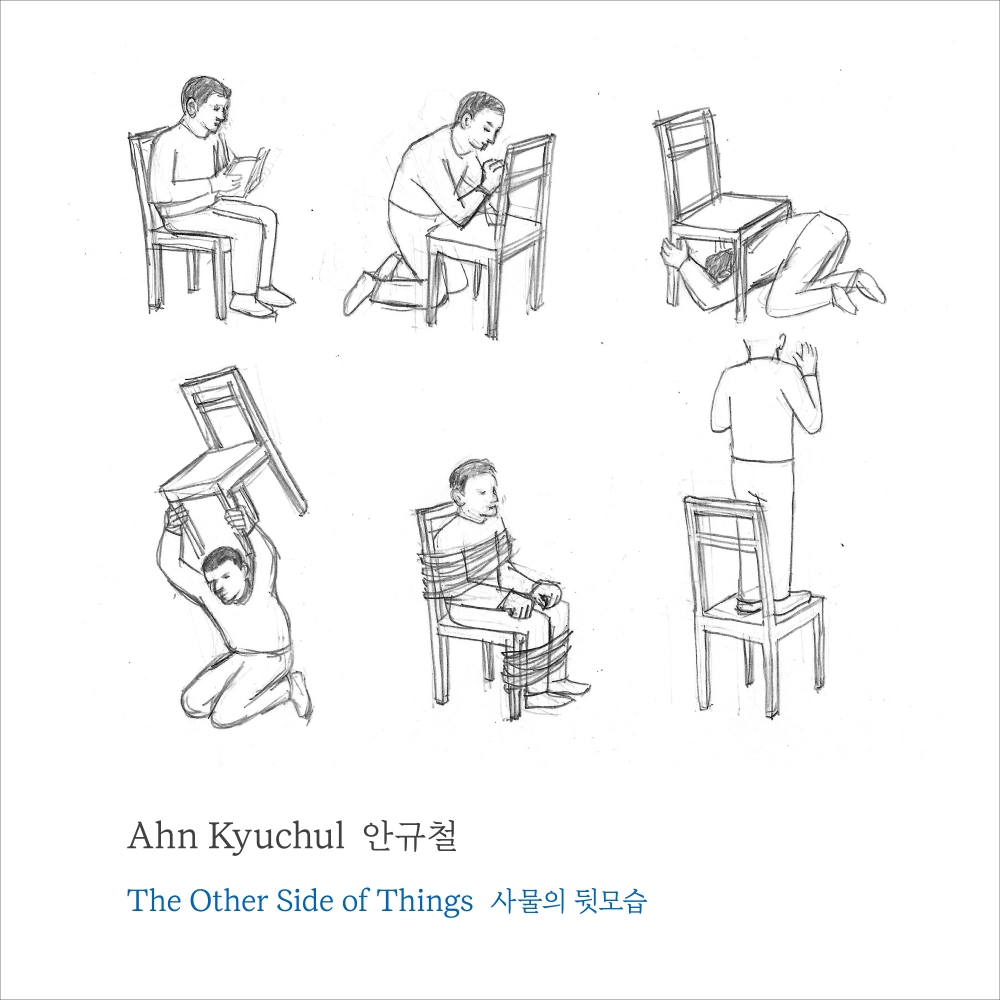

subject’s alienation. Ahn Kyuchul, however, pluralizes the subject and searches

for dialogue among these pluralities. Though their language stutters, these

pluralized subjects continuously attempt communication. Even if the language

that gives form to Ahn Kyuchul’s works is a halting one, his effort to approach

truth through that language never disappears.

III. Cognitive Mapping through Dialogue

Dialogue fundamentally takes place between ‘I’ and ‘you.’ If ‘I’ fails

to recognize ‘you,’ dialogue is severed. Even within the same sign system, when

the other is not recognized, communication remains at the level of command or

transmission rather than dialogue. ‘I’ and ‘you’ recognize one another,

alternately becoming sender and receiver. They are not assigned fixed positions

in which ‘I’ is always the sender and ‘you’ the receiver, but are instead

placed within provisional and mutable layers. The very possibility of dialogue

implies that both ‘I’ and ‘you’ accept the conventional norms of the society to

which they belong.

In doing so, they exist within a shared framework of ‘we.’

Yet through ‘you,’ ‘I’ comes to reflect upon itself, and through ‘I,’ ‘you’

does the same—together reconsidering ‘we.’ This self-reflection mediated by the

other marks the first step toward recognizing that the social conventions

governing a given society are not absolute, but artificial. Although one seeks

to escape, there persists a force that continually confines ‘I’ and ‘you’

within the framework of ‘we’ through artificial regulations. The only way to

move beyond this force lies in an ongoing dialogue through which ‘I’ and ‘you’

advance toward truthfulness. In this respect, dialogue is essential.

Yet in contemporary society, escaping the ‘framework of we’ has become

increasingly difficult. The proliferation of signs within an ever more complex

social structure thoroughly conceals their artificiality. Contemporary society

closes off its own fiction—its constructed nature—by presenting it as reality

through signs. Under such conditions, can art remain free? Might art itself be

disseminating the fictions hidden within reality? Precisely for this reason,

however, the significance of artistic representation as dialogue becomes all

the more critical.

To confront this dilemma, Ahn Kyuchul adopts a distinct strategy:

incessantly doubting art itself. This doubt serves to expose art as fiction.

Although art seeks to represent reality, Ahn Kyuchul reveals through his works

that it ultimately remains fictional—and moreover, that it is a fiction

imagined by the artist himself. What comes to mind here is Fredric Jameson’s

concept of ‘cognitive mapping.’ ‘Cognitive mapping’ refers to the capacity to

infer and navigate the context of a larger, abstract space, extending beyond

the emotional maps formed through immediate cognitive situations—in other

words, an effort to represent that which cannot be directly represented.

This

belongs not so much to mimesis of reality as to an aesthetic practice grounded

in interpretation. It is precisely through art as dialogue that Ahn Kyuchul

renews the classical artistic endeavor of ‘representation.’ He rejects the act

of simply materializing his own thoughts as artworks. Instead, he gives form to

ghosts that betray themselves repeatedly within spaces of signification as they

search for their own identities. This approach further situates both the artist

and the viewer within diverse contexts, inviting them to recognize their

respective limits and, only then, to imagine the possibility of genuine

dialogue through art. Might this be possible because, as dialogue between

artist and viewer unfolds through art, an act of ‘cognitive mapping’ comes into

being?

IV. The Conditions of Dialogue: The Disappearance of

Representation