When I imitate objects and make them under the name of ‘artworks,’ there

is always someone standing at the end of those paths. The paths branch outward

from me. A chair, a room, a house, a forest come into being. And sometimes,

someone traces those winding paths and comes toward me. Without knowing the map

of those paths, without knowing my address, someone will come looking for

me—even if I no longer live there. (Ahn Kyuchul, 1995)

I spent no less than six hours interviewing the artist for this text,

devoting that time entirely to serious(?) discussion about his work. Yet the

more we spoke, the stronger my sense grew that I did not truly know him. It

felt less like failing to reach something that clearly existed than like

pursuing something that was never there to begin with—or something that

continually slipped away. Had I really encountered the “artist” through his

works and words? Or does such an entity as ‘the artist’ even exist? And if it

does, did I meet it directly? If so, is my voice faithfully conveying that

encounter? If not, then is writing an essay titled ‘Special Artist’ anything

more than a futile exercise?

Perhaps the artist does not exist. Or perhaps, even if he does, he

remains forever unknowable. Ahn Kyuchul in particular provokes such doubts,

likely because he himself relentlessly pursues them. By making objects in order

to erase himself—or rather, by erasing himself through the making of

objects—Ahn Kyuchul seems to enact Roland Barthes’ ‘death of the author’ or

Michel Foucault’s view of literature as a form of suicide. Paradoxically,

however, this ‘suicide’ enables me to write about him—freely, and therefore

joyfully. Following Barthes’ invitation, I become a ‘reader’ born in the space

vacated by the author, able to read ‘with pleasure the’ texts he has inscribed.

If the artist exists at all, it is within such acts of reading. His

place of residence is not so much the work itself as the gaze of those who view

it. If Ahn Kyuchul’s works encourage this kind of ‘reading’, it is because he

actively accepts his own dwelling within such gazes. He performs a hybrid

persona—an artist as reader, a reader as artist. Accordingly, what follows is

not an attempt to track down the artist’s “true” identity, but to trace the

personas he reveals.

Looking at Art

If there is a consistent theme in Ahn Kyuchul’s work, it is, above all,

‘art’ itself. What he has been looking at is neither the objective visual

world, nor political reality, nor a transcendent realm—though it may encompass

all of these—but rather the proposition of ‘art.’ As is well known, in the mid-1980s

he was briefly affiliated with Reality and Utterance, turning his attention to

social realities. The Green Table (1984) is a

narrative sculpture that addresses such realities using what might be called

“people’s” vocabulary—plain yet strikingly direct. The theatrical, stage-like

structure of this narrative sculpture continues into his later works.

While the immediate subject here may be economic exploitation, his

ultimate concern lay with art itself within that reality. His use of ‘humble’

materials such as paper clay and plaster, along with a deliberate amateurism in

handling them, amounted to a pointed critique of the grand scales and expensive

materials through which modernist sculpture of the time cloaked itself in

hollow seriousness, as well as of the boom in environmental sculpture producing

monuments for an era of art commodification. Even when he spoke with a

socialist’s rhetoric, he never forgot that he was an artist.

His decision in 1987, at the age of thirty-three, to abandon journalism

and return to Europe to study art was likely driven by this fundamental concern

with art. After passing

through France, he settled in Germany in 1988 and began art school again from

the first year. From this point, his gaze shifted from looking at art

from the outside to looking at it from within. The unpublished drawings

Crocodile Stories (1989), still stored away in his studio

drawers, are diary-like works from this period. By likening himself—adapting to

a new civilization—to a crocodile, he began comparing Germany, where cynicism

toward the 1968 generation prevailed, with Korea, where belief in art as a form

of struggle still lingered.

This narrowing of focus toward the individual and toward art itself

likely resulted from gaining enough distance to perceive the limits of art as a

revolutionary tool or as topical illustration. Toward the

Individual (1989), his first work shown in Germany, bears witness to

this shift: a heavy, somber landscape installed in a darkened space. Phrases

such as ‘Art knows no morality’ and ‘Art is capital,’ emerging from smoke

rising from a chimney, question the meaning of art within society. A snake on the

floor, carrying the phrase ‘toward the individual,’ paradoxically moves toward

a wheeled cart bearing a flag—an emblem of collective history. It seems he

sought to speak about the relationship between the individual and society, and

the place of art within that dynamic.

As his stance shifted toward viewing art from within, his once dark and

weighty tone gradually gave way to something lighter and more witty. This was

not so much a lightening of subject matter as an ability to convey heavy themes

through light narratives—a distinctive mode of expression that became his

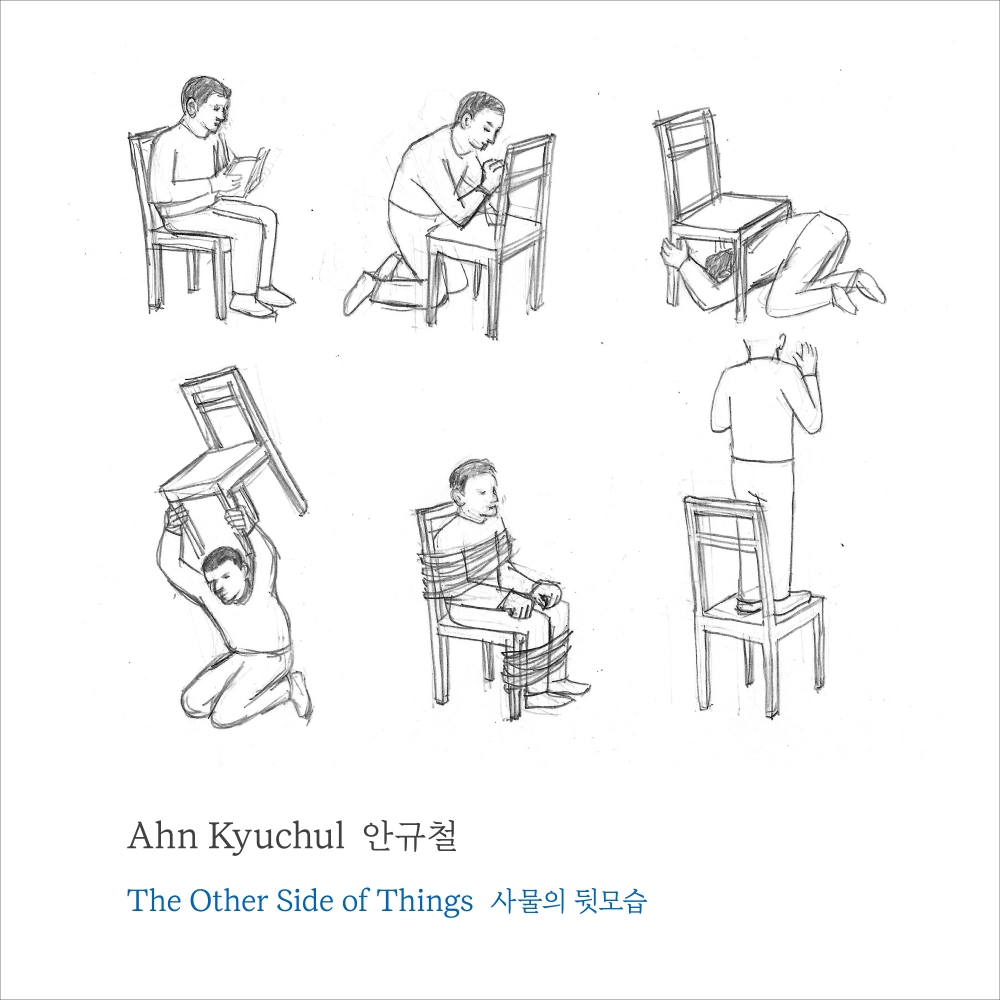

trademark from the early 1990s onward. In Five Questions for an

Unknown Artist (1991), for instance, he embeds ‘serious’ questions

within humorously transformed everyday objects. As he himself has said, this

work signaled his departure from the shadow of political reality that had

followed him, redirecting his gaze toward art and himself as an artist.

Regarding this work—composed of a door labeled ‘Art’ with five handles,

a door labeled ‘Life’ with none, and a chair growing from a flowerpot—Ahn

Kyuchul remarked:

“I have left the lives of ordinary people and must enter the door of

art, but to open that door requires five hands. Inside, I find myself engaged

in the futile act of watering a dead tree.” (Conversation with the author,

1999) Had he continued, he might have said: ‘What is art? Or what can it be?’

Surveying his work as a whole, one finds precisely this process of questioning

and responding. What he practices is not art per se, but art about

art—meta-art.

Yet unlike modernist assertions that define art by isolating its essence

from the outside, Ahn Kyuchul’s reflections on art are inseparable from the

contexts to which it belongs, namely life itself, and are therefore infinitely

open. From this perspective, his early, socially explicit works and his later

works are not fundamentally different; only the tone and emphasis have shifted.

If he can be called a modernist, it is because he never abandons the

proposition of art. If he

can be called a postmodernist, it is because he regards not “art” itself but

“art” as a text. In place of Ad Reinhardt’s “art-as-art-as-art,” Ahn

Kyuchul proposes “art-called-art-called-art.”

The Theater of Objects

It is well known that Ahn Kyuchul writes as much as he makes—and does so

remarkably well. His linguistic sensibility seems to operate even through his

fingertips, endowing the objects he creates with the capacity to ‘speak.’ With

these objects, he stages what Craig Owens identified as the postmodern

‘eruption of language into art,’ or the ‘dispersion of literature into the

aesthetic field’ (Owens, 1979). For him, art is not a visual fact so much as a

sign system akin to language. By reviving language buried by modernism, he

explores the ‘theatricality’ so vehemently warned against by Michael Fried

(Fried, 1967).

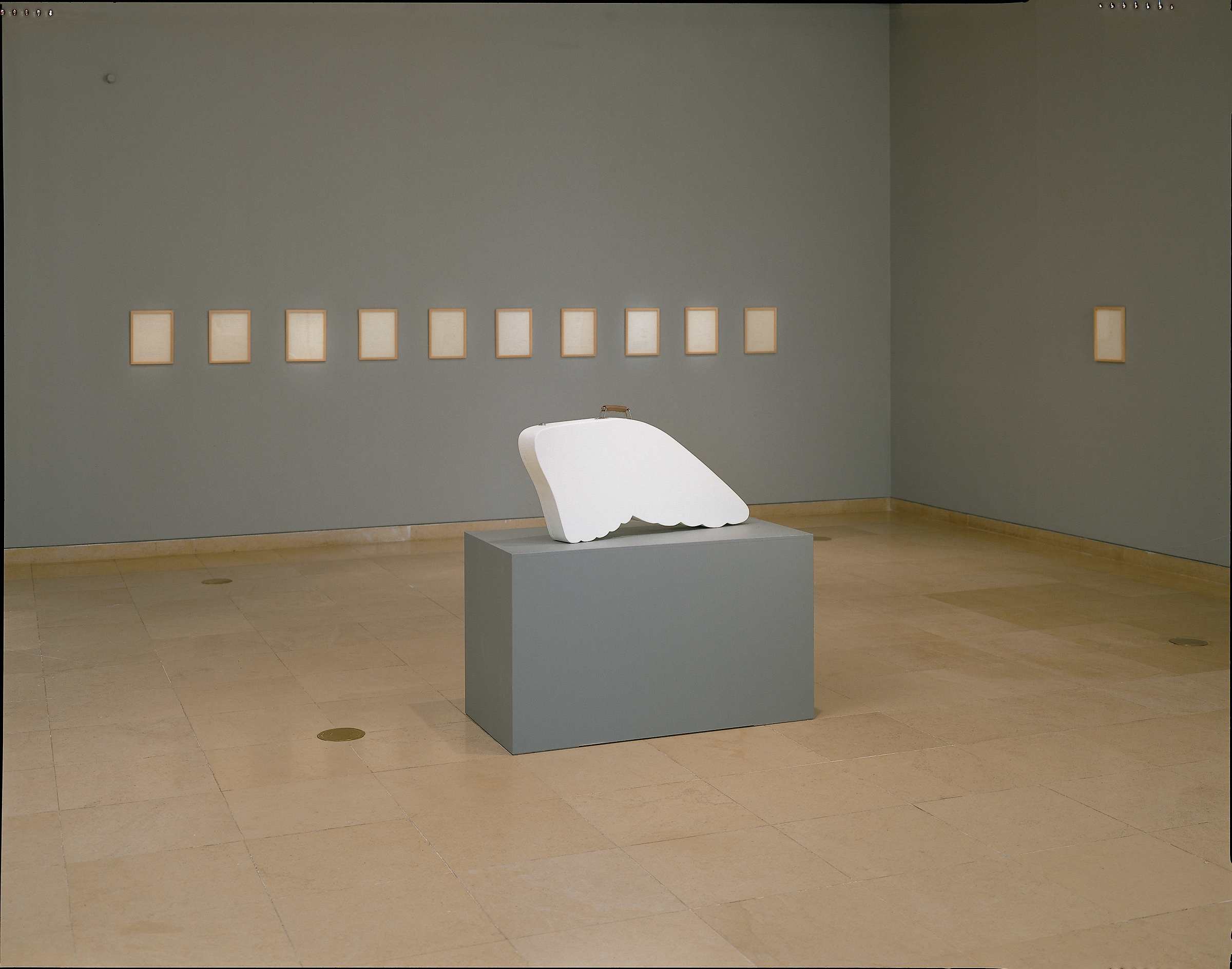

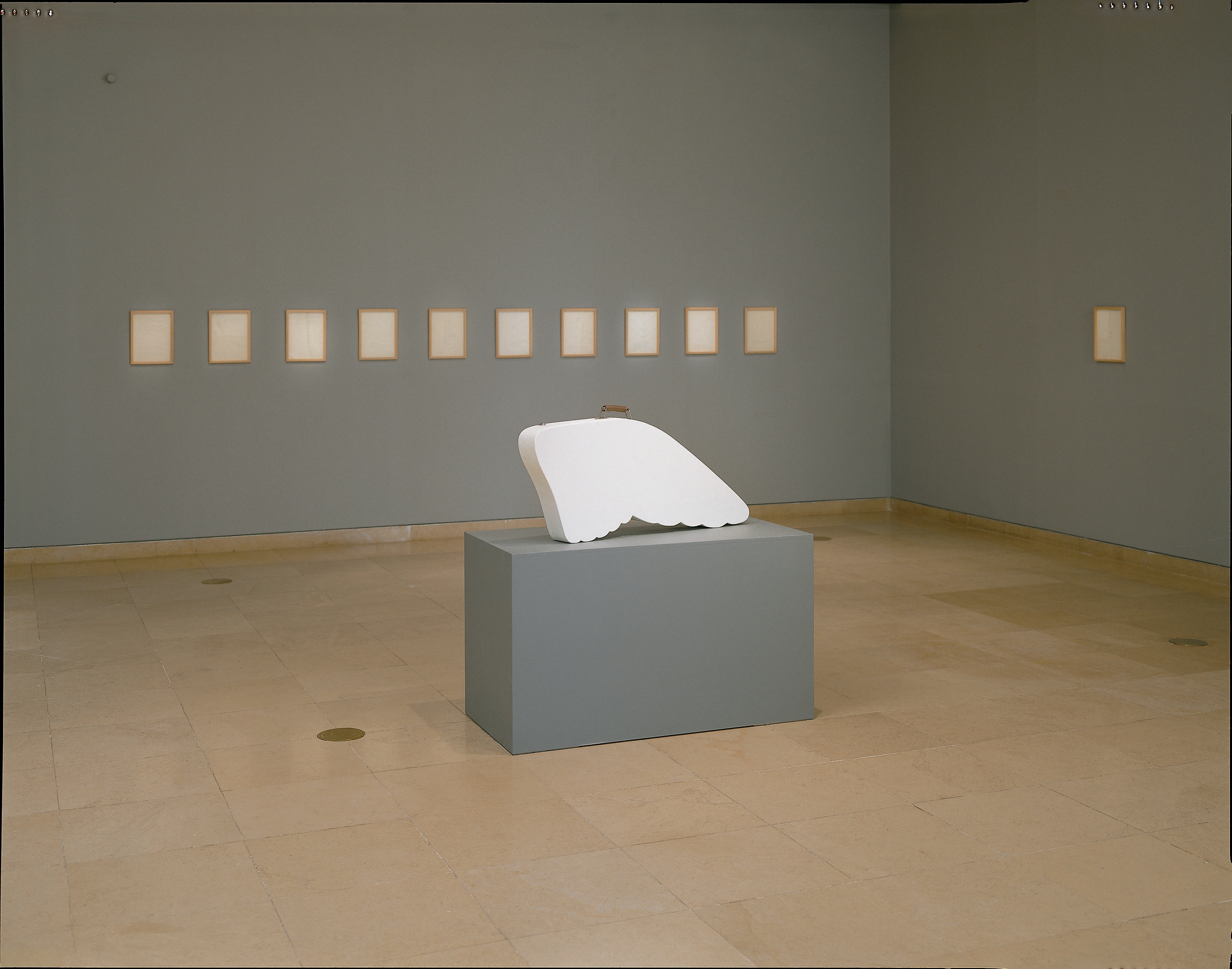

Stage-like sculpture has been present since his early works, but in

recent years everyday objects have become protagonists delivering lines—what

Shim Kwang-hyun has termed a ‘sculptural theater’ (Shim, 1996). In works such

as The Eternal Bride (1994), The Sleeping

House (1996), and A Guilty Brush (1992), objects

are anthropomorphized, each performing its role. Ahn Kyuchul thus becomes both

playwright and director, writing and staging their narratives.

In his works, images, objects, and written language function as equal

components of a larger textual whole. Titles in particular have served to

introduce thematic propositions, and over time written language has

increasingly entered the works themselves, merging with images and objects.