SCULPTURE

AS “IT”

It’s challenging to talk about Chung Seoyoung’s

artistic universe, but it’s not impossible. Her world

does not disappear into some labyrinth. On the contrary, it is lucid and

precise. It is like a form of cross-studies that makes us confront two or more

schismatic realities. If there were a discipline that studied intersecting

times and spaces, might Chung be able to design its methodologies? The things

that she says about her work – flowing and fixity,

receding and approaching, “time that flows without gathering

in any one place” – are neither narratives nor direct

explanations of it.1 She is speaking of the work’s “performance,” as

it leaves the artist’s brain and hands and is left to

operate somewhere on its own, interacting with and reacting against the outside

world. Even after Chung’s artwork has achieved physical

completion, it continues to change as a result of the surrounding atmosphere,

the viewer, and the movements of the world itself.

Within

such a hypothesis (or evidence), we must put before ourselves a more concrete

notion of the “exhibition” – an “exhibition” as

part of a comprehensive world permitted by the artist. The exhibitions that

Chung Seoyoung creates are regions that are meticulously adjusted and

constrained. This is what makes her work appear to the outside. Within a series

of transformations, the artist’s work is left to stand

before the viewer. Chung’s method of freely “sculpting” her solo exhibition is a

technique that guides us to examine some of the issues that she presents. “Sculpting” her exhibition – what is that supposed to mean? This requires that we follow along

Chung’s method of conceptualizing sculpture itself.

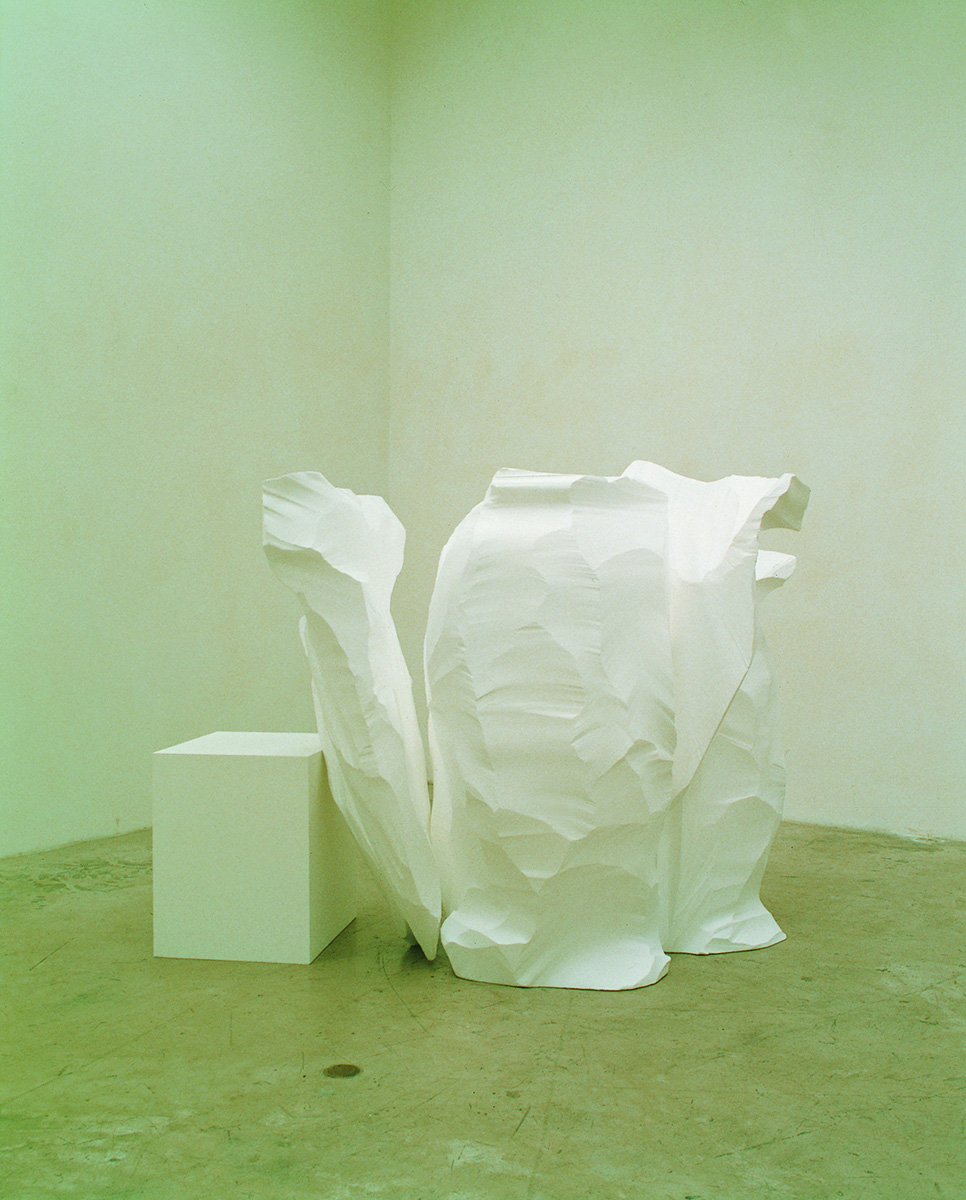

“This sculpture is a remaining part of an installation

work Ghost, Wave, Fire (1998). The intent is to create a sculpture,

which is endlessly moving without a predetermined form or size.”2 “Generally speaking, I am a sculptor. And that is truly too big and

loose of a question, as you said. Even so, I feel I can insert into the

looseness this statement: to proceed from objects to sculpture, you have to

break the “consensus” regarding

things.”3

Chung’s exhibitions are likewise about “fixing in

place things that move without stopping and do not even have a shape.” With her 2016 exhibition Chung Seoyoung (Audio Visual

Pavilion), where she found a new setting for a portion of her forgotten

sculpture that was given the title from Ghost, Wave, Fire (1998), the

matter that was being problematized by means of the artist was the very “instant” of appearance before our eyes and

the “situation” of movement

arising. The artist converts the exhibition setting into a “place where a situation arises” – something

made possible by an eye that detected how the space in question, ahead of its

being a “gallery,” was once an

assemblage of walls and floors, institutional choices, and various foretokens.

Consider the ways in which she has made use of the white walls of Art Sonje

Center or transformed the floors of Atelier Hermès, the high walls of this

gallery, or the space “once dubbed as the laundry room” at AVP.4 Chung Seoyoung’s exhibitions do not simply end. Double ventriloquism, the viewing

of conflicting things simultaneously, renewing the physical conditions of the

exhibition – the exhibition is a problematic time and

space where unfamiliar problems suddenly crop up.

Chung’s exhibitions force us to experience her decisions. As a moment when

the artist’s methodology coexists, the exhibition is a

world that is distinct from the outside. It is a place where we see the artist’s decisions – decisions that differentiate

her subjects, split and divide them. The objects here are physical materials

with captions such as “mixed media” and “dimensions variable,” and they also represent a dimension of “meaning” in which she provides drawings that seem to offer the occasional

hints. Chung’s capital letter “A” is minutely, endlessly divided into A’s and

A”s. Indeed, there actually are “A”s in Chung’s work:

there is her pigment print photography work A Didn’t Know B Would Do That (2014/2016) and her Table

A (2020), which consists of wood, glass, and pottery. Due to the condition

of “otherness” (B) and the

relationship of the surrounding context (the table set up by the artist), the

details of the work make it impossible for “A” to simply be an “A.” The artist controls it to the last. At the same time, the intricate

moments that she has extracted make it so that what the viewer sees is not a

splintered fragment, but rather “wholeness” as a moment grasped and temporarily set-in place by the artist.

The

aim of showing a “whole” was relegated to the background in the art of the late 20th

century. This sort of aesthetic achievement created by an artist exercising a

certain decision-making prerogative to the last was never fully manifested in

the history of contemporary Korean sculpture, with its attempts to achieve its

own form of 20th century modernist art. As the physical qualities of materials – embodied in large metal, wood, and stone sculptures – gave way over the course of the 1990s to the freedom of

indeterminacy granted by the spectacles of installation art, sculpture became

confused with installation. The original state of the material was rendered

secondary to the objective of the work and the attendant conferment of meaning.

In contrast, Chung Seoyoung emphasized an uncompromising side in her process

toward sculpture.

The decision-making authority that she exerted as an artist

inscribed the sense of “sculptureness” and “the sculptural” through a form of combat that involved increasing the bulk of the

sculpture while finely differentiating its moments. Chung’s inherent critical stance and attitude are thus the same one from

which she discussed materials, sculptures, and the moments of sculptural

emergence during the 1990s. The physical materials seen in her Knocking

Air exhibition – the white pedestals, branches,

Jesmonite and aluminum castings, and nimble stainless-steel wire – ensure that dull “meaning” does not play the role of second fiddle to the artwork.5 Her artwork and exhibition in 2020 continue to forestall the

possibility of some vague functioning of outside meaning. The kind of “seeing” that has become habitual for viewers

looking to simply glance over the world in front of them becomes impossible.

The

reason has to do with the artist’s decision-making authority. Chung Seoyoung’s

power forces the viewer to experience disparate perceptions of the part and the

whole simultaneously.6 The materials that Chung produces may appear to question all

things, but they are also firm declarations. Her work presents moments that

argue the need for ongoing adjustment of the things our eyes encounter. They

are sharp, yet also spongy. Yet viewers cannot simply let these two or more

opposing states pass; they have to choose. From the changes that arise in bland

objects like ball pens and keys to the situation in Untitled (wood,

fabric), with its origins in the artist’s 1994 exhibition – Chung Seoyoung’s work still exists as material that manifests a certain orientation

as it leaves behind evidence of its properties.

SCULPTURE’S EMERGENCE AND THE PERCEPTION OF DISTANCE

Consider

the work from the Knocking Air exhibition that consists of pedestals

and ceramic text. The characters inscribed in the ceramic on its pedestals are

lain flat. Chung’s pedestals are

not being used to effectively optimize the “viewing” experience (i.e., for display). Their painted plywood betrays that

function, with a bulk above and beyond that of a pedestal. There is also that

like a tiny bird’s nest, but the wrapping is sculpture,

and the sculpture’s wrapping is not paper (Two, 2020).

This reactive, uncompromising power in the artist’s

work modulates between paper and sculpture, the flat and the bulging, the hard

and the soft. Blood, Flesh, Bone (2019), which is located on the

first floor of the Knocking Air, is over two meters in height. It is

a “signboard” bearing the words

“blood,” “flesh,” and “bone” in

English. A vertical structure called Yellow, It (2020) has a small

rectangular mirror placed at its base. The mirror reflects different moments of

the exhibition venue atmosphere’s radiation without

sacrificing its original properties. It exists as an “it,” unintegrated with the whole.

The

uncompromising nature of the artist’s decisions gives rise to a sense of distance among the objects. The

exhibitions lack an exchange of stories among artworks or a continuous feeling

of heightening. Chung Seoyoung’s work creates a minute

separation between established conventions surrounding objects and our human

cognition. She makes sculptures, and at the same time she produces a

(perception of) distance that arises between two or more objects. Within that

distance, our field of vision narrows – then widens

again! The distance established within the exhibition setting intensifies or

disappears through the effects of time, which is the chief cause of change. At

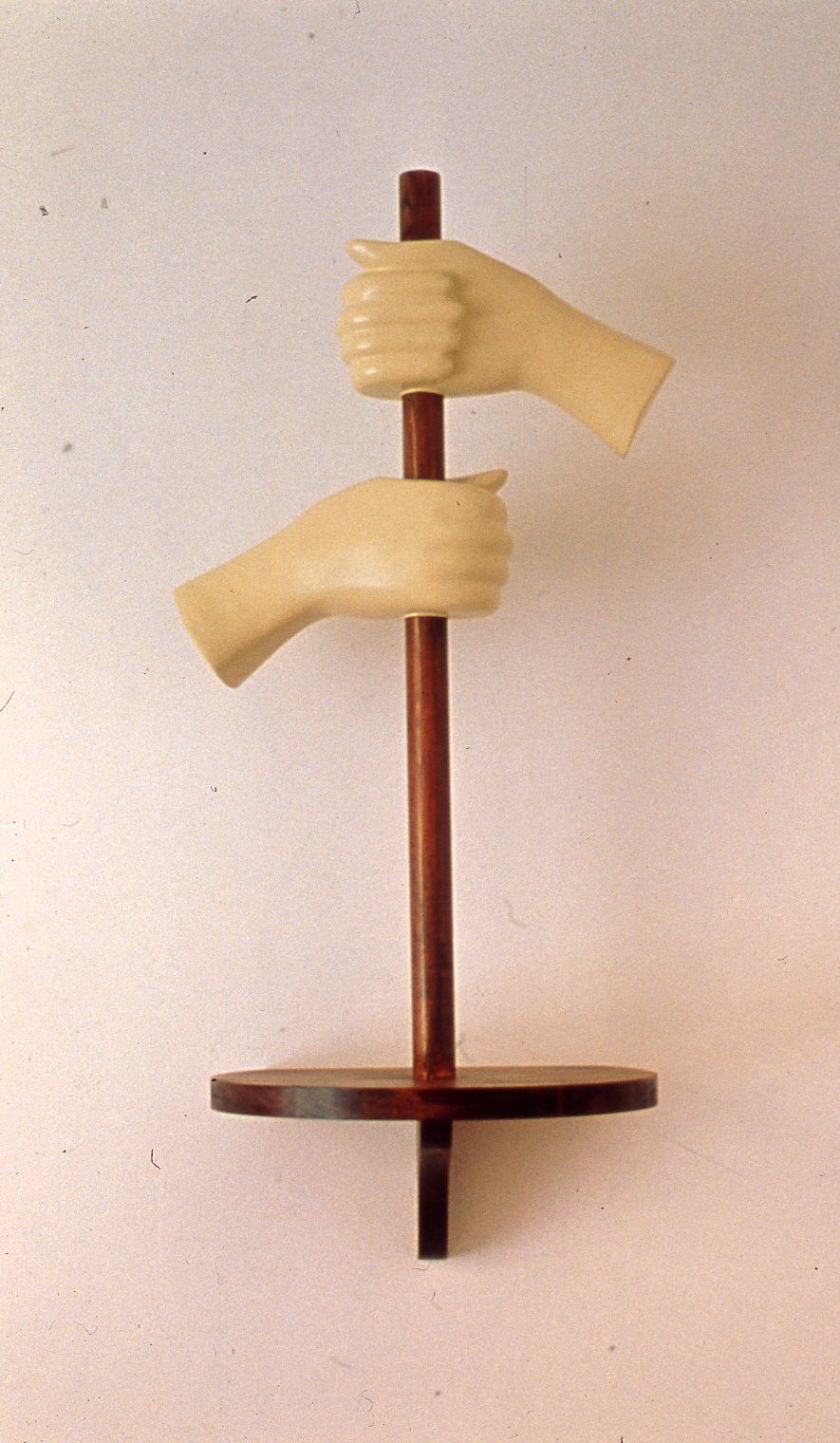

this moment, I am envisioning Chung’s works East

West South North (2007), Monster Map, 15 min. (2008), and A

Didn’t Know B Would Do That in my head. Like a

scientist holding two batons and modulating the world, the two or more objects

that she captures create a “formula for generating

distance.” If the viewers can observe the process of a

specific subject being represented or materials from the artistic process being

combined, they will perceive the artist’s work as less

difficult. In Chung Seoyoung’s work, however, there is

a “path” that is formed through

the process. It is a path that changes anew when we stand in front of the work,

one densely woven with limitless possibilities for surveying in new ways the

relationship between reality and artwork. If we view Chung’s sculpture through the lens of the dictum that “a path is a line whose beginning and end are distinguished,”7 then it generates a different power and tempo “on its own” each time.8

Chung

Seoyoung’s sculptures change with the surrounding

atmosphere, the viewer, and the movements of the world itself. Her sculptures

are not objects attributable to some change in this case, but dynamic subjects

that appear as unpersonified “things.” Recall how wheels (East West South North) and footsteps around a

neighborhood (Monster Map, 15 min.) have been used as part of her work. In

referring to the “beginnings”

and “endings” that surround

movement, one may think of Table A from the Knocking

Air exhibition. Its strange road seems like a “mass

of hand” combining both a left and right hand, or an

architectural structure stripped of its sense of tempo; it recalls an isolated

village that repudiates the very aim behind a path’s

emergence. It is also an exhibition that illustrates collection, juxtaposition,

and temporary coexistence, in the sense of having different things positioned

within a single space (on top of the table).

Seeming as though it might be

occupied by vague clues of indeterminate beginning or end, the work actually

proceeds in the opposite direction, becoming quite lucid indeed through the

author’s narration. “The

different sculptures have actually come together to form the table after being

thrust out by some unseen reason,” she explained. There

is something both interesting and important to note here, namely that the

artist’s explanation of the reason for the artwork

manifesting itself in its current form calls to mind innumerable “possibilities” prior to its completion,

rather than the current outcome. The presence of objects that harbor the

potential for different directions of movement appears before us as the product

of a differentiated combat. By emphasizing the “process” of these forms – at a time when we could

not yet predict what they might become – the work

establishes its own grounds for existence.

How

does the artist transport things that she witnessed with her eyes into actual

evidence? Chung’s process is

exceedingly independent in the way it rejects references that would be

secondary to the work itself. It problematizes the process whereby shapes

become “specific shapes.” The

Same (2020), which is located on the second floor of the Knocking

Air exhibition, is unquestionably an important work in our discussion of “exhibitions,” being a mechanism through

which Chung trenchantly addresses her own decision-making authority and

time. The Same begins out of the disappearance of once-certain

evidence, namely a 1997 photograph the artist took at her studio, which showed

a “small sculpture I had sort of made and then pushed

aside.” She uses the “installation

view” – a device for recording exhibitions and

mediating with the present – as an opportunity to

re-encounter a sculpture she had cast aside a long time before. Vanished

objects that had once been placed before her but had since been substituted

with something barely visible (a chanced-upon photograph) became sculptures

once again. This is the result of the artist attempting to shift and push

through the gap between lost time and the sculpture through which she is able

to create “it” again. Her

sculpture surfaces and disappears again in defiance of the linear

(horizontal/vertical) flow of time, harmonizing with the surrounding air,

sound, and light.

EXHIBITION

TIME

Let

us now consider the “exhibition time” that Chung Seoyoung called to mind for me. One of Chung’s accomplishments in Korean contemporary art has been to imbue time

into sculpture. In her sculptures, she has created not “form,” but “being.” This bears some relations to the invisible time that is “unconnected” with utility amidst the period

of the time of the dynamic industrialization process and democracy, with its

excessive pressure and emphasis on speed. Chung’s

sculptures distance themselves from the monumental qualities of masculine

modernist sculpture – their knocking, standing,

raising, stacking, and dividing. As she has emphasized, she strives to minutely

narrow down the questions that determine the “form” visible to the eye. Her sculptures are the evidence of time spent

shattering established preconceptions about sculpting from the mid to late 20th

century. Chung is confronting abstract time itself; she is addressing the world

as a whole.

There

are several time axis that we must trace. If what we are viewing is the time

axis at the level of the reality of the Republic of Korea since the 1990s, then

the materials – the plastic, plywood, sky

blue paint, resin, and so forth – may follow suit in

asserting their own “times.”9 Another issue concerns the stature of the exhibition’s own time. Chung has attempted to expand the very time surrounding

the exhibition to the pages of a leaflet – not simply

the opening and closing dates of the exhibition venue, or a viewing time that

relates to the exhibition course for the viewer or the connections among

artworks.10 The aim of this expansion is not expansion per se, and its

attendant broadening of volume; Chung is establishing a field of vision for

reexamining a preexisting tacit agreement. It is a lucid argument. The work

that the artist has positioned inside the exhibition becomes something

performative, varying its methods of emergence to suit the corresponding

spatial and temporal conditions.

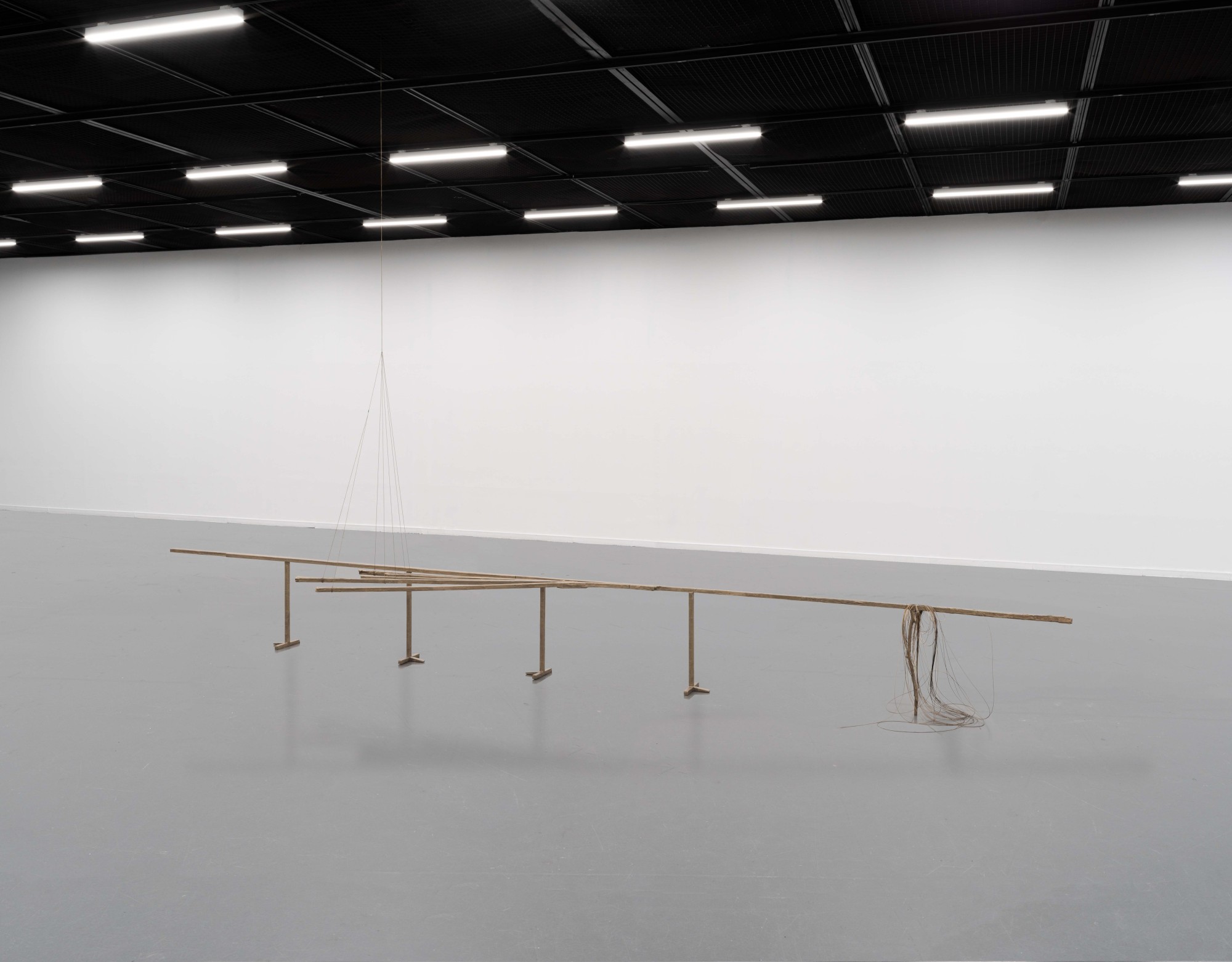

For instance, Monster Map, 15 min.– one of Chung’s works that has involved

different media, such as drawing and performance – also

serves as a score “directing”

its exhibition. At one point, Monster Map, 15 min. transformed into

another work called Green Here and Green Yesterday (2016), which

corresponded to the AVP laundry room. Applying the Monster Map, 15

min. methodology to the AVP space that was “once

called the laundry room,” Chung sculpted the “situational space” that was Green Here

and Green Yesterday. Without the use of any separate fixation devices, the

bough was adjusted to suit a rectangular space possessing volume. Long,

tautly-spread bough sharply cut across that space.

Chung

uses exhibitions to determine the existence of her sculptures and the path of

viewing. The exhibition allows the work to change and reemerge. The artist’s reference to the “pale light of the

gallery” at the time of her 2000 solo

exhibition Lookout (Art Sonje Center) shows that the object she

sought to view in detail and control was the very reality of Korea, which was

something that could not be encompassed through the limited institution that is

“art.”11 Her methods in venturing inside a temporary model house

space to display her work in the Apple vs. Banana (an old model house

in the basement of Hyundai Cultural Center, Kim Kim Gallery, 2011), or in using

evidence from past works to recall the moment at which they became sculptures,

signify again that what she is focusing on is not only the exhibition in the

narrow sense originating from the context of contemporary art, but also the “exhibition” as the presentation of a world

in the broader sense. She sculpts “exhibitions” in the sense of “moments when an object

becomes visible to the eyes.” Chung applies a power

that determines not only the “moment when an object

becomes sculpture,” but also the temporal and spatial

circumstances. Through the exhibition of sculptures that manifest within

specific times and places, and through the opening-up of the vision behind the

creation of an artist’s solo exhibition, she

contemplates the “ways of seeing” the world.

Chung’s sculptures exist within the flow of time. She does not overproduce

materials or objects. The time of viewing her sculpture is added to the time it

takes for one to be produced. Once the exhibition as process-of-display is

completed, the time continues with the work being left behind in a different

set of circumstances. Chung’s ability to sculpt objects

without the use of violent verbs such as “smashing” or “hacking” stems

from her focus, which is on the endless motion of relationships surrounding the

sculpture and the world. Like the self-standing sculpture Blood, Flesh,

Bone, her objects are independent in the sense that they stand upon the ground,

viewing their own demise – independent ghosts.

An

exhibition is time-limited. Chung Seoyoung’s exhibitions capture fixed moments in a way that doesn’t stick, like taking a mold. She intricately sculpts momentary

circumstances. What she holds in her hand is not a weapon-as-tool (the

materials of making); she is confronting traces that remain as nothing, or

facing the vastness of the world itself. Chung’s

sculptures are “unending”

works, which have the ghostly quality of being alive while seeming dead. One

perceives the spirit inhabiting the formativeness, rendered as abstraction with

the bearing of the strict formalist. In addition, her objects bear modernized

animist properties. Objects that give off their own power appear poised to

travel outside even as they remain stationary; the realm of secularized reality

takes on the appearance of a sublime jewel, like the walnut that appears in her

video work The World (2019).

The exhibition setting that Chung has so

carefully organized has sometimes existed in the form of display as “atmosphere,”12 but over time it has become a variable rather than fixed

condition for the artist, giving rise to a “situation” and performance. Chung has said, “(The process of preparing the two exhibitions you mentioned) was fun

for me as it turned into a situation drama in each case; my thoughts

materialize into objects, and the objects thus created induced movements.”13 Due to the artist’s unconventional qualities, that direction leading from “idea” to “object” to “movement” is

not repeated at a definable speed. Times and spaces that flow in unpredictable

directions are incorporated as situations inherent to her sculpture.

In

her work, Chung goes beyond things that are proper to a particular era,

approaching installations in exhibitions that are situation-specific at every

moment. With her approach of touching on countless representational statements,

her sculptures may be said to be situated amid the interstices of the acts of

whittling and kneading and shaping. This situation-specificity lays bare the

impossibility of fixing a world in place through a single language or object.

The “flowing time” that Chung

often speaks of is not the opposite of “fixed time.” As I was finishing this piece, I saw the artist’s Light from a Bicycle (2007) at an exhibition of items

from the collection of the Gwacheon branch of the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Korea. There was the bicycle-as-object, the light giving off

its beams, and a gallery wall to one side with a hole bored in it. The large

false wall used to produce the small hole is both part of the work and a

visualization of the excessive desolation and physical languor of the

exhibition setting. The light travels as a focused beam through the hole.

The

sculptures in Chung Seoyoung’s Knocking

Air exhibition are produced in such a way as to strip away the excess as

they reposition themselves down to their very framework. The artist’s work presents moments in such a way that “it” exists as “it,” and

the core as the core alone. The unpredictability, the simultaneous viewing of

different things, and the decision-making authority that narrows down the

pathways amid the battle – these represent arguments as

artistic language. The time of the exhibitions that Chung makes – or, more concretely, sculpts – clears away

a blind alley of seeing as an act. Consisting of the artist’s condensed choices, the path possesses a characteristically

hermetic quality, a more trenchant form of completeness. This is something has

been difficult to find in contemporary reality, which had appeared to be

endlessly expanding. Chung’s sculptures present the

whole of great concepts that were fading into oblivion – very concretely, or in detail. It is something that encompasses an

abstract world in and of itself.

Chung

Seoyoung’s work leads me to believe that there is a field

of vision that arises merely though facing an object. It is still very

important to us that we are led to harbor such expectations. Like the laws that

govern objects, which like steam and ice proceed toward an inherent condensed

state as the atmosphere changes, Chung’s sculptures

draw the viewer before them as core moments – creating

bodies for formless speech, texts, ideas, and being. As they create a sense of

distance, they walk and stop, looking simultaneously forward and backward.

After their brief rest before a given time, her decisions will venture off down

a different path.

- “Hopefully,

the piece created by this strange and preposterous combination could be

made to be able to predict the time that does not stay as it is in any

direction and flow ahead”. This text was written

about Bone and Walnut (2016) for the 2016 Audio Visual Pavilion

exhibition Chung Seoyoung. Quotes in the current piece that do not

include other bibliographic information were taken from the artist’s notes.

- Chung

Seoyoung, Chung Seoyoung, excerpt from the brochure

describing Wave.

- The

sentence is the artist’s response

to the question, “Are you a sculptor?”, Kim Hyunjin, Chung Seoyoung, “An

Interview with Chung Seoyoung of Ms.C,” The

Speed of the Large, the Small, and the Wide, Hyunsil Books, 2012, p.

139.

- “Place once

dubbed the laundry room” is a phrase used in the

artist’s notes and conversations with her during

preparations for her 2016 AVP exhibition.

- Chung

Seoyoung’s work seems to

possess an inviolable realm of artistic language that makes associations

possible without offering conclusions or symbols. Consider a critique of

her work from Lookout, her 2000 solo exhibition at Art Sonje Center.

The art historian Nanji Yoon wrote, “What she

hates, is not depth, but the terms that go with it.” Yoon also wrote, “She creates two

flowers out of squeezed sponges, and sculpts waves with the craft of a

traditional sculptor.” Nanji Yoon, “Hating ‘Depth’:

Reverse Perspective in the Work of Chung Seoyoung,” Lookout, Art Sonje Center, 2000, p. 17.

- Let’s toss out a few perceptions from Knocking Air. Piercing

yet frail. Weighty yet light. Slipping yet firm-backed. Halted yet in

motion. Moving vertically and horizontally yet within a circle. Within the

exhibition, the viewer constantly follows the signposts erected by Chung,

hoping to encounter a visual declaration. But within the coldness of

dividing, simultaneous perceptions, senses explode yet are isolated. Both

the sculptures and the viewers are moving toward the state

of jeongsu – a Korean word meaning “essence,” but with the dictionary

definition of “marrow.”

- Charles

Sanders Peirce, Peirce on Signs, Korean translation by Dongsik Kim

& Yuseon Lee, p. 294.

- The “on its own” and “tempo” here come from the writings of

curator Hyunjin Kim (“Objects and Language That

Shine and Vibrate on Their Own,” Art in

Culture, January 2008; “Chung Seoyoung’s Words and Objects: The Density of Ambiguity and Shining

Clarity,” The Speed of the Large, the Small,

and the Wide, Hyunsil Books, 2013, pp. 222–234.

- One

may also juxtapose the relationships in Chung’s work – which has employed Korea’s visual exteriors as material along with Styrofoam, linoleum,

plywood, and so forth – with the writings of the

sociologist Suk-Jung Han. Describing the military administration of 1960s

South Korea as a “regime that conspicuously

displayed masculinity with its swift penetrating and digging and filling

and covering up,” Han writes, “The reconstruction system vaunted its presence by developing

rugged terrain and exalting command over nature, transforming spaces with

simplicity, straight lines, rectangles, and vastness. Underlying this

pursuit of development, its speed, and the linear construction was a high

modern spirit that had flowed over from Manchuria.” Words such as “penetrating,” “filling,” “digging,” and “speed”

are used as headings in Chapter 5 (“The

Construction Era”) of Manchu Modern: Origins

of the South Korean Development Regime of the 1960s, Moonji, 2012, p.

297.

- Connect 1: Still Acts* (Art Sonje Center, Nov. 5, 2016). Quote from Chung Seoyoung during an artist talk program for the 2016 exhibition.

- This

brief interview with a weekly is also interesting in providing a rare

evidence of Chung’s humorous

side throughout: “The gallery’s lighting was changed to white, because it made the works look

more ‘languorous’

underneath the pale light. The artist was still disappointed. ‘The fluorescent lighting is fine,’ she

said. The reason was that the yellow light in the gallery made the

sculptures look ‘artistic’

(expensive).” “Making Fun of ‘Sacred Art,’” Weekly Dong-A, Vol.

229, 2000, p. 90.

- Commenting

on The Work Made from Several Tens of Drawings and Some

Sculptures (1994), the artist Chan-kyong Park wrote that “the assemblage of objects is an outcome(display) that is an ‘atmosphere’” and “atmosphere (…) is appropriate to alert

us to the fact that the world where objects exist is ambiguous.” Chan-kyong Park, “Lookout; The Objects

of Chung Seoyoung,” Lookout, Art Sonje

Center, 2000, p. 7.

- Interview

with the artist. Sungwon Kim, On Top of the Table, Please Use

Ordinary Nails with Small Head. Do Not Use Screw, Atelier Hermès, 2007, p.

79.