The

work of Chung Seoyoung asks fundamental questions: Can you do sculpture without

doing it? Is the life of objects independent of the materials from which they

are made? Are the forms and objects made by an artist sensical or absurd? Is

there a correlation between all the objects that exist? Appearing carefully

arranged, the thirty-three works presented at the artist’s semi-retrospective What I Saw Today in Seoul Museum of

Art (SeMA) could be seen as much more than an exhibition of her works, but as

an opportunity for all those works to be together and in the de-sublimating

manner of Chung’s philosophy –

activate our senses for future interpretations on objecthood and space in an

environment informed by conspicuous consumption and material cultures. For

instance, despite the artisanry that went into their fabrication, the works

transmit their industrial origins. The exhibition could be seen as a work by

Chung, a piece in which she addresses the mutable sociality of every material

and form she has created over the last three decades.

Figures

becoming forms, forms scaping figures

When

you encounter the work of Chung Seoyoung in the exhibition at SeMA, there is a

noticeable tension between figure and abstraction. The figures and forms of

each work – some of them naturalistic – stay in tension versus the form created by the whole composition of

the exhibition. The “exhibition” is an abstract notion and yet in seeing the works of Chung together

we are under the impression that all the works have long been waiting to be

part of What I Saw Today. It is legitimate to ask: is the exhibition a

work in itself? The way that Chung invites her works into the space possesses a

very powerful eloquence, and, for a second, we are tempted to see all as a new

large-scale installation, a new piece.

The works have found their place in the

space, so it is demanding for us to teach our senses to go back to every work,

to focus on every form, and to analyze the conditions that make each figure

emerge. And in this manner, we understand that for the artist sculpture is the

task of undoing the figure, of undoing sculpture itself. This tension indicates

that there is something else out there an artist needs to get to and that the

act of trying is what constitutes the practice even if one may never reach it.

Yes, the work of Chung implies that the making of sculpture entails a radical

re-positioning of one’s interpretative perspective of

the world we are in. Time; time and materials; time and materials and

experience; time, materials, experience, and thought …

All these dimensions collide in her works. This collision obliges us to start

reflecting.

A wonderful way of seeing how Chung Seoyoung works out this tension is in her

work Wave (a remaining part of the installation work Ghost,

Wave, Fire, 1998–2022). The original plasticine work

has been recast into Jesmonite for the solo exhibition What I Saw Today.

How many waves are there in the ocean? Do all waves have a wave form? Or are

they just wind-and-water and, therefore, there is no such form as the form of a

wave? And yet the oceans are inhabited by the figures of waves, trillions of

waves. Wave modeling has been a subject of interest to a vast range of

characters, from ancient painters to oceanographers, mathematicians, and

meteorologists pertaining to both indigenous and coastal communities and

Western scientific ones. Why so? Because a holistic – a

global – state of the sea can often be illumined

through measures of its smallest component: a wave.

A wave, like a flame, has

never the same shape or figure, and therefore it possesses no form. It is only

a transient substance that constantly changes because of the factors that

affect it: the wind, the body mass of the ocean, and the heat in the case of

fire. For that reason, to do a work – a sculpture of a

wave – is like negating sculpture and waves, since for

it to be a wave it needs to be able to continue to change, oscillate, and have

its crest go down to the ocean to come up again, and again, and again. What is

then, the wave? Inside this wave are all the waves and the whole Earth as it

was originally made of clay. But later on, now, it is reproduced with a newly

invented material: Jesmonite, a combination of gypsum (a mineral created from

sedimentary rocks) and water-based acrylic resin. In this sense, this wave

embodies all climate futures, environments, and narratives that nature-culture

created to address the wisdom and miseries of our species in relation to our

planet.

Doing a wave makes us reflect on “limbic” experiences and emotions: experiences and feelings that form a

border around them. In seeing this wave, we want its energy to be maintained

and wish that this individual wave would not disappear into the ocean. This

wish has a primordial function in culture. It relates to our aspiration to keep

control of everything. In this sense, the wave offers us guidance to understand

this emotion and, also, to find a place for it within this work.

Models

Take Sink, a work from 2011. An existing sink, originally part of a model

house, has now been re-arranged and presented as a work. A part of the piece is

situated on top of four rocks. The question of the model has been haunting

sculpture forever. And the best way to collapse this question of things that

resemble other things is by granting another life to the original things. In

the case of this piece, the question of the model goes into deeper trouble: the

sink belongs to a model house. A model house is a house that shows you how to

use a space exemplarily, it performs the fantasy of the best living practice.

Those spaces not only embody the norms of a certain society but also dramatize

them, creating a scenario for our happy co-existence inside those norms and

values. The space becomes the scenario in which we inscribe ourselves living

there for a few minutes, for a short while. That model sink was a part of this

model living. It was perceived and viewed inside that context of desire, it was

performing a moment of our lives where we wish we could be at home there, using

it, cleaning the plates that feed our loved ones. But it also performs all the

tensions of accepting this invitation and renouncing another life or lives that

have no place in this model place.

Actually, the problem with this sink is not that it is not real enough, but

that it is too real. Models of objects, rooms, and whole houses portray best

practices and uses while, at the same time, embodying a canonical approach to

life in those spaces with those objects. That’s probably why in the second life of this sink, there is a part,

which rests on top of four rocks. Rocks are never models. We only notice this

fact when we see them co-existing with an object produced by humans. A rock is

never a model of another rock or a mountain. Rocks sustaining a part of a model

sink on top are presenting two very different dimensions of time being simply

together.

The sink synchs with culture, with a culturally produced behavior,

with its norms and expectations. The rocks here add to the scene a sense of

time that has nothing to do with the biological time that determines the

finitude of all living creatures. It is true, our worlds lie upon the worlds of

nature and its laws. How many of these living models does a rock remember?

Stones, all through their geological lives, may have witnessed plenty of living

models, plenty of attempts to make matter do what we humans want.

Analogies

Analogies are very present in the working method of Chung Seoyoung (and so is

pain). In The Body in Pain, literary scholar Elaine Scarry begins with an

examination of the pre-articulate and private nature of pain – verbally inexpressible and yet absolutely certain for the one

experiencing it.2 After the pain, victims may offer analogies such as, “it was like a flame,” or “it was like a knife.” Scarry refers here to

the immediate incommunicability of pain as the locus for the destruction of

worlds. The work of Chung Seoyoung seems to see immense potential in the

destruction of worlds – and the pain – originated by fast capitalism. The frequent episodes of economic

collapse and recovery that society has been through leave traces in the social

and material cultures of a given community – and South Korea

is not an exception.

Chung’s work emanates a sense of

responsibility toward this transformation. The question of pain and loss (the

loss of traditions, materials, and ancient knowledge) is replaced with the need

to produce a dynamic method able to act and infuse energy into the materials

that exist under such conditions. The method, at first, is difficult to grasp

because of the subtility of the craftmanship and synthetic arrangement of the

formal elements, but it eventually breaks through, reshaping our perception and

igniting the emergence of other-than-capitalist values and behaviors. This is

one of the main impressions we get from Chung’s

exhibition.

Take, for example, Ice-Cream Refrigerator and Cake

Refrigerator (2007). Both look like ice refrigerators but there is no

point in comparing the actual ones that are in small convenience stores in the

streets of South Korea to the ones in the exhibition. They are simply related,

in pain and painful joy. These forms convey the persuasiveness behind an exploration

of embodied experience from the point of view of the objects, of the material

artifacts that usually contain ice cream: a certain type of capitalistically

produced, sweet happiness. Ice-Cream Refrigerator and Cake

Refrigerator omits the real refrigerator and yet the “real” is immediately perceived as the

obvious foundation of the work, the source, the origin. In her whole practice – so well unfolded in the exhibition What I Saw Today – she induces a discernment on how an “understanding” of a thing can be made by making use of another thing, and how an

understanding of materials works in the same way. And so, she also creates a

flow of shifting emotions from familiar objects and materials to their new

situations and lives.

But another interesting trait of analogies is that they tend to offer

oversimplifications. This is one of the most beautiful characteristics of the

philosophy and epistemology Chung sets at play: in her work, she produces a new

ground for all her objects, an ambiguity, which slowly makes us understand how

she has been through the years freeing her works from the conditions and even

the material culture they stem from.

Rhythms

To Clean Up Once a Year (2007) is a work made of cement and an artificial

plant. It seems at first the product of a surreal dream. Chung Seoyoung’s work can be read as an ongoing process of documentation, which

manifests itself in and through objects. Nature appears here already as a

spectrum, it seems to be here, but it is not. This plant is artificial, and so

is cement. Both entities are made. None of them has their real origin outside

the realm of humans. What is the work documenting? Ways of dealing with

production and how to re-animate dead matter. In the Western Romantic

tradition, one could say that she reaches the possibility of elevating inner

matter into a critical and epistemological realm. But this is through a careful

and deep understanding of the role of rhythm and not formal beauty – like in the Romantic tradition – which is

something that happens in Chung’s work.

Rhythm is a question that defines the relationship we establish with the real.

If the real possesses rhythm, we assume life. If the real is dispossessed of

rhythm, we assume inertness, lifeless matter. However, already around 1800,

poets such as Novalis started doubting this binary. The discourse around rhythm

emerged then to account for matter’s property that

never remains the self-same. For example, biological matter changes every

second – cells divide and even change – without us even noticing. However, over time, changes appear and we

are able to detect that those changes occur sequentially, and rhythmically. But

inorganic matter is also affected by a play of change. This reflection on

rhythm, as a property, which affects all that is around us, creates relations

and forces capable of producing dynamic winds. And these dynamic energies came

late to the world of philosophy.

In the West, French philosopher Gaston

Bachelard, and later Henri Lefebvre, were the first to pay attention to the

concept of rhythm, a notion important to understand time in a philosophical

context.3 Rhythm slowly arose as a concept different from duration.

Rhythm presents time not only as a continuous state but also as that which

contains tension perceivable when certain discontinuities appear. In Chung’s practice, a material that exists and has a life outside of art is

suddenly used to produce a work of art. Here its continuous life as an

industrial material, for example, is disrupted and another life, which embeds

another sense of time, emerges. The artist’s

methodology adds to the temporal life of normal matter the symbolic dimension

of time that art embodies. Her works reflect those temporal tensions.

Time is not seen as a fact, as a calm flow, or as a continuous state, which

simply happens to us or to things. Time in Chung’s

practice and works is the result of an infinite oscillation between continuity

and discontinuity that happens inside a work. Rhythm helps us to understand

that inorganic matter is sensitive to the specific connections an artist

establishes with it in giving it a form, giving it a place in the world, in

relating the work with other works – like in the case

of an exhibition such as What I Saw Today. We can say that rhythm makes us

aware that life is not a condition of organic beings, of biology, but a

condition we share with all that exists in the world. In the work of Chung

Seoyoung, rhythm, dynamic energies, and a non-static experience of the real are

very present. The work reminds us that not only humans are conscious of the

existence of things, of an object. But also, objects know about the life they

have been living in, about the contexts they have been exposed to.4

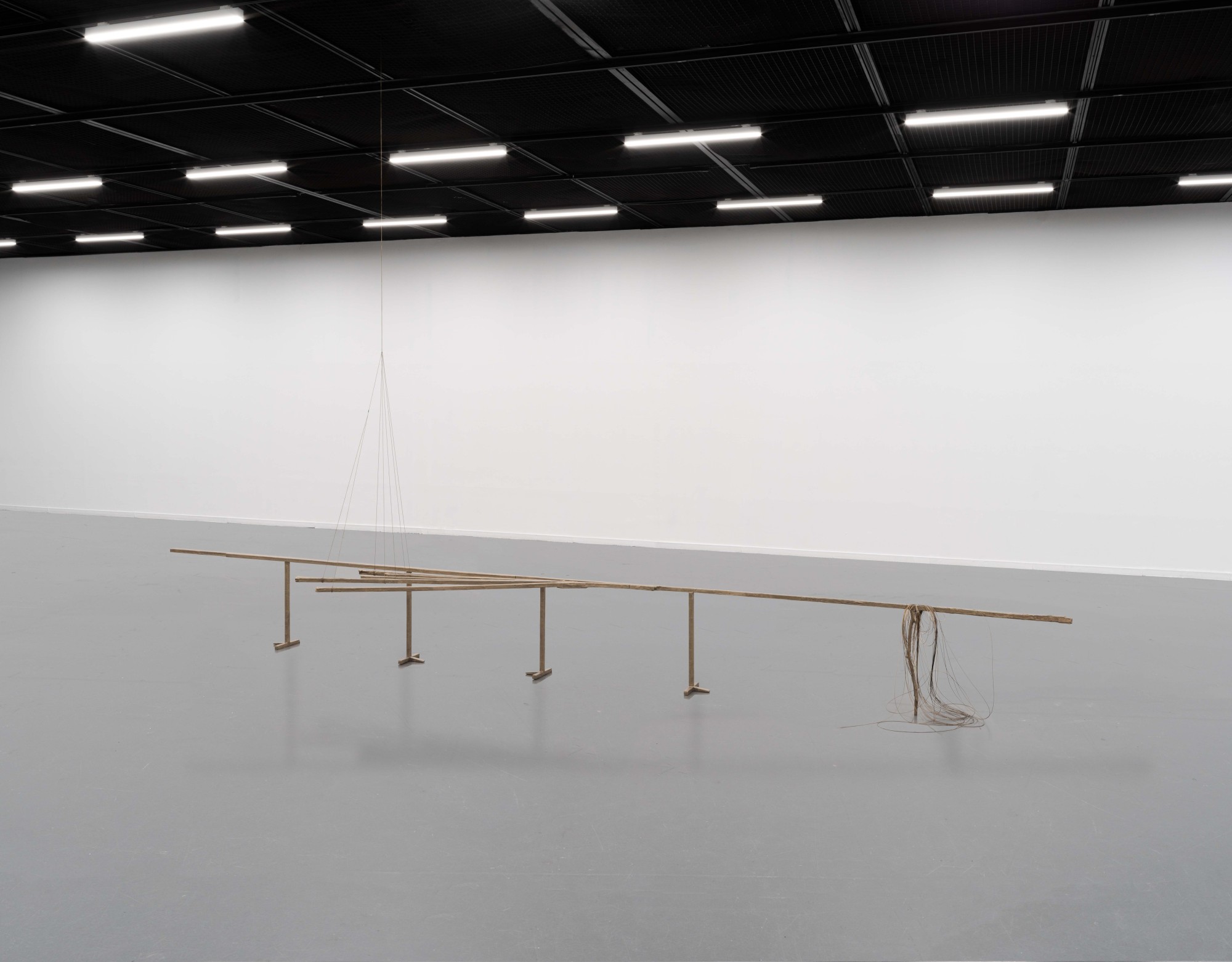

The Time Is Now (2012), where desks are placed (or displaced) on four

wooden trestles and several pieces of wood assist in keeping the balance

between these elements. A working desk, a desk where you were supposed to sit

down and work. On top of the desks, is a large sheet of glass, and below, the

trestles. A desk’s function

cannot be performed. The desk is synchronized with the thousands of desks at

which the desk workers of the world work. Now, one cannot perform. It is still

a desk, but more of a ballerina elevated in the air with the simple help of

those thin wooden legs. Up in the air, it can probably observe other desks

occupied by all those humans sitting in front for long hours. Desks and Fordist

capitalism are the subjects of many books, but I would say, a desk elevated

like this deserves a poem.

A desk on wooden legs exposes the contrast between

the desks oriented to support production in large-scale Fordist factories

versus the studio and home desks supporting creative labor. And so, one can say

desks also speak about male versus female work. Desks are gender markers. While

adult men have entered the factories en masse, only a small proportion of women

did so. The desk surface is the flat scenario of a social conflict, of a

specific form of labor that stays in opposition to field labor, unpaid domestic

labor, and the creative tasks performed on the tables of the studio by an

artist.

Fires

– and the imagination of matter

Campfire, a work from 2005, portrays a fire in the color blue. Fire is orange

and red and yellow and blue. But here, it is only blue. Could fire imagine

itself being different from what we believe it is? Fire, like water, belongs to

the elements that, in simple terms, explain the materiality of Earth. The work

of Chung Seoyoung is both philosophical and embodying poetics: while her works

demonstrate the need for systematization associated with rational thought, she

also insists on the collapse of any system in the face of an infinite richness

of experience. And experience is here to be understood as a deep experience,

one that is not satisfied on the surface of perception. Her notion of

experience demands an attempt to circumscribe existence with a profound

imagination – imbued with poetic experience – that transcends an individual imagination of a subject. That’s why the fire is blue. The birth of fire in human history as well

as the constant analogies of the libidinal components represented by fire gain

here an almost comic-like, humorous dimension: a blue, bubble-formed campfire.

Campfires are associated with youth culture, a certain moment in life in which

the mastery of fire is associated with the impulse to urinate on the flame to

extinguish it.

Like in many other works, Campfire becomes an opportunity for a

creative daydream where our mind oscillates between different possibilities and

scenarios the pieces may emerge from. A campfire is a primordial fire, the

first fire that ever gave … She first activates our

desire to “bracket” the work

and see it as alone, unique, and separated from her other works; then she

awakes in us the aspiration to apprehend its entirety inside her whole

practice. This calculated method could be called: the awakening of the creative

epiphany of an image. Chung’s poetics result from her

cross-fertilization of the general epistemologies at work in common objects

onto her metaphysic of the imagination of materials. Chung does imagine matter

imagining, dreaming, willing, and wanting. Matter is transformed not only by

industries or artists but also by itself. Matter possesses agency and this is

the energy that she rescues and channels in all her wonderful works.

Airy

solids

Words in the Flesh (2022) is a work on the floor where salt and wood glue

are directly applied to create a salt stain. Salt remains in the absence of

water, and yet we cannot but think of water when we see the piece. I once heard

marine biologist Diva Amon praising the centrality of salt in all creatures’ life.5 Salt is a mineral that entered the history of human life

since we are unable to live without it and yet salt water, like in this work by

Chung Seoyoung, is like the ocean, which can never be a source to calm our

thirst. Salt routes, salt mines, salt rituals, and salt religions – it is impossible not to think, at least for a moment, about all

those dimensions. Yet this piece – probably because of

its nearness to another work that is made of stainless steel wire, An

Ordinary Day (2022) – refers less to nature and

more to the possibility of adding a mineral layer to the exhibition. It gives

the impression of a leak, an accident, a pipe or an infrastructure unable to

perform causing an undesired trace on the floor. A trace always makes us go on

in our minds and create a story around their presence. Think about animal

tracks: when we see the paws on the ground of a field or the snow, we

immediately wonder about when. When was the animal there? When did the water

abandon the ground allowing the salt to remain seen?

This work will never

happen again in the same manner. It has a past and a future that will always be

different. Our mind, though, is very limited and cannot follow all these

processes with a vivid and detailed imagination of the many becomings the work

went through till it was dried and fixed to the floor. Our perception tends to

produce an isolated consciousness of processes and reduce change to a stable

form or state. We assume the important element of this work is salt – and glue – but it may be water that is

crucial, although is now absent. The relationship between what is there – and the random form salt and glue adopted on the floor – and what is not there forms the myth in this work. The myth is

always a story that reflects and revolves around the possibility of something

missing to return. A disappearance – here simply water,

one of the most fundamental elements of all that exists – can be imagined to return just in seeing the salt flakes on the

floor.

And talking about the creation of mythical energies, near that piece, hanging

from the wall is the work An Ordinary Day, made in stainless steel wire.

Steel wire carefully hand-produced poses a difficulty to vision. It is visible

but its faint color and material against the whiteness of the exhibition space

and the air pose difficulties for our eyes to fully grasp the details of the

piece. Like the salt on the floor, its form seems eager to escape our efforts

to fully retain it in our minds. Steel wire is solid, its form will not so

easily change, like salt. But An Ordinary Day leaves us under the

impression that every single thread has been separated from the steel plate in

a very laborious way, turning the original plate into hair, breaking the

continuous metal surface into single fibers as if they were combed and ready

for a future spinning. A material suddenly reminds us of something else, as if

metal could forget itself and become wool … Forming

presence is forming absence. This way we expand our imagination of the work

because we see more than what is there. Also, memory stops being a passive

function that recalls a past or a fact. Memory actively reconstructs the state

of the piece before the piece took its actual form, a stain of salt, a bundle

of wire. The game between the work and non-work makes us realize that the

non-piece comes into being through disappearance.

Organs

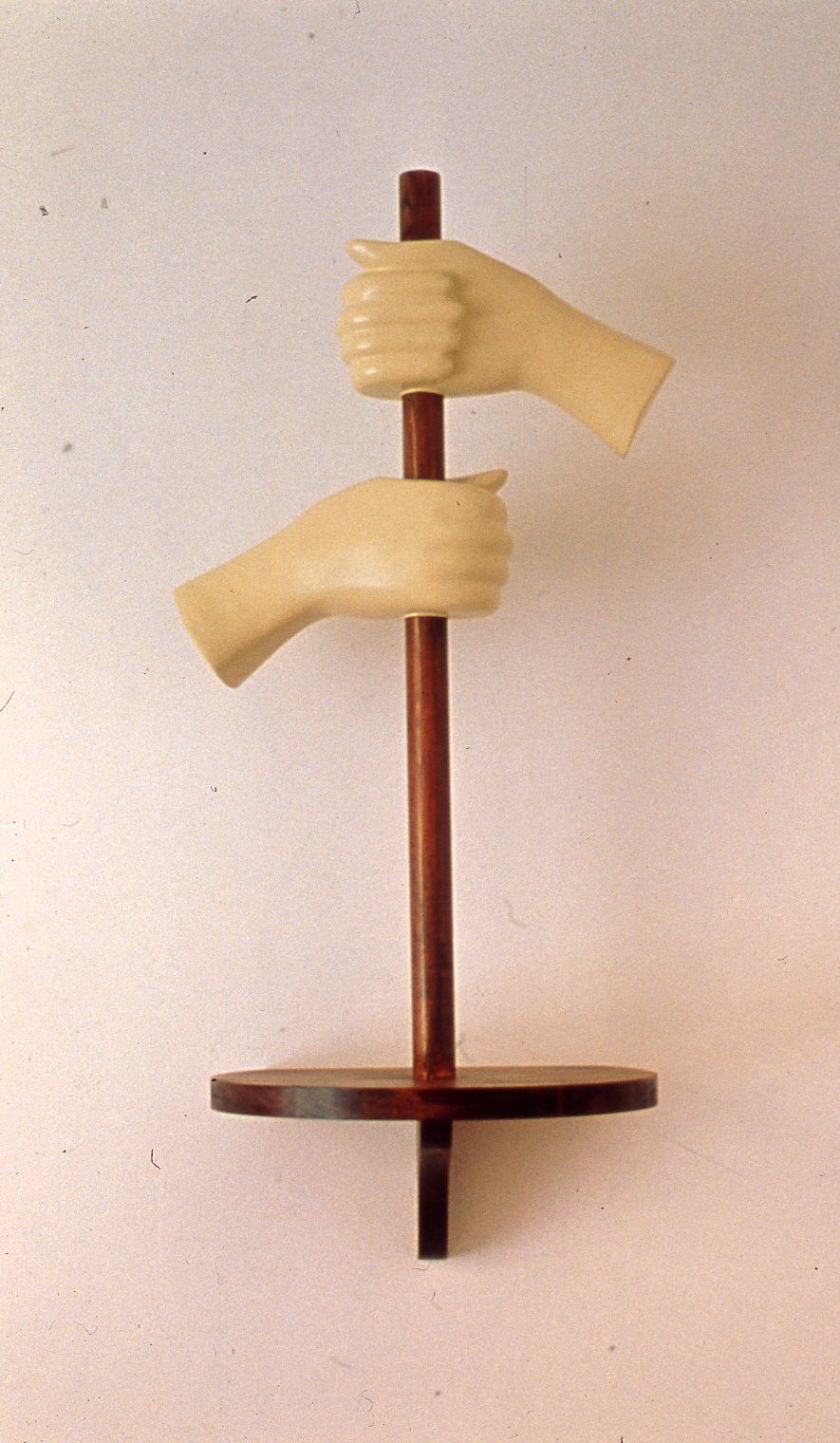

Carl

Sagan said, “The brain is like a muscle.”6 If we accept that premise, we would need to find a bone to

give that muscle support. Chung Seoyoung has built that bone through her very

recent work, A Bone in the Brain (2022). First, it was an ensemble of

thin wood, nothing very solid, nothing very permanent. A form that reminds one

a little of a tree, or a plant. Then, that wood structure was transferred into

bronze, gaining a different strength. It brings to mind a ballet barre, at

first sight. Thinking about it, this image goes well with the title, A Bone

in the Brain. The barre was invented to support dancers performing a series of

protocol movements to discipline their bodies and posture. It is known as the

instrument that trains inexperienced dancers in the art of balance.

However, this barre, this thin, almost improvised, tree-like trunk

needs assistance itself since five branch-like arms have grown out of it. The

bodily expansion may have been an ambitious move, as it puts the entire work’s balance at risk.

And, indeed, the five branches are attached to

wires that connect to the ceiling to avoid the piece from losing its stability

and falling. Some extra wire is hanging at one end of the sculpture, as if more

wire assistance may be required in the near future. On one hand, the golden

patina of the piece somehow surprises us. The gold undertones a sense of

lightness, and also, warmth. As if the whole trial –

pursuing to give the brain a bone – was something that

could be realized with very simple means. But the golden color adds a symbolic

resonance: it refers to the material we know, wood, but now that it is

transferred in bronze with a golden patina it transcends its original precarity

and emanates durability. The piece has been self-accomplished in finding this

form after a long search.

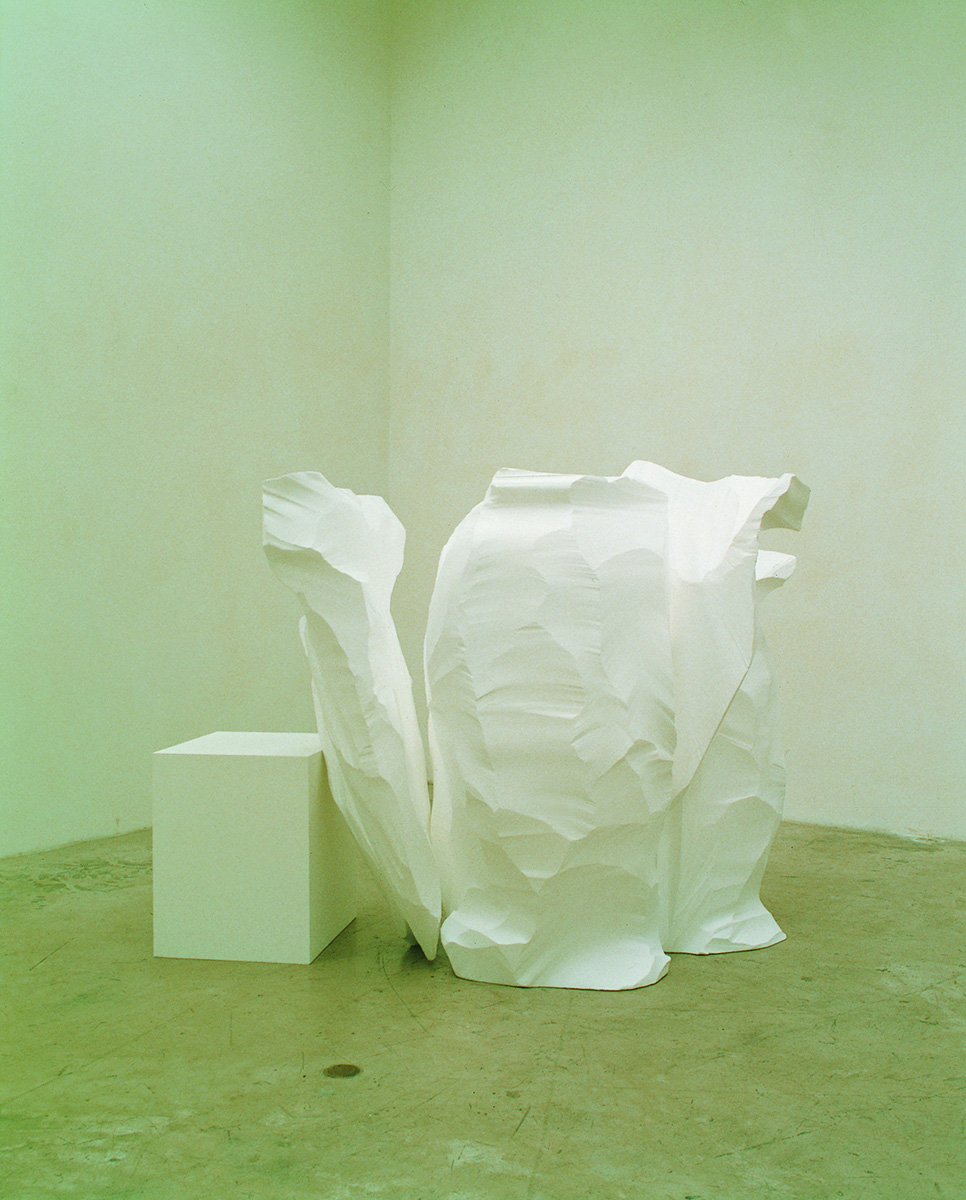

Stand in the Middle, Lie Down in the Middle, Open the Middle, Go Out, and Never

Come Back (2022) is a piece of vegan leather folded on the floor. Like the

bone for the brain, here we are reminded of the skin. A skin made of inorganic

material, the same manner in which intelligence can be made of artificial

matter. As a form, it is neither organic nor mechanical. It is simple, and yet,

very difficult to formally describe. Words do not stay easily with this one.

This way, the work effectively delivers a forceful blow to the minimal

aesthetics. It resembles an accident or the remains of an action, which ended

up leaving behind this material as a trace. All through her work, Chung

Seoyoung has shown an incredible understanding of the life of materials.

Industry develops and uses materials that we then consume. Then, when these

materials are used in art, they are subject to a complex and paradoxical

judgment. They express the industrial reality they originate in, but due to

this, they may be perceived as in-noble.

Chung’s

epistemology of matter finds a place and role for all the materials she

encounters. Art gains in her practice the role of being compassionate with

materials otherwise excluded from a traditional understanding of sculpture. The

culturally formed materials are given a second life when she unforms their

cultural identity to create a work. To put it another way, the industry puts

materials at work, giving them a role, an aim, a function. And Chung puts the

materials to sleep. Like this piece – Stand in the

Middle, Lie Down in the Middle, Open the Middle, Go Out, and Never Come

Back – she allows it to just stand, lie, open the

center of the space for us, and disappear.

In such a way, her new works seem to contrast human intellectuality against

disappearance. It is as if the “weightiness” of earlier works that are very present in the exhibition is now

entering a new phase. Through the interaction between the condensed display

of What I Saw Today and its fluid spatial layout, we understand even

better this transition towards lightness and ease that liquidate the more

restrictive mechanisms of the conscious present in the earlier works. Indeed,

trying to control the real, and the materials that conform to it or the

determinative behaviors of certain practices, is not the aim of Chung’s work. But certainly, the work wants us to gain a sensibility to

observe and be aware of the processes that nourish our everyday lives, and

eventually – with training and time – achieve an almost unconscious ability, which could allow us to

co-exist with all that surrounds us.

What I Saw Today is therefore not a retrospective of Chung Seoyoung’s practice. It is an incredible opportunity to actualize all the

exhibited works at once and create a present moment –

an eternal today – for all the works and us. This today

needs to be taken very seriously as it cannot be swallowed by a “past,” any nostalgic impulse to think of the

decades behind or an escapist mood that sends the pieces into a near future. We

need to stay in the present. Facing the work this way, it transmits an

understanding of the multiple times they contain, and further gains a

transcendent energy. Within this community of works in the exhibition, we learn

to distinguish between observable and unobservable phenomena, as well as acquire

an epistemic bearing of observational evidence both in life and art. At once,

these two realms become intertwined. And so, through her work, we become more

capable of interpreting the world around us.

Chus

Martínez is currently the head of the Institute Art Gender Nature at the FHNW

Academy of Art and Design, Basel, where she also runs the lnstitute’s exhibition space Der Tank. Previously Martínez was the Chief

Curator at El Museo del Barrio, New York, and MACBA, Barcelona, and Head of

Department at dOCUMENTA (13). Recent publications are Like This. Natural

Intelligence As Seen by Art (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022); The Wild Book

of Inventions (Sternberg Press, 2020), Corona Tales. Let Life Happen

to You (Lenz, 2021).

- This

is a famous quote by poet Paul Celan (1920–1970).

- Elaine

Scany, The Body in Pain (New York: Oxford University Press,

1985).

- Gaston

Bachelard, La dialectique de la durée (Paris: Boivin et

Compagnie éditeurs, 1936); Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time, and Everyday

Life (London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint of Bloomsbury

Publishing Pic, 2004).

- I put

“know” in italics because it is a relative “knowing.” Objects do not have a mind, but many theories have been

developing in the last decades addressing consciousness as not only a

neuronal process, panpsychism, for example. It is not relevant here to go

into detail and yet it is important to note that a significant aspect of Chung Seoyoung’s work is to subtly make us reflect on the complex dynamics,

which define our interaction with matter and things in the world. Dynamics that defy commonsensical ideas of time and perception

moving away from evolutionary biology and coming closer to quantum

physics.

- Diva

Amon, panel discussion “Promoting

and Protecting a Healthy Ocean,” in person, Our

Ocean 2019, Oslo, 2019.

- Carl

Sagan, Broca’s Brain:

Reflections on the Romance of Science (New York: Random House, 1979),

14.