Chung

Seoyoung has always introduced herself as a sculptor, but the language required

to read her sculptures is far from those prescribed to modernist works of art.

It is the language of “objects,” above all else. Pedestals have been removed. The abstract form – considered thus far to represent the spirit of the subject – was replaced by relatively familiar objects, but these hardly

generated a storytelling that exceeded their own existence. When Chung started

to work as an artist during the mid-1990s, art biennales, among other indices

of globalization, began to be imported into the South Korean art world.

Interest in different forms of media also increased; these were given such

titles as installation and media art, whereas the realism of the 1980s had reached

its exhaustion point and become subject to the historicist demand to reinvent

the workings of politics in art.

In the midst of these transformations, on the

other hand, Chung’s objects remained silent. As

globally-minded curators traveled across regions to mobilize artworks for

historical retrospection, Chung’s objects refused to

create a single narrative that dramatized her temporal and spatial biography.

Even as artists lusting for the global network started to tinker with the image

as a symbol of lightness and fluidity – at the expense

of the object’s fixity – Chung’s sculptures continued to occupy space with their characteristic

obstinacy. It was impossible to attribute a specific territory to her objects,

but more so to inscribe the concurrent program of deterritorialization in

contemporary art.

The difficulty of assigning a territory is one explanation of the lack of

discursive engagement with Chung Seoyoung’s works in

the context of the post-1990s South Korean art. It is undeniable that Chung’s acumen has inspired her colleagues, curators, and artists of the

following generations alike. Familiar thematics like “history” and “identity,”

however, failed to find space in her works, nor did she let her works spiral

down the capitalist vortex. Her silence gave rise to misapprehensions:

particularly in the face of the imperatives for “meaning” and “narrative”

typical in contemporary art, her works were understood as submitting to a

certain kind of autonomy while also betraying the autonomy of modernist

sculpture. In curator Kim Hyunjin’s words, her works “do not subordinate objects to the meaning of words but instead

return to the objects themselves.”2

Upon considering how Chung’s objects do not extend themselves onto the worldly realm of

contextualization, one could interpret that their linguistic meanings close

down to the objects themselves. Yet this interpretation is not equivalent to

recovering the overlooked or suppressed sovereignty of objects. If art has

perpetrated the violence of trapping objects at the polar opposite of the human’s meaning-making status, Chung’s objects

hardly subvert. It is true that meanings in her objects refuse to be fixed, but

such refusal does not necessarily lead to the deconstruction or subversion of

the system of meanings. As a consequence, bodies that engage with Chung’s sculpture do not belong to the sphere of pure phenomenological

experiences untainted by language. Objects cannot stay forever under the aegis

of meanings, but that does not mean that they never manifest in our

consciousness as an idea. Chung always treated objects as if she were seeing

them for the first time; she also called the objects “something

[she] encounters one day.” At the same time, she deemed

the objects a space “to inscribe values subconsciously

yet inevitably,” that is, to “project.” This project was of course not a political one that restores the

sovereignty of things, but neither did she take things as a space to manifest

the unconscious. Rather, it implied a “tension of

thought” to the extent that she herself called the

process “antinomic.”³

Consisting of objects that were closed off to the objects themselves, Chung

Seoyoung’s sculptures also aroused critics’ desire to place them among various art historical terms. One

instance is to consider her works as “consciously

distancing from the art’s social turn,” that her project is that of “gazing back at

modernism” or “existing within

the language of modernist sculpture.”³ As such, even though it was apparent that Chung’s sculpture belonged to neither pure autonomy nor its exterior, some

did stand for the former. Others attempted to push the language of autonomy

further by claiming that her work does not simply “exist

within the sculptural language” but walks outside only

to trudge back. Curator Kim Jang Un writes,

“[Chung

Seoyoung] constantly reverts back to sculpture” by “deconstructing the historical weight of sculpture and reducing it to

an object, but it is then presented with the grammar of sculpture.”4 Whether it stays within the language of sculpture or goes

outside via the object and returns, Chung’s sculpture was considered to operate as an insurmountable “specter,” or that which pulls back the

objects’ attempts at transcendence to the point of

origin.

However, what Chung Seoyoung’s objects wanted to reject

was the “illusion” or the “virtual” which modernist sculptures

attempted to generate. As her sculptures straddled tight binaries between

silence and articulation of meanings, and even as they floated a strand of

ideas between those binaries, her objects allowed no other meanings than their

functions. One of her works, Lookout (1999), is an observatory just enough to

allow an outward gaze; Gatehouse (2000) is a security guard’s desk just enough to allow a certain surveilling gaze at the

viewer. Park Chan-kyong calls her objects “functionally

identical”: “what [Chung’s works] imitate is not the objects themselves but their functions,

or their proximity with bodies, both of which could be said to lie at the core

of all objects. Carpets and linoleum are nothing more than flooring; the

lookout does nothing but observe; flowers only decorate.”5

It is this sheer functionality that lies behind Chung’s decisions not to use pedestals or dramatic lighting, stripping

their attendant authority. Through this process, the artist takes her sculpture

from the transcendental or symbolic back to the experiential – that is, where bodies exist, encounter, or collide here and now.

Despite existing and functioning in the present, Chung Seoyoung’s objects seem to be taking a few steps back. They are definitely

not heading to modernist sculpture’s place of illusion,

but there nevertheless seems to be one more layer of sensibility between

spectator and object, something that exceeds the proximity with bodies. Chung

once explained the process of making the Lookout: it all started when she held

a certain postcard. It was from a friend on vacation, and it had “a picture of a Nordic swimming pool in the 70s style” with an “image of a fingernail-sized

observatory printed at one corner.” Her sculpture, in

this case, was in the middle of the process of pulling the miniscule observatory

into physical space.

Far from being a “lookout on a

palm” or “some far away

lookout,” it was a lookout that “creates a position of a certain physical distance from [herself].”6 Here, the “lookout on a

palm” might be what the artist encountered when holding

the postcard, which could be owned in the form of an image. The “some far away lookout” could likewise be an

image – in other words, more of an idea than a reality.

The observatory that Chung wanted after all was not the product or idea but the

“real.” As Park writes, this

urge for the real is what lies behind the artist’s

choice to produce the proximity with bodies by letting her sculpture imitate

the function of objects.

Chung’s sculpture does not merely carry out the work of

bringing images back into reality. She did not want the lookout to stay as an

image, but neither did she readily yield it as a part of reality. This twofold

hesitation might also be called the constant physical distance from herself.

Regarding her decision about the size of the observatory, she responded as

follows:

The

decision about the size of the lookout, in fact, reflects my worldview towards

this object. The most important thing is the moment, or the chance encounter

with this lookout that has flown to me from an irrelevant time and space – Northern Europe of the 70s – as a postcard.7

Here,

the artist is underscoring the importance of the moment of encounter with an

image. In other words, the desire to operate and function in reality – rather than as a product or idea – demands

an additional layer of sensibility in reading Chung’s

sculptural work. The artist attempted to overcome the lookout’s state as an image by turning it into a sculpture, yet this attempt

was via a serendipitous encounter with an image. As the artist acknowledged,

this paradox, through which the negation of image leads to the preservation of

the state of an image, could stem from its scale. The lookout is equipped with

four legs for stability in addition to a ladder to look out at the view. As

such, by imitating the object in ways that are faithful to its function, the

sculptural form brings back the promise of proximity to the subject’s body. While forming this corporeal relationship, however, Chung’s lookout pushes away the subject’s position

through scale. The scale, to elaborate, seems to be decided while hovering between

observability as a statement or question.

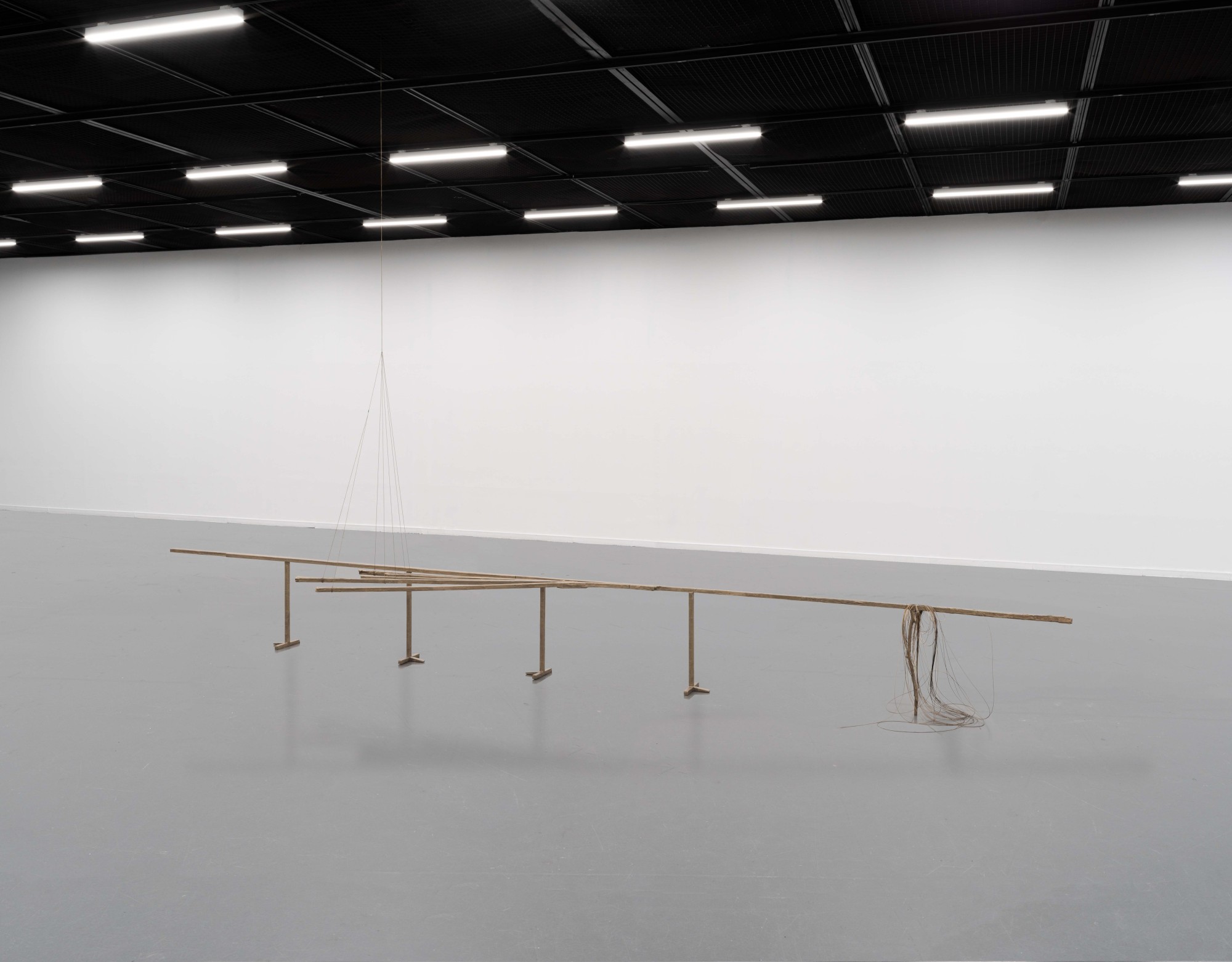

Also pertinent is the material choice. Chung’s lookout

is made with only wood; the structure’s simplicity

hinders the work from extending its meaning beyond the sheer act of looking

afar. The wooden lines, varying in width and length, do nothing but erect a

structure that observes. At the same time, it is that same simplicity that

magnifies the sensibility of minute differences slightly out of tune. The

window of the lookout, which faces the sculpture’s negative

space, is not made of wood but of glass, and the light of the surrounding space

is both refracted and inscribed on its surface. If the glass window is where

the negative space and sculpture correspond in the present, the wooden frame

absorbs light into its body and generates a difference of relative senses. This

difference in the material – and its attitude towards

light – gently pushes the observatory to face the here

and now. It further hinders the sculptural body from stepping on the ground

against gravity and pulls it back into the state of an image.

The

scale in Chung’s sculpture pulls the

object back to the state of an image, yet this scale is not just a matter

between the body and the sculpture. In the eponymous

exhibition Lookout (2000) held at Art Sonje Center, the artist placed

a single object and cleared out everything in its surroundings. The lookout

here achieves a similar level of aesthetic status to the postcard sent from a

faraway place. What is also preserved is the serendipity assumed in the chance

encounter between the viewers and the observatory in the postcard flown from

the irrelevant time and space of Northern Europe – the

lookout placed in a white cube encounters the viewers abruptly with no prior

notice. Last but not least, the lookout also stages the encounter of scales, in

which one faces the relatively tiny lookout amidst the vast landscape, similar

to that moment of coming across the fingernail-sized lookout printed on the

photo.

Images

incarnate into reality through Chung Seoyoung’s sculptures. Reality, on the other hand, hopes to revert into the

image. Her observatory marks this state of liminality –

it cannot achieve complete incarnation and precariously hovers around the state

of an image. There is a moment when her sculpture overlaps this encounter with

an image with the physical presence of the image in real time and space. This

overlap is far from being an equitable mix, or juxtaposition, of two planes of

equal status. The materialized presence threatens the state of the image and

vice versa; the two ontologies tightly confront one another with no possibility

of winning or losing. What the critics discovered in Chung’s sculpture could have precisely been this sensibility: curator Hyun

Seewon wrote that Chung’s work forms the “cross-studies that makes us confront two or more schismatic

realities”8; Park Chan-kyong also wrote on the “dialectic of the familiar and unfamiliar” in

the similar context.9

Above all, the artist herself has expressed her aversion to

anchoring her sculpture anywhere between objects and humans, let alone their

physical and universal meanings. What she underscored instead was the “imperative of their difference.”10 When speaking of the work Lookout as an example, the “universal meaning” would be the status of

the object that is thrown into reality while imitating its functions, while the

“physical meaning” would be the

object’s lonely presence in the space of reverted image

and obliterated functions, along with the resulting chance encounter between

the subject and its physical presence. It was in 1989 that the artist spoke of

the “imperative” of being

anchored nowhere. It might not be a coincidence that this was also the year

when the historical era, as it is known, announced its own end.

Having studied sculpture at Seoul National University and experienced the

stasis of modern sculptural language, Chung Seoyoung went abroad to study

sculpture in Germany. What she encountered there seems to have been closer to a

renewed awareness of the object existing in an unfamiliar space, rather than a

novel or cutting-edge methodology of contemporary sculpture. In one of her

early works entitled Berlin (1990), there lies an image that sheds

light on how, in the eyes of the artist, objects uncovered themselves while

being situated in the new world. A photocopied photograph is glued on one side

of a suitcase, with its inside filled with neatly folded white cloth. As the

work’s title insinuates, the photograph was taken by

the artist in Berlin in 1990, at the Pariser Platz in front of Brandenburg: the

historical site where the end of an era was announced in 1989.

People gathered

around the Berlin Wall, which penetrated the square and witnessed how the

bygone era, inscribed on the wall, was crumbling into pieces. And when Chung

arrived a year later, the heat of that moment had already evaporated and the

ruins of history only remained in fragments. Some made those shredded pieces of

the wall into earrings and sold them to tourists, and Chung chose to take a

photo of her friend wearing the very remnants of history-turned-ornament.

What led Chung Seoyoung to gravitate towards the object of residual history

would be the precise moment when these weighted symbols of history became

nothing but ornaments. Right when she was witnessing how the object completely

obliterated the significance of the past era inscribed within itself, the

artist pressed the shutter. Yet flattening the moment into an object with lost

meanings would not do justice to Chung’s intent. The

figure who wears an earring not only fills the right side of the image but also

has her eye cropped out. As the viewers’ gaze naturally

turns to the object, they notice another gaze coming from the left side of the

image. The former gaze rests upon the remnants outside of history, or upon the

object turned into an ornament and souvenir. Then, it faces the latter gaze of

the unknown other that arises from the interior of history. It is the gaze of

someone resting their chin on their hand. It is a gaze full of inscrutable

meanings, against all the other gazes that negate its meanings. It is the gaze

of residual history that lies opposite to the gaze of liberation.

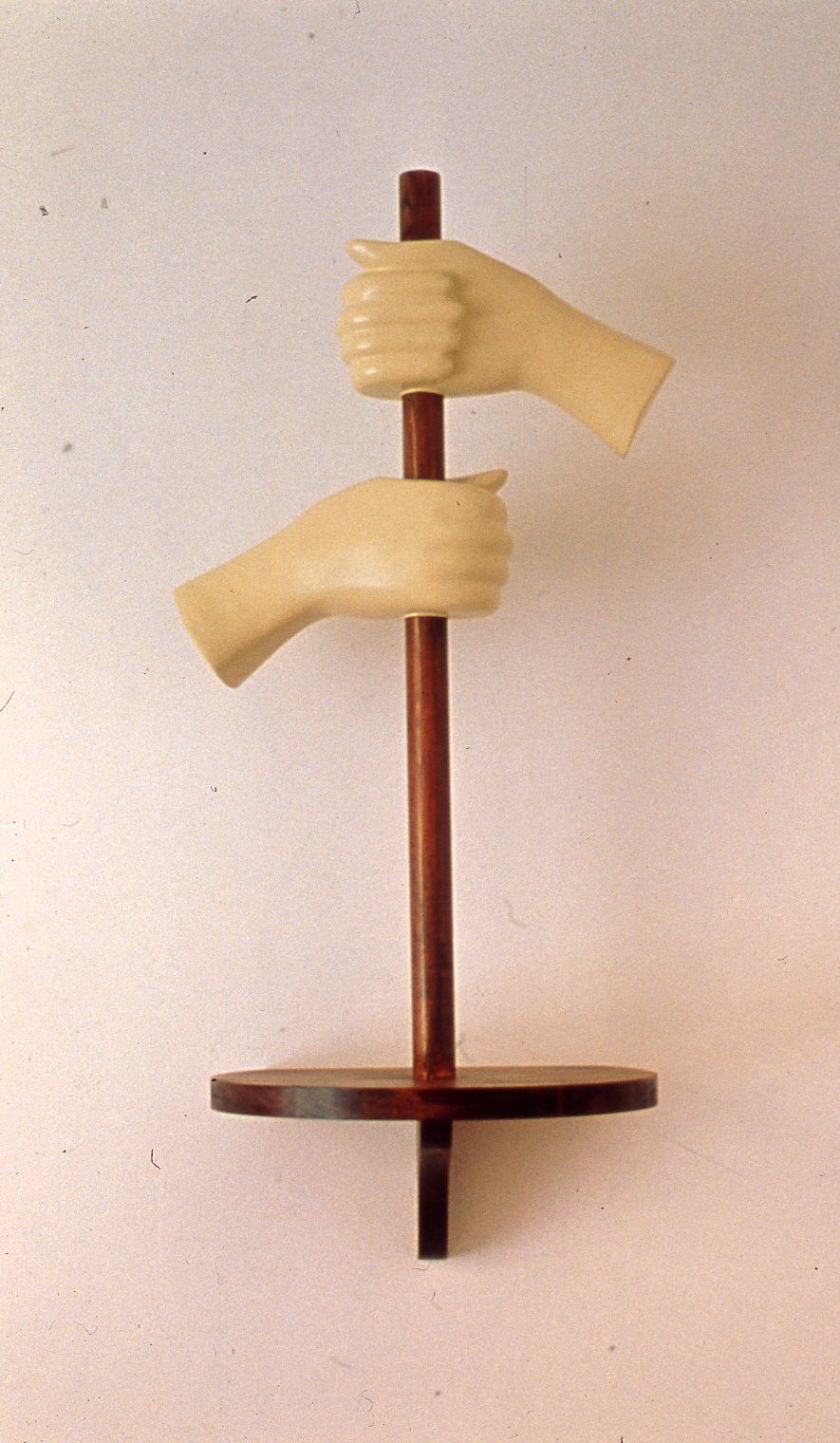

The new epistemology of objects in Chung Seoyoung’s

snapshot could be traced back to the limits of modern sculptural practice that

she faced as a sculptor. The two hands in Untitled (1994) are

separated from the body and wander in space; furthermore, despite holding a

wooden stick from both sides, the two hands create parallel forces that cancel

each other out to reach a state of inaction. Considering how the primacy of

hands has constituted a modern sculptural practice of “carnal

and spiritual carving,” the separation of hands from the

rest of the body suggests the sculptor’s own skepticism

towards the unity of the body and soul.11 This skepticism is further linked to how Chung preferred to

use words such as “task” or “labor” rather

than mind or practice.

In this sense, the fact that the image

in Berlin is an outcome of the optical unconsciousness of the camera,

rather than being mediated through hands, could be read as erasing the aura of

the body when capturing objects. Particularly considering the well-rehearsed

relationship between modernist sculpture and the subject’s mind, Chung’s sculpture could even be

considered radical: the disembodied two hands fail to generate any meaningful

incidents other than the labor of inaction – that is,

merely applying certain forces to an object. A modernist sculptor is said to

epitomize desires for “transcendence” towards the “truth of nature and universe.”12 He, in other words, attempts to unite with the mind of the

absolute. Such was the case for Kim Chong Yung who called sculpture a “conversation with the god.”13 Likewise, Choi Jong Tae’s sculpture of the Virgin Mary holds both hands together with

similar aspirations. Chung Seoyoung’s two disembodied

hands, on the other hand, articulate how her work is not directed to the

transcendental world but to the very moment when disparate forces are applied

to the object.

When located within the crevice of mind and matter, sculpture does not

represent the mind of the subject nor suggest its transcendental form. What

replaces the collapsed a priori system is the object. However, not

all objects equally caught Chung’s attention. As the

fragments of the demolished Berlin Wall attest, the objects that appealed to

the artist were ruins of history or remnants of the modern. Still, these

objects do not exist within the framework of meanings. Instead, she looks as if

she is seeing them for the first time. Earrings are worn on earlobes only

because they are earrings. Photos of souvenirs are taken at tourist

destinations because they are souvenirs. When the artist presses the shutter, objects

are nothing but functional, and historical and periodical narratives hold no

importance. As stated above, what matters is not the moment when the object’s meanings are negated but the unknown gaze that is caught

serendipitously, or that which confronts our presentist gazes at the object’s meanings, or that which appears only after the films are

developed. It is the gaze of the other, discovered a posteriori only

through the eyes of the tourist.

A

number of works by Chung Seoyoung exhibited in Germany can be read as an

attempt to translate the dynamics of gazes which intersect via the photographic

surface into the forces of objects. The plastic flower pots stacked in The

Sculpture with Rubber Band (1994), for instance, take the force between

one object and another as the sole generator of artistic form. Here, the

resulting work seems to indicate the object’s self-referentiality, yet there are still other relationships

beyond this seemingly aimless play. Using rubber bands attached to the surface

of objects, Chung turns our attention to the exterior forces that can tear down

the self-sufficient world of objects. This force exists prior to the form

created by the stack of plastic and intervenes in the objects’ equilibrium, yet remains unseen. Similar to the other gaze that is

only discovered in the negative’s transition into a

photograph, this force is only uncovered a posteriori. When Chung wrote in

an essay that “I can finally see the rubber bands; they

are seen either very well or very poorly,” the meaning

of “finally” would be closer to

this particular parallax that lies between the balance of objects and the

discovery of forces unseen.14

Chung

Seoyoung returned to South Korea from Germany in the mid-1990s. To the artist,

South Korea was a place full of intriguing objects. The world has always been

overflowing with things, but her comments that “objects fill up the world” and that she “cannot take her eyes off them” suggest that

the objects of her interest have slipped away from the symbolic world, vacated

of meanings and rushing towards the senses with their pure materiality. As with

the residues of the Berlin Wall, those objects were far from being symbols of a

bygone era but were disclosing themselves in utmost reality. Turned into

matter, they gushed into the artist’s retina with an

extremely charged reality of form, and the artist faced the brazenness of this

matter while recognizing it as a being that “brazenly

occupies the space and intrudes into [her] time.” It

was this phenomenological sense that comprised matter and form that functioned

as, according to Chung, “a kind of evidence.”15

Chung’s words could be interpreted as a statement that the object’s existence in front of her eyes was premised on the bygone presence

of a certain time – that is, the time that existed

before the object was pushed away from the past to the present. For the objects

possessing utmost reality, behind the veneer of materiality lies another

dimension of temporality that cannot be reduced into the present. Chung called

this temporality the “ghost”:

when she spoke of spending “365 days with ghosts,” she was hinting at the entanglement between the time and her

everyday life. The artist adds that this spectral being “occasionally appears in a concrete form.”16 Of course, this incarnation of the ghost that Chung

perceives in reality has nothing to do with the task of excavating the past and

reproducing memories.17

It

is not Chung Seoyoung’s job to imbue

new life into wandering souls and unfinished histories. In fact, she hardly

believes in the unity of absolute mind and matter, nor does she approve of

encounters between certain ideologies and matter. Looking back at the Korean

sculptural practice during the 1980s and seeking its alternatives, artist Ahn

Kyuchul wrote about “national memorial sculpture” as follows: “sculptors are nothing more

than slaves who obtain materials from the monarch and construct their terrestrial

Olympus.”18 For Chung, creating sculptures this way was equivalent to

extinguishing her spirit – she once

called such a sculptural practice “the dogma of the

spirit that seeks to overcome and overwhelm matter, or is bound by principles

of absolutism.”19

On the other hand, when she talks of the ghosts who

accompany her sculpture, they are not merely surreal beings found in everyday

life. Although her objects were not “materials obtained from the monarch,” Chung

was sensitive to their transformation into the illusory or surreal through

certain compositional principles. Matter in her sculpture had to live their

lives in reality. The lookout she created can only let viewers observe the

given space; it does not have to represent or reproduce the observatory as if

it is actually overlooking the DMZ. Likewise, as the carpet in her work was not

a concept but the carpet existing in real life, it had to be in the space as

such. In this context, it seems natural for Chung’s

carpet to roll itself up and spread its body on the floor, thereby transforming

the space and turning it into a locus.

As

the ghosts incarnate, Chung Seoyoung’s work no longer functions as an autonomous virtual reality or a

representation of memory on a pedestal. It is the very place where matter lives

its life, where the reality of matter materializes as itself.

In Carpet (1999), a tower erects from a reality upon which the object

rests. This erection is not due to the fact that the tower lies on the floor as

opposed to a temple. It is the very form of the tower that refuses to be

conceived and constructed in certain worldviews or styles; instead, the tower

erects as the carpet starts to live its own life. In a reality where the carpet

rolls up its own surface, reality is equal to the place and the tower. In this

process, there is no customary grammar nor secret weapon of the sculptor that

transforms the real object into a particular illusion or virtual image.

What

happens, in fact, is that the tower itself jumps out from the movement of

reality. Whether it is for commemoration, veneration, or prayer, the tower here

is an image that shies away from the reality occupied by the object. Yet it is

also important to note that the tower that rises from Chung’s carpet – or rather, the tower created by

the rising carpet – is bound to be an incomplete symbol

and a fractured image. The object, in this case, instead decides to live its

own life without allowing a chance to project and contain the transcendentalist

belief of the image imbued in the tower. In sum, the “reality” of the object here, called the carpet, incarnates the tower into

reality while simultaneously pushing it out of the state of an image into

reality. The reverse is also true.

The tower on the carpet brazenly ignores the

demand for a causal relationship; furthermore, by taking this very failure of

logic as a condition for existence, the image of the tower ends up spinning out

of reality. Let us note that although the tower rises from its own materiality

and incarnates into reality, there is no reason for the tower to be placed on

the carpet. Just like the lookout placed in a white cube, it is this unfamiliar

presence from a mismatch of time and place that the tower on the carpet

awakens. Rising abruptly from the place of reality and pushing the sculptural

state away from an object to an image, the tower evokes the tension between the

materialized presence and state of an image – all while

still choosing to incarnate in reality.

This unfolding of the sculptural form, which might be considered sensuous,

explains Chung Seoyoung’s discussion of the “moment” or “situation” rather than beauty or creation. This is a sensibility that the

artist meticulously constructs in space, while on the other hand, it is also an

awareness coming from the street. Regarding her experiences on the street, the

artist writes as follows:

Among

the signboards on the street, what catch my eyes are the square-shaped signs

with the word “flower” tightly inscribed in red. Whenever I see that sign I feel that

someone suddenly appears in front of my face, articulates the word, and then

walks away.20

The

word “flower” penetrates the

artist’s retina not as an idea but as matter that

possesses pure materiality. Locating itself far away from the rhetoric of

nature or lyricism driven by national consciousness, the word strikes our eyes

with its characteristic “reality of form” – in bold red that tightly fits around the four edges of the square.

The visuality of the image gets past our retina and into the body in the form

of waves, into the reality that clamors the word “flower” right in front of the artist’s face. Here

lies the reason the sign caught her eyes despite its modest size, much like the

observatory as small as a fingernail printed on a postcard. What has “caught the eyes” of the artist might be

small and remain in the state of an image, yet it strives to become a reality

with a force felt through the body as waves.

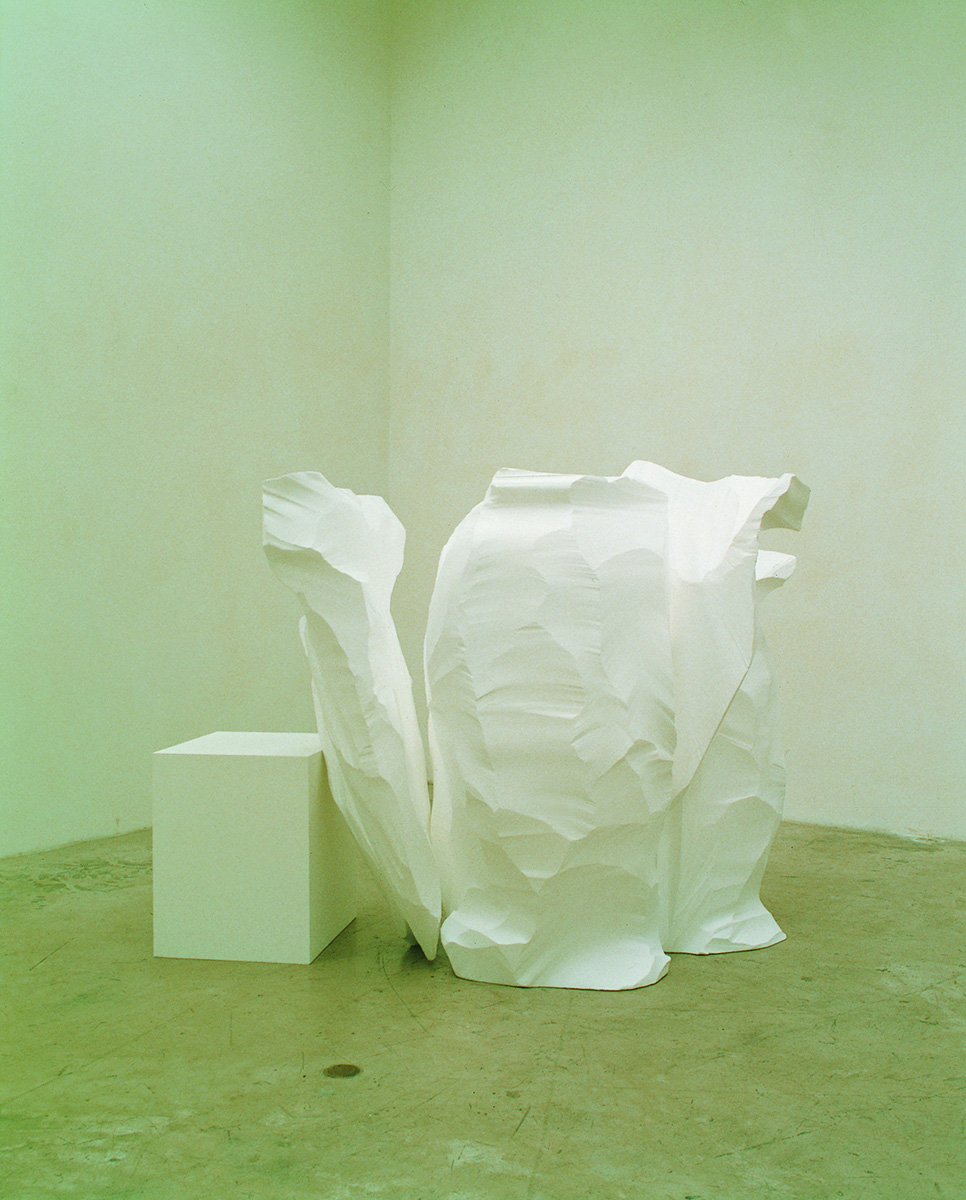

Made

mostly of Styrofoam, Flower (1999) does not sculpturally reproduce

the materiality of language encountered on the street. Chung Seoyoung takes a

block of Styrofoam as big as her body and starts carving without sculpting it

into a certain form. The fact that the physical labor solely consists of the

spur of the moment – devoid of any

transcendental interventions – is evocative of the

artist’s experience of walking down the street. The

surroundings turn opaque, and our attention converges. Just like the language

of signboards that approximates reality, the approximation of the floral form

emerges from the formless Styrofoam block. It could be said that the flower on

the signboard wants to turn itself from an image to a wave of reality.

The

Styrofoam, on the other hand, wants to become an image that sprouts the idea of

a flower from the materiality perceived by the body. Yet just as the flower

screams at our face and “walks away,” the Styrofoam does not remain in place as an image or an idea of

the flower. Notable in Flower, in fact, is the bare reality of the

Styrofoam block’s roughly exposed surface produced from

the artist’s labor. In the words of Rosalind Krauss,

the “idea of inner necessity has been removed”: in other words, “the idea that the

explanation for a particular configuration of forms or textures on the surface

of an object is to be looked for at its center.”21

As such, the necessary relationship between the image and

the surface of matter has collapsed. This is partly because the shape

resembling a flower emerged in the process of intuitive and experiential

carving. Yet this is also because there is an inexplicable logical void between

material an image, that is, between Styrofoam and flower. Despite the loss of

the center and the sudden leap of meaning, Flower is still able to

capture its ontology as an image from its relationship with Styrofoam

materiality – the artist, after all,

spoke of the flowers via the work’s title. Another

factor could also be the white wooden pedestal which, with its momentary

reliance on sculptural convention, gently pushes the industrial material into

autonomy.

Chung Seoyoung’s sculptures incarnate ghosts into

reality, but the central object of the sculpture remains silent despite the

spectral presence. These ghosts appear from time to time in the present, but

the objects just continue to live their lives. The floral form abruptly incarnates

in reality, yet the Styrofoam – once a psychic medium

that had summoned ghosts – “walks away” and continues its life as an industrial

material. Lookout exists right where there is a sculpture,

functioning as a real observatory while aspiring to return to its pre-incarnate

state as a tiny image printed on the postcard. There is a life in reality, but

there is also a life as a silent object in an image.

Such temporary incarnation

of ghosts in Chung’s sculpture means that flowers no

longer elevate the spirit of the subject as a symbol of lyricism. The image of

a flower does not constitute a modern subject through unity with nature or

formation of ethnic consciousness, but becomes a sensibility that approaches

the bodily reality through sculpture itself. It is notable that this

sensibility has more to do with the instantaneous encounter with a flash-like

image than a long-lasting afterimage, and the gaze created from such an

encounter is far from forging a modernist visuality or the gaze toward utopia.

The gaze from the lookout, for instance, operates in reality through bodily

interactions without offering any historical perspective or chance for empathy.

Then, it eventually dissipates. The lookout as an image, now silent, overlooks

the narrative and forecloses itself from the waves generated by its own.

Chung Seoyoung’s sculptures seem to straddle the border

between image and physical presence, or between ghost and reality. And it is

her text work that captures the sensibility of the sculptural object’s ontological transformation through these borders. According to the

artist, this movement is “the sum total of what

gradually becomes lumpier and what gradually becomes clearer,” resembling a “cheeky addition.” Upon looking at Chung’s sculpture, there is

a moment when the surroundings gradually blur out and our attention converges

into its image. There is also a moment when the image conversely blurs out and

the materiality of the real is felt through our bodies. The “sum total” of these two dimensions must skip

all processes of deduction and reasoning to the extent that it becomes

shameless.

In another text, Chung wrote, “Throw things

that flew from afar as hard as you can. If not, you may have to remember the

wrong things forever.” The sum of such texts should be “cheeky,” according to Chung, because if not

we might “forever remember” the

“wrong things.” If one could

say that the ghosts of modernity are only remembered in museums, those memories

are inevitably reconstructed.22 Memory in the case of Chung’s sculptures, on the other hand, consists of the very moments of the

ghosts’ incarnation like a flash of light. Just as the

ghost of modernity surfaces not from history museums nor archives but from a

postcard with a 1970s Nordic landscape, or from a tiny signboard on the street,

those memories have “flown from afar.” These could be the moments when the memories become clearer, but

she chooses not to remember them forever. Instead, she throws them “as hard as she can” in order to remember

only the flash of the moment.

In

Chung’s other work, -Awe (1996), it is this flash

of the moment that is captured by a word of hesitation – “awe” – written on traditional vinyl

linoleum. This object, which probably has not intrigued our close-looking thus

far, is just a linoleum-made imitation of the surface pattern of traditional

floor paper. This flooring material could symbolize the particular visual

culture that has penetrated into our lives during South Korea’s rapid industrialization. It could also be a subject of

sociological analysis by evoking imitation or kitsch. Yet it seems to be the

object’s pure materiality, or the utmost reality of its

form, that captures the artist’s attention.

Transferring a linoleum plate into a picture frame seems to be a shameless

presentation; at the same time, it could also be interpreted as an invitation

to the surface of reality that has been overlooked in the midst of all the

details in our lives. It was only during Chung’s era

that we could afford to contemplate on things that have supported our realities.

In other words, it was only due to the conscious distancing from our

challenging past that the modern objects could break away from ideologies and

meanings, and rush toward the retina with colorful, sloppy, yet meticulous

forms. It is this contemplative distance that -Awe generates from the audience,

relying on the age-old custom of a painting hung on the wall.

On the surface of the painting, Chung Seoyoung wrote a seemingly meaningless

exclamation: awe. This empty syllable may arise from the artist’s sudden encounter with an object; it could also be the sign of her

tentative refusal of things that cannot be said. A straight line, possibly

drawn with something similar to a ruler, prolongs a moment of delayed meanings.

At the same time, it could symbolize a few seconds of hesitation before one

utters the syllable. The absence of letters and figures in the painting

conversely preserves all possible senses and memories within the picture frame – amazement, discomfort, inutterability, or inexplicability – that we experience in reality.

The painting, in this case, becomes

an object that is at once a realistic matter and the evidence of the past. The

utterance in -Awe relies upon this aesthetic convention, imbuing certain

strength to the fleeting emotion that the syllable connotes. Its cursive font

further contrasts with the monotony of the straight line and temporarily

enables the word to represent the spirit of the subject. The object has thus

become a painting – its stiff linearity does not

reproduce or remember the past but still evokes a feeling of the indescribable

flash of encounter that sums up the long past. A painting that is not a

painting, -Awe eventually goes back and forth between the sensibility of

flash-like moments and the insignificance of the object in question. It is

because the effect of the aesthetic conventions on which the sculptor relies

might resemble a flashlight in the first place –

linoleum cannot make a good painting, just as cursive script hardly possesses

an aura apposite for our times.23 Here, the artist just chooses to throw what “flew from afar … as hard as she can.”

Like -Awe, Chung Seoyoung’s Wave (a remaining

part of the installation work Ghost, Wave, Fire, 1998–2022) has also flown from afar. As she summons waves to traditional

vinyl linoleum, they bring temporalities other than the here and now and the

real. It goes without a question that Wave does not merely reproduce waves in

the form of a sculpture. As clay mixes with oil and sways between gravity and

its own viscosity, the movement of matter becomes that of the waves. In the

eyes of the sculptor, this play of matter is itself a ritual dedicated to

another temporality. Perhaps since both movement and play overlap with the

ritual, the wave seems to arise from the linoleum floor despite coming from an

unrelated, faraway place.

As theatrical as this movement seems, however, it

also dies away. The waves in the work are closer to formless vibration than

objects – they glide on the surface of the slippery

floor, yet it is also natural to recognize them as a fixed object. They can

never construct a transcendental space on which the subject projects their mind

and emotions. Rather, they are the objects that have blocked those

possibilities from the start; they are images that already petrified the moment

of uncontrollable movement. The layers of temporalities put up by Chung

Seoyoung’s sculpture are thus indeterminably thick.

Throughout the passage of time, there is nothing that can comprise an identity

in Chung Seoyoung’s sculptural oeuvre. As the waves

arise, what flew from afar raises its head in the present, and ghosts incarnate

in reality. Yet nothing promises its eternity.

The temporality that features in

the movement of reality is nothing more than a flash of the moment. There are waves

that approximate reality, and at times there are images that make sudden

appearances in the present, but both revert back to a movement that dies out.

Like temporary and repetitive ripples on a serene waterfront, the ghost

engraves its face on the surface of reality only to sink back in. When Chung

brought up the phrase “what I saw today” in the title of the exhibition rather than “yesterday” or “back

then,” that is because her sculptures refuse to

reproduce sceneries of the past. To Chung, using sculpture to carve out a place

for bygone sceneries is only to embellish the past. It is also to flatten the

depths of the past as a simple sign. There is nothing more oppressive to the

artist than being eternally fixated on a certain sculptural system or grammar,

in addition to taking sculpture as a means to enshrine and elevate such

systems. Instead, Chung chooses to merely see – the day

before yesterday, and again yesterday, and then again today. “Today” for her is not a place where the past

is reduced to a readily retrievable sign of the permanent present. It is,

instead, a place where things once seen in the past reveal themselves again

today.

In this context, what constitutes the field of sculpture in A

Wanderer (2022) is the motion of cement. Just as soft clay brought waves

into reality, cement fails to fix its shape permanently, revealing its own

liquid-like properties. Furthermore, its matter guides our gaze to the surface

of the present where our bodies and sculpture meet. Beneath the rough and dull

surface emerges a shape resembling a stone statue of an animal. We might be

more familiar with a stone statue with a solid and even surface, but what

actually unravels in front of our eyes is a creature that is precariously

holding on to its form in its relationship with matter. Here, we are speaking

of cement as comprising an unstable combination between matter and form, but it

is important to note that cement has been regarded as a material that has

constructed our modernity with its particular solidity.

Stomping on the

pre-modern, cement erected a city by turning itself into concrete roads and

building blocks. In Chung’s sculpture, on the other

hand, this material features a statuesque form that could only be seen at sites

like a palace or tomb. The relationship between the stone statue and cement

thus goes beyond the coincidence or leap and reaches the paradox: the very

material that has erased the mythical worldview from our consciousness is,

conversely, unfolding the world of myth in front of our eyes. The statuesque

form in A Wanderer pushes this cement floor –

that which would have been seen yesterday, and day before yesterday, and today – away from the crevice of an unpolished city or the site of an

unfinished construction and onto a pedestal. Nevertheless, while this chain of

ideas momentarily provokes our attention, it soon dies out as we encounter the

actual surface of the matter. The square space that the sculptor has sharply

dug out between the stone statue and pedestal pushes each form back into its place.

Subsequently, the pre-modern sensibility of the modulated matter immediately

transitions into the undried materiality of cement. Rather than being a

pedestal that props up pre-modern time, it could be said that the place created

by the cement heads toward the unfinished modernity left in the present. Matter

can be perceived as something else when situated in the chain of ideas, but it

also vaporizes this very chain of ideas at a formidable speed. This is probably

because the statuesque object appears in reality through the denial of its

existence in the first place. The modern sense of applying cement engraves the

pre-modern time connoted by stone statues in the sculptural form, while also

erasing it. As the title implies, the form in the sculpture is a wanderer who

meanders the contemporary, modern, and pre-modern, and these three layers of

time unveil themselves as the artist applies the cement.

The

everyday objects in Chung Seoyoung’s works include not only a cement base and stone statues but also

inconspicuous objects that have filled up our surroundings for a considerable

period of time. There are objects that uncover concealed time and feature it in

the present, but there are also objects that have always been there in silence.

The chair in A Good Moment (2022) is one such object. An object that

we definitely have seen somewhere, while not special enough to remind us of

that particular moment of seeing, is pulled into the sculptural field and

exists in front of our eyes. It would be erroneous to call this object a stool

or chair; like a classical sculpture that unites with the pedestal and isolates

itself from the secular world, this everyday object is gently pushed away into

the autonomous sphere.

A yellowish color envelops the pedestal along with the

object in ways that evoke customary sculptural grammar, but it is difficult to

conclude that the object has turned into a sculpture. On the one hand, the

difficulty lies in the scale of the object: being life-sized, it still demands

a familiar relationship with the users’ bodies. But

above all, the difficulty is that the pedestal and object are in the

ontological relationship of being both together and separate at the same time.

The smoothness of the monotone pushes the pedestal and object away from the

secular and toward the sculptural, while the pedestal also does not support the

object but separates it. The four holes dug between the legs of the chair and

the pedestal preserve the sense of the everyday life of objects. The hidden

part of the chair leg, on the other hand, pushes the object away into a

slightly autonomous state, but then the black rim contrasts itself with the

overall yellow and brings the four legs together, bringing the chair back to

reality. Despite this formal juggling, the main reason that Chung’s sculpture can push the chair from everyday life into a sculptural

state lies in the physical presence of pieces of wood.

Placed on top of the

chair and attracting atmospheric light on its surface, the wood is devoid of

use value and is not an object that abides by intentions and regulations in

order to generate an idea. The square piece of wood, therefore, is just a

good-enough object to boast its physical, everyday-like presence in the

otherwise sculptural field. However, the wooden block does not merely perform

artistic autonomy using different relative senses. What it also performs is

everyday life, like the task of stacking well-trimmed wooden blocks one after

another without losing overall balance. The outcome of this performative act is

not the tampered chair that has turned into a sculpture through the pedestal,

but the familiar chair of reality on which the object is placed. Nevertheless,

the stack of wooden blocks cannot reduce the chair into a state of a daily

object. This is because the act of building each unit one by one intentionally

slides out the customs or systems that constitute the sculptural form.

The

object that sits on the chair, therefore, stays in a self-referential state – that is, the thing itself – rather than

being another piece of sculpture on the pedestal. In the end, the wood blocks

perform self-sufficiency through repetitive stacking, and the chair cannot

extend beyond its physical support and thus remains within its prescribed

artistic form.

In the midst of various performative events that occur around the chair, ideas

are suppressed while only traces of movement remain. What unfolds in front of

us in Chung’s sculptures are such moments of minor

adjustments. The “sculptural moment” that she proposes is a state in which only the rhythm between the

sculptural state and everyday existence remains. At the very moment when the

units that make up the sculpture vibrate between one reality and another,

without being fixed in their place, what is left on the other side is a

snapshot photo of flowers. In Barthesian terms, photography is an illogical

combination between layers of time that were “there

then” but not “here and now,” and I perceive Chung’s photograph of the

flowers as making another wave in this ontological commotion.

But that moment

will not last long: although the flowers do not exist here and now,

accompanying it is an envelope that blends with the surface of this silent

photograph. When the brown light reflected on the envelope’s surface corresponds to the color of the wooden block, our eyes can

rest on the surface of the objects, on the planes where one color meets

another. For a sculptor, wouldn’t that be nothing but “a good moment”?

Jihan

Jang is an art critic based in Seoul. He graduated from Korea National

University of Arts, Department of Art Theory, and is currently a doctoral

candidate at the Department of Art History, Binghamton University. He received

the 2019 SeMA-Hana Critic Award. His publications include That, There,

Then: The Writings and Drawings of Kim Beom and Chung Seoyoung (Seoul

Museum of Art, Mediabus, 2021).

- Chung

Seoyoung often used the expression “sculptural moments” in describing her

work.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “Samuleui

gadamgwa tusa’e euihan jogakjakpum jejakyeongu” (A Study on the Production of Sculptures through Participation

in and Projection of Objects), MA diss., Seoul National University

Graduate School (1989), 26-27.

- Ujeok, Ujeok,

no. 2-1 (2007), 33.

- Kim

Jang Un, “Chung

Seoyoung:Yuryeongwa deobureo” (Chung Seoyoung:

Along with Ghosts), in Chung Seoyoung: Gonggireul

dudeuryeoseo (Chung Seoyoung: Knocking Air) (Seoul: Barakat

Contemporary, 2021), 49.

- Park

Chan-kyong, “Jeonmangdae:

Chung Seoyoung’ui samul”

(Lookout: Chung Seoyoung’s Object) (Seoul: Art

Sonje Center, 2000), 4.

- Ju

Hye-jin and Chung Seoyoung, “Bulanhan jijeomeurobuteou umjigineun geosi soljikhangeot” (Honest Things Are What Moves from the Site of Anxiety), Kyunghyang Article (May 2014), 29.

- Ibid.

- Hyun

Seewon, “Jeonsi’ui sigan: Chung Seoyoung” (Exhibition

Time: Chung Seoyoung), in Chung Seoyoung: Knocking Air, 103.

- Park,

“Lookout: Chung

Seoyoung’s Object,”

4.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “Neul

gongireul bakkugoshipda” (I Always Want to Change

the Air), in Chung Seoyoung Jogakjeon (Chung Seoyoung’s Sculpture Exhibition), exh. cat. (Seoul: Han Gallery, 1989),

n.p.

- Choi

Jong Tae, “Gak,

bugak, geurigo chimmnuk” (Sculpture,

Non-Sculpture, and Silence), in Hyeongtaereul chajaseo: areumdaum’ui balgyeon geurigo changjoreul wihan girok (In Search of Form: Discovery of Beauty and Notes for Creation) (Paju: Yeolhwadang,

1990), 31. Choi also advised Chung Seoyoung’s MA

dissertation at the Department of Sculpture, Seoul National University

Graduate School.

- Choi

Jong Tae, “Jeoldaereul

hyanghan tamgu” (The Study towards the Absolute),

in In Search of Form, 148.

- Choi

Jong Tae, “Chimmuk’ui salm, georukan seongsang” (The Life

of Silence, Holy Icons), in In Search of Form, 162.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “GHOST WILL

BE BETTER,” Hyeondaemunhak, vol.530 (February

1999), n.p.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “Ms. C’ui Chung Seoyoung inteobyu” (An

Interview with Chung Seoyoung by Ms. C), in The Speed of the Large,

the Small, and the Wide, 151.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “GHOST WILL

BE BETTER,” n.p.

- For

instance, Park Chan-kyong finds the mannequins in the War Memorial of

Korea surreal. Although he takes a critical view at how every corner of

the War Memorial is inseparable from a certain political agenda, he still

senses that “the ghosts

of war have been reincarnated into a body.” What

Park suggests is that the concrete realism of representing the war had

flowed from the past to the present and subsequently gained physicality.

To quote his words again, “the long-term prisoner

called the Cold War has gained a new life as a mannequin in the War

Memorial.” See Park Chan-kyong, “Gukbangchohyeonsilju’ui: Bangmulgwan” (Defense Surrealism: The Museum), in Beullaekbakseu:

Naengjeon emoji’ui gieok (Blackbox: The

Memory of Cold War Images) (1997), 149.

- Ahn

Kyuchul, “80nyeondae Hangukjogak’ui daeaneul chajaseo” (In Search of the

Alternatives of the 80s Korean Sculpture,”

in Minjungmisureul hyanghayeo (Towards Minjung Art)

(Gwahakgwasasang, 1990), 149.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “Samuleui

gadamgwa tusa’e euihan jogakjakpum jejakyeongu,” 24.

- Chung

Seoyoung, “Dareunkkot

du gae” (Two Different

Flowers), Hyeondaemunhak, vol.532 (April 1999), n.p.

- Rosalind

E. Krauss, “The Double

Negative: a new syntax for sculpture,” Passages

in Modern Sculpture (New York: The Viking Press, 1977), 250.

- In “Defense Surrealism: The Museum,” 28,

Park Chan-kyong writes as follows: “Commemoration – that is, the reconstruction of memory – involves not only the interests, customs, and status of the

remembering individual but also the political agenda or preferred culture

of the remembering group. Although they may be diverse, the motives

involved in the case of the War Memorial could largely be called patriotic

war pathos.”

- Chung

Seoyoung once said as follows: ‘‘The ‘awe’ in

cursive itself is an imitation. I was not that skilled at calligraphy, so

all I did was to ‘imitate’

the calligraphic script.” See Hong Sun-myeong, “Cheoljeohamgwa heosulham’ui gongjon” (The Coexistence of Meticulousness and

Sloppiness), Weolganmisul (November 1999), 70.