The following excerpt from the

artist's statement on Park Wunggyu's website offers a key to understanding his

broader practice:

"I am always highly

responsive to things like 'impurity, impure situations, impure emotions.' And I

accept the process of resolving them as a form of play. During this process, I

am often reminded of religion. For example, I associate the shape of a dead

insect’s body with dazzling Buddhist paintings, and clusters of moths stuck to

my window with the packed iconography of a cathedral. I believe that

envisioning the most sacred image from something most base is itself

religious—and also impure. In recent years, I have primarily focused on

insects. But in my work, the specific subject is not of great importance.

Whether it is an insect or a sacred icon, they are no longer separate for me.

What matters more is the attitude with which I look at it, and how I distinguish

it. Thus, the forms revealed in my work are closer to dummies serving similar

functions."

This statement introduces a core

conceptual keyword essential for understanding Park Wunggyu's work:

"negation" (bujung, ‘부정’ in Korean).

The term "bujung" in Korean carries multiple meanings. First, it

refers to "negation" in the logical sense—as in denying the existence

or validity of something (e.g., "He denied her statement"). Second,

"bujung" can also mean "injustice" or

"impropriety" in a normative sense (e.g., "There was an act of

injustice during the college entrance exam" or "A politician’s unjust

accumulation of wealth"). Third, and in ritual or religious contexts,

"bujung" (written as 不淨 in Chinese

characters) can mean something "impure," something that defiles or

violates sanctity—a taboo object (e.g., "impure things" or

"being tainted by impurity").

Though these meanings are

distinct in their Chinese character forms, they often intermingle in everyday

usage. Take, for instance, the phrase, "He is a negative person." Is

this implying that he constantly denies things? That he behaves improperly? Or

that he desecrates what should be sacred? Possibly, all these connotations are

implied. Even in English, the word "negative" or

"negativity" reflects this kind of ambiguity.

What interests me is that Park Wunggyu

himself appears to embrace this polysemy of "negation" as central to

his practice. Consider the phrase from his statement: "I am always highly

responsive to things like 'impurity, impure situations, impure emotions.'"

Here, the term “impurity” resonates simultaneously with injustice (不正), impurity in the ritualistic sense (不淨),

and logical negation (否定). Later, when he says, "I

believe that envisioning the most sacred image from something most base is

itself religious—and also impure," the implication of "impurity"

clearly leans towards the sacred/taboo dichotomy of 不淨.

In his artist’s statement on the

series, he writes: "The ‘Dummy’ series begins with image collection.

Starting with everyday encounters, I save all images of 'negativity' that I

come across on my smartphone into a photo album." The Korean word

translated here as "negativity" is again ‘bujungham’ (부정함), which defies reduction to a single meaning among injustice,

impurity, or denial. Interestingly, the translated phrase "images of

'negativity'" captures this ambiguity well.

Further, Park writes:

"Religious iconography involves certain recurring schemas. The way figures

are arranged within a frame, the decorative motifs, or symbols related to

repetitive numbers—these function as methods of capturing the negative objects

that become sources for my work. They are also a form of self-discipline that

allows me to control how I approach the impure." In this context, the

"negative objects" (bujungham-ui daesangdeul) and "impure

things" (‘bujunghan geot’) are translated respectively as "objects of

negativity" and "injustice" in English, again underscoring the

multiplicity embedded in his use of the term.

All this suggests that when Park

speaks of "negation" (bujung), he is intentionally invoking its full

spectrum—impurity, injustice, and ontological denial. It is a deliberate

conflation that animates his work.

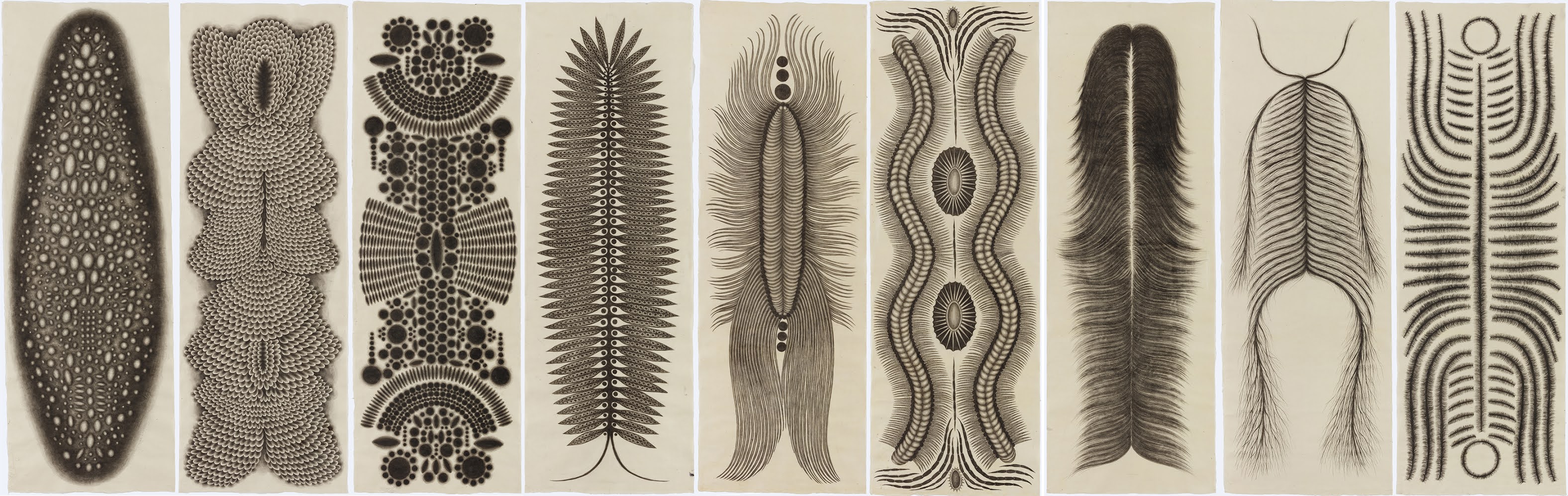

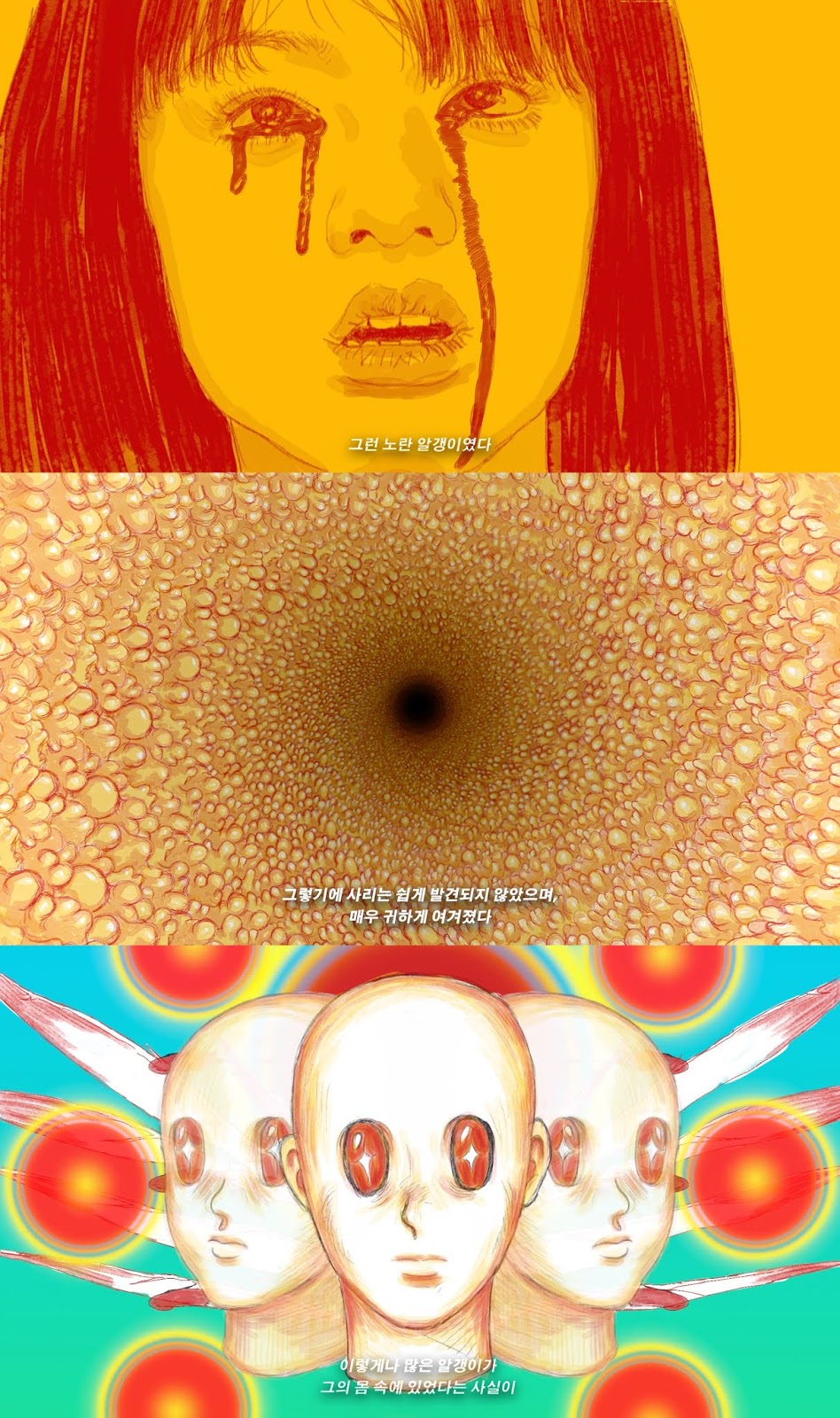

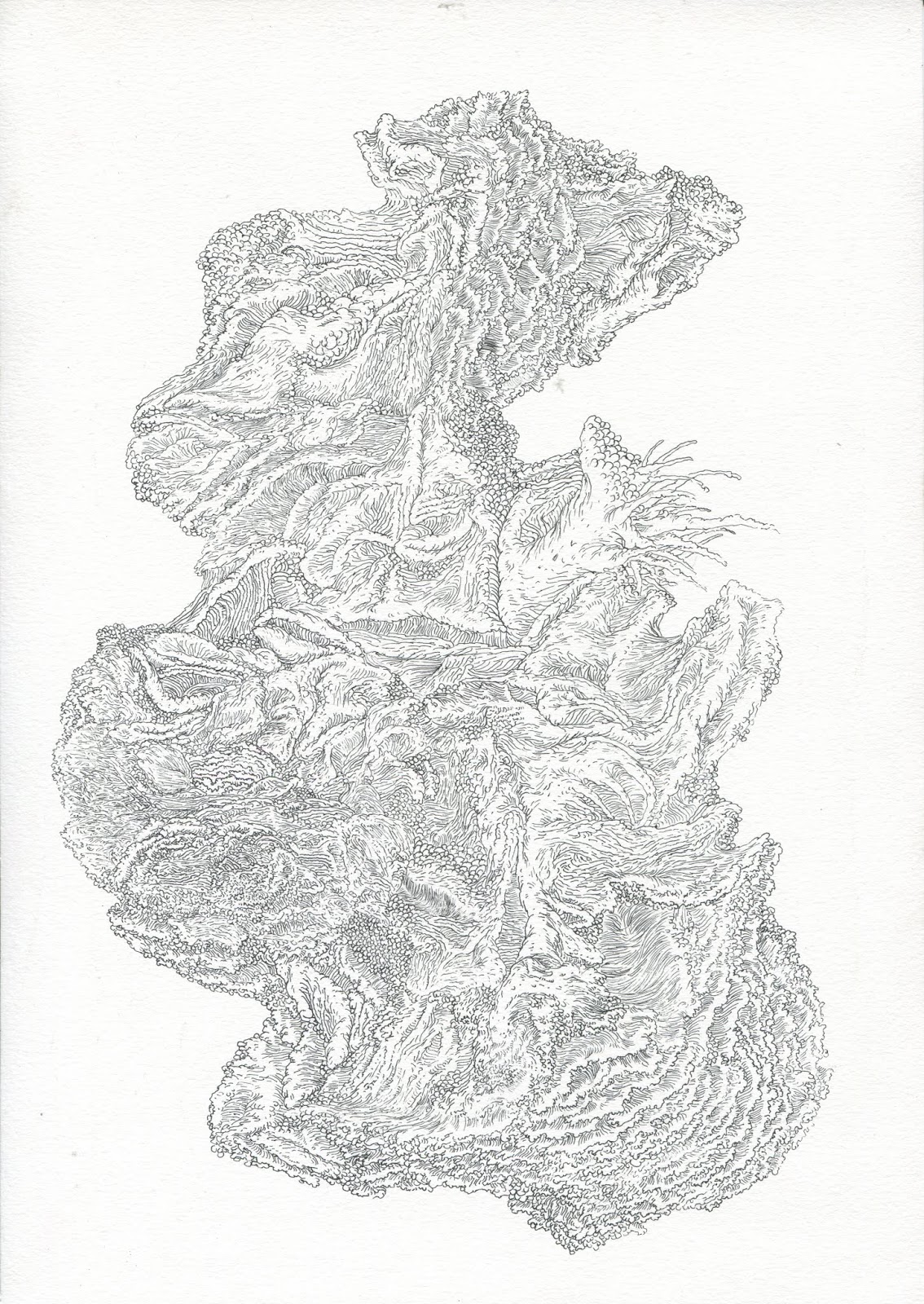

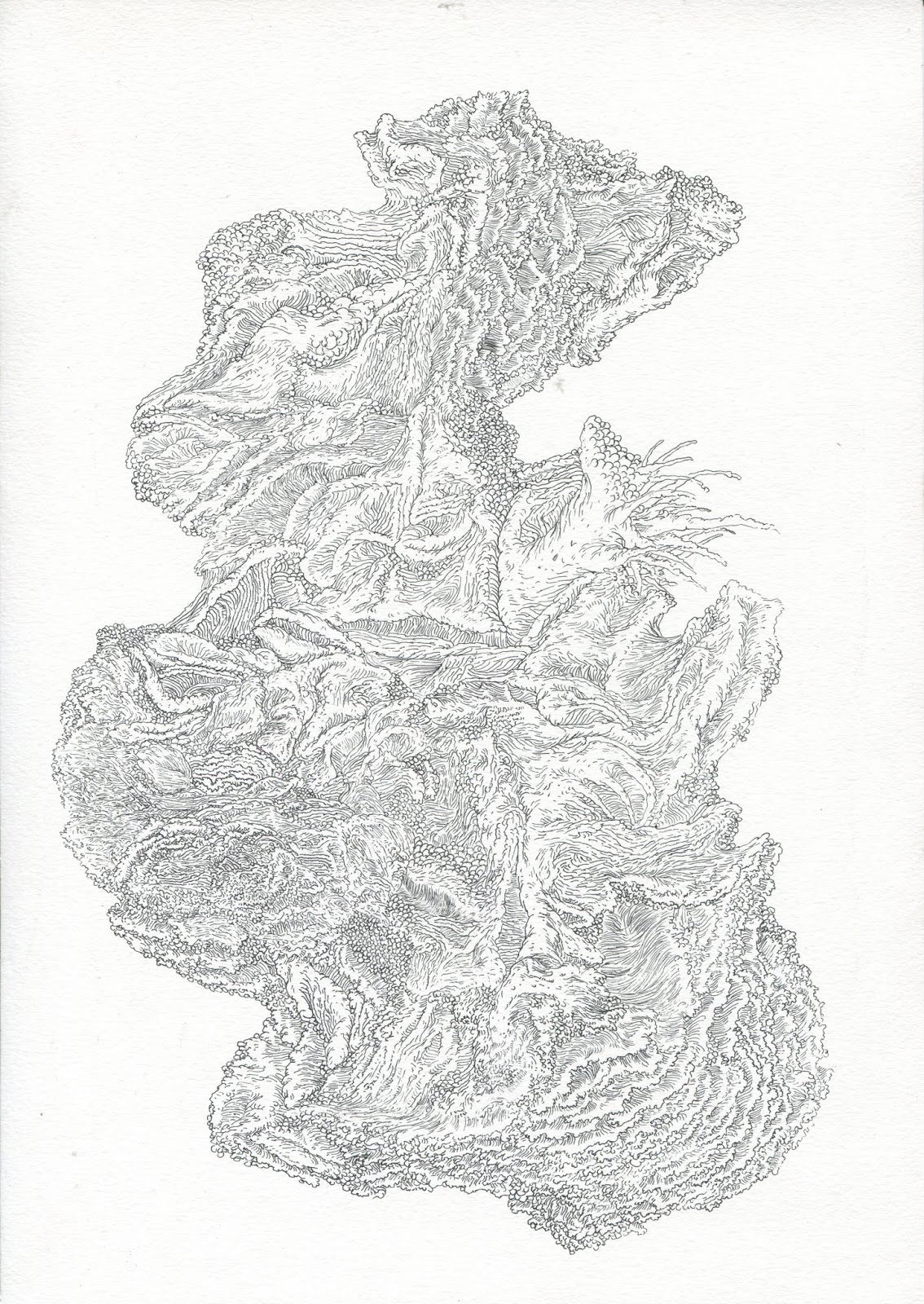

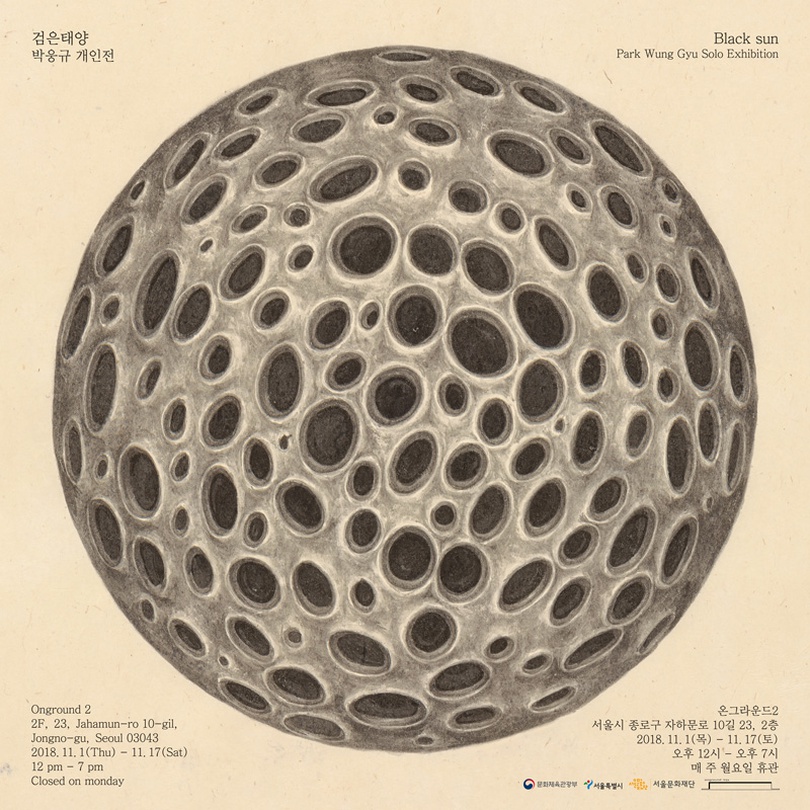

In 2012, in his early career

works such as the ‘Sputum Drawing’ series and Sputum Crystal,

Park Wunggyu strongly emphasized the meaning of “impurity” (不淨) among the many interpretations of “negativity” (부정). By transforming substances expelled from the human body—such as

phlegm and tonsil stones—into visual forms resembling sacred paintings or

Buddhist relics (sari), the artist connected what is “impure” or “dirty” to the

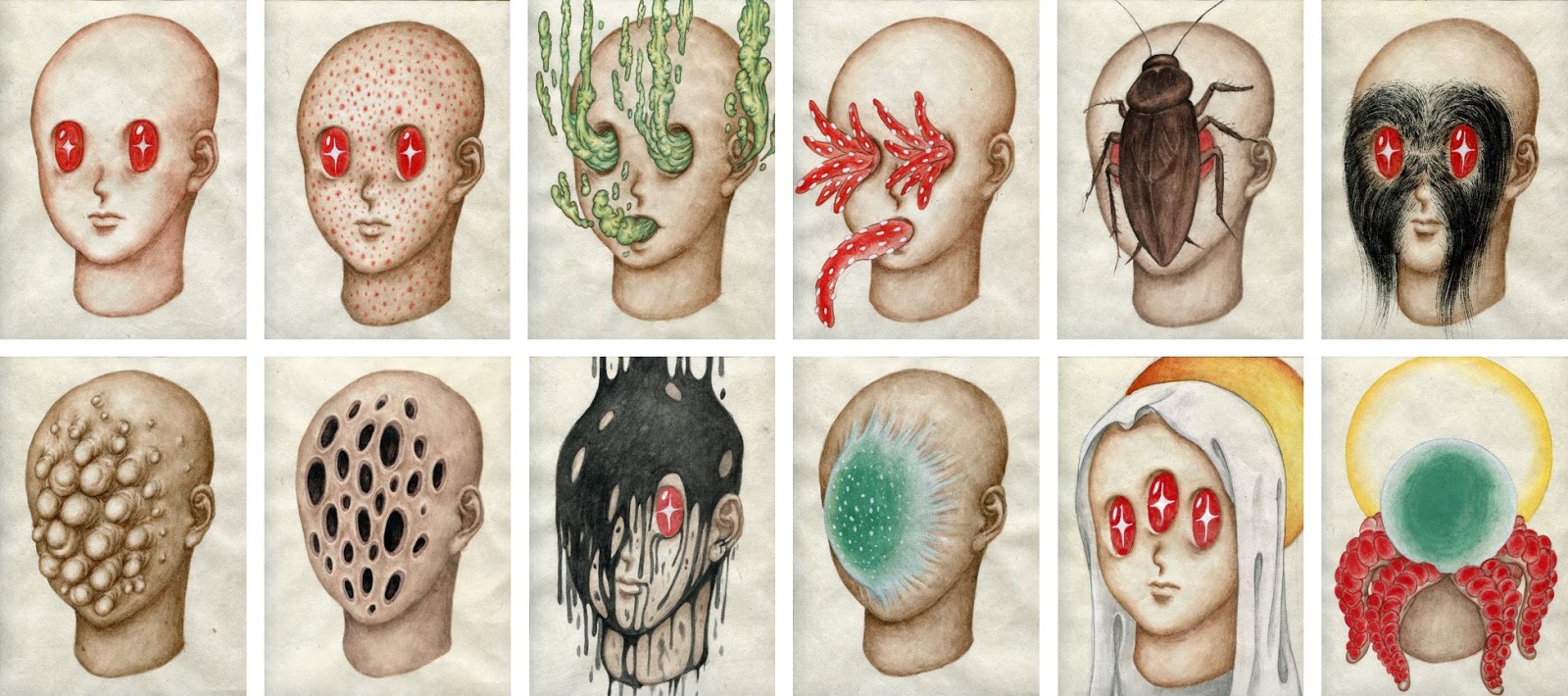

domain of the sacred. In his “Dummy” series, which emerged after 2015 and played

a crucial role in establishing what might be called Park’s signature style, a

different meaning of “negativity” takes center stage. These uniquely patterned

“Dummy” paintings appear at times like insects or bugs, at other times like

plants photographed by Blossfeldt, or even like microscopic organisms seen

under a lens—or they might resemble icons of the Madonna or Christ. Unlike the Sputum

Drawing or Sputum Crystal series, the depicted

subjects in these works are not themselves “impure” (不淨)

by nature. Regarding these works, the artist states:

“I try to read the code of

‘negativity’ within certain objects when I see them. If they meet that

condition, I save them to my photo archive. During the work process, I refer to

these images directly or indirectly. They are not reproduced as-is in my work.

These images are often interbred, mutated, and sometimes become entirely

different forms in the process. What’s important is that I adopt the form of

religious iconography to implement these images.

”

What does it mean to “read the

code of negativity” not only in repulsive insects or bugs, but also in everyday

objects, plants, or even religious icons? I interpret the term “negativity”

here as “negation” (否定)—the refusal

to affirm the being or validity of something. Whether the subject is a

repulsive bug, a beautiful flower, or a sacred icon, what Park does is refuse

to affirm the aura assigned to each—those emotional and normative frameworks

that have become so internalized that they feel natural. The repulsiveness of

bugs, the beauty of plants, or the sanctity of icons is not something

inherently embedded in the objects themselves. These are composites, born out

of a complex mixture of emotions, values, and norms that we have developed

through our relationship with these objects. In this sense, we might refer to

them as possessing a certain "aura."

To “read the code of negativity”

in these objects is to reject those auras—to refrain from being swayed by them

and instead to confront them from a different perspective. And because of this,

these objects can be “interbred,” “mutated,” or transformed into “entirely

different forms” by the artist. In this practice of negation (否定), religious iconographic form plays an essential role. As the

artist points out, religious iconography often represents objects through

“repeating schemata”—that is, through patterning.

As is well known, patterning is

one of the most essential survival mechanisms for living beings. Unless an

organism is able to detect some form of pattern within the chaos of its

surroundings, it will be overwhelmed and unable to survive. Patterning is the

abstracting capacity to group various individual details into coherent

categories. A lion on the hunt cannot afford to give equal attention to every

blade of grass, pebble, or shadow—if it did, it would never catch the rabbit

hidden in the brush. It must be able to abstract all the countless parts that

make up a rabbit—ears, legs, fur—into a singular concept: “rabbit.” Without

this abstraction, hunting would be impossible.

To pattern something is to

understand and order the world in a way that is meaningful for oneself. Through

this, living beings replace the vague dread and anxiety caused by the infinite

chaos of reality with a sense of how to respond and adapt. Humans are no

different. If we were unable to abstract and pattern the overwhelming detail of

the things around us, we would be incapable of taking any action. In Wunggyu

Park’s “Dummy” series, the “method of negation” (否定) operates in precisely this way.

This is why, following the ‘Dummy’

series, Park could say: “In my work, the physical subject itself is not that

important. Whether it’s a bug or a sacred image, these two are no longer

separate to me. What matters more is the attitude with which I regard them, and

the way I distinguish between them.” The focus here is this act of “negation” (否定)—refusing the inherited aura, patterns, or accepted meanings of

objects, and instead patterning them anew through the artist’s own conceptual

framework. This is the ethical and aesthetic force that underlies Park’s

distinctive visual language.

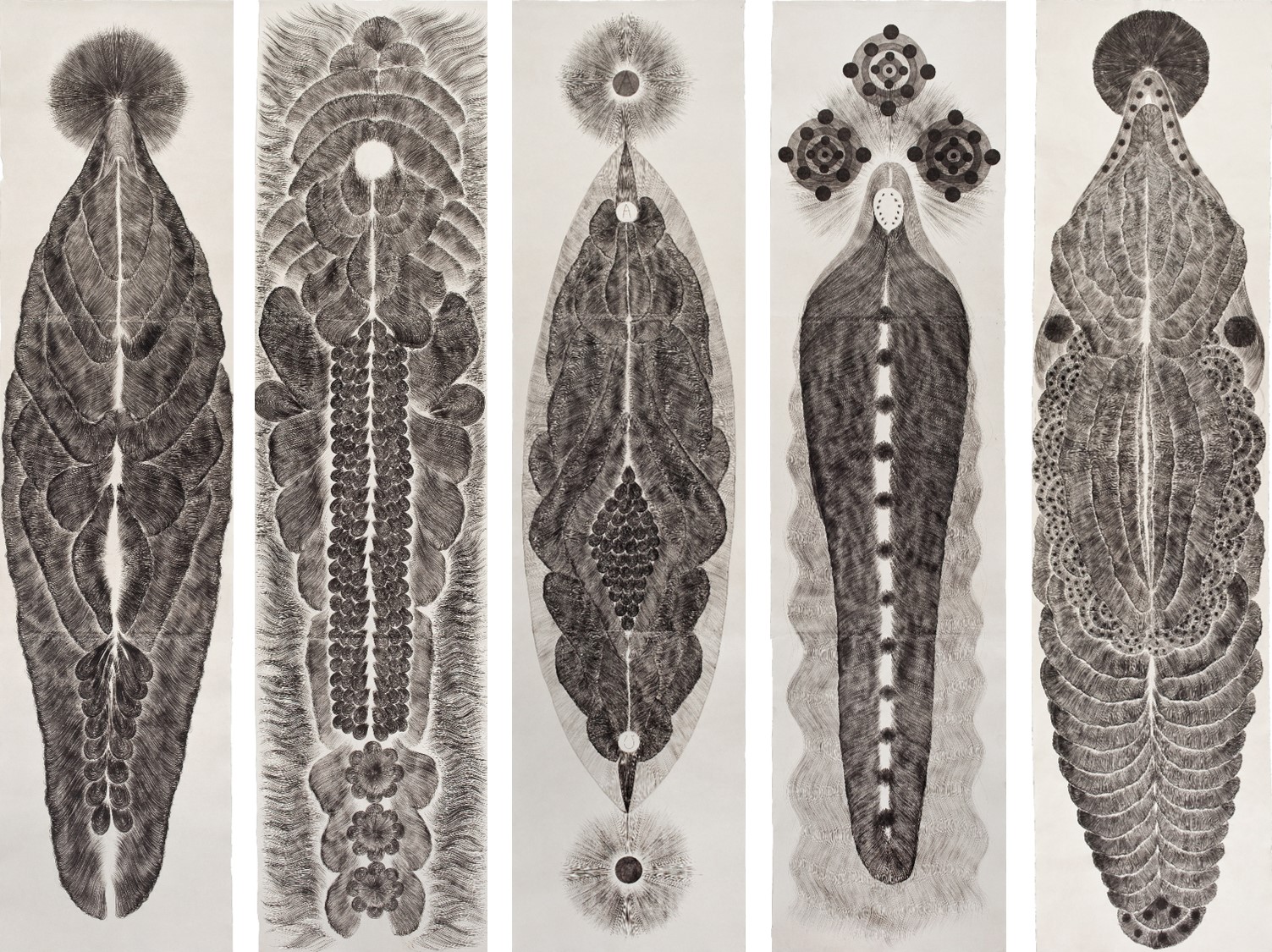

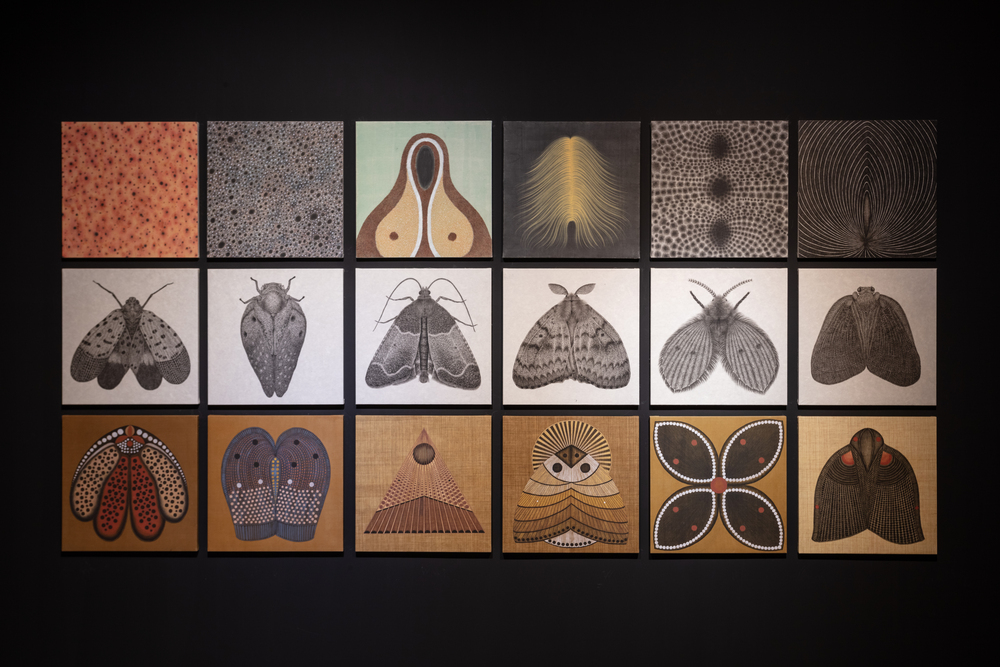

The work Eighteen Moths,

presented before the Saengsaenghwahwa exhibition, is where Wunggyu Park’s

methodology of “negation” (否定) is most

explicitly revealed. Eighteen Moths is composed of a total

of 18 works, grouped into six sets, with each set containing three pieces.

Within a set, the three works differ in form, color, and material. Based on the

installation at Danwon Art Museum, the lowest pieces are painted with pigment

on hemp, the middle ones are rendered in ink on paper, and the topmost works

are painted with pigment on paper. According to the artist, these three types

of paintings represent “three ways of depicting the insects that appear in my

studio.” He describes these methods as “observing closely (neutral), trying to

understand their form and structure (positive), and attempting to feel their

texture (negative).” These three categories are drawn from Buddhist doctrine.

In Buddhism, the 108 earthly desires originate from the three kinds of

sensations—good (好), bad (惡),

and neutral (平)—that arise when our senses (eyes, nose,

tongue, ears, skin) come into contact with external stimuli such as color,

scent, taste, and touch.

Park appropriates these

categories through the concepts of affirmation, negation, and neutrality, and

applies them as modes of depiction: “observing closely (neutral), trying to

understand form and structure (positive), and attempting to feel texture (negative).”

On this basis, Eighteen Moths generates a multitude of aesthetic questions that

ripple outward like ink dropped in water. If we “attempt to feel the texture”

of something we dislike, might that dislike be “negated”? Could the act of

observing something closely render it “neither likable nor dislikable”? If we

try to understand the form and structure of a thing, does that mean what we

once called “good” ceases to be good?

In Buddhist practice, the goal is

to reach a state of equanimity—one no longer swayed by good or bad sensations.

If one were to attain such equanimity, how might the moths clinging to one’s

window at dusk appear? These are the types of questions that arise while

viewing the 18 paintings on the wall. Park, in this way, seems to resemble an

image filter embedded within the vast image-circulation network of our time. He

filters out all the unjust (不正) and impure (不淨) images drifting through the network by negating (否定) them and transforming them into captivating new images. In doing

so, he strives to maintain a state of equanimity as an image filter himself.

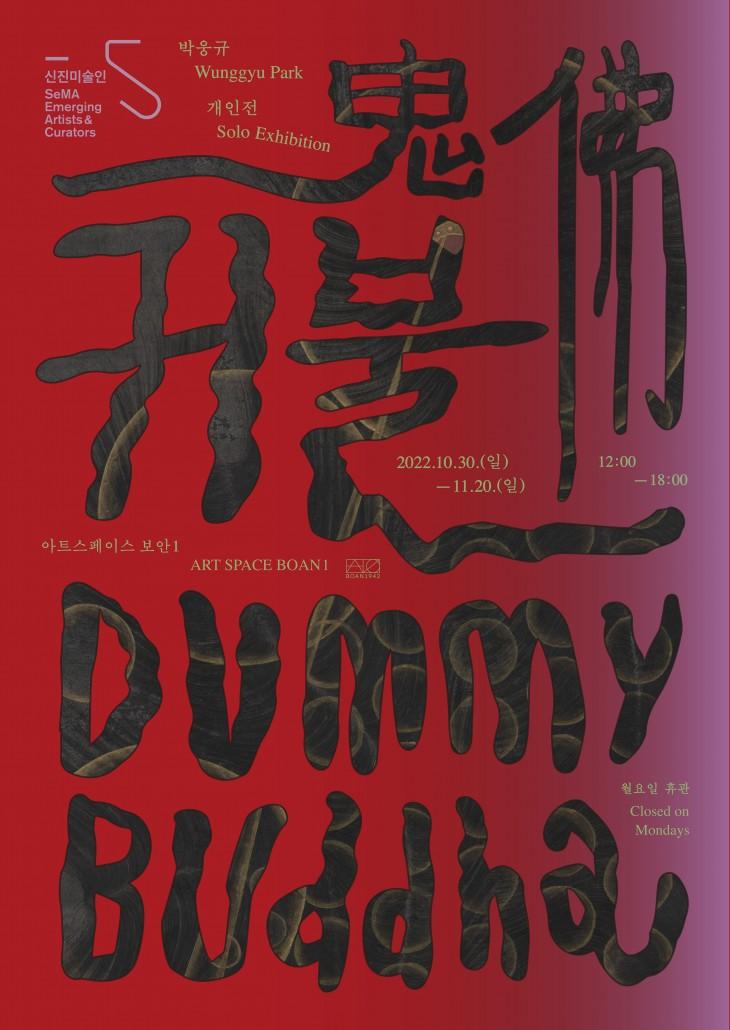

In the Danwon Art Museum

installation, Sisters—a painting on aged hemp depicting

“Kali,” the goddess said to bring misfortune with her grotesque appearance—was

gazing meditatively at two red paintings titled Scar, hung

on the wall across from it. The scars, etched onto her skin and rendering her

appearance grotesque, are met with an attitude of calm acceptance. Perhaps this

is the artist’s model for the image filter of negation: a state of composure in

which one faces the grotesque traces on their own body without judgment.