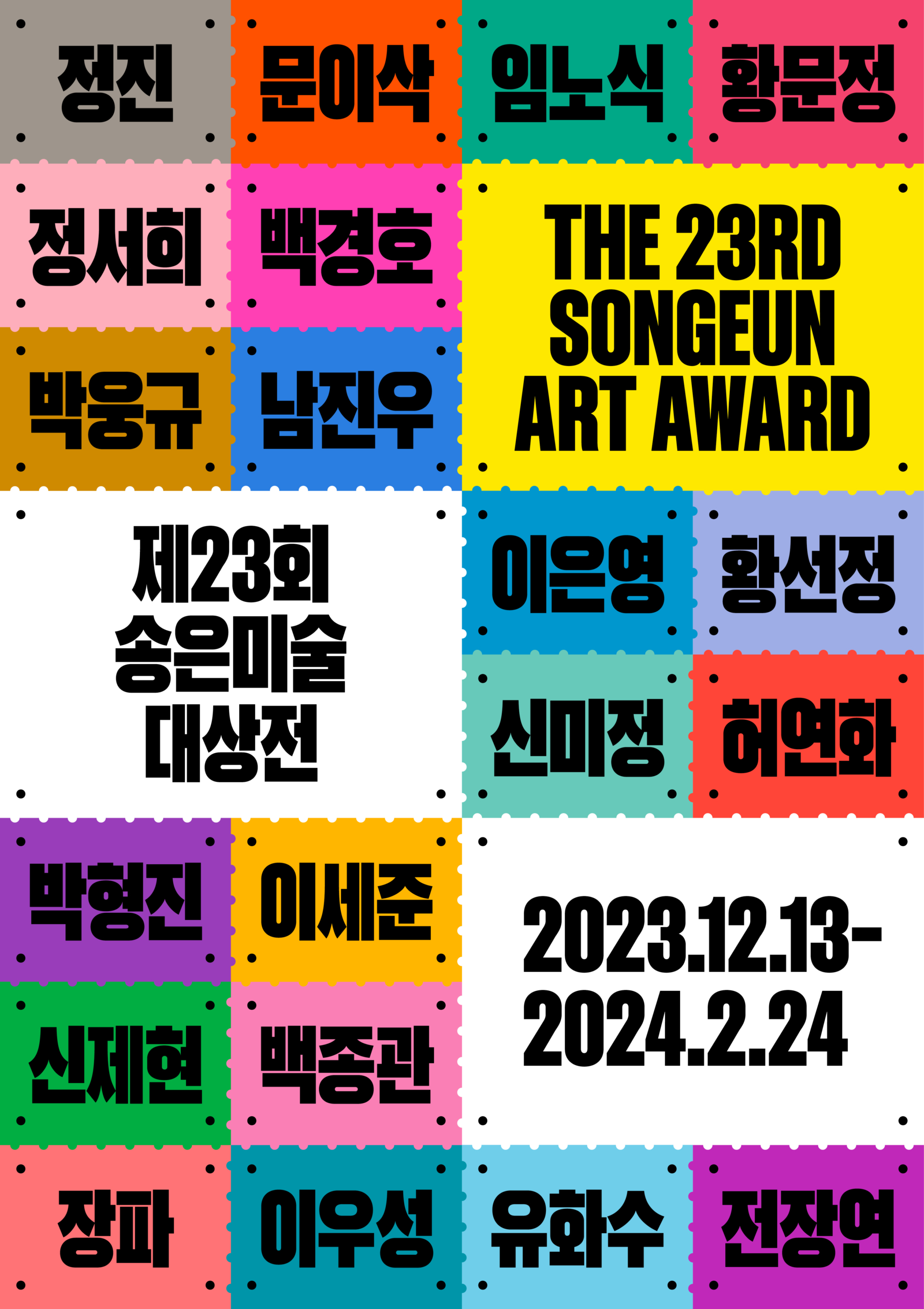

Impure sacred

When I first encountered the works of Park Wunggyu, I prematurely

dismissed them, thinking, “This just isn’t for me—it’s not within my realm of

interest.” They felt overly religious, yet blasphemous; too explicit, yet

obscure. My habitual tendency to categorize things—me versus you, sameness

versus difference—was fully at play. Simply put, I was caught in a web of bias

and preconception. So I reminded myself to wait. Artists and their works must

be experienced directly; it’s in that encounter that unexpected stories emerge

from the collision of spatial and temporal coordinates.

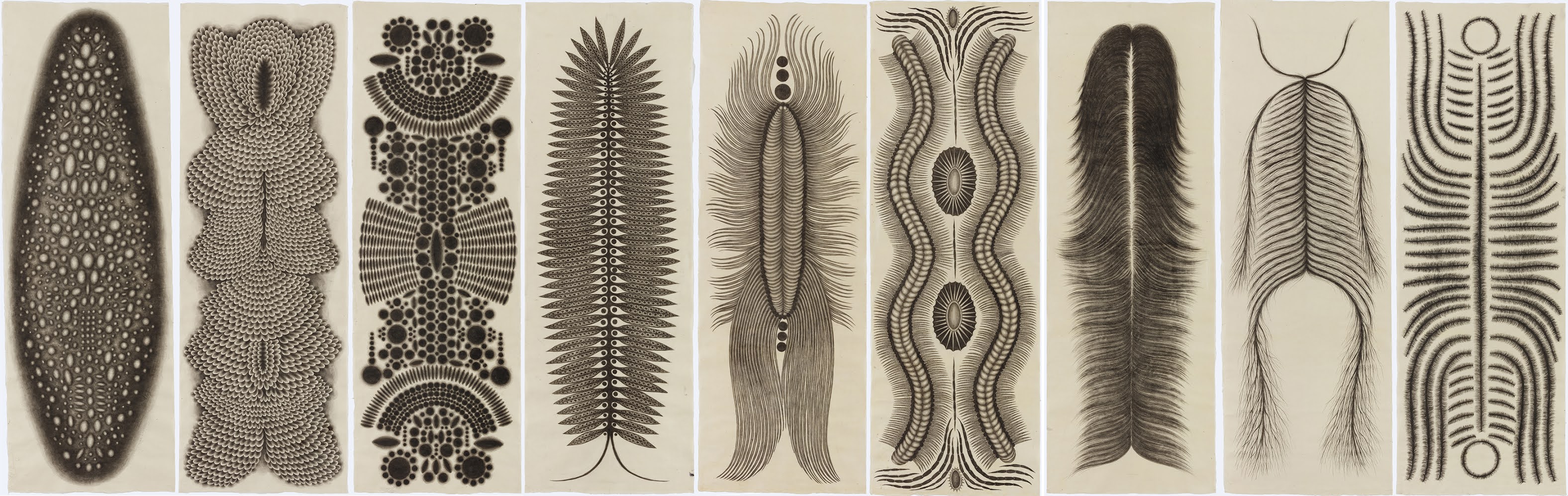

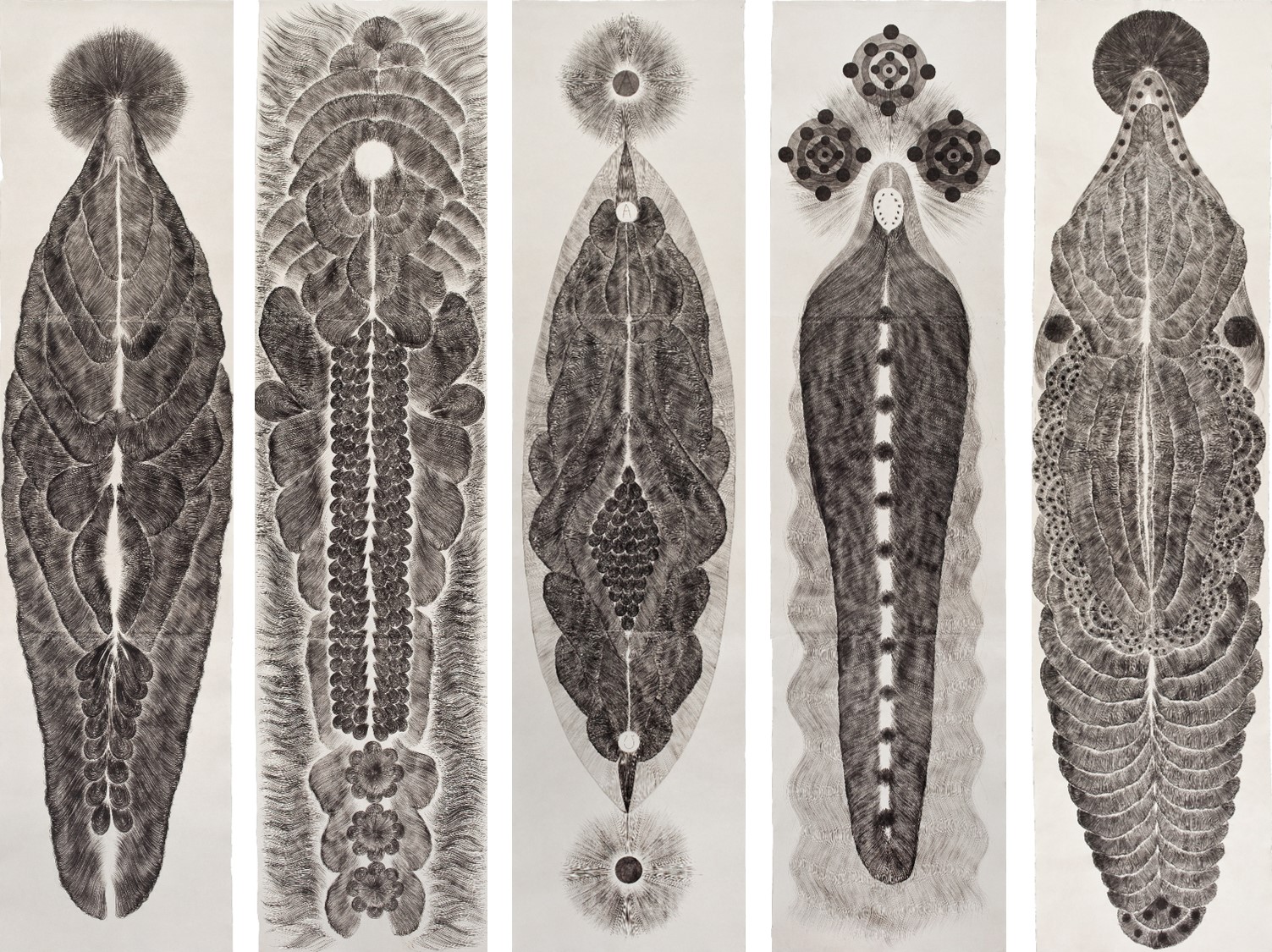

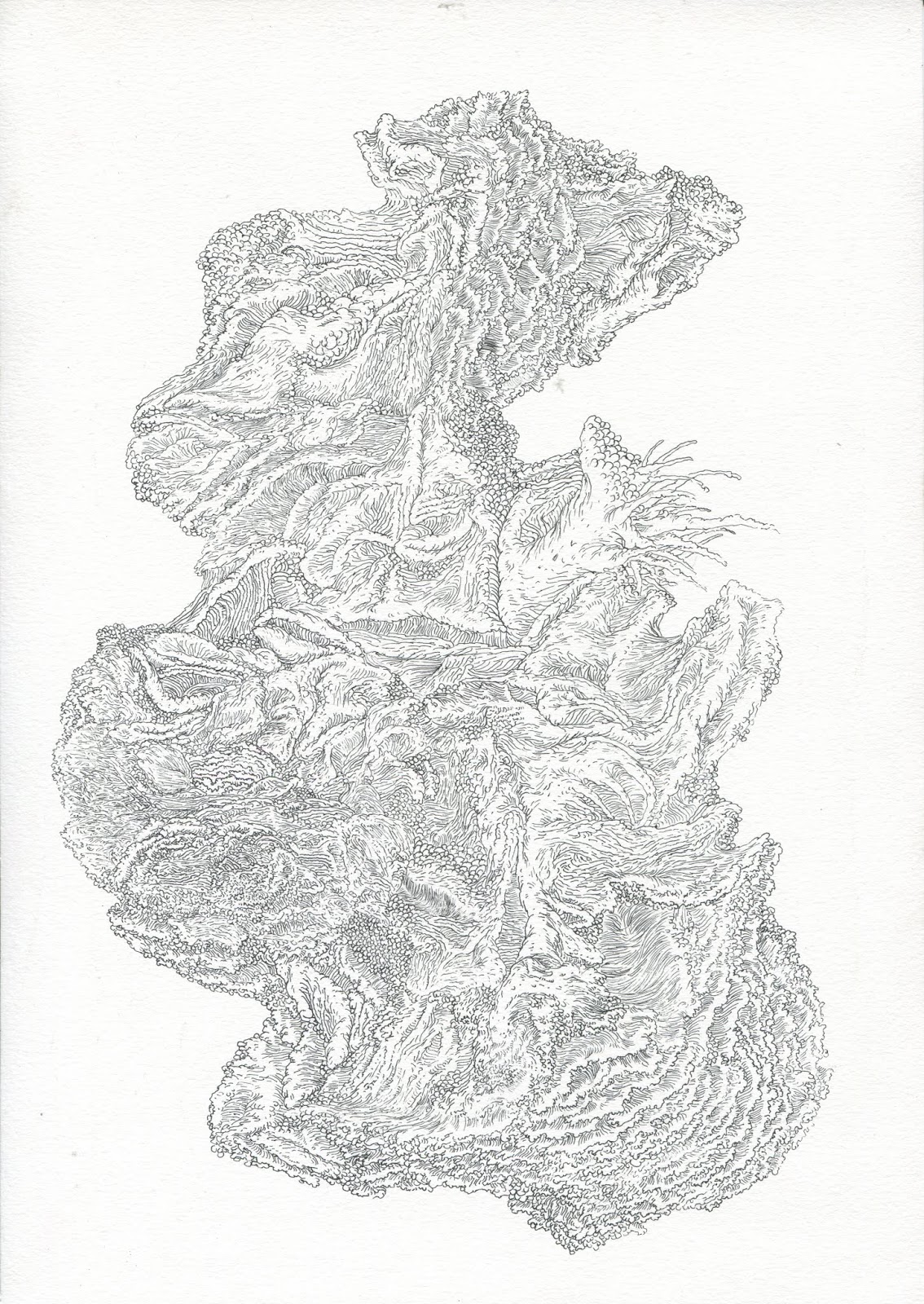

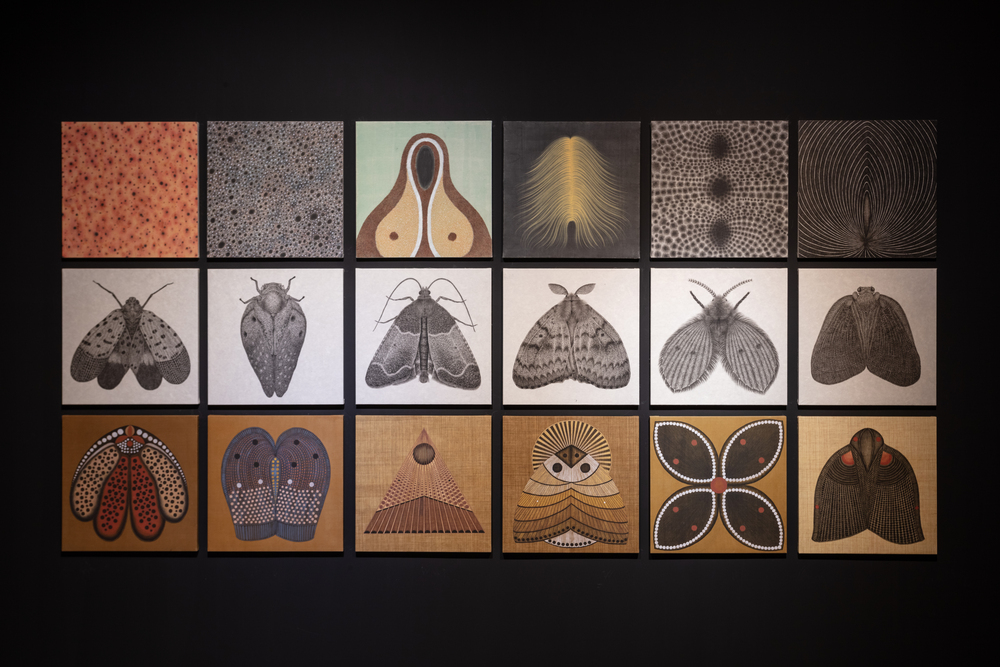

To roughly summarize Park’s ongoing interests: religious relics

and iconography, sexual organs and phlegm, and animated faces. Seemingly

disjointed, yet somehow connected. A sacred relic appears like a sexual organ;

a Catholic icon resembles a shamanic talisman. Phlegm, a bodily secretion, is

expelled like a sacred Buddhist sarira. The cartoonish faces—genderless,

monstrous, alien—morph into unknown beings, sometimes biological, sometimes

not. His work is simple yet complex, filthy yet sacred. Figurative yet

abstract, Western in form yet deeply rooted in East Asian traditions—both ink

painting and colored illustration. Who would paint something as vile as phlegm

with such care? Why are holy relics and sexual imagery brought into such

intimate proximity? These are the kinds of questions his work elicits. It

unsettles the mind.

But meeting the artist in person turned out to be a complete

reversal. With a pale face, short-cropped hair, and a long, cape-like coat, he

spoke softly—almost like an ascetic monk. It was hard to imagine that such

sacrilegious, grotesque, and provocative work came from someone so gentle.

Listening to him and reading his artist notes, I realized there was something

that possessed him: religion. Since childhood, he had been surrounded by

Catholic relics and iconography at home. For him, the images of Jesus and Mary

were not only steeped in sorrow and tragedy but were also mass-produced,

grotesque, kitschy objects. He wanted to escape the rituals and customs that

oppressed him. He wanted to resist. And yet, this religious atmosphere lingered

and was reborn in his work.

Another major fixation was the body—particularly the sexual

organs, long deemed taboo and unspeakable. Shockingly, those sacred relics

often resembled genitals, appearing hermaphroditic or even depicting

intercourse. Strangely, it didn’t feel real. It felt like something surreal,

ancient, alien yet familiar. Both biological and artificial, both natural and

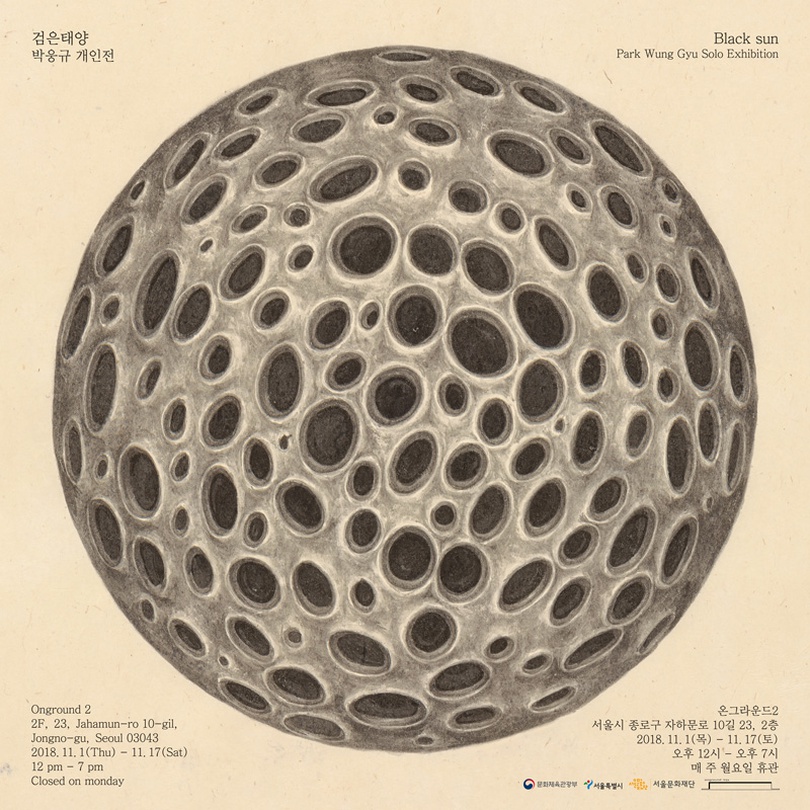

man-made. The spherical forms he uses to represent expelled phlegm resemble

intricately carved Chinese ivory balls perched on pedestals—but they’re actually

inspired by plastic Dragon Ball figurines. Dirty, yet dignified; traditional,

yet contemporary.

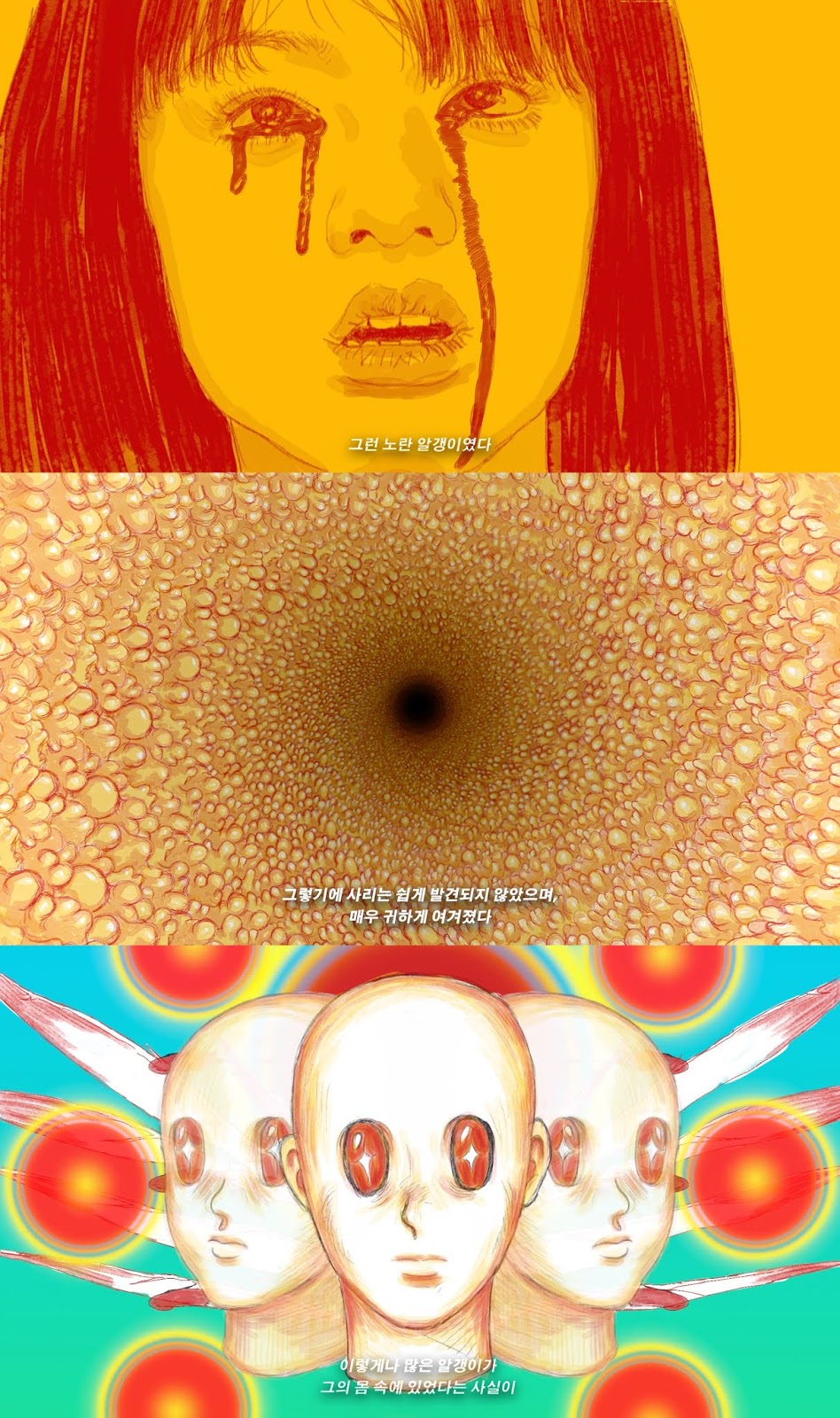

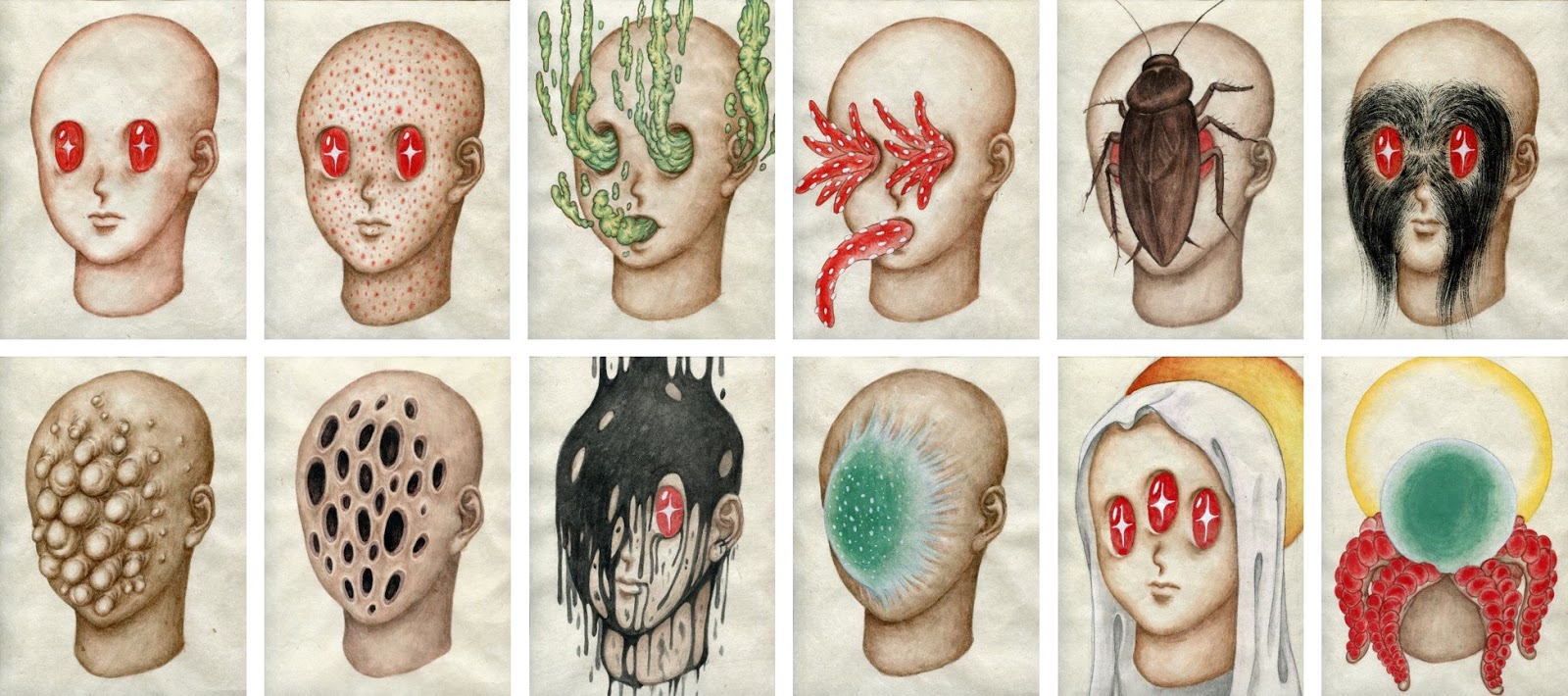

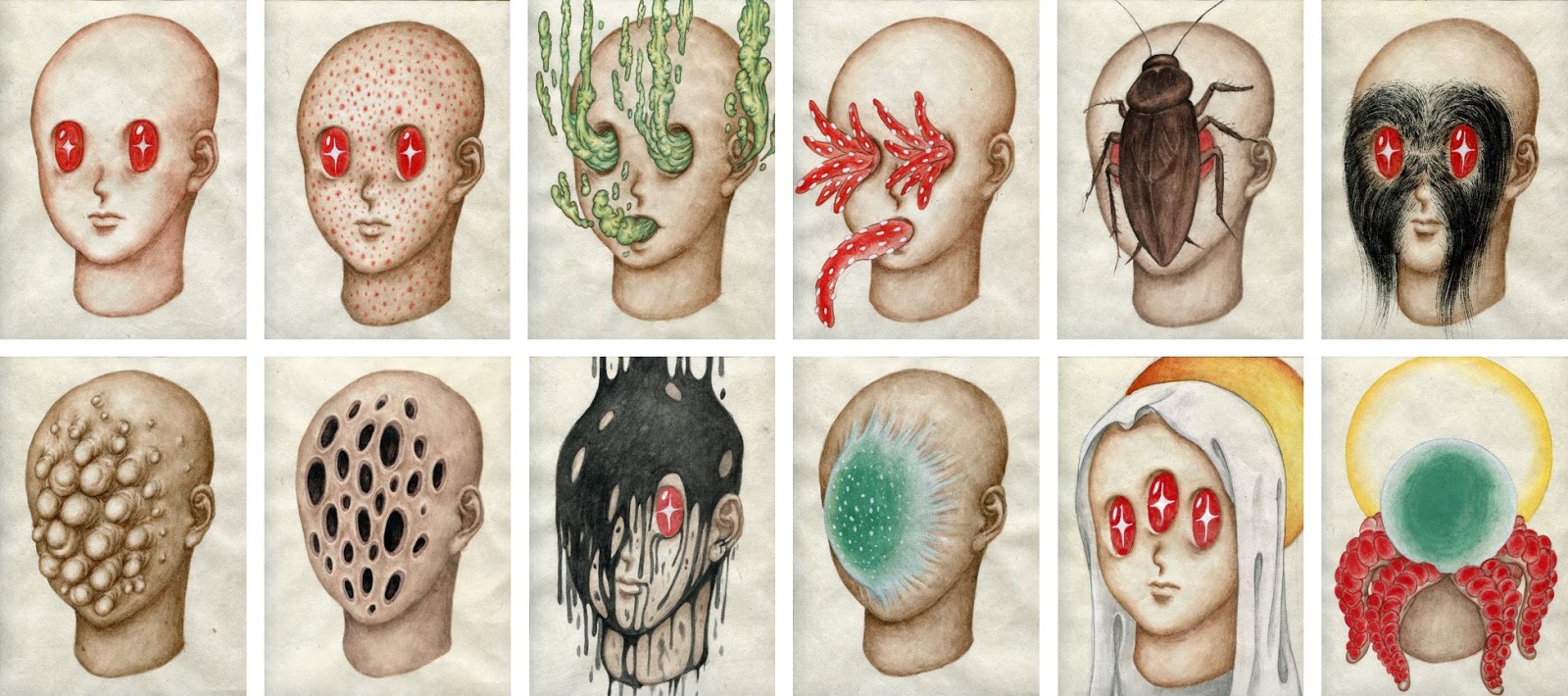

This fascination with the body eventually extends to the face. His

face series is animation-inspired. Big round eyes—two, three, sometimes

more—leak fluids or erupt in pustules. Insects, octopus tentacles, and hair

engulf the face. They should be repulsive, yet they’re somehow… cute. These

contradictions coexist in his work and generate another reversal when

experienced in person. What looked raw or grotesque in photographs was

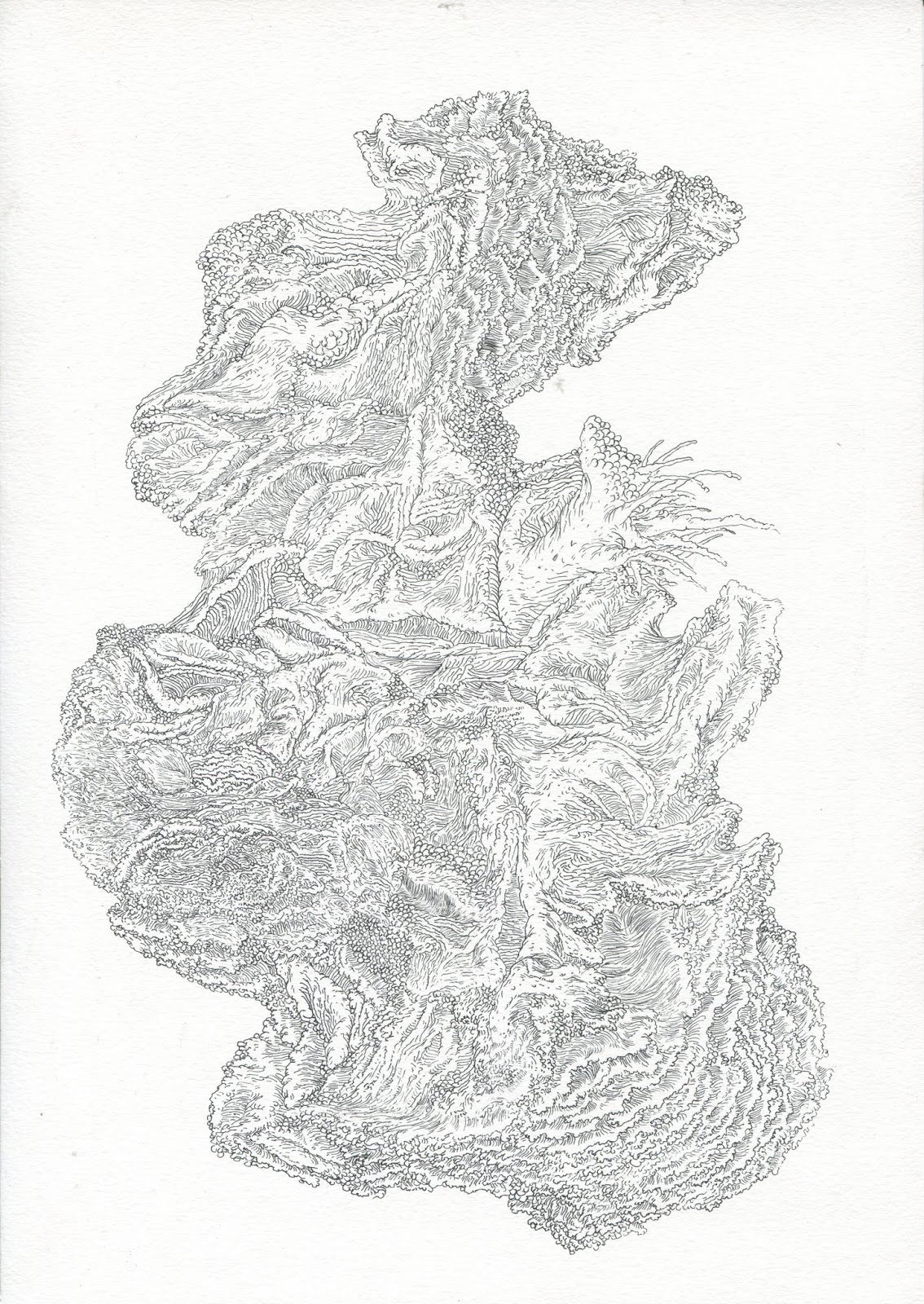

astonishingly delicate and serene in real life. Regardless of whether he’s depicting

a phallus, phlegm, or a monster, each dot and line was alive—crafted with

precision and devotion. What looked like Western painting was, in fact, an

intricate ink and pigment work on traditional Korean jangji paper. At that

moment, a fissure opened between form and content. His materials and methods

were completely detached from the shocking themes he dealt with. There was a

gap between what the artist wanted to say and what he showed. He wanted to

resist, but he was continuing tradition. The forms were obscene, but the

expression was sacred. And yet, this contradiction was not negative. In fact,

it was the surprise of this dissonance that moved me.