Kim’s works, which as such have been variations of an archetype

and an extension of the post-landscape genealogy, see a sort of a tendential

leap or discontinuity roughly around 2016. What is worth mentioning about this

period is the shift from figurative to abstract, or a pivot from figuration to

figurative abstraction, which also coincides with the change in her subject

matter. For the first time in 2016, she diverts her focus from evidence of

nature found in the city (or “leftover spaces” as she would call them),

dragging the axis of her work closer toward the heart of the city. For example,

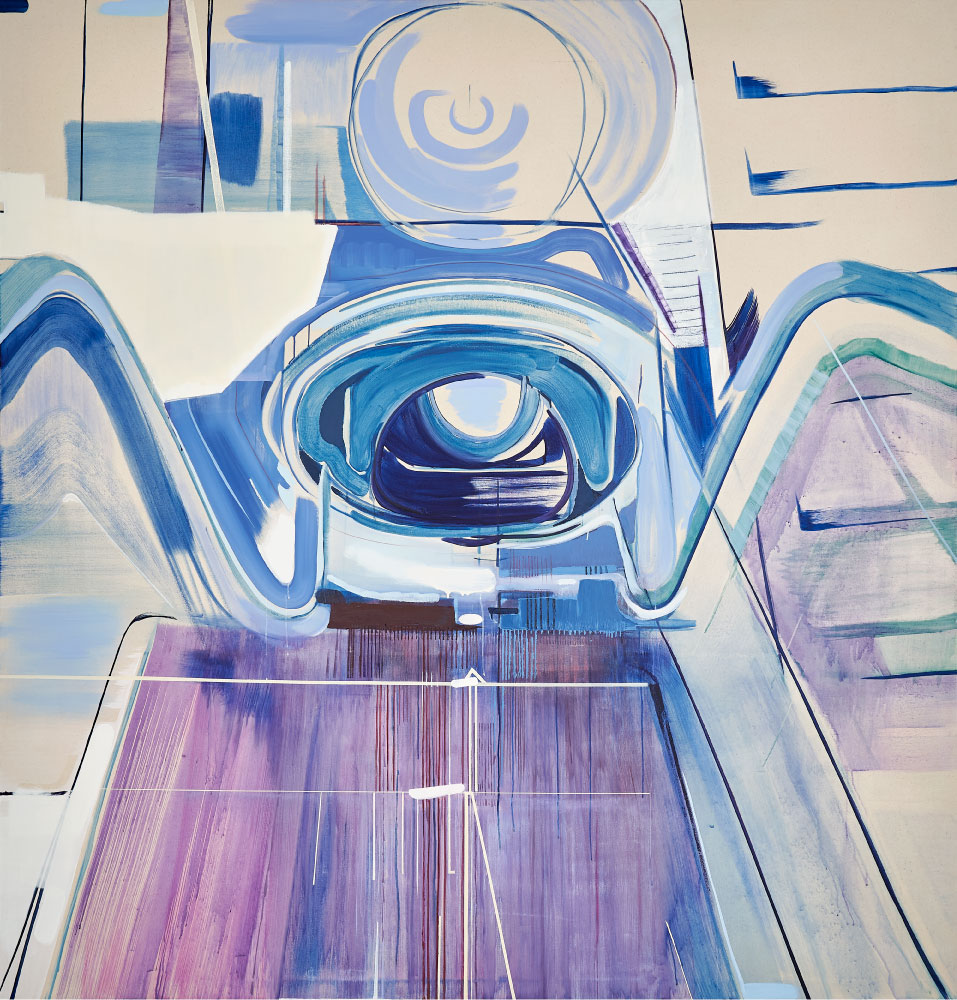

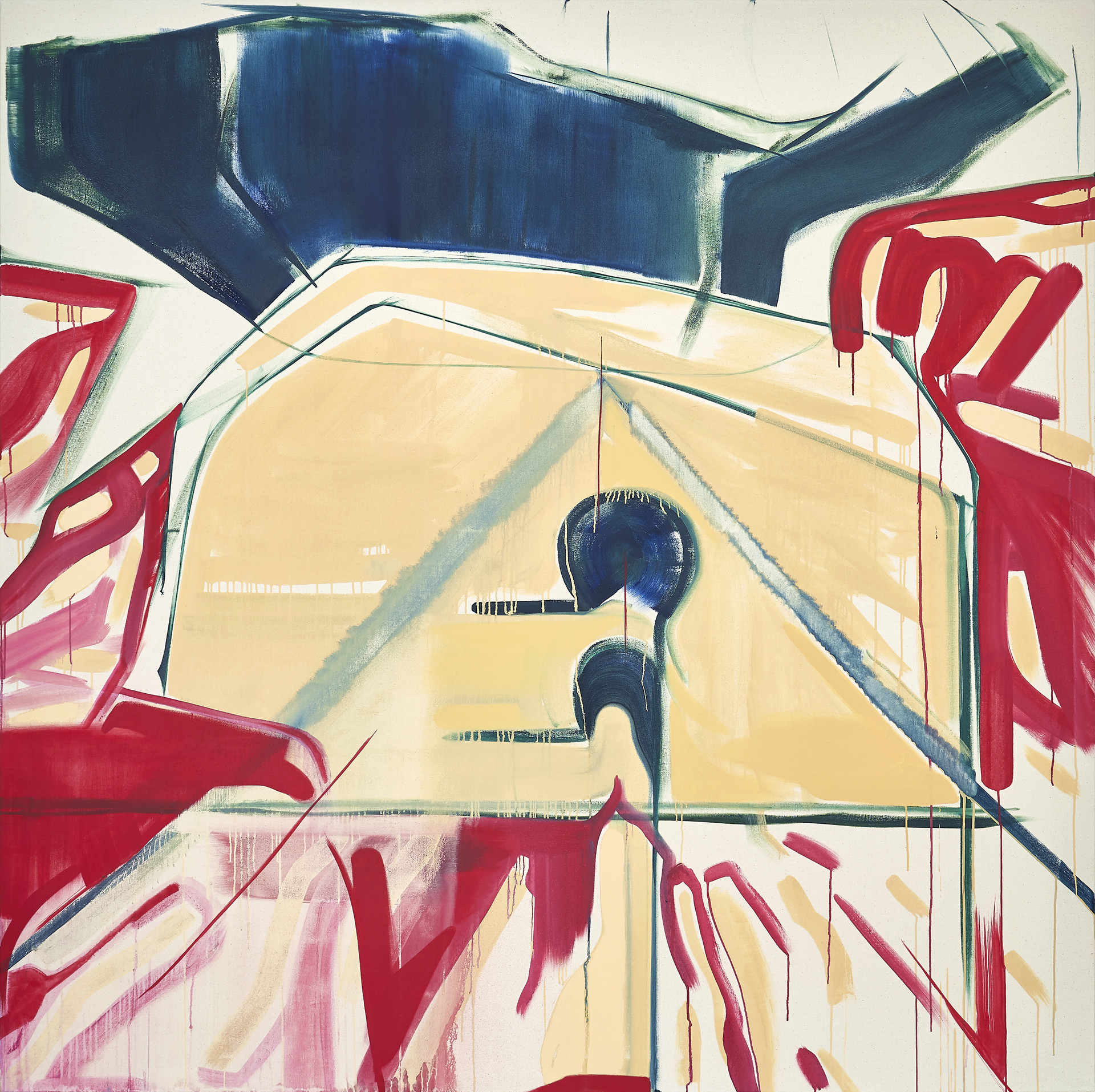

works like 〈Crack〉 (2016) and 〈Leftover〉 (2017) obviously capture parts of facilities that serve a purpose

in the city, but it’s ambiguous as to what the larger subjects are because the

forms are distorted almost to the degree of abstraction. As also demonstrated

by works such as 〈Division of Isles〉 (2017), 〈An Eye〉

(2018), 〈Grab and Run〉 (2019), 〈Inactivate〉 (2019), and 〈Hubble Bobble〉 (2020) each depicting an idle

parking lot, a tunnel, a passageway to a station, a construction site, and a

lower section of an overpass, her attention is largely directed toward the

retrorse aspects of the so-called “abstracted (modern) spaces.”

The subjects of her newfound interest circa 2016 were, so to

speak, spaces symbolic of forged experiences of modern temporality, more

specifically, the cracks in the hardly detected spaces or the compositional

exterior, the weak links. And here, we recognize foremost the “discontinuity”

as mentioned above—Kim’s imagery turning from “second nature’s mediation of the

first” to “fissures in second nature itself.” This, to quickly visit Freud’s

schema, seems close to a sort of reaction formation (defense mechanism),

because whereas the impossibility of first nature as a result of second

nature’s intervention points to the absence of an outside world, the fissures

in second nature point to the possibility of an inner outside world. In this

case, the discontinuity in the context of her work would signal an attempt to

find a room for possibility, an attempt to sail across the sense of despair

stemming from her early imageries. For example, the cracks, niches, holes,

fissures, and tunnels constantly explored in these works can be read as

allegories for an outward portal that transcends the existing urban premise or

as allegorical practices seeking to gaze at the possible exterior of the city

or modernity. In that sense, the fact that the subject of her interest shifted

from the “range of relationships among the roads, trees, and buildings”2) as

shown in her earlier works to the power, effect, and causality of the city’s

functional parts as shown in her later works is neither arbitrary nor

perceivable as a coincidence.