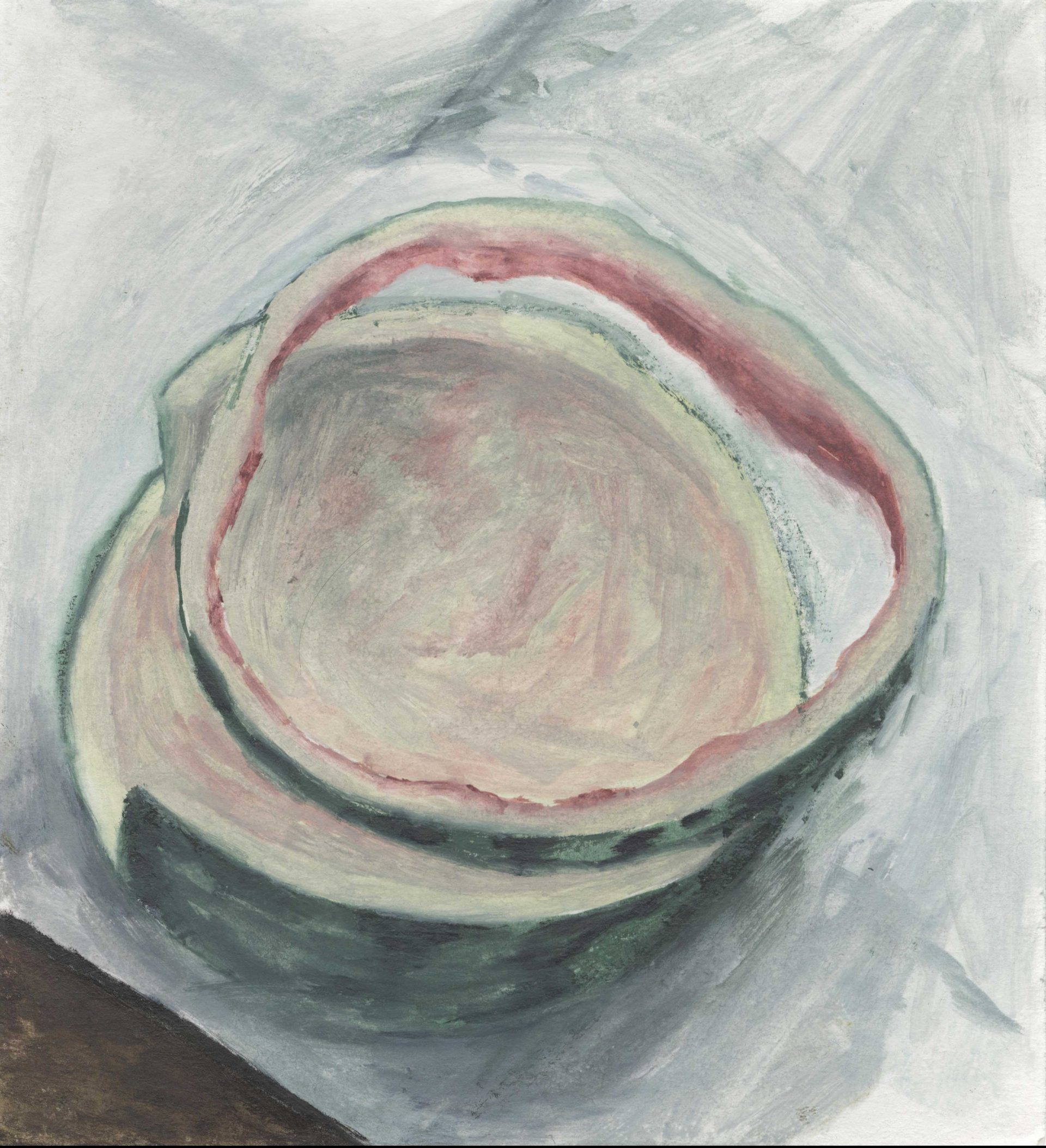

1. Painting of the (Old) Towel

The old towel that used to dry my face every day has lost its

tenderness and is now tangled, stiff and flat. When it dries, it reveals its

firmest texture and returns to its shape as if someone has laid it out. As days

and years pass, the bodily stains mixed with water leave a faint and dry

expression on a towel that once resembled the skin of an (innocent) animal. Is

there anything more boring than the dull and the dry? The figure that bears

only time remains uninspiring and bodes the once-delayed moment of extinction.

While rubbing one’s wet face, the repeated friction between the two exchanges

force and stains, each accepting changes in their forms. When the acts of

wiping, drying, and again, wiping and drying are all that happen between the

two, the fading and blurring (of one) become an inevitable legacy.

To recount an old and worn towel, which is as insignificant as a

dusty window, to such an extent, may seem more like an immature delusion that

sees the world and oneself with an aggrandized narcissism rather than an

attempt at humanistic rumination and reflection. The intimate and growing

imagination that takes place between “the towel” and “me (the face),” in a way,

implies a person's reservations about speaking more explicitly on the

fundamental undercurrents.

Noh-wan Park sent me four paragraphs under the title, “About the

towel painting.” In the last sentence (in parentheses) of his last paragraph,

he wrote that he hopes that someone will consider depicting a towel he used

every day on a large canvas to be a “lackluster joke.” Anyone who encounters a

colorful pink abstract painting with a blue hue mixed like stains (of time and

humidity) in the size of 290cm x 250cm will come extremely close to thoroughly

study the striking surface. This anticipation suggests a minor twist that will

soon reveal that “This is a towel” with a certain (new) clue attached to the

corner of the painting. The towel replaces a painting, such as an abstract

large scale color painting. He explains, “I just impulsively wanted to paint a towel

on a large canvas,” an old towel that I got from somewhere as a souvenir and

have used for a while.

With Huge Towel (2022) in front of us, he and I

continued our conversation in two folds. One was about the life of the towel,

and the other was about an old painting. When one spoke of the memories

attached to the towel, the other asked questions about painting, and the

conversation continued as if we were circling around the same place like

excuses and accusations. Park’s desire to simply paint a towel sounded like the

courageous determination to confirm (or reaffirm his intention of) the

conclusion that “this is a painting” under the premise and condition that

anything can be painted and by specifying the methodology and attitude of “how”

to paint. However, while doubting his delusions that he has dramatically

intersected the conditions of painting and the media methodology for it, he

puts off the gravity of a series of his pictorial achievements as a joke and

again, holds back. This supposed whim allows us to gauge the identity of Park’s

paintings - complex and its conquest - which has gained legitimacy through the

“painting of the towel.”

For several years, Park used a towel from “Bucheon Gwanglim

Church” that he brought from home while he was living on his own and came up

with the idea of painting it as an object of his large still life painting. The

fluffy and distinctively loose surface of the towel and the name of the church

printed in crude ink on its edge were directly transferred into the texture of

the painting surface and its self-governing formal logic, allowing him

imitation and identification (by large leaps and bounds). Memories of an old

church souvenir towel mixed with (historic and realistic) experiences of old

paintings construct a double consciousness on the “painting of a towel.” A

certain complex of these “worn” objects reveals his innocent fondness for these

objects along with a gripping obsession of them.

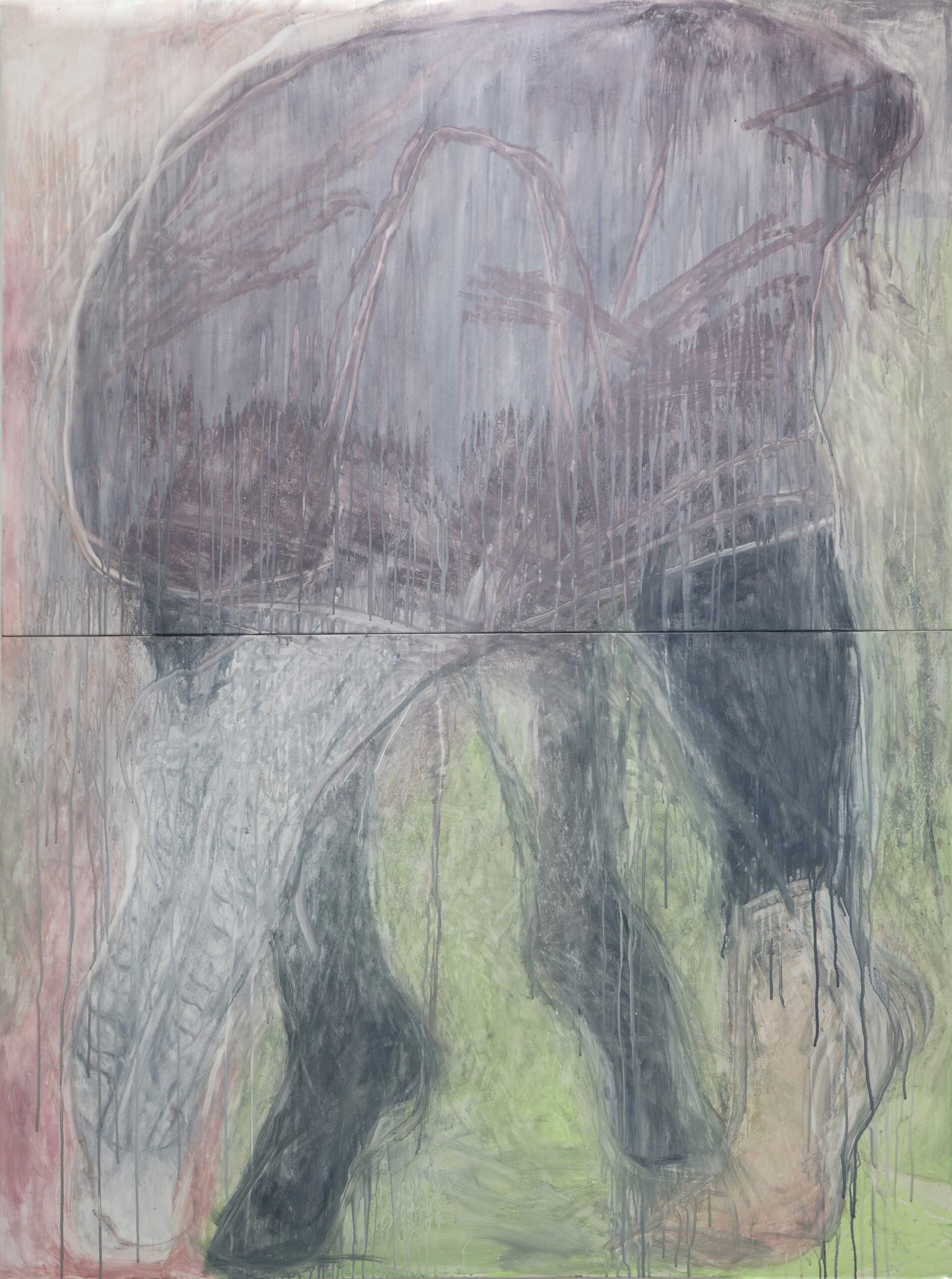

Umbrella (2022) and Boots

(2022) are the same. Park painted umbrellas and boots that were used until they

were worn out and broken. He cannot/does not throw away the boots with cracked

leather and worn soles and the rusty umbrella that barely closes. It is as if

he paints a canvas full of things that are no longer usable and replaces them

into images of ruins where everything has collapsed. At this moment, like

someone who tries to push an old object into the singular state (in the

material sense) and captures it onto an abstract image on the canvas, his body

intensely pours out the lifeless image of reality (such as the ruins) onto the

still surface of the painting.

2. Until It Fades

Park's Huge Towel has (blue) stains. This tint

seeps all over his painting. He explains that they are rather blemishes that

discolor the painting, but when studied carefully, the blue shade fades the

entire painting into a hazy, unexpectedly abstract feel. Perhaps the blue

stain, in essence, critically transfuses the helplessly tarnished image of

reality that has been inserted into the painting’s plane as an abstract

painting, like the experience of (re)recognizing the huge square pink canvas

through the blue ink used for the text “Bucheon Gwanglim Church” that sits

within the Korean Christian Methodist Church.

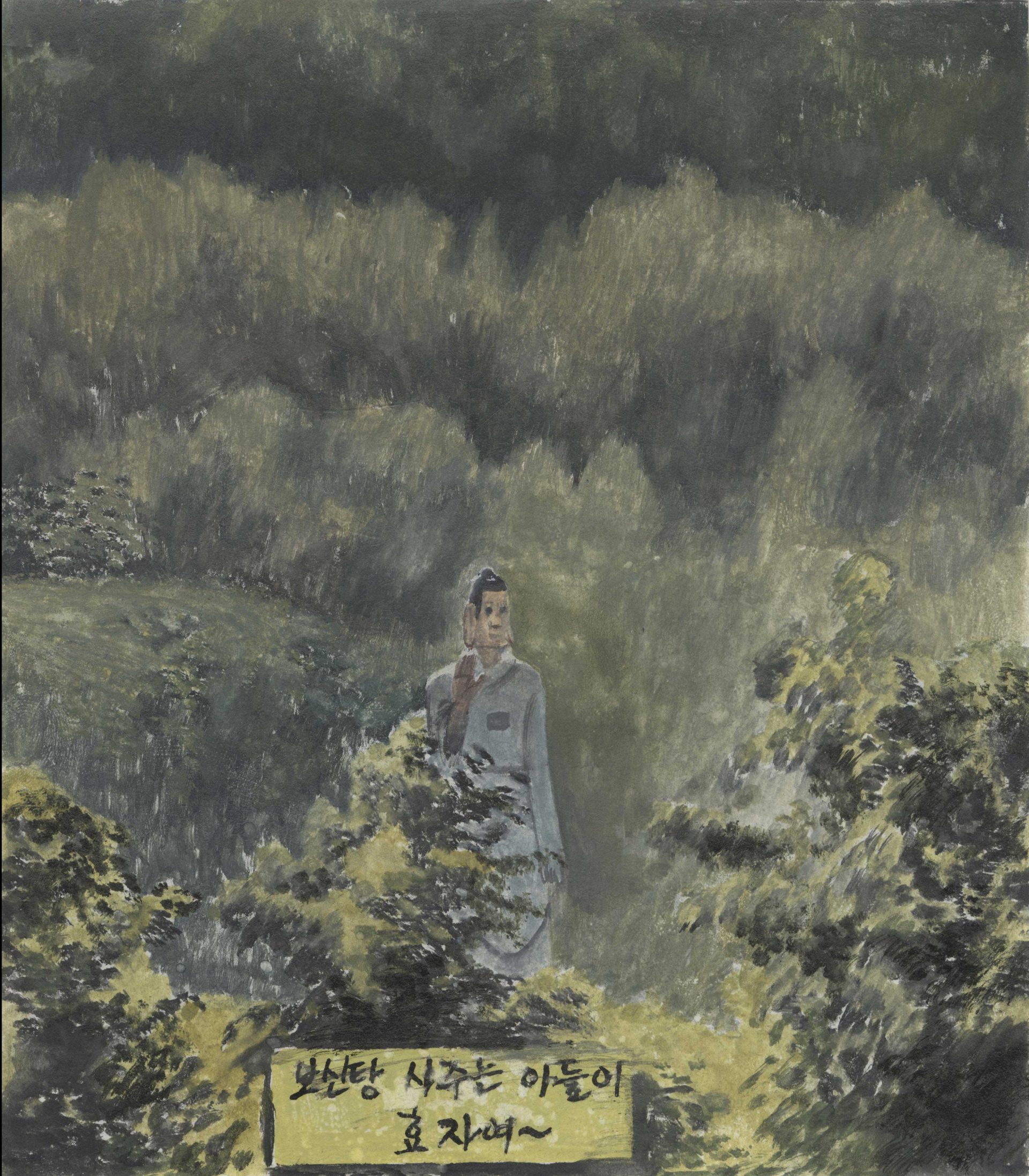

At a closer look at both series Part of Church Flyer

(2022) and Images about Stem Cells (2022), you can see the

blurry blue outlines that fill the painting’s canvas. Church Flyer

No.1, 2, 3, a series of paintings of a part of an evangelist church

leaflet that was found on the streets, were drawn on three parallel canvases

like a three-sided painting, and Images About Stem Cells No.1 and 2

are images of a medical advertisement found on the road. His method of

discoloring the surface of the painting through the blue outlines slightly

differs. Largely speaking in two terms, one is continuously erasing/wiping the

outlines by mixing them with other colors, and the other is forcing the outline

of the figures (which was emphasized in the previous works more) into the

canvas. While these two advance separately, they in fact operate

simultaneously. The church leaflet from the streets divulges the worldly desire

for heaven in a lowly and explicit manner while seeking to share the gospel of

transcendent redemption and God’s salvation; Park intentionally shares this

“failure” by substituting the broken reality and (in fact) malfunctioning world

of salvation into the pictorial scene.

To sustain this failure, he uses watercolor that can melt on the

surface of the painting at any given moment. After securing the texture and

thickness by mixing liquid rubber with the watercolor paints, he obsessively

repeats the painterly labor of drawing, wiping, and drying it until the surface

of the painting becomes hazy. When the blue outlines and other watercolor

paints blend in as if these forms are fused together, Park’s painting does not

lose the tension between the fading of the painting’s surface and the

abstraction but rather makes use of this situation as an excuse to find the

delicate point of balance. This maneuver is also connected to his choice to

degenerate the painting by distorting the shape, as visually prominent in the

Images about Stem Cells series. Park is intensely mindful of the edges of the

canvas. This 2-dimensional limit allows not only the possibility of an abstract

color painting but ironically also the conditions of deterioration. In other

words, during the process of painting the figures with blue outlines on a flat

canvas, Park intentionally invites their distortion that conforms to the

painting’ frame without seeking a perfect representation or structural

perfection. Through these intentional pictorial failures, he weaves the

deteriorated abstraction into fragmentary painterly language.

Untitled (2022), Dried Carrots and

Cabbage Leaves (2022), and Ice Cream Promotion Balloon

(2022), which depict decorative plaster statues sitting by the window, are

consistent attempts to introduce the already deteriorated objects found in

reality into the pictorial realm.

From an “imitation” of worn objects that replicate, replace, or

resemble something, the artist crosses the series of circumstances in which

contemporary painting has been placed in. The painting and wiping of the

watercolors until the subject becomes blurry in the flat conditions of his

painting do not merely restore the deteriorated form in the pictorial sense. In

fact, he must be risking his own blurring by melting and damaging the old

surface of the painting, which has become as stiff as an old towel, and

locating where more stains could be drawn onto the painting. In a more grand

sense, it must be the infallible mission given to an heir of the painting’s

stains.