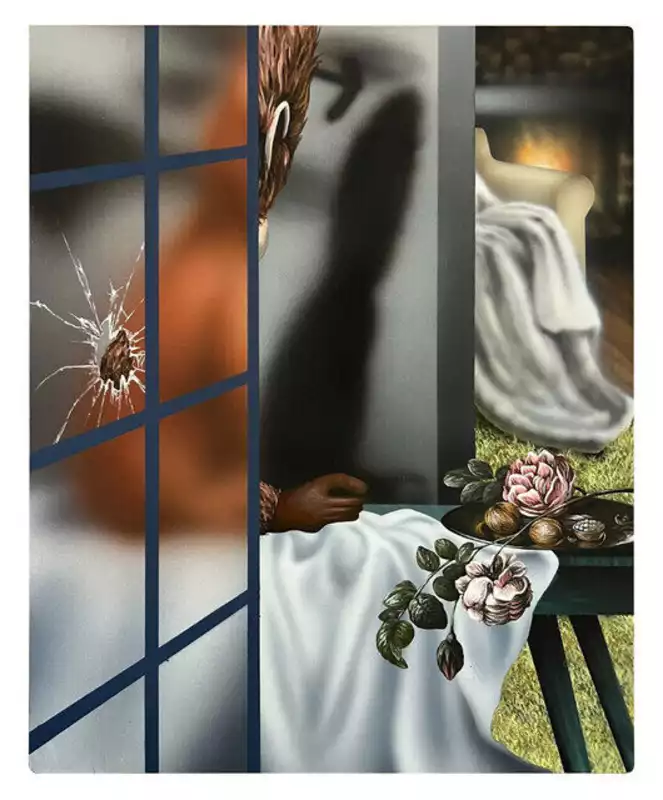

Often sourcing personal memories,

physical images and personal data of others freely available on social media

platforms, Sun Woo merges these disparate remnants together through

digital-like process of alterations and edit, to create a mediated interface on

her canvas. While her microscopic precision of detail obfuscates the “realness”

of her canvas paintings to that of a Photoshop artifice, the prolonged physical

labor to transform her digital collages into traditional modes of presentation–

painting and sculpture–depict a longing to delay and obstruct the fleeting and

transient nature of the contemporary condition. Through this synchroneity

between technique and technology, Sun Woo opens a liminal space where the

experience of duality is possible, sparking a nuanced reflection on both

internal and physical dislocation.

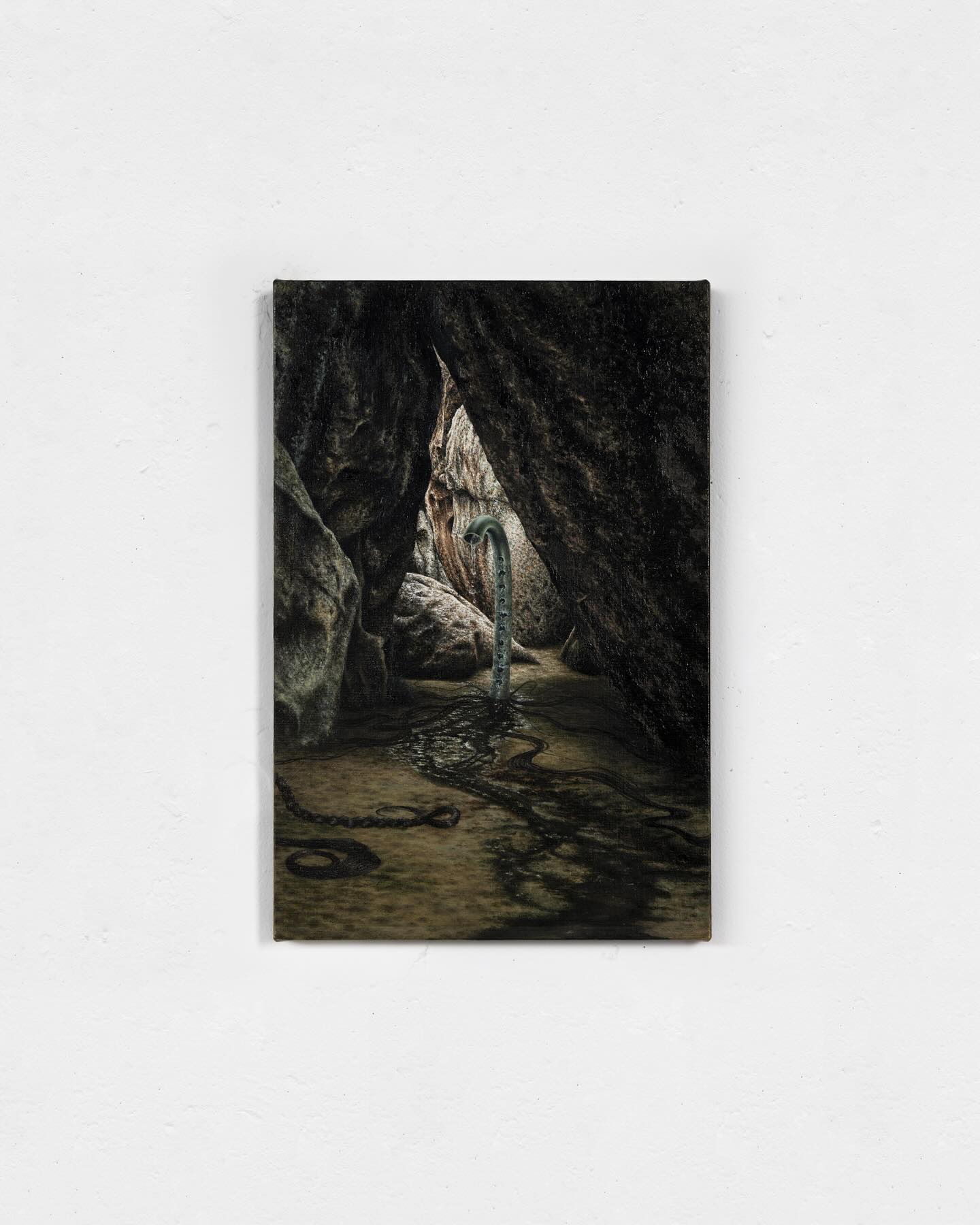

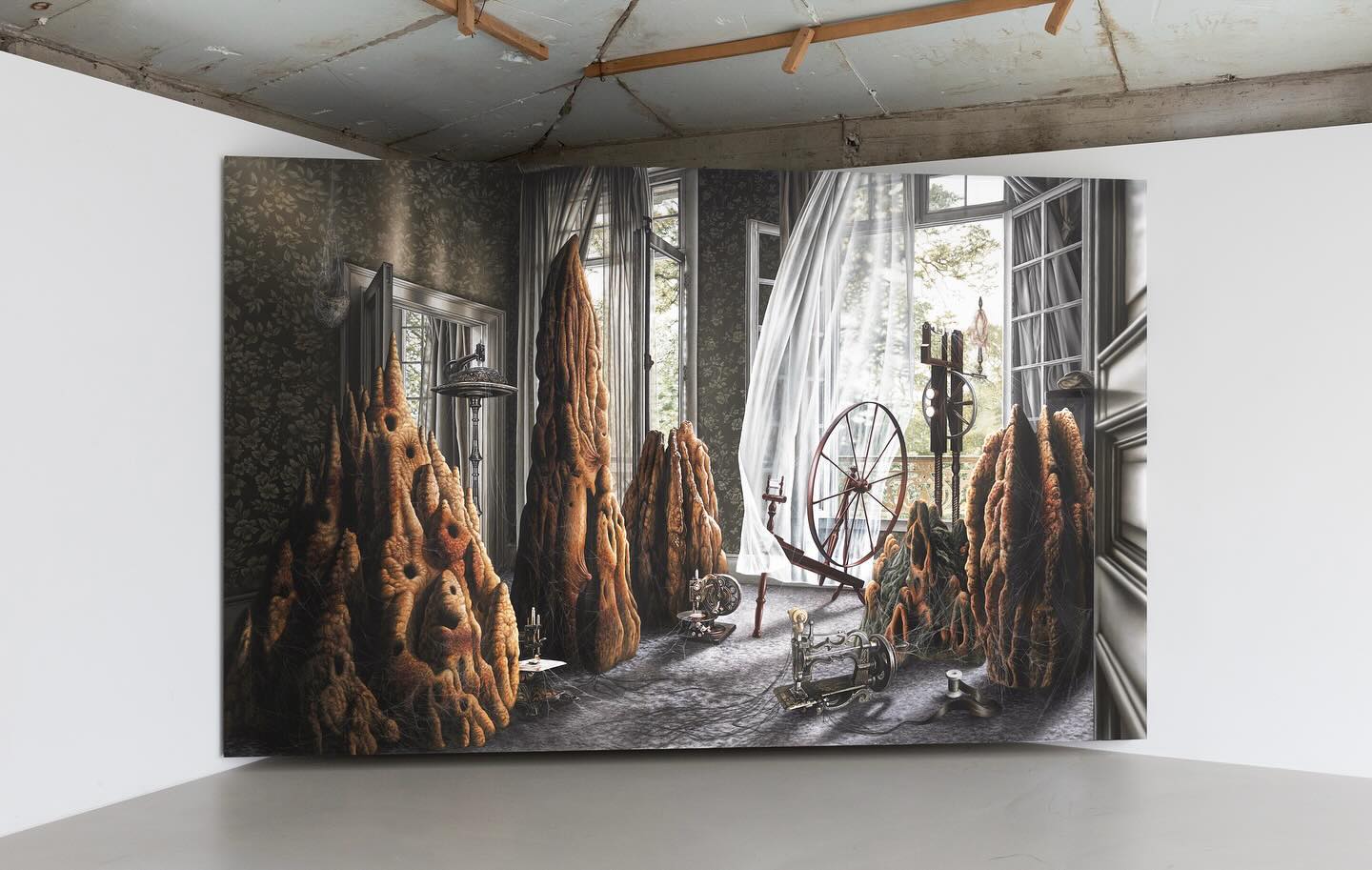

In her large-scale paintings, Sun

Woo merges bodily elements with geological formations like sea caves,

coniferous forests and objects, both vintage and modern, to form mesmerizing

visual paradoxes that defy conventional logic. The Chorus (2024),

which details orchestra instruments submerged in a sea cave, evokes a feeling

of displacement between civilization and nature, the interior and the exterior,

the familiar and the strange. These objects are further embedded with

human-like features: hair drooping from the grand piano, smoke exhaled through

the flute, and water expelled like bodily fluid from the horn. While such

detail encourages one to relate to one’s own body, the overall hybridity breeds

a sense of anxiety, impotence, and decay related to human transience instead of

intimacy.

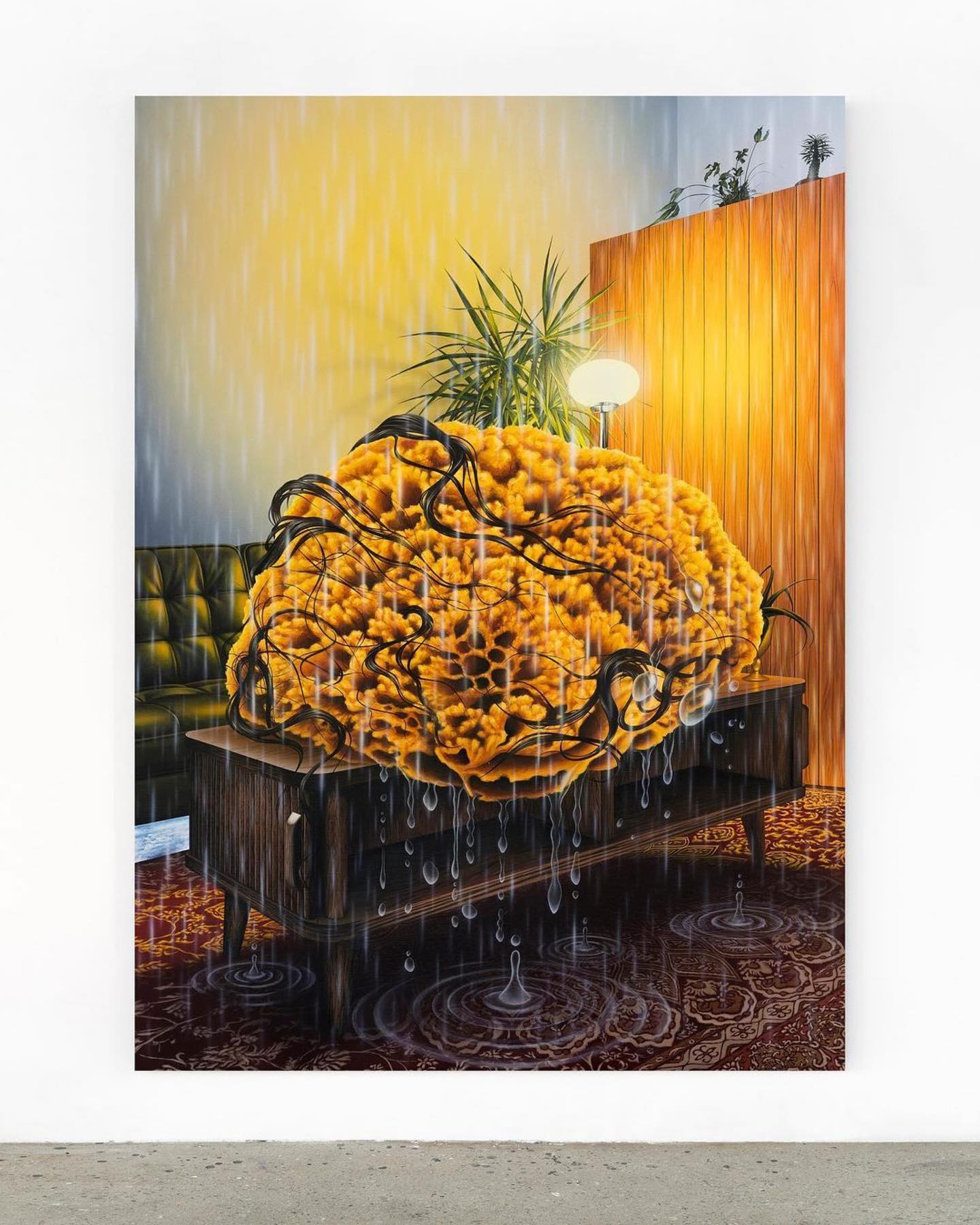

At the same time, there is an

undercurrent of violence toward the body that repeatedly haunts her works. The

effect appears most pronounced in Shivers (2024);

the slit within the haystacks of which bears an uncanny resemblance to the

female orifice or an open wound, is brutally penetrated by twigs, while robotic

snow blowers chill these bodies in extreme closeups. Such catastrophism

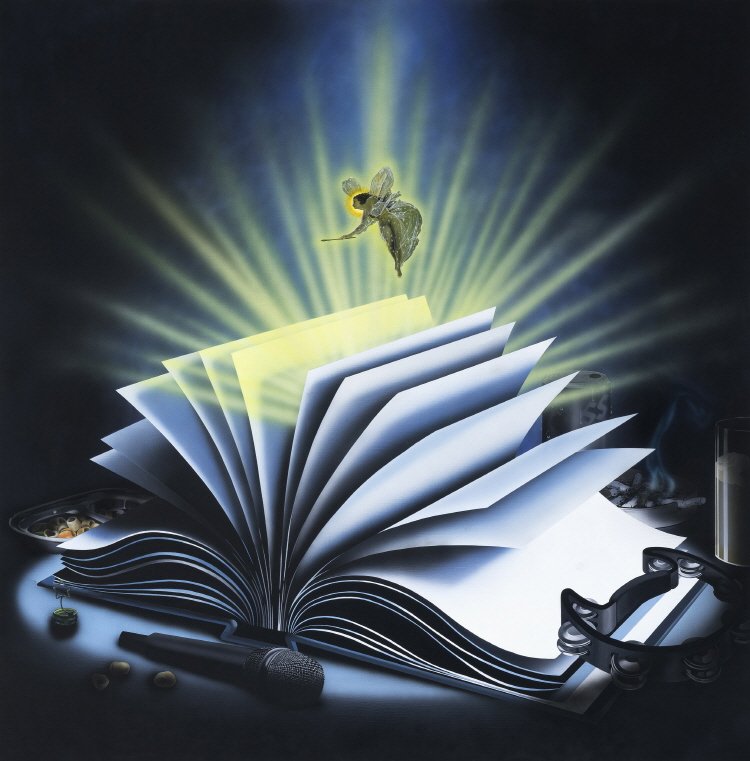

reappears in her other works, as seen in Rest (2024),

the rocks’ colossal weight tensions a supporting braid from the trampoline bed

to the brink of snapping; and in Mother and Child (2024),

a vintage scale weighs between two portions of hair which, as implied by its

title, belong to a mother and her offspring. In all three cases, Sun Woo weighs

down and overwhelms components of the female body to elicit a mediated

condition of one’s memory, history and identity, playing on such mismatch in

order to reflect the politics of female sexuality. She also depicts these

figures as stranded in unknown wilderness, recollecting the landscapes of the

suburban West where she grew up as the only woman of color, portraying them as

places of both nurture and menace. Alongside the implications of gravity and

mortality, these in-between states also suggest fissures in rigid boundaries,

highlighting moments of potential rupture.