A Shipwrecked Civilization and a

Cosmic Wanderer

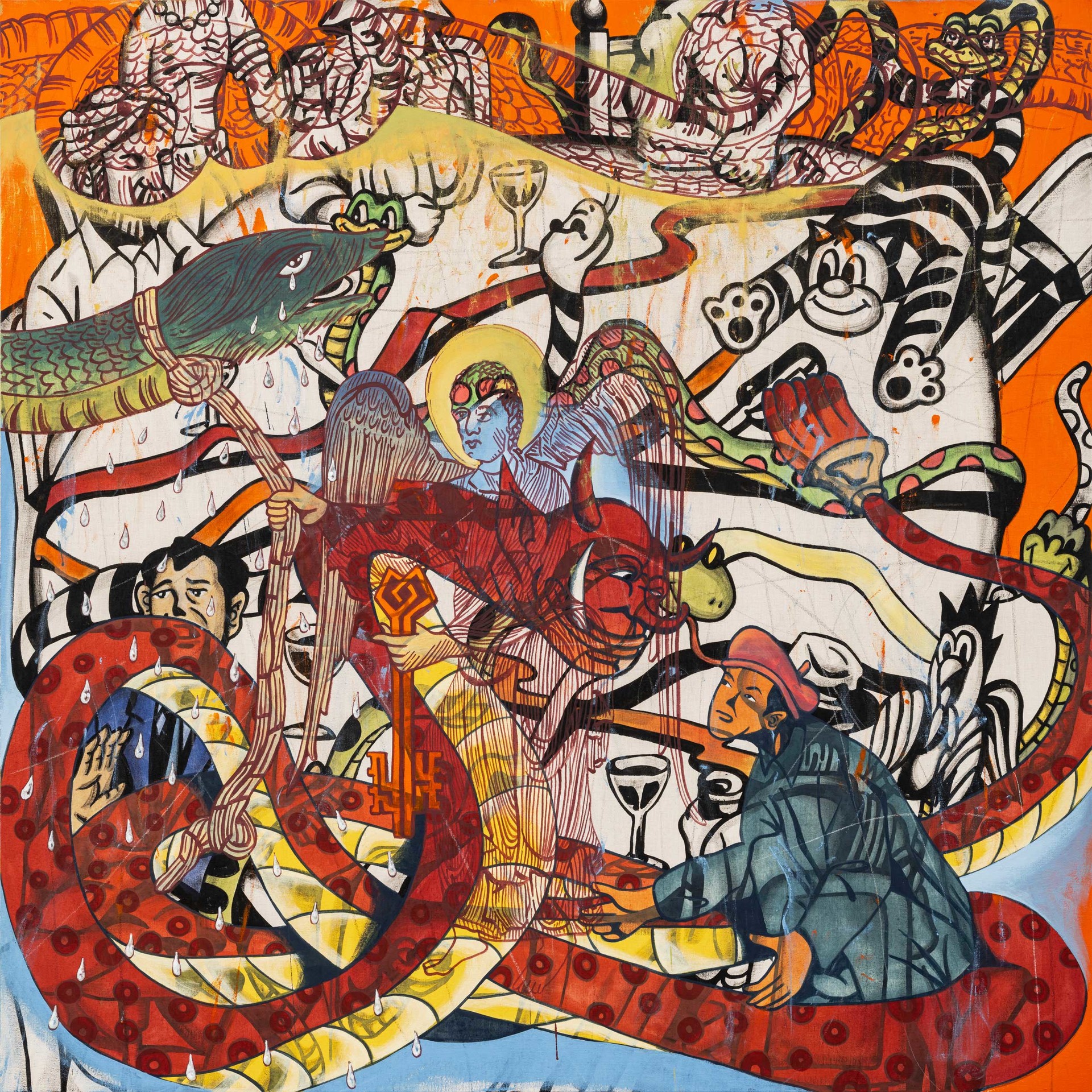

Books stacked tightly in a

library collapse, and in the midst of the debris of books and objects pouring

out from a wrecked ship and drifting across the sea, carnivorous animals appear

and engage in a bewildering struggle with books. This highly unrealistic scene

summarizes several impressions from Jeongsu Woo’s solo exhibition 《The Grave of Books》. The collapsing library

in his paintings evokes Borges’s imagined Library of Babel.

Interestingly, the etymology of Babel in Hebrew means “chaos.” It seems that

Borges, in conceiving this library, had already predicted the future of

humanity. Humanity’s desire to be saved by the endless world of civilization

and knowledge—yet never truly attaining it—resonates with Woo’s work. The

tightly packed books in his paintings metaphorically represent the culture and

civilization built by humankind, as the Library of Babel

suggests. The linear historical view that once believed in the inevitable

progress of civilization has already crumbled today. Amid global crises,

disasters, and catastrophes, there is little expectation that human knowledge

will overcome the current predicaments and lead to a radiant future. The

artist’s attitude toward this situation neither screams despair nor seeks hope.

“Neither descending nor ascending, but in an intermediate state”—this phrase

refers not only to the structure within the paintings but also to the artist’s

determination to examine the situation of individuals adrift in the chaos of

the world. This exhibition, 《The Grave of Books》, begins with a skeptical view of humanity, ominous signs from

around the globe, and above all, the existential anguish of one individual

sensing these conditions.

From One Drawing to One

The starting point of the

work lies in a shipwreck. This imaginary situation traces back to a drawing

book created by the artist himself in 2010. In over a hundred drawings, which

seemed to pour out the images in his mind at the time, the artist depicted

scenes filled with contradictions and absurdities of the world—death, violence,

chaos, oppression, destruction, confinement, conflict, and more. These drawings

unfold like works of fantasy literature and were inspired by the countless

books the artist obsessively read in his attempt to understand the world. Just

as the title of his 2015 solo exhibition, 'Pictures of Rogues,' referenced

Borges’ 'A Universal History of Iniquity,' the title of the current work also

echoes many of the books he devoured: Pascal Quignard’s 'The Roving Shadows,'

Botho Strauß’s 'Time and Room,' Daijiro Morohoshi’s 'Fish of the Night,' among

others—spanning literature, comics, plays, and historical texts. It is no

surprise that books frequently appear as motifs in his work. To the artist,

books are not only the world, civilization, and a mirror of desire—they are

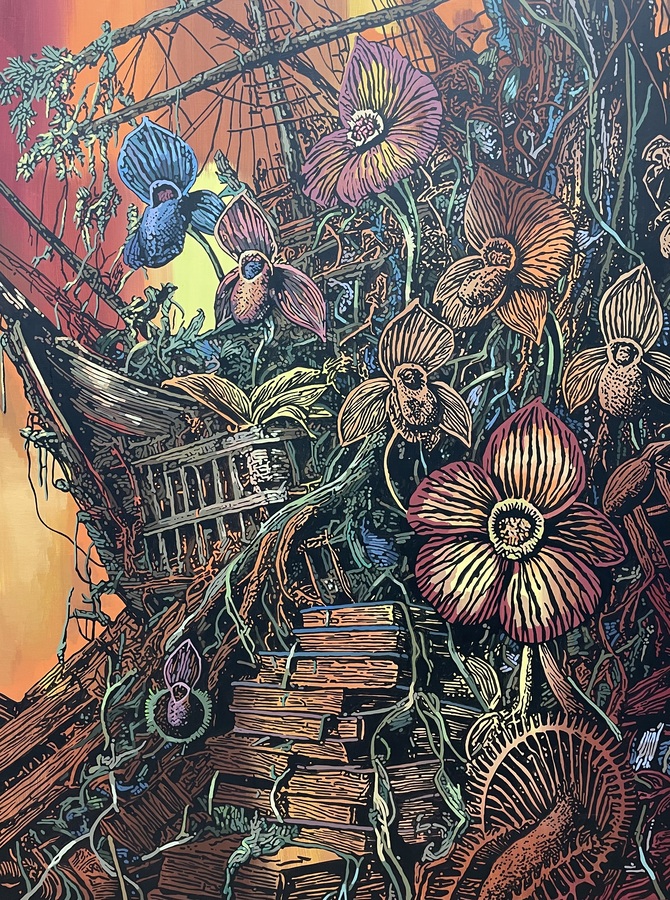

also the foundation of fantasy and living spirits. One of the early drawings

depicts books washed ashore from a shipwreck piled high, intermingled with

skulls, as two men armed with long poles confront each other tensely. This

drawing is what he would later call 'The Grave of Books.'

The artist’s statement that he

'wanted to show a single painting' is rooted in this small pen drawing. Having

trained in various media—pen, pencil, charcoal, oil—he has focused primarily on

ink since 2014. To this artist, who aimed to counter the weighty subjects of

the world with a light touch, ink became an intuitive tool, allowing emergent

forms to be expressed with ease. In his smaller drawing works, the force,

intensity, and feel of the hand manifest freely through the ink, producing a

satirical atmosphere that borrows from subcultures. In more recent works,

however, this spontaneous brushwork is deliberately restrained. Perhaps in

painting 'a single image,' the artist has developed a sense of patience,

balancing the sensory interplay between ink and hand. It was through this

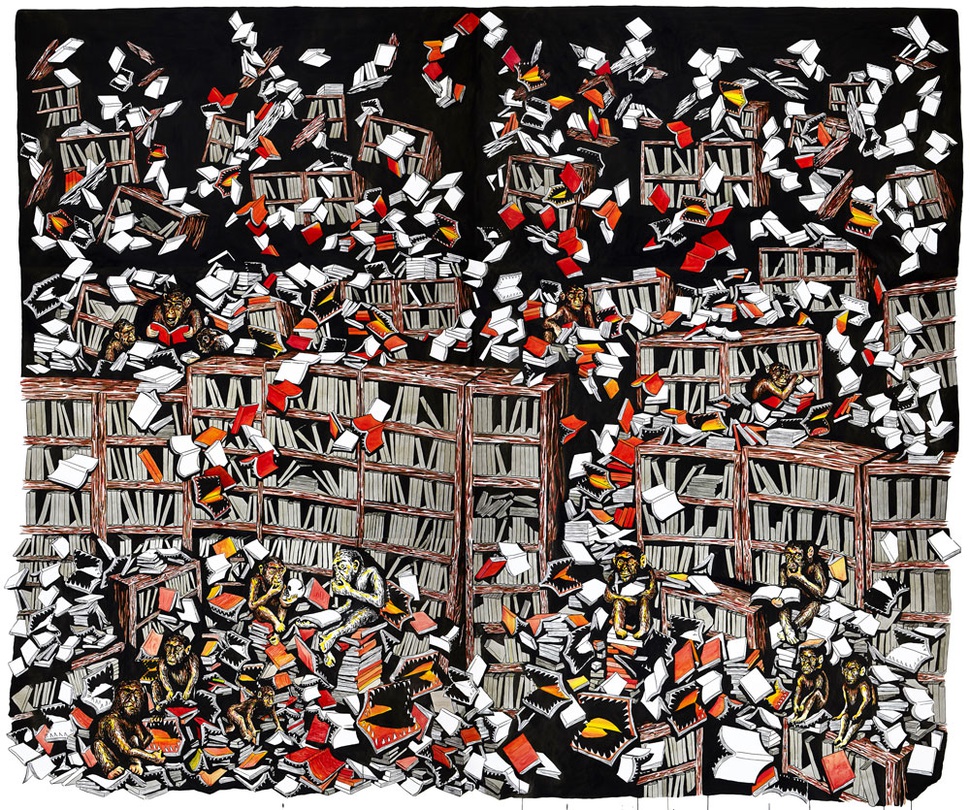

process that he completed the large-scale painting 'Monkey Library' (5 x 5 m).

Carefully regulating the weight of the black ink across the entire canvas would

not have been an easy task. Working on a narrow wall in his studio, he affixed

one sheet of paper at a time, meticulously calculating the composition between

chaos and order. This working method likely became a meditative time of

discipline, balancing between a 'sense of reality' and a 'sense of

imagination.' The exploration of duality extends not only to the materiality of

painting but also to the image-making process. 'Monkey Library' represents an

effort by the artist to suppress personal expression while experimenting with

both the 'sense of decomposition' and the 'sense of construction.' This static

yet dynamic composition is carried through not only in the painting’s visual

field but also in the overall exhibition design, which mixes drawing and mural

elements.

The World of Madness Emerged from

Shipwrecked Civilization

Returning to the shipwreck: in

the exhibition, 'Shipwreck G' takes its name from the fictional ship 'Glory,'

imagined by the artist. Judging by its name, the ship must have once been

splendid, but it was suddenly destroyed by catastrophe, its fragments drifting

across the sea. Statues, relics, and books—symbols of a glorious past

civilization—float among the debris. The 'glories (memories) that are sinking

and disappearing,' as expressed by the artist, do not simply end in submersion.

It is here that Jeongsu Woo’s painterly sensibility is fully revealed: the

light touch that satirizes the outbursts of violence amid despair. The sunken

ship does not sink so easily. Like many facets of our own society, tragedy only

begets more tragedy, and dehumanizing horrors rise to the surface. In 'Time of

Carnivores,' a pack of crocodiles suddenly appears and attacks the books.

However, the books have sharp teeth of their own, making it impossible to

determine whether the books are devouring the crocodiles or vice versa—only an

overwhelming violence remains.

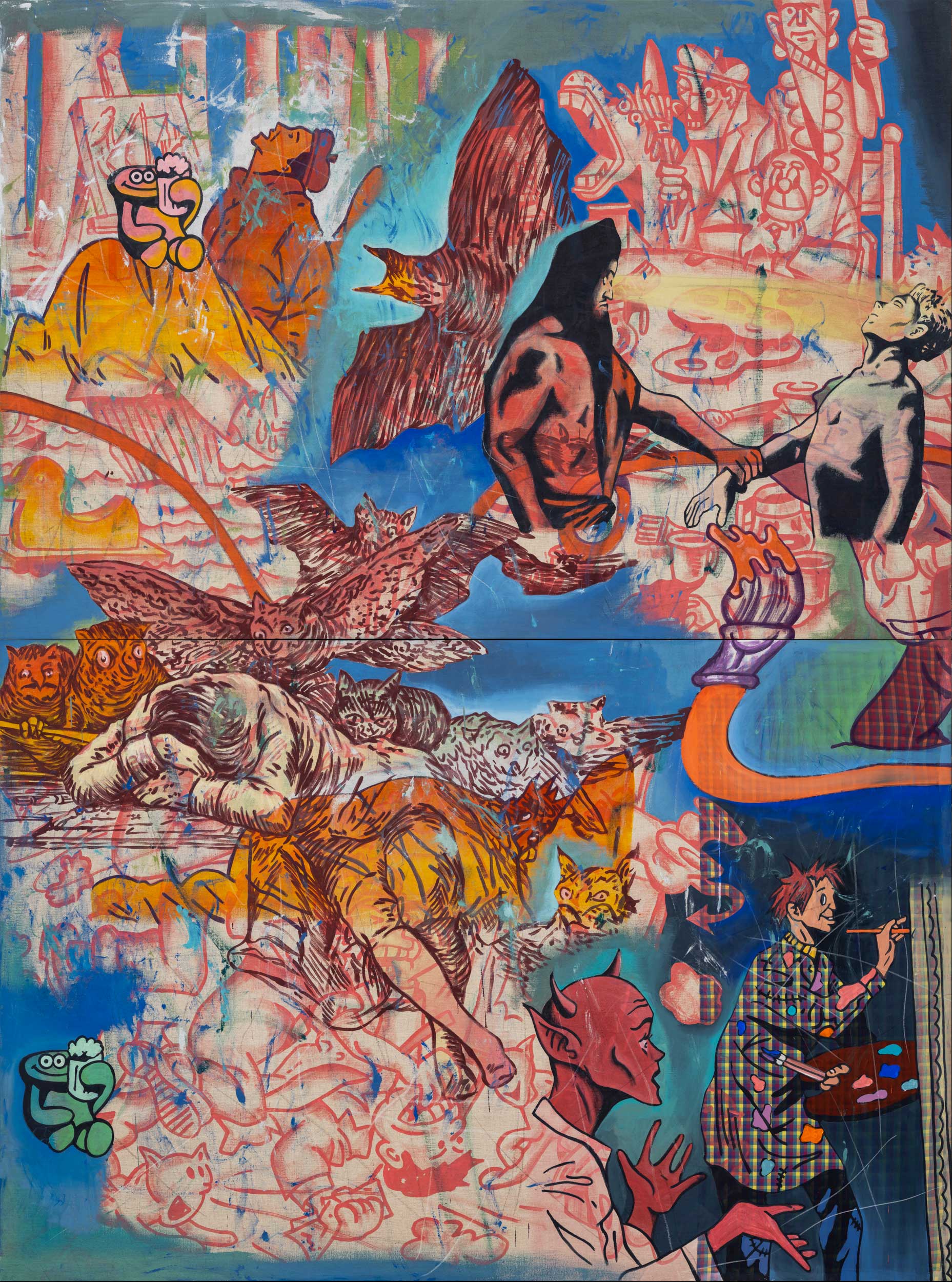

Observing this chaotic violence

is the full moon, left as an empty hole. This moonlight motif continues across

several subsequent works. Its presence foretells the onset of events (or

narratives) that follow the shipwreck. In 'The Battle of Punta del Cota,' a

giant octopus shatters the ship; in 'Time of Carnivores II,' an eagle

cannibalistically devours its kin; in 'Ghosts of Books,' phantoms overflow from

the drifting books. These grotesque and uncontrollable monsters, spirits, and

apparitions emerge as a result of a world whose order has collapsed. They push

an already chaotic situation into further disarray, consuming even the drifting

meanings. Amidst all this, in the monumental 'Monkey Library,' books quite

literally fly, fall, and float in a state of confusion. As chaos and order

clash, the monkeys, as if mocking the meticulously built human civilization,

take over. The primitive world and grotesque fantasies that emerge from the

chaos of civilization escalate into full-fledged events.

The World of Vortex and Chaosmose

The first piece viewers encounter

upon entering the exhibition is 'Night Owl,' which sits on the threshold

between before and after the unfolding events. The exhibition’s layout is

organized such that the owl separates the present and future of the wrecked

objects. The previously described works represent the present state of the

shipwreck. The owl perched atop 'The Grave of Books,' gazing at us, seems to

signal an ominous forewarning. This uneasy calm is short-lived, as the

shipwreck fragments are soon swept into a powerful vortex ('The Roving

Shadows'). Inside this whirlwind, books, statues, and relics are stripped of

all meaning or symbolism, reduced to debris caught in turbulent motion. The

swirling speed of the vortex manifests in the painting as white bands that

engulf the floating objects. From this point, the full moon is no longer

visible. Did the moon’s hollow light projector cause this spiral of beams? The

swirling white light in the darkness evokes Paul Virilio’s ideas. He once

described the image in painting as an 'aesthetic of appearance' and in film as

an 'aesthetic of disappearance.' The moon’s lens-like hole and the vortex’s

light beam—both immaterial in form—collapse the emergence of things into a

whirlpool of disappearance.

All of these stories culminate in

the highlight of the exhibition: the 9-meter-wide mural 'The Task of

Narrative.' Arriving at this point after passing through the vortex, this

massive wall painting takes the form of a 'world drawing'—combining five

pre-produced drawings with a mural painted on-site. 'The Task of Narrative,'

sprawling like a cosmic expanse, represents a world after chaos. The many

objects of the shipwreck now drift through the universe, beyond the open sea.

There is no center, no rising or falling—only floating. What shifts this

suspended state is the appearance of a massive meteor. Silently traversing the

chaos at light speed, the meteor draws a luminous band across the sky. This

ribbon, created by the meteor’s trajectory, imposes a new order onto the chaos,

embodying a form of 'chaosmose'—a cosmic flow that is at once disorder and

order. At this point, we begin to understand why the artist envisioned a mural

of this scale. Jeongsu Woo seeks to guide the viewer’s physical body into the situation

of the painting. As a flâneur wandering the city, he translates the world he

experienced among people into a spatial form that invites participation in the

exhibition. As the viewer walks, they enter the world of the painting and, like

the drifting objects, may become part of the luminous ribbon. Here, the

boundary between the world of representation, illusion, and the dimensional

reality begins to dissolve. Walter Benjamin once wrote of the dream-image of

the modern city, urging us to 'awaken from this dream.' In this single painting

(or exhibition) that Woo has created lies both the fantasy that dissolves the

image of the world and the fantasy that attempts to summon it into being.