Just like the snow falls all

through the night and puts footprints down on the white field that no one has

yet stepped on, the thin and fine lines deftly go across the white paper and

then black shapes fill the screen soon. Through the nib of pen, this reveals

itself on the plain surface of the paper. It repeats itself as an infinite

chain of unknown symbols and then disappears―sometimes in the shape of man, then as goblin, bird, sea, sometimes

forest, then goblin again, and sometimes book, monster, monkey, and the

self-portrait of the painter. The innumerable drawings that fill the whole

floor of the exhibition hall convey the meaning of each one through the loose

link of a book.

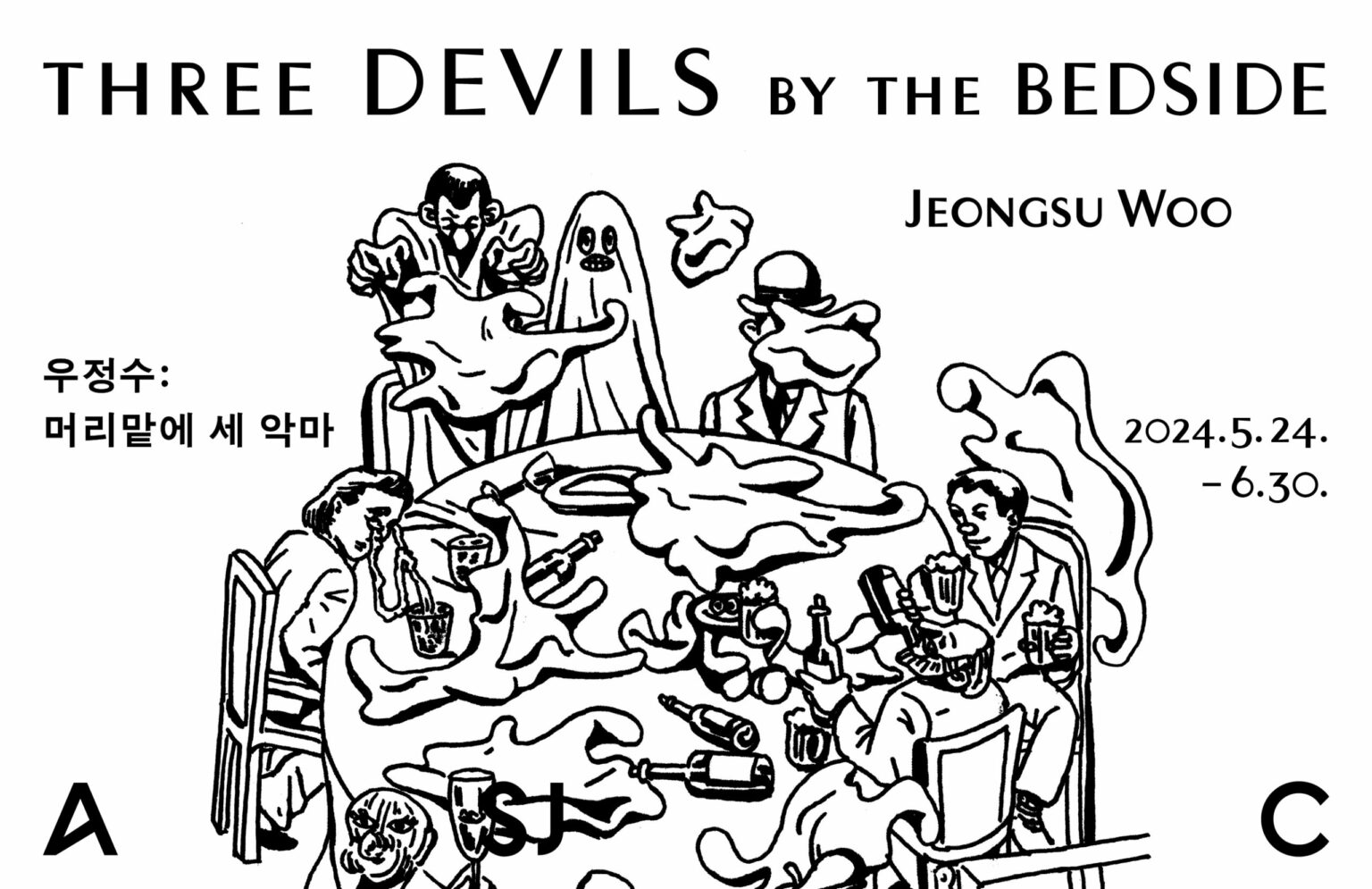

The third solo exhibition of

Jeongsu Woo titled 《Flaneur Note》 is an opportunity to meet about 170 drawings and a book of 8 small

themes that compiled the drawings―all of which records

the inside of the world that he has observed so far with interest and concern,

human nature and its limitations he witnessed there, and the traces of

psychological distresses about his role as an individual and painter. Jeongsu

Woo boldly skips the usual sketching process for full-scale painting and

directly draws shapes on the paper with a brush. At first glance this may seem

easy, but if you understand that paper and ink are sensitive materials in their

nature that do not tolerate even a single mistake, the meaning of the pen

drawings we see in this exhibition becomes clearer. He has repeatedly

introduced various icons in his drawings, and has created his own unique style

by putting them again in various situations to create diversified narrative

structures. Perhaps because he has thought a lot and gone through the process

of expressing his thought several times by drawing repeatedly, the brushwork

itself without hesitation gives strength to the figure in his picture.

More fundamentally, the

proficiency of this technique comes from the artist’s gaze and attitude toward the object. Just like the meaning of the

word ‘Flaneur’, he belongs to

the group called society of today and yet tries not to lose his independent

gaze and attitude as an individual. While completing the book that compiled the

drawings displayed in the exhibition, he quietly watched the society that had

changed over the past decade, with the eyes of an observer. And he put what he

saw into the caricatured figures of humans, animals and grotesque landscapes:

big and small events and accidents in society, actions and movements that

conform to or oppose the solid and strong social systems, as well as the

moments when human beliefs and distrust operate. While using black ink to draw

this with a fast stroke, he does not miss the delicate representation. At the

heart of this is the long training in thinking he has gone through with book

reading. He read books of diverse genres ranging from stories about myths and folk

tales, to biographies of heroes and great men, to philosophical books of

thinkers, and began to observe the ways in which the system of the real world

is constructed and operated and the human life and nature that interact within

the system. In the process, the ‘belief’ that a large amount of knowledge and information produced and

consumed toward the truth will move people's minds and change the reality exist

side by side with the ‘doubt’

that it is difficult to change the reality because of the unpredictability of

the system caused by human avarice and the various variables in society. In the

meantime, the artist naturally took great pains over what kind of attitude he

would take as an individual and a painter in a society. The results were the

first solo exhibition titled 《The Paintings of Villain》 in 2015 and the second solo in 2016, titled 《The Grave of Books》.

The artist has doubted the

situations in which absurd things in reality are justified and construct a

society in a plausible way, and has projected himself onto the figure of the

artist who endlessly produces the images of man against the absurd reality (The

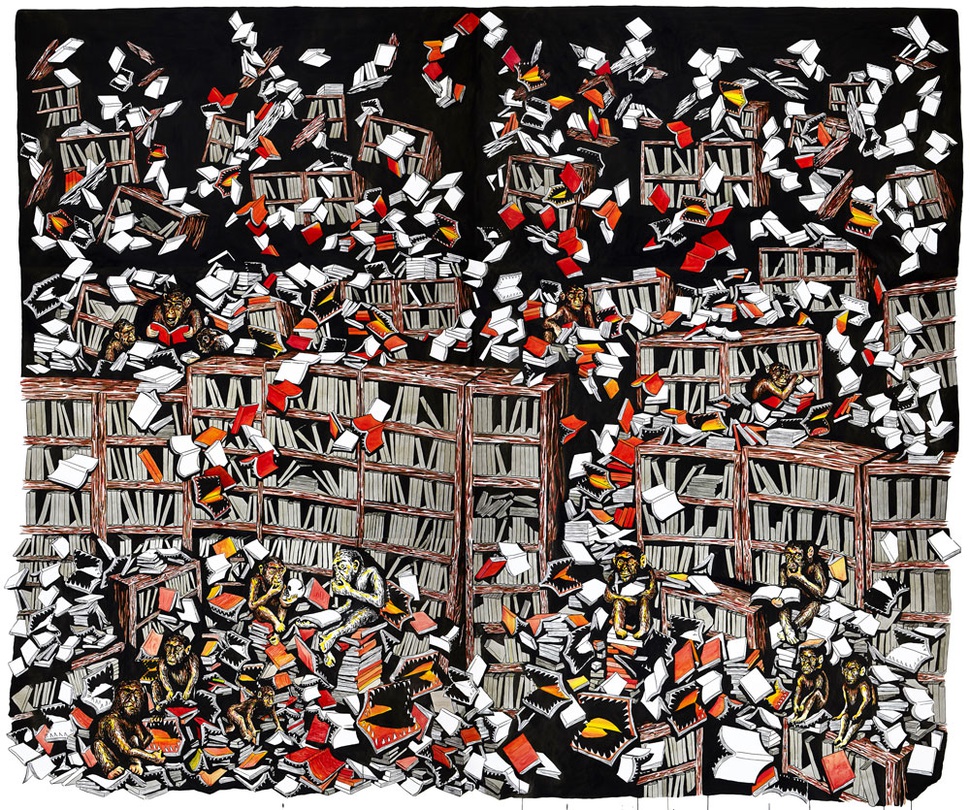

Paintings of Villain); sometimes has expressed the skeptical view that the

endless desire of man for knowledge and civilized way of life may not save this

world (The Grave of Books). Looking at his work over the years, we find that he

starts from expressing in a scathing and outright language his anger he feels

when he witnesses the reality armed with overwhelmingly powerful systems, and

observes how human beings live without seeing the limitations as finite beings,

overburdened by desires and emotions; and he finally scoffs at this by

projecting it onto a wild society or a wrecked civilization. What is important

throughout this process is that he never forgets that it is a major challenge

for his painting to always reflect on his life as a painter. Not only the

chapter entitled ‘Lousy Painter’ in the book displayed, but other chapters also have self-portraits

of the artist. They always have metaphoric representation of the painter’s attitude toward the world as well as his contemplation of the

existence of an artist in society. Through the act of ‘painting’, the painter is forced to perform his role, but he also satisfies

his personal desires through the act. When ‘flaneur’ is defined as a two-faceted being that dwells in the crowd or a

group in society, but at the same time maintains his own perspective at an

objective distance from it, it seems that in Jeongsu Woo’s painting, the ambivalent gaze of such a flaneur is effective both

for the world and for the painter himself.

This self-critical and

self-reflective attitude as a painter not only appears directly in the subject

matter of the painting but also sometimes makes small changes to the way he

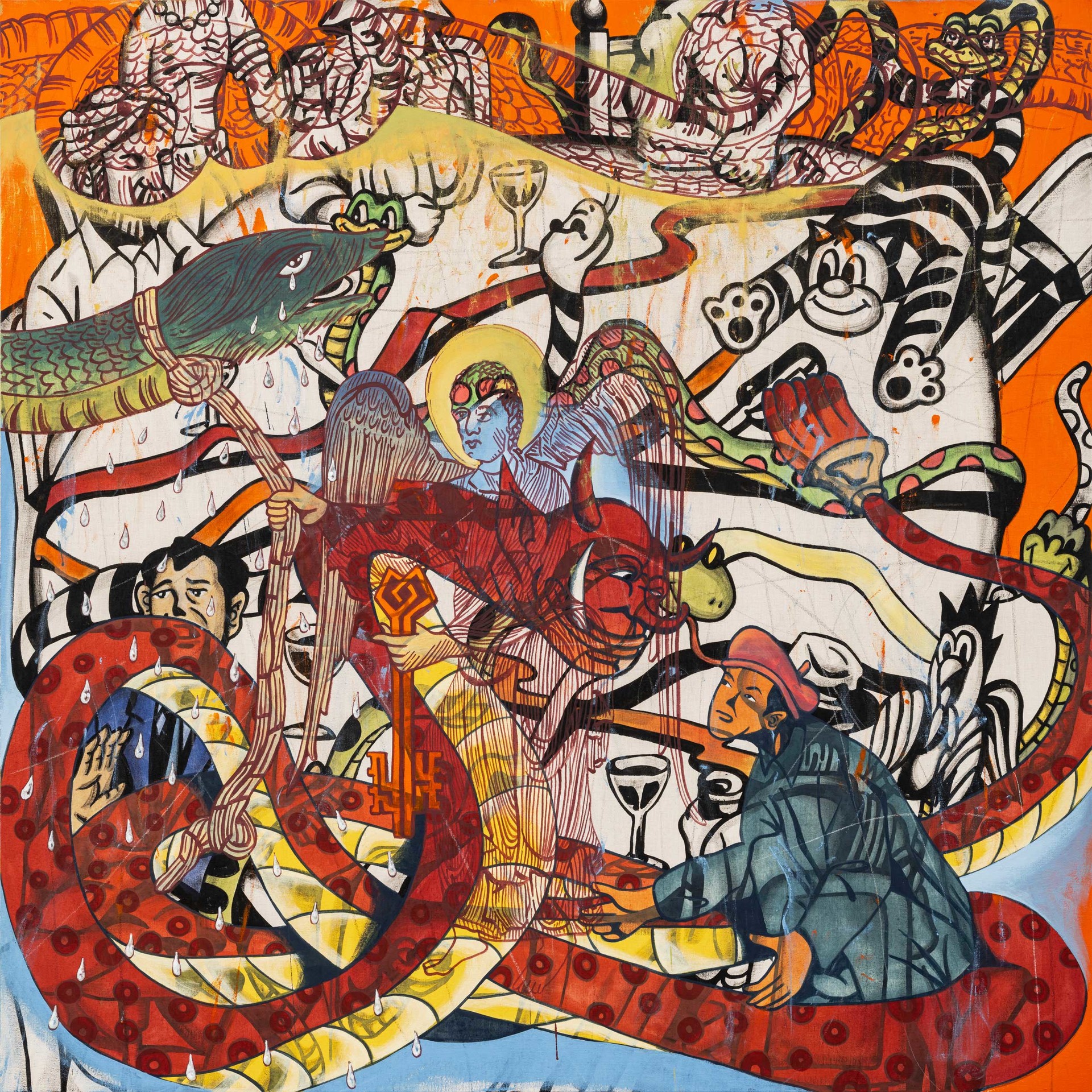

organizes the canvas that he has adhered to in his work so far. In Uroboros

# 1 (2017), the painter has presented the uroboros, an ancient

mythical symbol depicting a serpent eating its own tail, in its complete form

as an archetype. Moving a step further from there, he begins to boldly bring in

the conditions of completely different contexts while deconstructing and

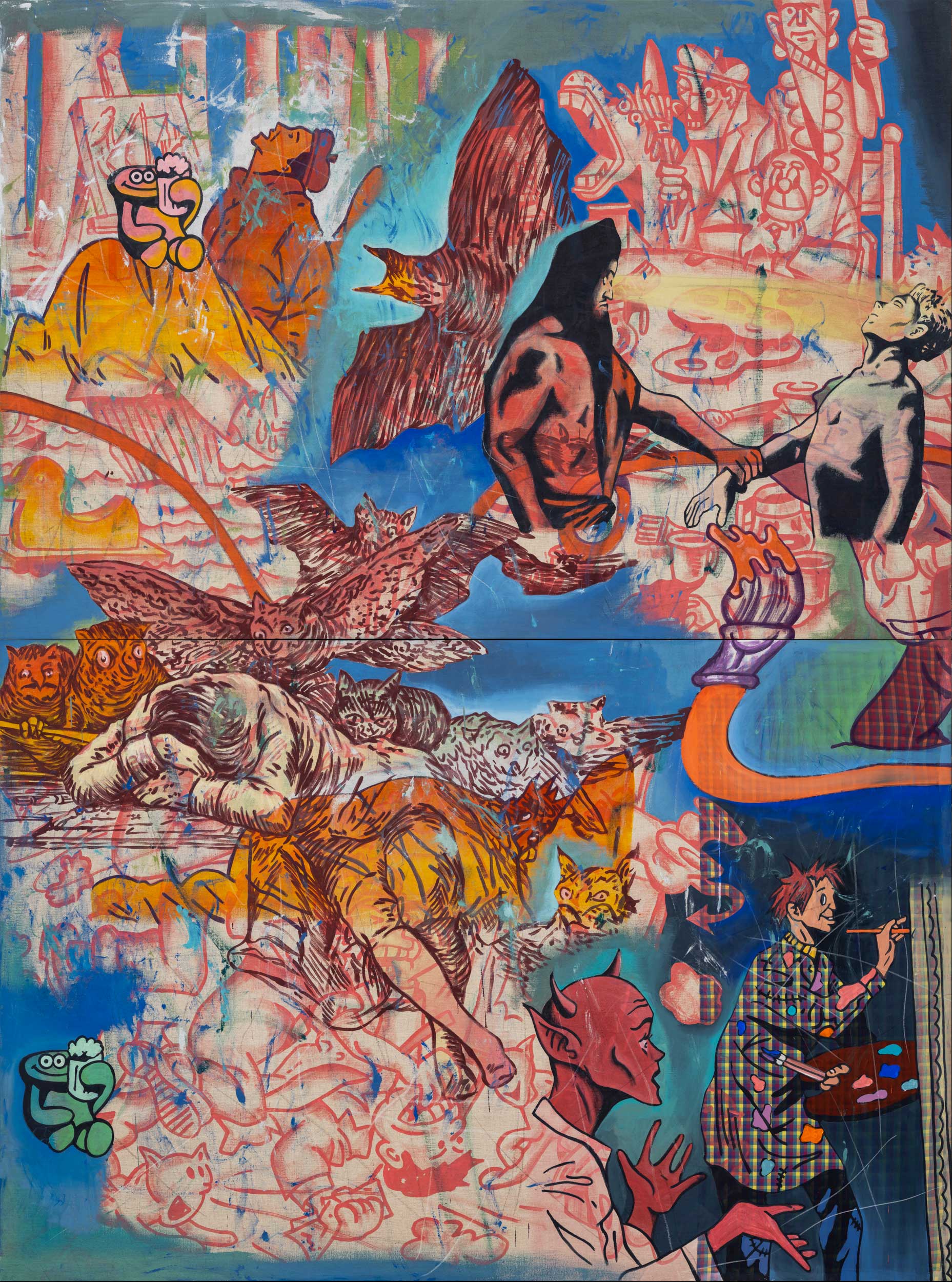

denying the wholeness and totality of the circular structure of the archetype. Uroboros

# 2 (2017), which constitutes another aspect of the exhibition, is

out of the perfect circular structure, and its body is cut off as if it were a

lost puzzle piece, and its surroundings are filled with religious icons

representing unpredictable natural energy and the transcendental world, and the

symbols of human desires to go against nature and of the cynical look at all of

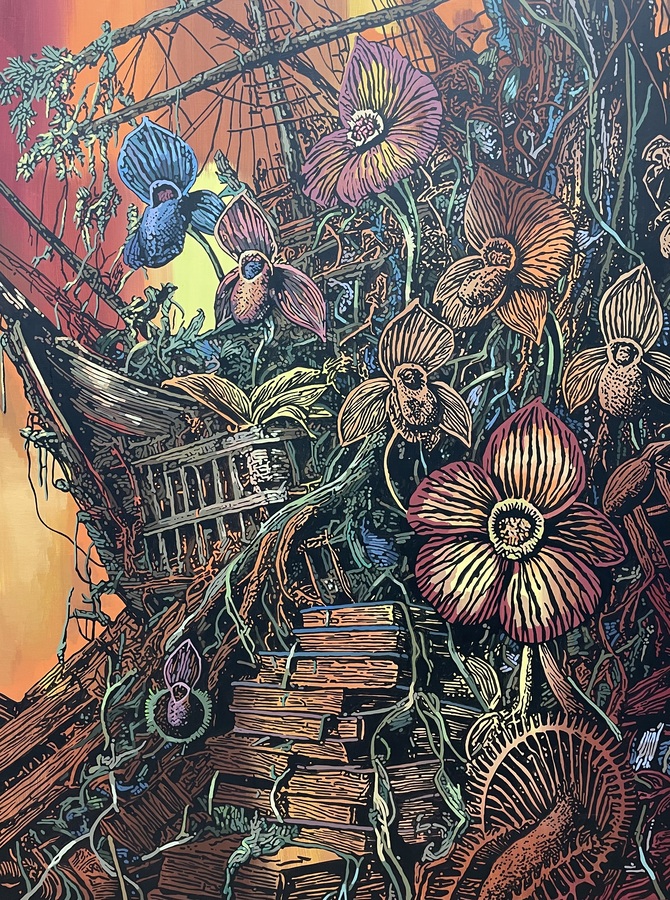

this. The graceful smile of the Virgin Mary spreads beneath the fierce force of

the uroboros threatening to devour, and flowers bloom beautifully even in the

ravages of nature. This is the point that reminds us of the huge circular

structure in contrasting terms, which has been preserved/kept while the

paintings born out of the artist’s fingertips in the paintings of 《The

Paintings of Villain》 turned into masks for the

painter, or Task of Narrative (2016), a work representing

the ‘The Grave of Books’ series, put together the symbols of civilization

drifting in the whole space as if revolving there.

In addition, the technique made

possible by changing the medium from paper to wood panel becomes an element to

underscore this cycle. The technique, by which images were drawn on the paper

and one layer was horizontally expanded, provides the possibility of a new

interpretation in the recent works that make use of wood panels and the shading

of Chinese ink. The method of erasing or moving the first drawn images and

stacking up the layers of images thinly to reveal the relationship between the

images forms a more complex multi-layered structure. The composition segmented

by several wooden panels does not focus on the connectivity between images;

rather, it creates a situation in which the meanings of the individual picture

planes meet by chance and collide with each other horizontally and vertically,

which allows the intervention for an active appreciation and interpretation. If

previous works like Task of Narrative clearly presented the

artist’s view of the object through a complete circular

structure and solid composition created by symbolic images, Uroboros #

2 brings in the viewer’s interpretation and

experience of the object in the appreciation of the work due to the versatile

quality of the technique and composition.

To be sure, this feature has

something to do with the loose connection between the eight different

compositions in the book on display. Each of the chapters, entitled ‘The Heavy Tree’, ‘The

Crown of Fools’, ‘Strange Tales’, ‘The Grave of Books’, ‘To Be the Oriental’, ‘The Face of Ghost’, ‘Lousy Painter’,

and ‘Strolling’, is a kind of

confession in image, which metaphorically captures the traces of existential

concerns he was grappling with not to lose the role of an individual, painter,

and flaneur in the chaotic social reality. Hence, the drawings that make up

each chapter have long been archetypes of thoughts and expressions of objects,

and have also played their role as a pivot around which the overall narrative

revolves when they come out for exhibition.

The artist continues to draw

paintings as a flaneur living in in a society where the brutality of violence

and madness and at the same time the sacredness of salvation and sacrifice

exist side by side. Through 《The Grave of

Books》, he has already dealt with the endless desires

and emotions of human beings toward the reality, but the traces of the time and

agonies he had are ready to talk to the audience in the form of a book full of

pictures. As we can perceive through his gaze at the world, humans are probably

living for a fleeting moment that is just a small dot in the flow of eternal

time. But to the flaneur, who is not afraid of getting lost in the middle of

his stroll , the world must be an uncharted territory where there are plenty of

things that are yet to be discovered, as well as innumerable choices waiting

for him to make his way.