Can painting contain narrative? Reflecting on the long history of

painting striving for its own medium-specificity in confrontation with

literature, this question seems not only difficult but even regressive.

Painting has long been expected to express something other than

narrative—refusing to become a mere tool of literature capturing only single

moments—and has developed by systematically excluding narrative from within

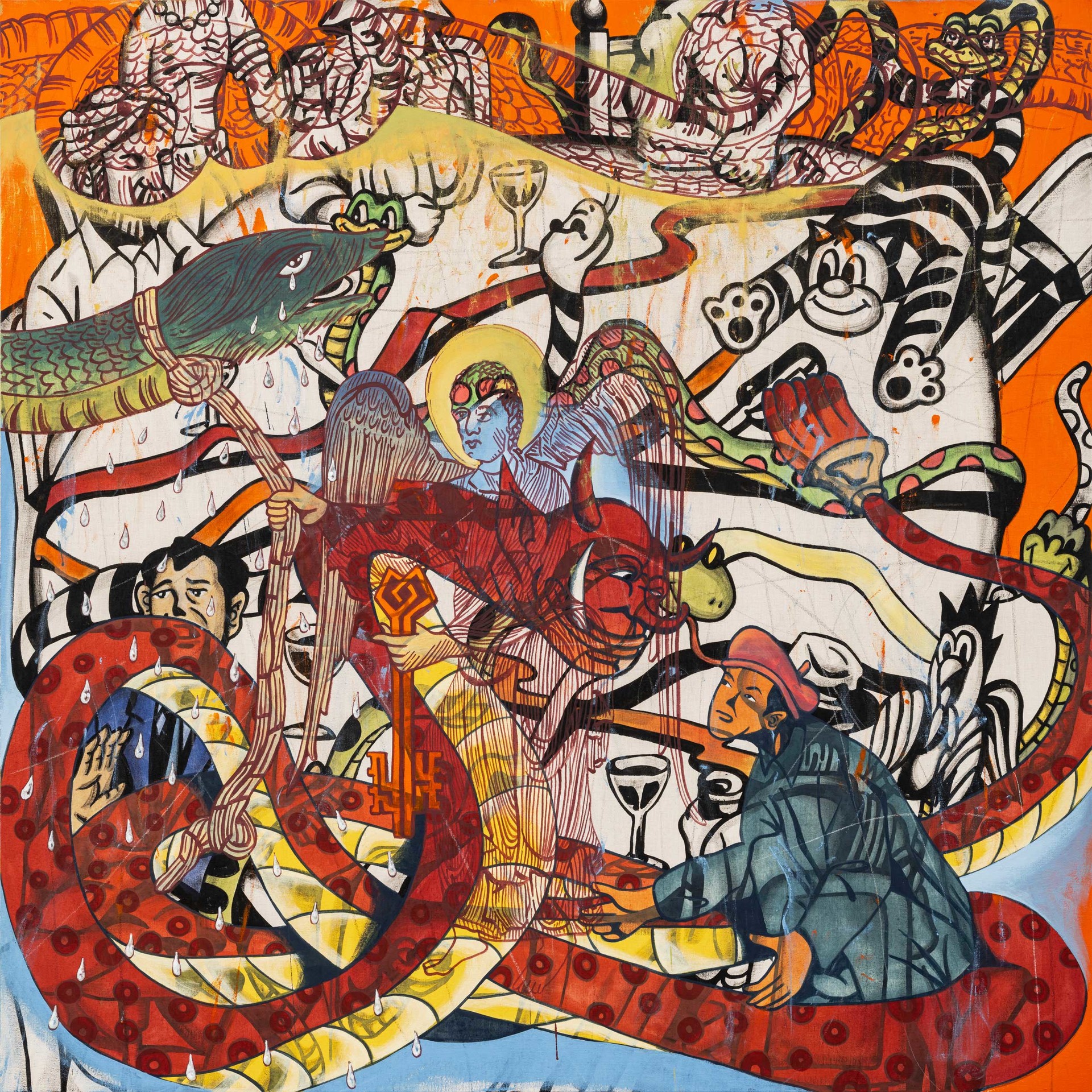

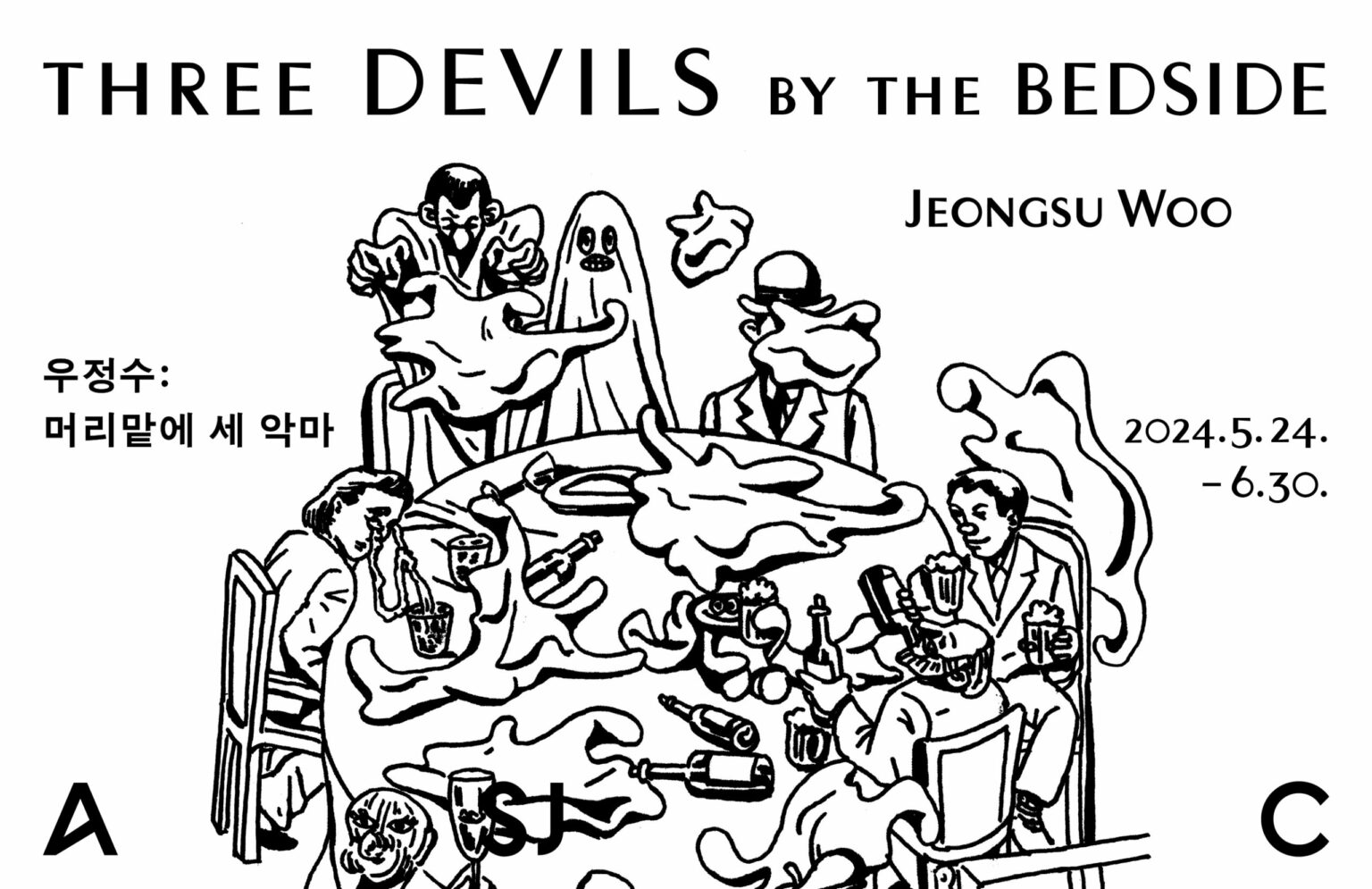

itself. Yet, contrary to this historical tendency, Jeongsu Woo is thoroughly

committed to engaging narrative through images. He continues storytelling

without restriction in theme or genre, and indeed demonstrates that painting—an

image on a flat surface—can convey deeper and more significant stories in its

own language. A duel between two figures governed by the logic of “an eye for

an eye,” the smileman who never loses his grin in battle, the man searching for

something on a small boat—all of these borrow from other narratives, but within

Woo’s paintings, they transform into new stories, stories of images.

From Linear Narrative to Narrative of Gaps

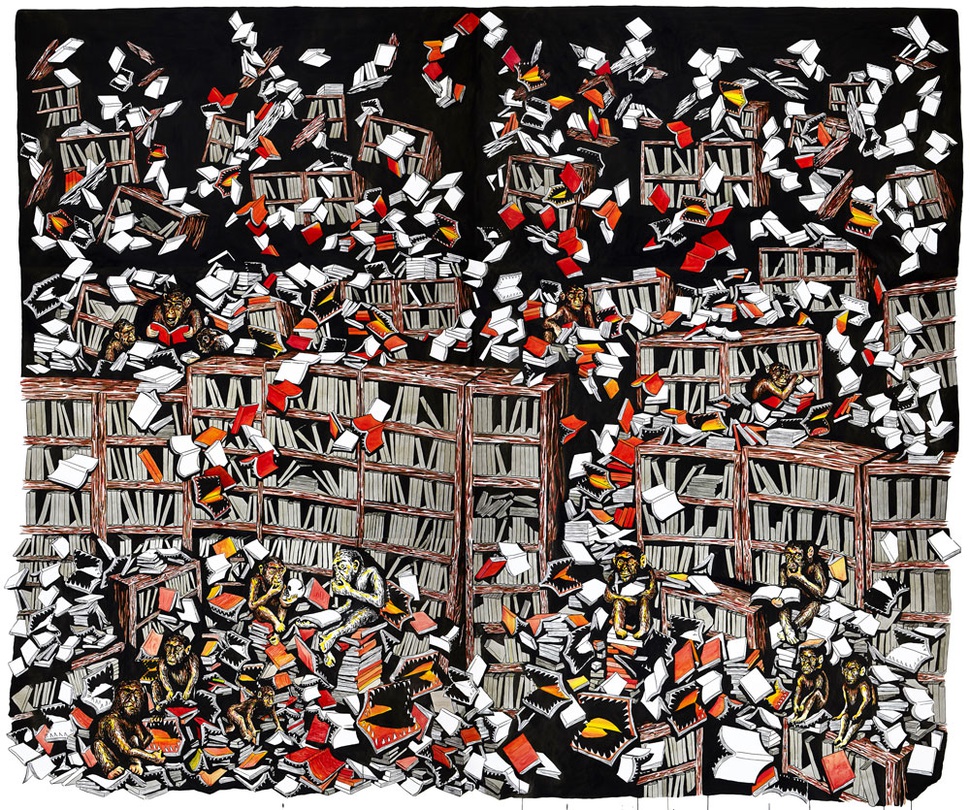

For quite some time, Jeongsu Woo worked primarily in

black-and-white drawings, minimizing the use of color. His bold, calligraphic

strokes on paper clearly revealed variations in line thickness and shading,

guiding the viewer’s eye toward the figuration. By excluding color, which might

disperse the viewer’s attention, he allowed the viewer to focus on form and the

narrative it conveys. These decisive, singular strokes mirrored the linear

progression of stories moving from beginning to end. Resembling woodcut

illustrations from 17th-century books, these drawings seemed to insist that

narrative had always been integral to painting—that storytelling wasn’t solely

the domain of textual language. As if to challenge modern assumptions that

painting cannot contain narrative, Woo’s images opened an infinite world of

stories.

However, in recent years, Woo’s paintings have undergone a

transformation. While they still hold narratives, the way they do so has

changed. The 2018 work Calm the Storm begins with the

biblical story of Jesus calming the storm. The painting captures the climactic

moment—waves crashing upon the sea—but the notable aspect of this work is not

the clearly defined figuration. Composed of multiple large canvases joined

together, the work features fragments scattered like shards of narrative.

Coexisting on the canvas are elements that clearly indicate a story, elements

disconnected from any narrative, and blank areas akin to the dark fade-outs

between acts. Figuration detaches from original context, and as narrative gaps

emerge, images are liberated. If previous works strove to faithfully represent

stories, here the paintings begin to transcend narrative altogether—dealing

with what stories cannot contain, what cannot be filled by language.

Despite this leap, Woo’s paintings didn’t yet change

drastically—they still primarily relied on black-and-white line work to compose

figures and blanks. But soon afterward, Woo began to incorporate color,

producing visually distinct images. In the ‘Protagonist’ series, the central

image is a boat navigating rough waters. This imagery evokes countless

journey-centered narratives, from Homer’s Odyssey to Moby Dick.

Rendered in black-and-white linework, the boat and sea are then overlaid with a

single tone—red, blue, or green dominates each canvas. In Protagonist–vermillion

(2018), as the title suggests, the painting’s base is a deep reddish-orange.

With an overlay of blue atop the vermillion, color constructs an atmosphere.

The ship’s precarious struggle against the waves is heightened through this

tone, implying both the before and after of its story. In this way, Woo expands

beyond black-and-white linework—color itself begins to carry narrative weight.

Images that Weave Narrative

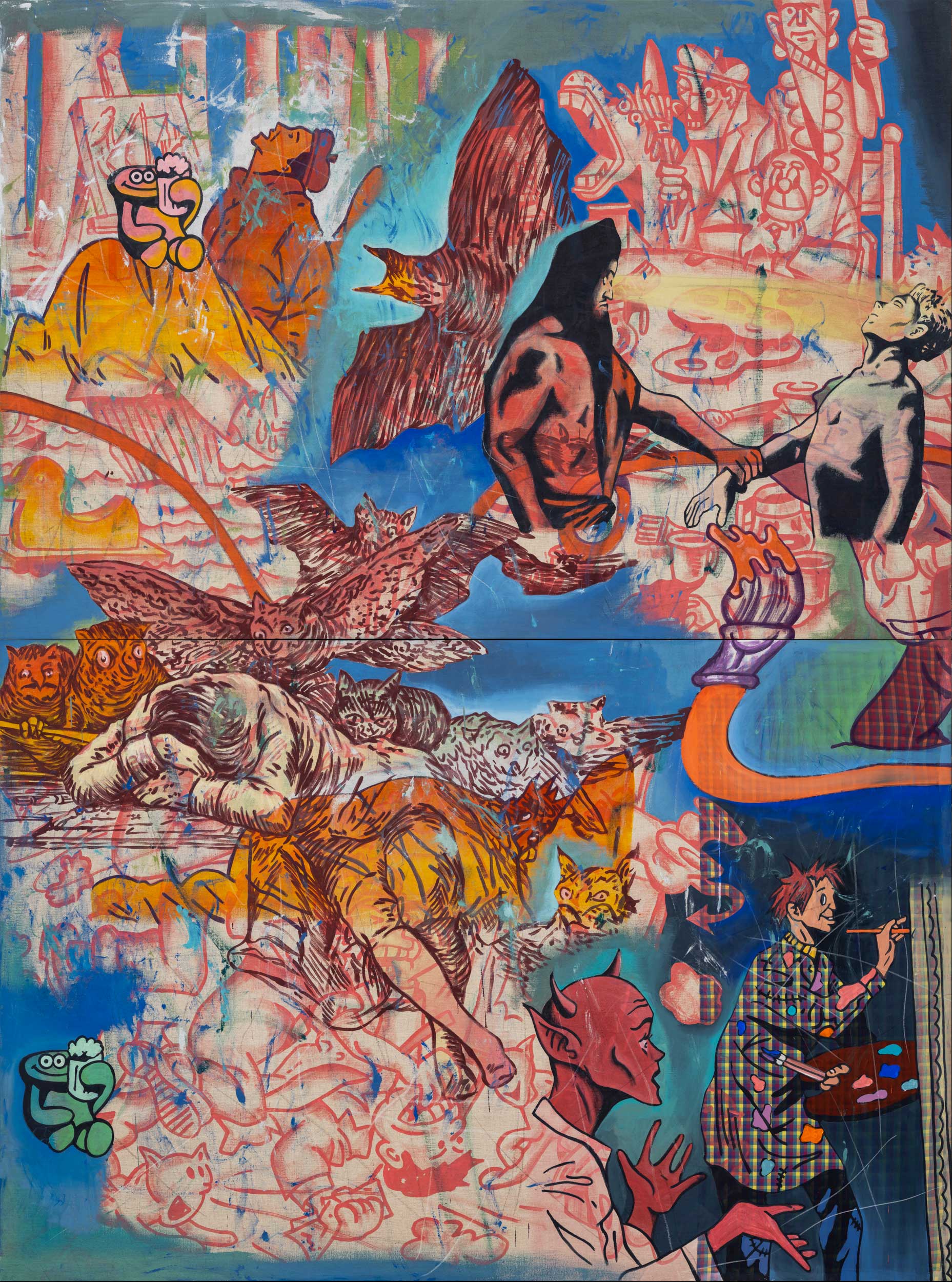

After the ‘Protagonist’ series, Woo increasingly embraced color.

Viewers realized how mistaken they had been in thinking he excelled only in

monochrome linework. He used color boldly and freely. He did not use red merely

to depict a rose more accurately. Color often bleeds outside the outlines,

defying both conceptual and naturalistic color schemes. A single tone becomes a

field that overtakes the subject. Thus, color in Woo’s paintings is not for

descriptive precision but for conveying what form alone cannot.

Works after 2019 clearly display this shift. Large canvases are

filled with expansive color fields, sometimes resembling wallpaper patterns.

Within the gaps of these ornate patterns reside the figures—a ship on waves,

two men practicing martial arts, a woman climbing out of a window, a speeding

car. These narrative-laden figures exist tucked between patterns like

interruptions. This feature becomes more pronounced in Woo’s large-scale works.

Though the canvas size has increased, the scale of the figures remains small.

Much of the space is dominated by color and pattern. As the relative size of

the figures does not scale with the canvas, the density of narrative gives way

to more blankness. The texture of the pattern becomes more pronounced, and the

figure's presence is further reduced. No longer taking center stage, the

figures become part of the overall landscape.

By introducing color, Woo began to layer multiple narratives on

the canvas. His earlier technique of depicting narrative with lines on paper

suited linear storytelling, but lacked the means to build layers of meaning.

With layered color fields came layered narratives. In Man on the Water

(2019), red brushstrokes pierce through a patterned background, forming a new

space where the ship rests. The layers of patterns and figures intersect,

allowing the stories to overlap. In Brighter Tomorrow (2019),

an area of the canvas appears cut out, within which the figure resides. It’s as

though a hole has been made in an upper layer to reveal what lies beneath.

Through this gap, the story of a sinking ship emerges. Color creates multiple

layers, and figures are scattered across these seams. If his earlier

black-and-white drawings resembled epic poems with a clear narrative arc, these

fragmented, layered stories resemble absurdist dramas that break apart linear

narrative. Thus, unseen, marginalized stories—those excluded from dominant

historical or progressive narratives—begin to coexist on the canvas.

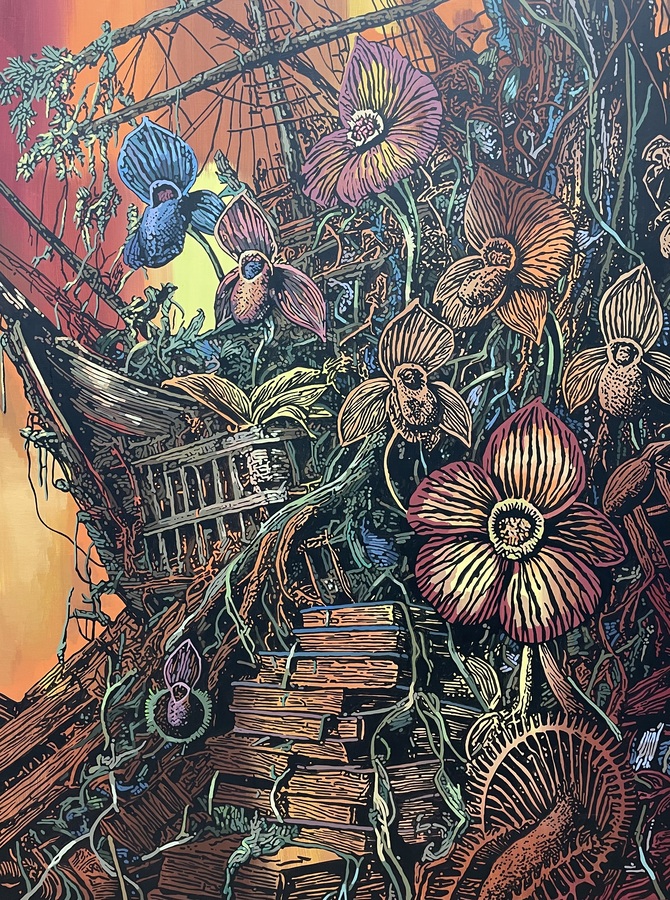

Moreover, the Phineus (2019) series attempts

storytelling without any figuration, consisting solely of decorative Art

Nouveau plant motifs and diagonal argyle patterns. The paintings resemble

wallpaper—composed of patterns but void of specific imagery. At first glance,

these works appear devoid of narrative, yet the title referencing the blind

prophet Phineus from Greek mythology hints at deep layers of meaning. These

stories do not appear as visible images but are conveyed through color,

pattern, and spatial structure. Narrative becomes spatialized, and thus

painting and image unfold storylines in their own language.

The large-scale work Where the Voice Is,

exhibited in this show, fills one entire wall. Volcanic eruptions, a man gazing

into the distance, a man fighting a giant squid, scenes from Greek mythology

repeat alongside roller-inked planes and argyle patterns. These motifs exist

dispersedly, rather than forming a linear sequence. The recurring volcano and

man were borrowed from Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

(1954), but stripped from that context, they take on new roles. Still bearing

the cheerful style of cartoons, the man’s gaze now lands on a blank space,

amplifying a sense of emptiness.

These recurring motifs function like seeds of narrative, subtly

varying and appearing repeatedly—creating narrative through repetition. As

multiples appear, relationships form. Repetition of motifs creates space, and

spatial narrative becomes a structure that reflects broader social and systemic

issues. The repetition of unrelated forms, lacking logical causality, mirrors a

society governed not by reason but by disorder and absurdity. The loss of

social voice manifests not only in hollow figures but also through the

structure of form itself.

Thus, in Jeongsu Woo’s work, narrative is not merely repeated

through images—it is newly woven. His images are not mechanical translations of

text-based narratives. In Woo’s paintings, stories are rewritten through a new

visual grammar—through line and surface, form and pattern. These reconstructed

stories are not linear narratives rushing toward resolution, but dispersed

storylines with no clear beginning or end. They open up a world of multiple

possibilities.

Although still a small part of his practice, Woo has recently

begun exploring different media, including glass drawings and fabric works.

Ultimately, this reveals that what matters to him is not a specific

medium—paper, canvas, ink, or acrylic—but the act of weaving narrative through

images. Those who truly love stories are not confined by genre. From genre

fiction to literary novels, from fiction to non-fiction—when story is present,

theme, length, nation, or gender do not matter. Jeongsu Woo is someone who

truly loves stories. From Greek mythology to DC Comics, he eagerly absorbs any

good tale. He now seeks to weave more expansive stories—not images that simply

illustrate a narrative, but images that actively recompose narrative. Though

the way he contains stories may change, his desire to tell them remains

constant. His voyage in search of better stories and better visual languages is

unending.