Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Her works are exhibited in various solo

exhibitions, including 《My public affairs》(2013, Space Mass, Seoul),

《Mild depressive episode》(2013,

Corner Art Space, Seoul), 《Our little gender stories》(2014, Space Mass, Seoul), 《Miss Lee and

Mrs. Kim》(2018, Art Space No, Seoul), 《Mrs. Jellyby's magnifying glass》(2019, PLACEMAK

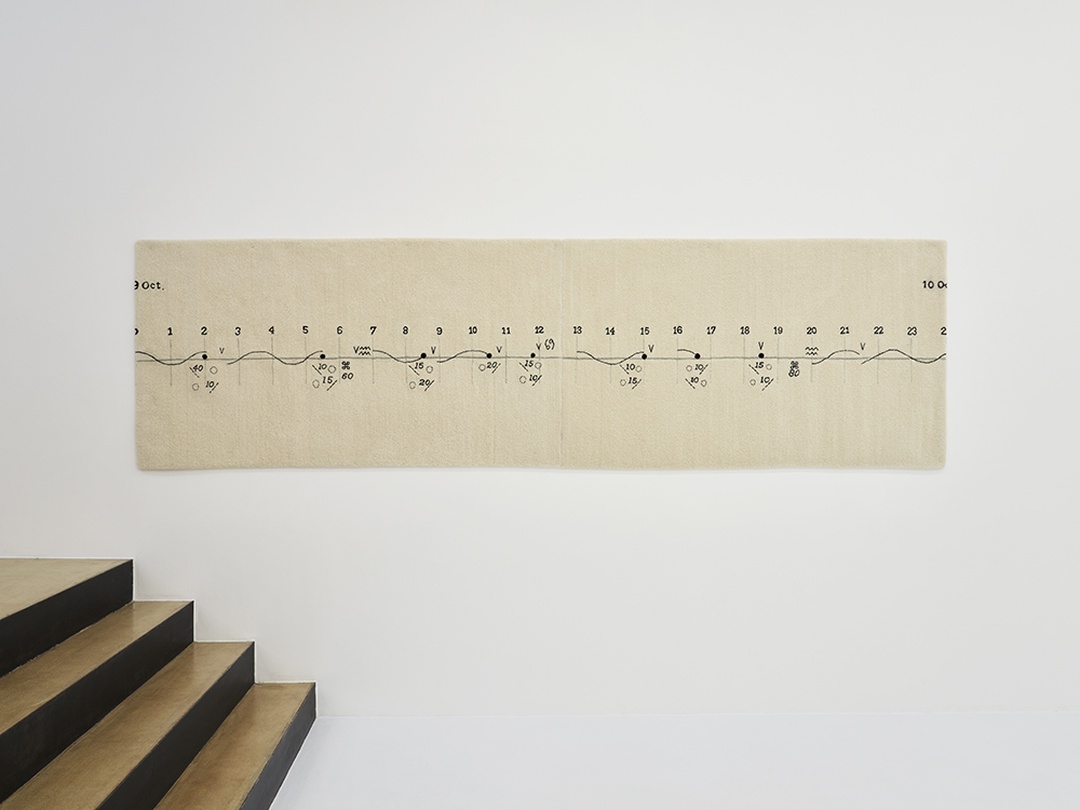

LASER, Seoul), 《Mrs. Jellybee's Magnifying Glass》(2019, PLACEMAK LASE, Seoul), 《Five Seasons》(2020, Seoullo Media Canvas), 《Cotton Era》(2020, Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul), 《Cadenza》(2024, SONGEUN), among others.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Youngjoo Cho also has participated in

numerous group exhibitions, including 《BOUNDARY AND CHANGE》(2002,

Korea-Japan Exchange Workshop and Exhibition, Nakatsue, Japan), 《Parcour Artistique》(2005, Chateau de Petit

Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France), 《Made in Asia, The

5th International Contemporary Art Festival 'Nuit Blanche'》(2006, Le Divan du Monde, Paris, France), 《Splendid

Isolation-Goldrausch 2009》(2009, Kunstraum

Kreuzberg/Betanien, Berlin, Germany), 《Rebus New York

City》(2012, Emily Harvey Foundation, New York, U.S.A.),

《When Cattitudes Become Form》(2014,

Gallery de l'Angle, Paris, France), 《A Moist Lunch by

the Watery Madames: Artists' Lunch Box》(2015, Seoul

Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea), 《Video Portrait》(2017, Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, South Korea), 《The Arrival of New Women》(2018, National

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, South Korea), 《Re: International Exchange Exhibition of Cultural Spaces using

Abandoned Industrial Properties》(2018, F1963, Busan,

South Korea), 《NaNa Land》(2019,

Savina Museum, Seoul, South Korea), 《Promenade Run》(2019, Art Space EMU, Seoul, South Korea), 《Carpenter’s

Scene》(2019, Insa Art Space, Seoul, South Korea), 《Focus On X OVNI: Objectif Video Nice》(2019,

Nice, France), 《Marginalized Histories of Korean Women》(2019, Ridderhof Martin Gallery, University of Mary Washington,

Virginia, U.S.A.), 《Un-wall》(2019,

Kunstquartier Bethanien, Berlin, Germany), 《Interlude》(2019, Insa Art Space, Seoul, South Korea), 《Merry Mix: The More, The Better》(2022,

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Gwacheon, South Korea), 《Seoul Convergence Art Festival Unfold X ‘Shaping the future’》(2022, S-Factory, Seoul, South Korea), 《Flower

Power》(2023, Videocity x SONGEUN, Tübingen,

Germany, Seoul, South Korea), and 《Orange Sleep》(2023, ONE

AND J. Gallery, Seoul), among others.

Awards (Selected)

In 2020, Cho was selected as the Grand Prize

Winner of the 20th SONGEUN Art Award.

Collections (Selected)

Her works are part of collections at institutions

such as the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Busan Museum

of Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, and the SONGEUN Art and Cultural

Foundation.