siren eun young jung has recalled to the present a rapidly

disappearing Korean traditional theater performance genre that is now nearly

forgotten, sought to pinpoint the genre’s position within the lineage of

contemporary art, and continuously refined her inquiry into the genre to draw

out diverse discussions in artistic, cultural, political, and social contexts.

Beginning in 2008 and progressing over a period of nearly ten years, the artist

initiated and carried out Yeoseong Gukgeuk Project, examining yeoseong

gukgeuk—a genre of Korean opera and musical theatre performed exclusively by

women (both male and female roles) that emerged in the late 1940s and peaked in

popularity as a performance genre in the 1950s post-Korean War period. She

proposes a queer interpretation of the genre via a gender politics that

embraces not only the “on-stage” of yeoseong gukgeuk but also the “off-stage”

of the performers’ daily lives by examining yeoseong gukgeuk’s agents, i.e.,

its performers (specifically, those who perform the male roles) and its

audiences.

As an initial matter, I recommend siren eun young jung for Korea

Artist Prize 2018 because she is an artist whose practice is sincere and yet

steadfastly practical. Swimming against the unyielding current of the present,

the artist has slowly but steadily breathed new life into the history of

yeoseong gukgeuk and conceived new artistic productions via a seamless

synthesis with contemporary art by immersing herself into the art and lives of

non-subjects that have not been recognized in official histories and by

listening to, documenting, and questioning their stories in the most intimate

of settings. The artist treasured her memories of meeting with elderly yeoseong

gukgeuk performers—from her instant enchantment the first time they met to the

(at times) uncomfortable sentiments that she felt while sharing in their

everyday lives. Initially proceeding by documenting the performers’ voices, the

artist then attempted to go beyond her personal experience and sought to engage

in a re-contextualization of yeoseong gukgeuk. At first, her works comprised

scenes of the performers’ makeup and rehearsal sessions and interviews with the

performers. In this manner, she created a kind of “yeoseong gukgeuk archive,”

playing the role of a documentary artist while fastidiously maintaining a

proper distance from the objects of documentation. She then went on to create

new stages and videos for the yeoseong gukgeuk performers, in the process

experimenting with artistic intervention and aesthetic and artistic

transformation. Throughout these evolving processes and over an extended period

of time, the artist did not strategically target a specific goal, but instead

repeatedly paused to carefully and constantly question herself as to her

reasons for representing yeoseong gukgeuk. Thus, this project was never

intended to have a specific point of completion. Instead, it serves as a record

of the artist’s long journey to find answers amid its incompleteness.

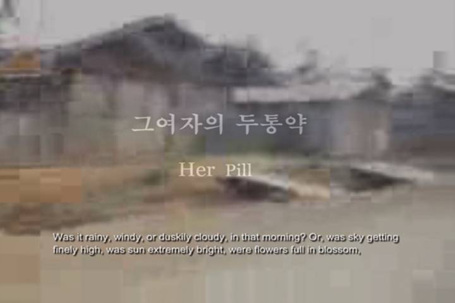

Through Yeoseong Gukgeuk Project siren eun young jung approaches

gender politics from the perspective of unanchored gender. The artist

discovered that the yeoseong gukgeuk performers ultimately “alternated” their

gender and that gender is something that emerged into view at different stages

of their lives, and she recalled this process through oral statements, theory

studies, photographs, video works, and performances. An elderly performer on

stage in (Off) Stage(2012) reflects on her personal

stories about how a female performer with a male role in yeoseong gukgeuk had

to be a man off stage in order to be a dashing man on stage. They not only

practiced acting techniques in order to appear like debonair men, but also

talked, walked, and acted like men in their daily lives in order to train their

bodies and acquire the requisite attitude. Yet, as revealed

in Masterclass(2010, 2012, 2013), which depicts a

protégé’s lesson where the male role is passed down to the younger generation,

the man that yeoseong gukgeuk was trying to realize was exaggerated to such a

degree such that he was nothing like the men in reality, thus twisting the

common perception of gender. In other words, the work presents the masculinity

that the performers were trying to “embody” both on and off stage as a type of

fantasy; nevertheless, it prompts us to reconsider the mindset itself that

acknowledged and accepted such gender characteristics in the first place.

Notably, in the works noted above, the artist prepared stages for yeoseong

gukgeuk performers upon which they could reveal their previously unspoken

stories, but in her lecture performance Gender Bender

Fencers(2014, Arko Art Center; 2017, Haus der Kulturen der Welt), the

artist shifted roles to herself became a performer who put forth discussions of

a new gender that is located outside the precepts of binary gender.

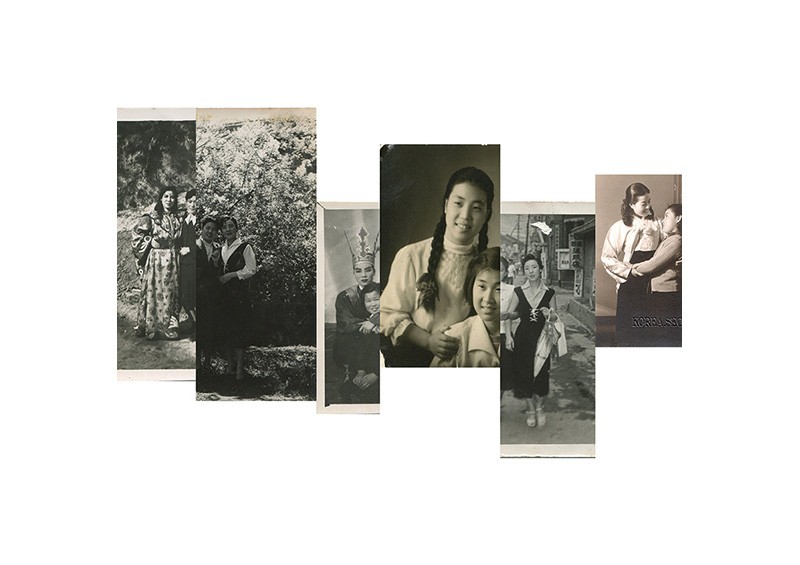

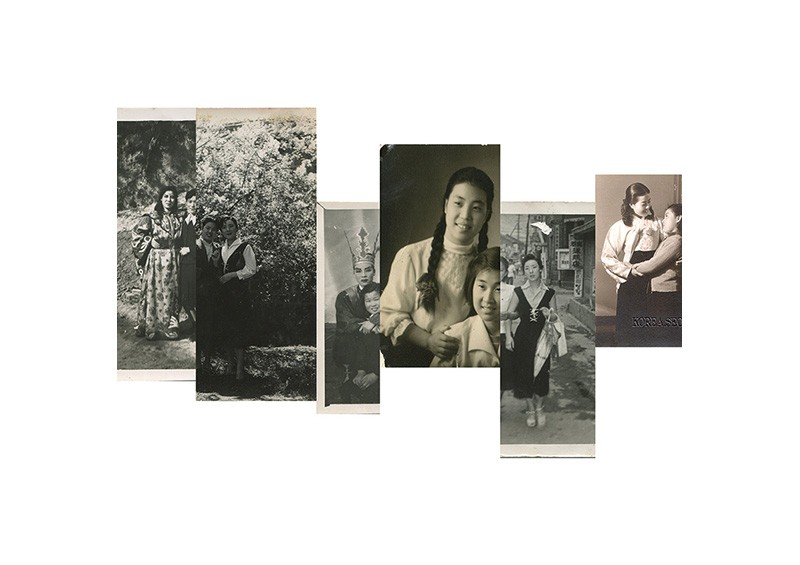

In her solo exhibition 《Trans-Theatre》(2015, Art Space Pool), the

artist took image montages extracted from the archives that she created and

organized them under the title Public yet Private

Archive(2015). Sohyun Ahn, the curator of this exhibition, explains

that in a situation where no definite center is established, the tendency of

the images that the audience reads is revealed simultaneously as being

dependent on certain social customs that are inscribed in people and also as

subverting such customs, and this tendency is a common denominator between

gender formation and archive exhibitions.

At Namsan Arts Center, siren eun young jung

showcased Anomalous Fantasy(2016), which was her first

formal theater-based work and thus signaled a new phase of Yeoseong Gukgeuk

Project. In this work, the artist retraced her initial intent to focus on the

background of yeoseong gukgeuk’s birth and its “gender play,” and pondered

“what is left behind after its decline.” Through the fate of Nam Eun Jin, a

member of the last generation of yeoseong gukgeuk male-role performers, and the

voices of G-Voice, an amateur gay chorus, she attempted to “awake the Dionysian

aesthetics that remain in the unstable lives of those who were not able to

reach a ‘proper’ position in this society.” (Artist’s

Note). Anomalous Fantasy examines the multiple

reasons for yeoseong gukgeuk’s failed history (specifically, its deliberate

exclusion from male-centric modernization, thus becoming the “other”) from a

contemporary perspective and actively confronts today’s nuanced gender

politics.

Approximately one year has passed since I initially wrote this

recommendation letter. I would now like to return to where I left off and share

my thoughts on siren eun young jung’s work Deferred

Theatre(2018), which was presented at the 2018 Korea Art Prize

exhibition at MMCA Seoul. Along with her continuing process over more than ten

years of approaching, observing, and documenting yeoseong gukgeuk and bringing

it into the present, I understand this work’s role as one that compels the

artist to ask herself, time and time again, why she has to undertake Yeoseong

Gukgeuk Project, and specifically why she has to do so at this particular

moment in time. Set in the background of a theatre, jung asks three

performers—a male-role performer from the last generation of yeoseong gukgeuk,

a singer of Korean opera, and a drag king—their opinions about the genres that

they work in, and then intersplices their contrasting answers in a manner that

has the effect of further raising new questions. The performers express their

passion for or captivation by their genres, but their attitudes toward these

genres are divergent and, indeed, at times almost diametrically opposed to one

another.

In particular, as the artist directs pointed questions toward a

yeoseong gukgeuk performer whom she has spent quite a long time with, she seems

to invite a critical introspection about the performer and the artist, as well

as about the exact reason they have undertaken a series of projects to

represent yeoseong gukgeuk. In response to the artist’s questions about how

yeoseong gukgeuk will be able to survive in the future and whether it is

actually worth preserving, male-role performer Nam Eun Jin answers that it may

be possible if done well with a proper flow so that audience members can

empathize with it. However, the artist responds, “I don’t think it would be

possible.”

The performer wishes that, as one of many diverse facets of Korean

traditional culture, the disappearing genre of yeoseong gukgeuk could continue

on. However, by juxtaposing this with the rather cynical attitude of gagok

changja (singer) Park Minhee, who performs traditional Korean gagok within a

new contemporary frame and states matter-of-factly that “gagok has no position

whatsoever” and “it’s really no big deal even when something that was beautiful

in one age disappears,” the artist explicitly reveals the two performers’

contrasting viewpoints on tradition.

This juxtaposition certainly recalls the disparity between one

viewpoint that identifies tradition with history and understands it as fixed,

thus considering it either as something to unconditionally deny or otherwise

defend, and another that understands tradition as a continuum that has been

arrived at through constant evolution.

The scenes also intermix the male-role performer and drag king

Azangman. The artist carefully constructs a discussion about gender politics in

between the male-role performer, who has inherited and practiced exaggerated

gestures and a masculine voice to represent an imaginary masculinity in

traditional yeoseong gukgeuk, and the drag king, who uses her singing on the

stage as a performance platform and thus as a means to liberating her sexual

identity. However, even though the intention of the artist is to inquire about

and discuss tradition and the present as well as gender politics, what these

performers express is not so much a macro perspective on tradition and history

than something more like a confession in which they perform the genres that are

essential for them, and they do so in order to tell stories about life and to

make and sing private and trivial songs. In fact, this overarching confession

resonates more powerfully than any of the interviewees’ individual opinions.

The work then depicts documents and video clips from the yeoseong

gukgeuk archive that the artist has collected and a clip from an interview with

Cho Young Sook, a first-generation yeoseong gukgeuk performer. Finally, the

artist reads excerpts of a historical document from the modern male-centered

gukak field that intentionally denigrated and attacked yeoseong gukgeuk. While

furiously criticizing the activities of all-female troupes, even citing the

proverb “when a hen crows, that family will be ruined,” the document concludes

with an admonition that “male and female changguek performers alike must create

and cultivate their skills, thus endeavoring to establish traditional

changgeuk.” Subsequently, the artist removes the words “male and female” and

“tradition” from the preceding sentence and asks again, “is there any reason

[why yeoseong gukgeuk] should exist?” to which the yeoseong gukgeuk performer

answers, “I wish that what I like would survive, it is a personal wish.”

However, the next scene again displays an article that reveals the fierce

volition of the yeoseong gukgeuk performers who stood up to the male-centered

gukak field.

Deferred Theatre deconstructs issues of

tradition, the present, and gender through interviews with three performers but

only alludes to the possibilities of how to reconstruct them. As the artist

traces back the history of yeoseong gukgeuk and critically examines the

present, she seems to have located a point of synthesis somewhere in between

the passionate affect where the on-stage and daily off-stage lives fused

together among the first generation of yeoseong gukgeuk performers and the

affect embracing the vague dreams of the last generation of male-role

performers.

1. This essay was initially written in 2017 to recommend the

artist siren eun young jung for the Korea Art Prize 2018, and this revised

version incorporates my thoughts on her new work, Deferred

Theatre(2018), which was shown at the Korea Art Prize 2018 exhibition

at MMCA Seoul.

2. Young Wook Lee, Park Chan-kyong, “How to Sit: Tradition and

Art,” 《How to Sit》(Seoul:

Indipress, 2016), 24. In the essay for the exhibition 《How

to Sit》 curated by Young Wook Lee, Lee and Park begin

with the poem “Colossal Roots” (1964) written by poet Kim Soo-Young (1921–1968)

to approach the concept of tradition from multiple different perspectives by

linking examples from Korean contemporary art.