Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Lee Bul held her first solo exhibition at IL Gallery (Seoul,

Korea) in 1988, marking the beginning of her career as an artist. She later

gained international recognition through exhibitions such as 《Projects》(1997, The Museum of Modern Art,

New York, USA) and 《Venice Biennale》(1999, Venice, Italy).

Entering the 2000s, Lee held numerous solo exhibitions at major

global institutions, including 《Life Forever》(2002, New Museum, New York, USA), 《Lee Bul》(2008, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, France),

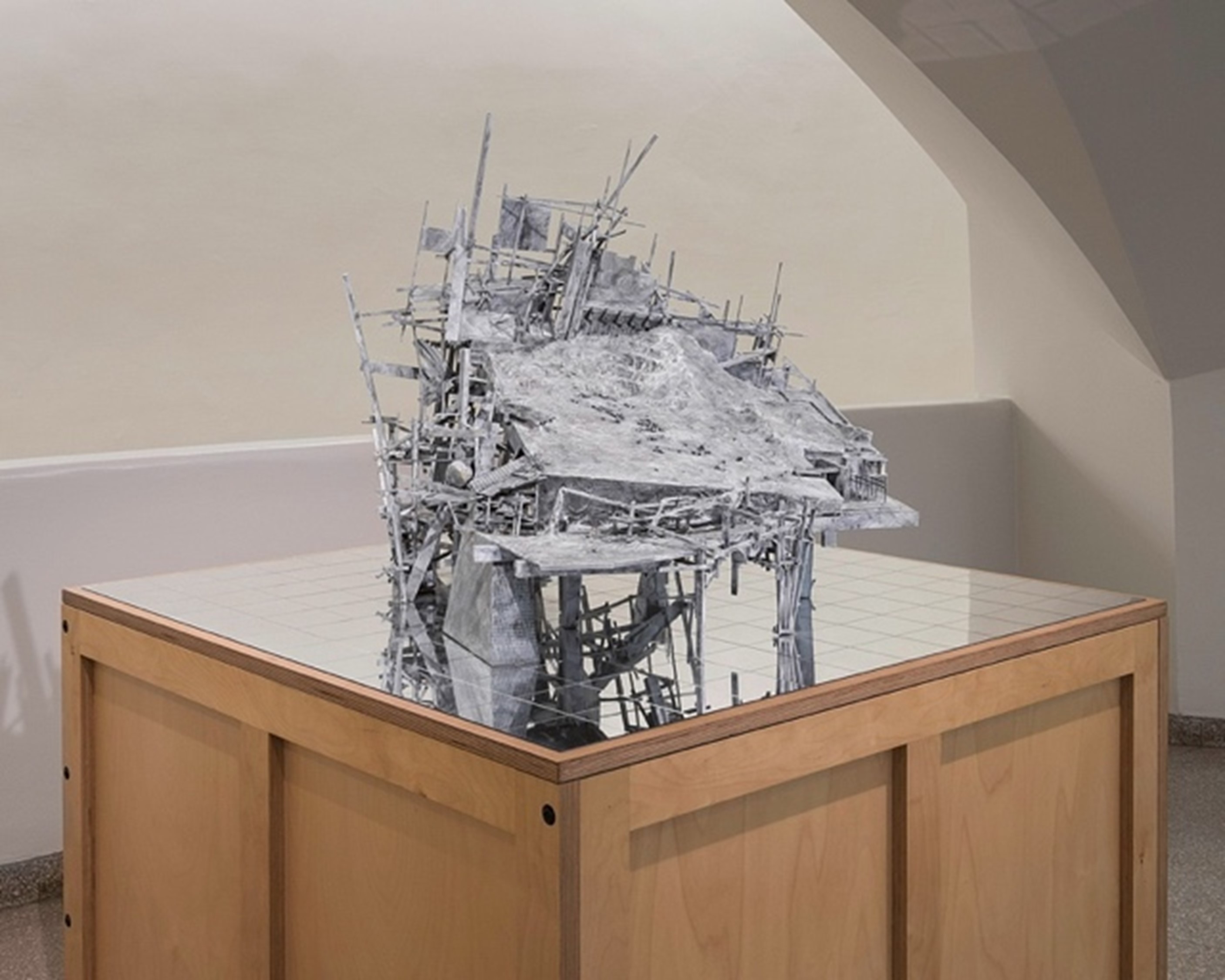

and 《Lee Bul: Crashing》(2018,

Hayward Gallery, London, UK; Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany), solidifying her

position as a leading contemporary artist.

In 2012, she became the first Asian female artist to hold a

large-scale retrospective at Mori Art Museum (Tokyo, Japan) with 《From Me, Belongs to You Only》. In 2024, her

major commission project 《The Genesis Façade

Commission: Lee Bul, Long Tail Halo》 was installed on

the façade of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, USA), further cementing

her international recognition.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Since the 1990s, Lee Bul has participated in numerous prestigious

biennales and group exhibitions, significantly contributing to the

international presence of Korean contemporary art. She garnered attention at

the 《Venice Biennale》 (1999,

Venice, Italy), where she was invited to both the International Exhibition

curated by Harald Szeemann and the Korean Pavilion.

She has also participated in significant exhibitions such as 《Media City Seoul》(2000, Seoul Museum of Art,

Seoul, Korea), 《Transformation》(2010,

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), 《Storylines:

Contemporary Art at the Guggenheim》(2015, Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA), and 《Gwangju

Biennale: Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning》(2021, Gwangju,

Korea).

More recently, her works have been exhibited in 《Dans l’air, les machines volantes》(2023,

Hangar Y, Meudon, France) and 《Supernatural – In the

Same World》(2023, Oulu Museum of Art, Oulu, Finland),

where she presented unique interpretations of technology and human existence.

Awards (Selected)

In 1998, Lee Bul was shortlisted for the Hugo Boss Prize(Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA). In 1999, she received the Special Prize at the Venice Biennale(Venice, Italy). In 2014, she was awarded the Noon Art Prize at the Gwangju Biennale(Gwangju, Korea), and in 2019, she won the Ho-Am Prize for the Arts(Seoul, Korea).

Collections (Selected)

Lee Bul’s works are part of major museum collections, including the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art(Gwacheon, Korea), Leeum Museum of Art(Seoul, Korea), Art Sonje Center(Seoul, Korea), Amorepacific Museum of Art(Seoul, Korea), The Museum of Modern Art(New York, USA), Tate Modern (London, UK), and M+ Museum(Hong Kong).