Individual narratives, group memories

We explore artists’ identities through their works. Various

messages can be observed in the life of a single artist: the problems of an

individual, or of a society, or of a state. While living in Germany for over 20

years, Chan Sook Choi has contemplated the history of human migration, the

scientific and technological devices that enabled movement through space, and

the issues of spiritual migration that accompany physical movement. On a

microscopic level, she has acutely sensed the changes in unfamiliar environments

around her, while exploring on a macroscopic level the history of humanity and

its inevitable migrations as a whole. Using multiple media including video,

performance and installation, she has reflected upon the lives of herself and

of other women like her, while developing a calm and composed voice of her own.

All of Choi’s work starts from situations that can arise in

humanity, history and society, but her perspective begins with highly intimate

human histories. Normally, when art is used to address issues of humanity,

history and society, the private life perspectives of individuals become

inadvertently buried within grand narratives, but Choi’s works stand in

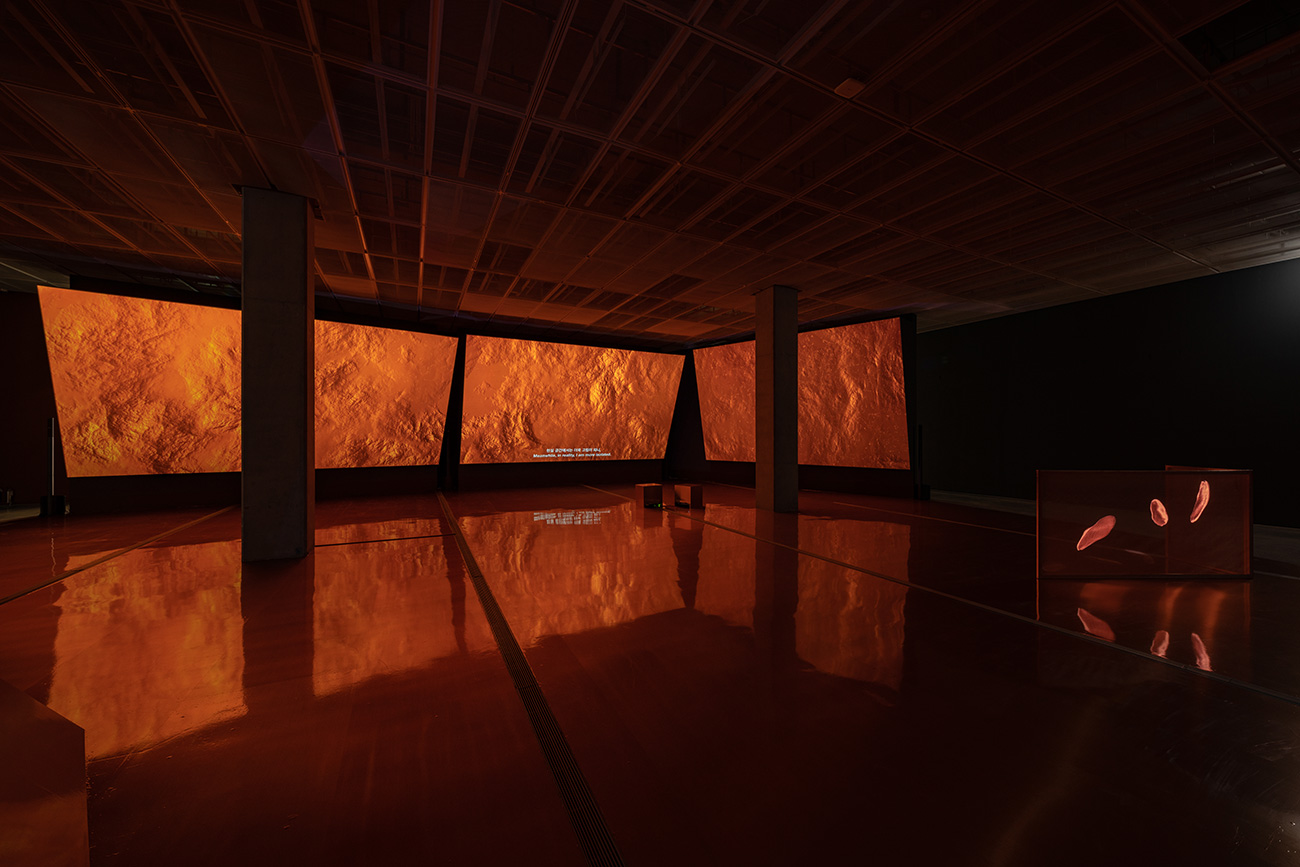

diametric opposition to this rule. A direct example of this is The

Promised Land, in which the exhibition hall is designed with machines

and technology against the background of a company producing vehicles through

beautiful, magnificent automation. The work prompted an awareness of just how

mechanical a space we find ourselves in in contemporary society. But the artist

goes further, also placing devices within the automated system that show videos

of extremely ordinary private lives, awe of God, and stories of ordinary

individuals able to live as protagonists in unfamiliar places. Here, she is

stating that even within automation and technology-oriented perspectives, we

must remember and maintain our human love, our intimate conversations with

those around us, and our private daily lives.

Choi’s works thus relocate the philanthropy and love of humanity

that cannot be produced or handled using automated systems, despite the highly

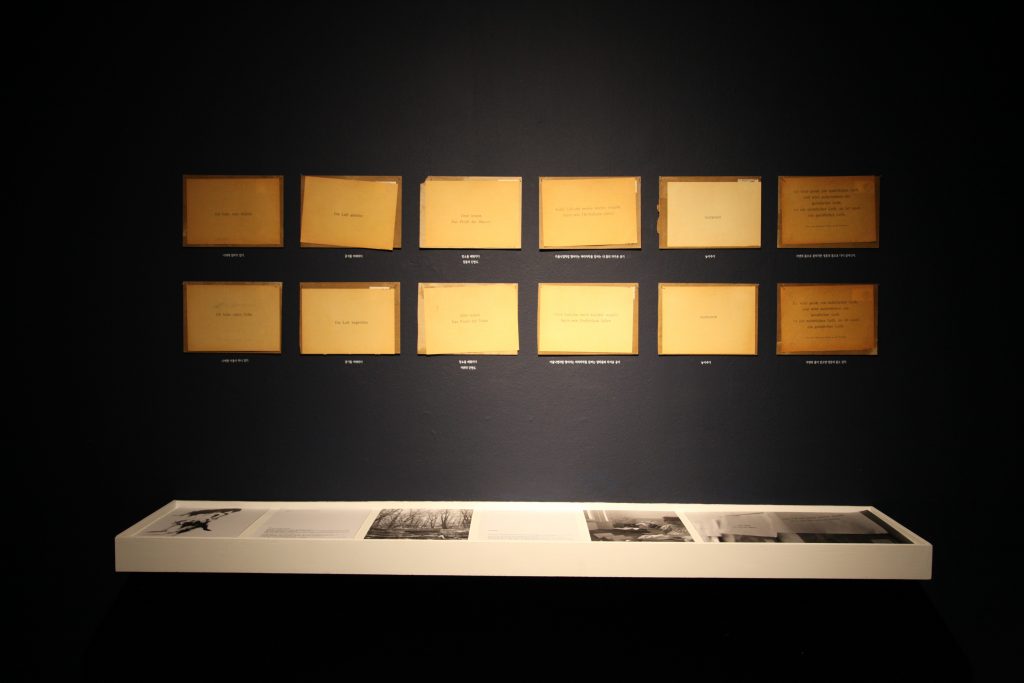

industrialized nature of our society. This line of work continues in FOR

GOTT EN. Conducted during her residency in Leipzig, this work was

created to record how women in their 70s, 80s and 90s narrated their memories

of God, faith and religion. It explored “spiritual migration,” a phenomenon

totally different to that of physical migration (via transportation). If The

Promised Land presented a situation of coexistence between physical and

spiritual migration, FOR GOTT EN shows a more

practical extension of the latter concept. The women who took part in these

interviews had moved from the other cities in Germany to Leipzig.

To the artist, spiritual migration includes issues of

re-transplanting or re-raising and re-organizing memories. Choi created a

dedicated interview space in which to focus solely on issues of God and faith

with the women. The space was produced as a mobile tool. Inspired by the form

of a Korean kiln, it was built as a place for recording special memories while

cut off from the outside.

Choi takes special situations and historical events that must be

directly confronted while standing firmly in the time and space of the present

as the central themes of her work. Using a variety of media, she evokes

problems that were not resolved in the past, or are impossible to resolve.

Summoned once again through her works, these problems are presented using

arguments on a completely different level to the narrative methods of history,

politics and sociology, though they deal with specific periods and events.

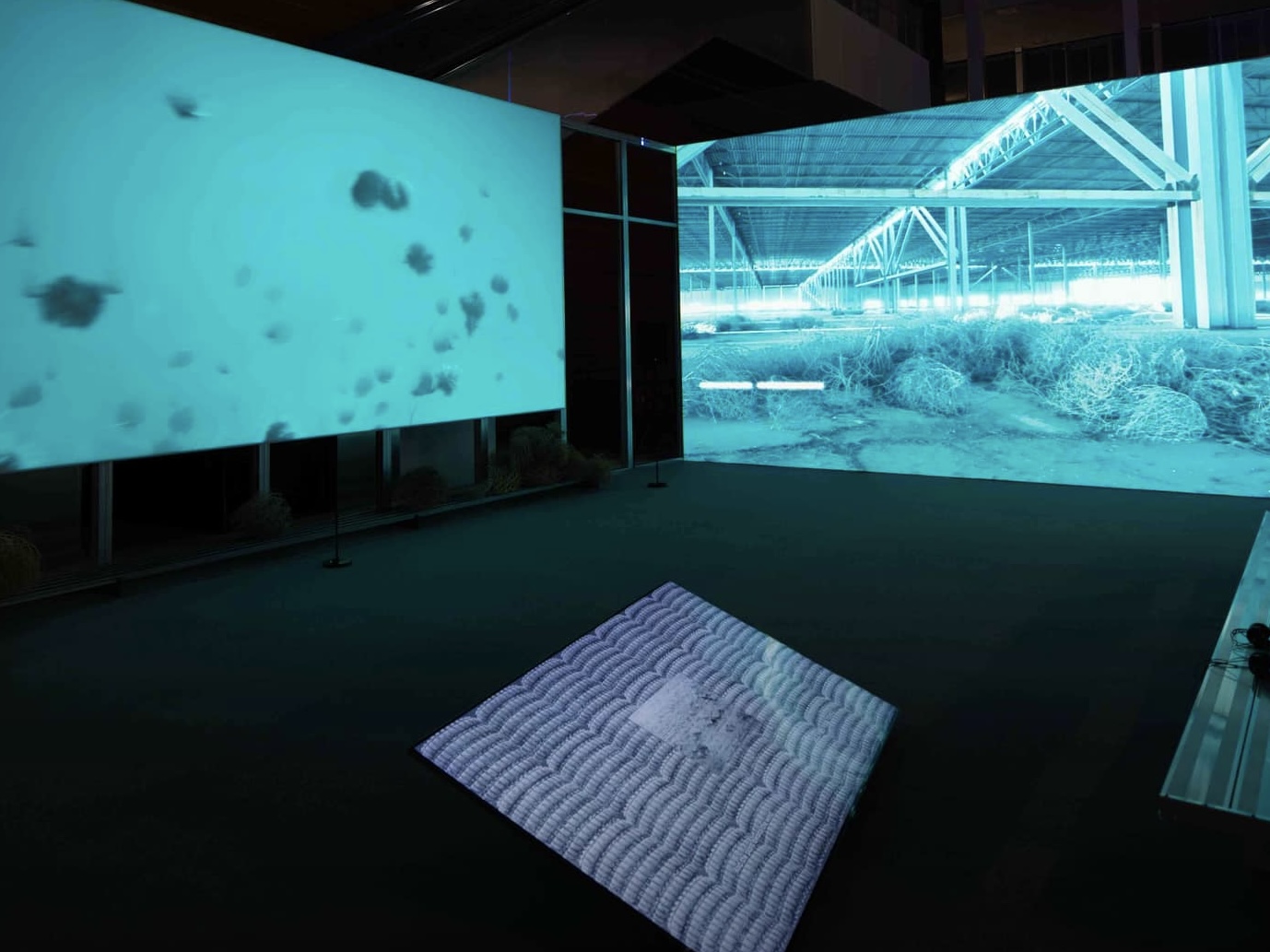

Examples include Yangjiri Archive, produced over

several months living in Minbuk Village, on the border of Korea’s Demilitarized

Zone (DMZ), and Myitkyina, a work on the subject of

comfort women. The themes chosen by the artist for her works—Minbuk Village and

its residents, comfort women, migration—are ones that remain unresolved in

Korean society. In this way, she uses a provocative yet restrained formal

language to express weighty themes from the hidden side of Korean society that

remain unresolved despite their importance.

Choi has devoted herself to two keywords, “migration” and “women,”

with a central focus on Yangjiri Archive. Indeed, the

topics of Minbuk Village and comfort women, in which she has immersed herself,

transcend the framework of sociopolitical discussion that forms around Korean

society. The artist does not fling her own thoughts into interpretations or

assessments that package and present problems on the hidden side of Korean

society, with its tortuous path of modernization including war and forced occupation

by Japan, as finished stories. And she takes a very intimate approach to

comfort women, a subject that can be regarded as taboo and covered up in Korean

society. I believe she aspires to create a cautious and intimate relationship

with her themes. In Yangjiri Archive, too, she highlights the lives of the

migrant women living in the village rather than focusing on the political

issues surrounding the village, such as the inherent division and military

boundaries of the area. Choi’s working method explores the intimate life

experiences and memories of individuals, while marking out the trajectories by

which lives seen from a microscopic perspective gradually become history.

Perhaps she doubts whether all of these things really need to become history at

all.

Choi plans her works so that the particular situations and events

within the themes she addresses do not become objectified within history.

Perhaps the very act of attempting such plans is the role of an artist

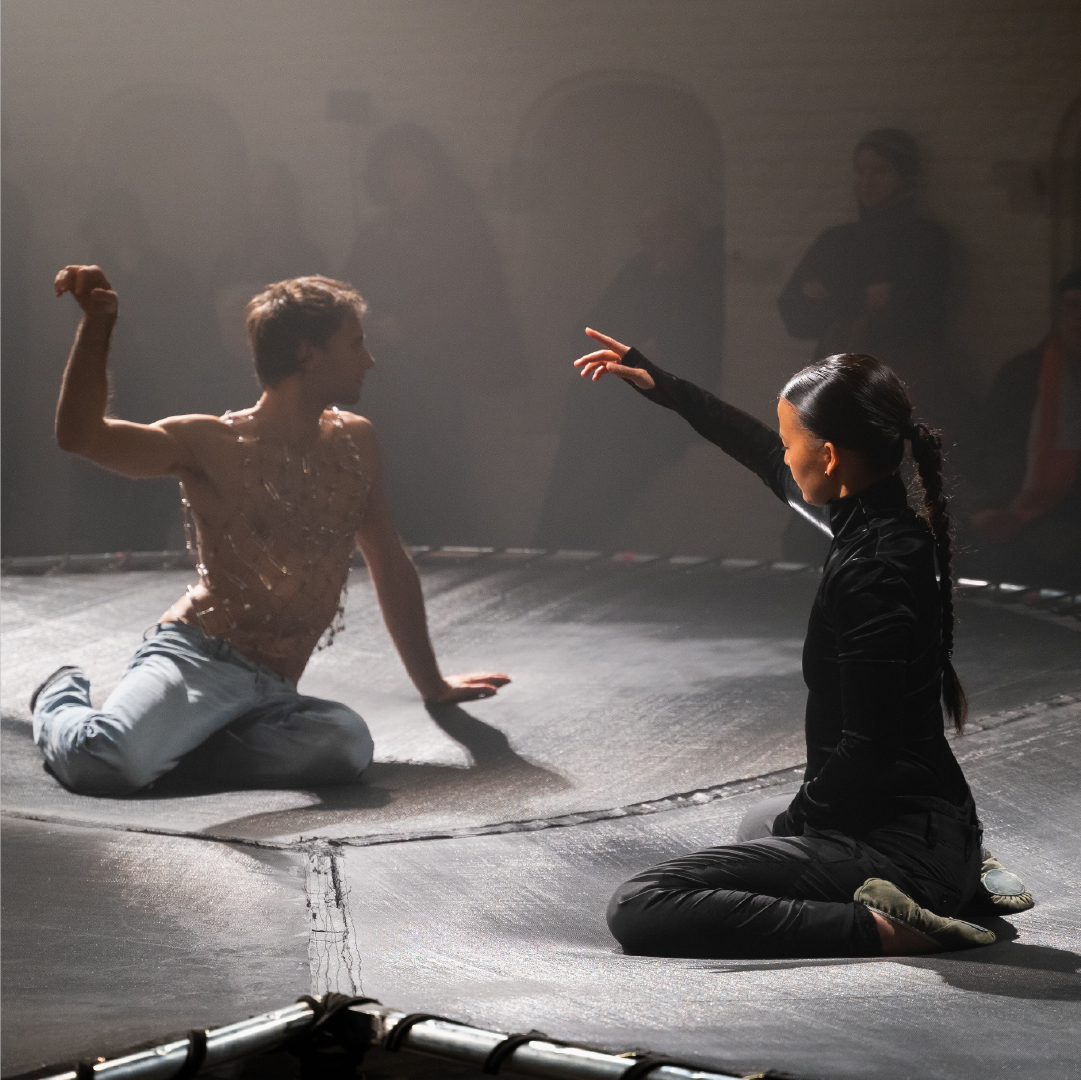

transforming history and women, incidents and people into works. Myitkyina is

the story of 20 comfort women forcibly taken to the Myitkyina region of Burma.

This work began with passenger records from the Maloha, a ship that sailed

between between China and India. History aims to represent records from the

past as factually as possible, but Choi’s Myitkyina takes

a diametrically opposed stance to this. Indeed, since there is not a single

witness and no extant testimony regarding the work, the artist derived her own

individual narratives from the characters in photographs. What skies would the

women in the photographs have seen in the unfamiliar land of Myitkyina? What

sounds would they have heard all day? Questions such as these build the

narrative structure of the work. Choi writes down “imaginary memories,”

meditating on the skies the women would have seen and the individual feelings,

such as fear of war, that they would have felt. Moreover the three women in the

video were each in Myitkyina for a different reason. Their various opinions on

how they came to be there are narrated: one was deceived into going; one went

after seeing a recruitment notice for comfort women; and one was illiterate and

had not been able to read the recruitment notice. Different opinions are thus

given for a single situation. This is also an aspect of explanations for

political situations, when a single incident is interpreted on various

different levels, or when totally different opinions are formed. And,

ultimately, the imaginary dialogues chosen by the artist were made possible

because they are the stories of comfort women who left no testimony. Our

problems, which exist, unresolved, despite Choi’s Myitkyina has

eliminated works that objectify the lives of individuals in order to elucidate

our own problems. She faithfully creates works that address how individual

narratives can become all of our problem.