I. Of linear and Westernized time

In 1884, the International Meridian Conference was convened in

Washington, DC, to fix “upon a meridian proper to be employed as a common zero

of longitude and standard of time-reckoning throughout the globe.” By

establishing a prime meridian, a fixed reference point, the conference

participated in enforcing a universal time standard. In other words, a system

of organization and control was established, which would regulate the lives and

structure of thinking in the rest of the world. It is this “Westernized time

construct”, as coined by art collective Black Quantum Futurism, which has now

reigned supreme for one hundred and fourty years.

Standing in stark contrast against this congruous landscape,

Sojung Jun’s new video, Syncope (2023),

foregrounds the toll hegemonic time standards have taken on bodies and souls,

proposing a new approach to experiencing reality. By manipulating and

collapsing space-time into a non-linear, thirty-minute-long video, the artist

brings about more desirable, possible futures. The montage, a blend of footage

filmed by the artist in Seoul, Yogyakarta, Paris, and Tokyo, as well as clips

generated with the Mobile Terrarium application, follows the mechanical

movements of the Trans-Siberian train, as it zips along across continents,

compressing the cities’ spaces and times.

Following the curvilinear journey of the train, spanning a length

of over 9,289km, Syncope’s premiere at the National

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea, is resonant. To Koreans living

in a divided country, the longest railway line in the world remains a highly

symbolic endeavor. Devised to rapidly connect Moscow to the Pacific port of

Vladivostok and expand trade between Russia and East Asia, the train represents

a missed opportunity for Korea and Europe to come closer.

Operating an aesthetic, cultural, and conceptual shift, Syncope

converts the Transsib into a hypothetical Ginga Tetsudō Surī

Nain (Galaxy Express 999) — a steam train running through the stars.

Directly referencing the Japanese manga series by Leiji Matsumoto, Sojung Jun’s

work embraces spacefaring. The narrative of her video conflates the temporality

of a Russian expansion into Manchuria and Korea, which the building of the

Transsib underpinned, and the fictional time of Galaxy Express 999,

wherein humans have learned how to transfer their minds into mechanical bodies

achieving immortality. It reminds viewers how Westernized time constructs and

connects nation-state building with space-time and speed management. At the

crux of Syncope, the Transsib allows Sojung Jun to

pinpoint to the railroad construction fanning flames that later led to the

Russo-Japanese War (1904-04), initiating a process which would end, much later

on, with the partition of Korea in 1955. The train is also conjured as

emblematic of our accelerationist times, its speed and linear path aptly

subverted by the artist. But maybe most importantly, the Trans-Siberian impacts

the film’s structure. To quote the artist, it acts as “a medium” for the video,

be that in the very first scene, in which small lights slowly enter the frame

from the bottom left and exit through the top right, or in the very last, which

emulates Star Wars unforgettable opening crawl. Within a black sky

featuring a scattering of stars, the generic text recedes toward a higher

point, as if it was disappearing in the distance; the way trees do, when stared

at from the inside of a running train. Throughout, the train’s windows operate

as screens, or as a framing device, delimitating our field of vision and

conditioning perspective. A temporary wall emulates this idea in the museum’s

installation, both revealing and obfuscating Syncope.

Suddenly, the horn resounds at a Korean train station. It’s time for the film,

and this text, to transition to their second chapters.

II. Bifurcations & labyrinths

In mathematics, the Bifurcation theory is

the study of changes in the topological structure of a given

family of curves.

It provides a strategy for investigating the bifurcations that occur within a

family.

In common language, though, a bifurcation is a fork in the road;

a break in the line. The train’s derailment…

Reinforcing its structural syncopation, Syncope forks

between two main characters, each of them a musician, each of them having

experienced their own derailment in life. “Maybe this is the beginning of the

second part of my life”, says Celia Huet, as she describes to the filmmaker her

move from France to Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Celia is the character we first encounter, in the starting sequence of the

film, but she appears for a mere instant, before a scenic clap, her

introduction into the work itself a syncopated entry. Adopted into a French

family from South Korea, she had already featured in Sojung Jun’s earlier

video, titled Interval. Recess. Pause1 (2017).

Her diasporic journey is at the core of Syncope, Indonesia serving as the

background for, and at times as the beating heart of, the film. It is in this

new home that she started practicing the Gamelan, a traditional ensemble music

of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up

predominantly of percussive instruments. In one of the crucial scenes of the

film, Celia explains having experienced a deja-vu or

a deja-entendu (already heard) when she first heard the music during

Indonesia’s annual Sekaten. Reflexively looping the work back onto itself, the

Gamelan, too, reemerges throughout the shots. The instruments’ sounds percolate

to the point at which it is hard to distinguish them from the soundtrack of the

work. In interviews, Celia highlights the sensory dimension of memory and

sound’s potential to bridge individual and collective experiences. This may

explain why, in Syncope, her recollections are often

carried over through sound rather than sight. Afterall, isn’t a syncope

synonymous to a memory lapse?

The second individual journey we learn from is that of Soon A Park, who also

featured in one of Sojung Jun’s Eclipse (2020),

and is the focus of the fourth chapter of Syncope. A

North Korean gayageum player, Park is from the third-generation of Koreans born

in Japan. Her parents moved to the country before Korea was divided, and

transited through to what is now North Korea where she studied gayageum before

settling in Seoul. As a player of a traditional Korean plucked zither, she

crisscrosses the cultures of Pyongyang, North Korea and South Korea in Japan.

Both Soon A Park and Celia Huet make manifest the bifurcations of

diasporic journeys, a space of inbetweenness that Sojung Jun favors. Discussing

her own relationship to the in-between spaces, the artist explained: “I’m

interested in liminal spaces – the things that happen on borders and their

ambiguity. (…) I put my passion into re-writing stories, time, and landscapes

of individuals who have been left behind by the speed of the city.” Throughout

her practice, concepts of translations and transliterations reappear, as

in The Ship of Fools (2016), in which she features

with three other characters, all taking part in an exercise of live

translation. By word of mouth, a sentence is chiseled and transmuted from one

language to the next, and the next, and the following. Syncope is

haunted by those images of roads intersecting, sometimes symbolically, like in

this Indonesian graffiti of a woman with pigtails which is no other than Celia,

crossing borders. I am reminded of Vietnamese poet Vi Khi Nao writing about her

own family’s exile: “In the exodus mayhem, shrapnel and shards of glass sliced

a chaotic cartography of scars on my grandmother’s body, creating bifurcated

roads of the war I could use later as map and compass to find my roots.”

The mythological figures of half-demigods Karna and Bari are similar

invocations. Both represent nomadic identities hovering between life and death.

They act as secret amulets, protecting the wanderers during their diasporic

journeys. While Karna is described as the secret son to an unmarried

Kunti, who, fearing outrage from society over her premarital pregnancy,

abandoned her newly born in a basket over the Ganges, hoping he would find

foster parents, Bari guides the souls on their way to the land of the departed.

I am reminded of the spirit of Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára, the Trickster God of

Crossroads; of Beginnings and Opportunities, who provides second chances… All

are liminal deities. But what I liked about Èṣù-Ẹlẹ́gbára is that it is said to have control over the past, present,

and future. Often, the spirit is depicted holding a set of keys. As a

trickster, it plays time. Bypassing linear constructs, modernist like

accelerationist, it derails…

In common language, though, a bifurcation is a fork in the road; a

break in the line.

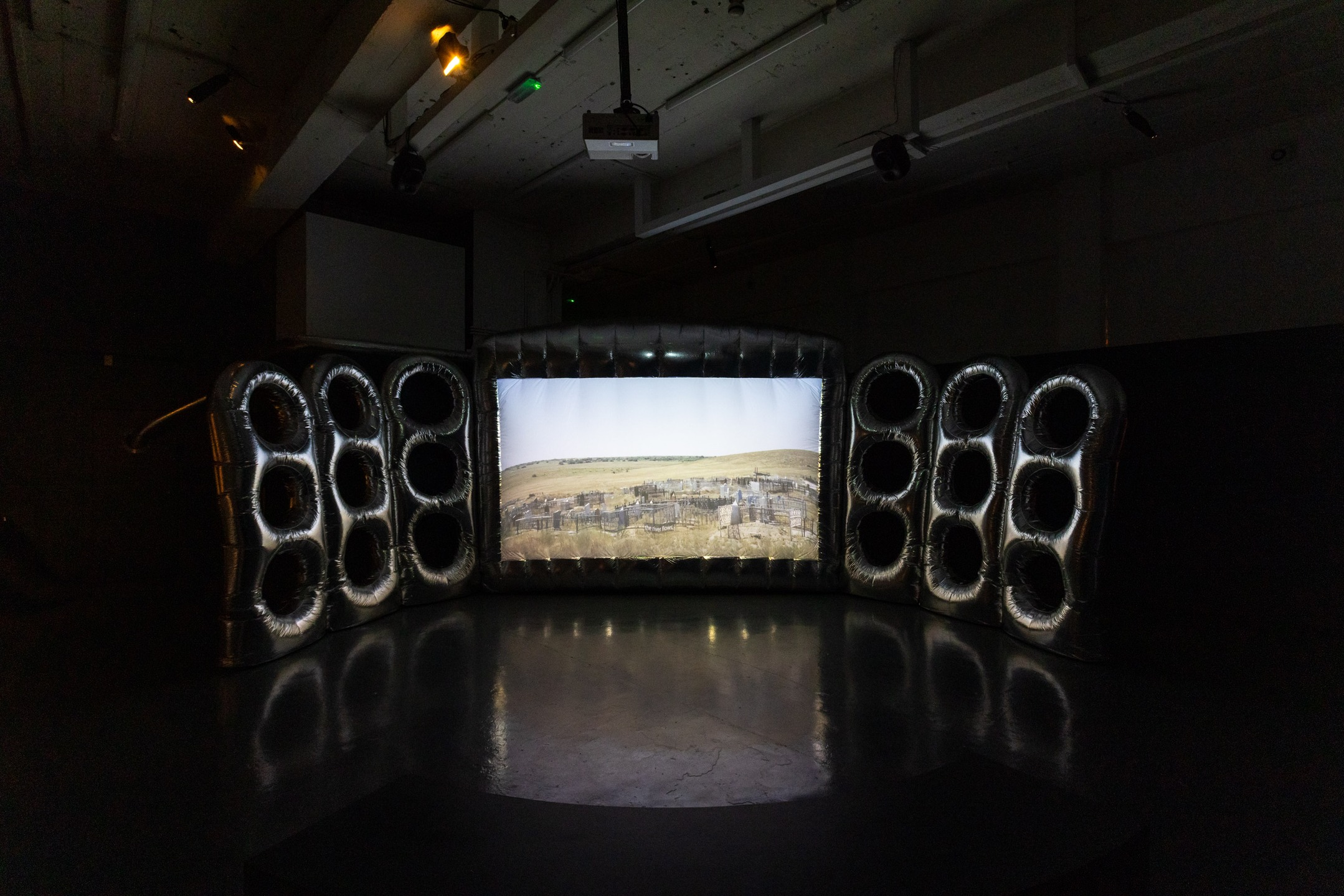

Sojung Jun’s exhibition evokes a labyrinth. It invites visitors to

transit through a series of installations before reaching the newest of her

works, created for the presentation. One of the first they encounter is Despair

to be reborn (2020), a maze-like sculpture of metal, which

organizes a video and a set of sculptures in a runway of curvilinear bars

reminiscent of department stores. The video refers to an early poem by Yi Sang,

born Kim Hae-Gyeong (1910-1937), one of Korea’s most renowned modernist poets,

intersecting contemporary and modern Korea. In this text, titled Au

Magasin de Nouveautes, the author questioned the concept of the

“modern”, problematizing its connection with capitalist economy. Curator Ahn

Soyeon2 who first exhibited Sojung Jun’s video highlighted the

poem’s enigmatic quality: it combines “a French title” with “Japanese,

classical Chinese characters, Chinese and English.” Kim Hae-Gyeong, like Celia

Huet in Syncope, inhabit a language I call diasporic

—the space of roads that bifurcate.

The installation Despair to be reborn problematizes

some of these diasporic questions. Despite its futuristic look, the maze hints

at the design of 19th century Wardian glass houses, oscillating like the video

between the future and the past. A product of British imperial pursuits, these

terrariums were invented by medical doctor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s to

transpose foreign plants into his own geography and time. In 1842, in his

essay “On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases,” he elaborated on the

experiments he started in 1833, explaining how he shipped two glazed cases

filled with British ferns all the way to Sydney. One can read that after a

voyage of several months, the plants arrived in good condition. Reading about

it though, I wondered how many other plants had died as a result of his

colonial quest for botanic knowledge… Sojung Jun studied Bagshaw Ward’s cases,

and transposed them into the digital world, creating 3D animated sculptures in

an application called Mobile Terrarium. These “escaped garden plants,” as she

calls them, spread from seeds of the epiphyllum plant, a tropical succulent

species that also appears in Syncope. Shown in the

video, and accessible to all via the app, the plant-sculptures can be carried

into a new setting. Like humans, they may “live here” and still “desire another

place”3, like Celia, who in the fifth chapter

of Syncope mentions her difficulty to “adjust” to life in France.

Epiphyllums are ‘queens of the night’; they bloom only at night and close themselves

again before the sun rises. As alien plants, they are “not here to stay”4.

Not unlike Youssouf, 4 years old, and Yunus, 2 years old, who sailed from

Turkey to Greece, raided by waves, and whose journey is mentioned in Sojung

Jun’s work The Ship of Fools, a little further in the

exhibition5.

“Lastly, in the field of mathematics, the Bifurcation theory is

the study of changes in the topological structure of a given family of curves.” This

came back to my mind as I first sat through Syncope. In

the video, each chapter is introduced by a drawn-out curve; each a specific

wave pattern. As it reaches its end, almost beyond the generics, all the curves

reappear, like a series of bifurcated paths gathered together again…

III. A sudden drop in oxygen supply

In 1993, discussing the theoretical, historical and social

framework he called the Black Atlantic, sociologist Paul Gilroy6 explained

the effects of “syncopated time” as both counter-culture and constitutive of

modernity. The following year, historian James Clifford published his

article Diasporas7, which further emphasized

the productive possibilities of syncopated time, wherein “effaced stories are

recovered” and “different futures imagined.” It is helpful to keep those in

mind as one journeys through Syncope.

The title of Sojung Jun’s work hints at a medical context: the

short-term cognitive trouble caused by a sudden drop in blood oxygen supply in

the brain with, at times, slowing down or interruption of the pulse. While the

return to consciousness is most often spontaneous, syncopes bear an intimate

relationship to death. They represent the body’s most ultimate loss of control;

an interruption in the beat; a disruption in both music and narrative. One of

these regular interferences is the artist’s microphone, which reappears in

various scenes: at a railway crossing; when the story of Karna is told. It

grabs our attention, disrupting our disbelief’s suspension, interrupting a

flow, and ultimately reminding us of the filmmaker’s existence.

However, it’s in the editing that the syncopation operates at its

best. In various scenes, the screen splits into three vertical windows, the

video’s landscape segwaying into fragmented views. While the middle section

remains sharp, as if filmed by the phone of a camera, the background image,

which appears to the left and right of the central vertical window, lays out

enlarged and pixelated sights. It repeats, with a variant, what appears in the

center of the frame, making us lose a bit of perspective. Amidst a sea of

pixels, Sojung Jun deliberately creates a central path for our eyes to journey

on. As author Catherine Clément puts it: “the syncope will always make a fuss:

it cannot be discreet, it demands to be seen […] It shows off, exposes itself,

smashes, breaks, interrupts the daily course of other people’s lives, people at

whom the raptus is aimed.”8

As the film progresses, the rhythmic elements of the video

conflict further and further with its tempo and measure, as if the narrator was

travelling to the speed of light, à contretemps. It’s at that moment that

South Korean musician and DJ, Lee Sowall, takes center stage. Set against a

blurry background, she is filmed finger-drumming, but her body and table seem

to escape the frame, deriving beyond gravity. The image against which she

stands turns into a decelerated image of central Seoul, pictured from a train,

but slowed down to the point of staggering. And suddenly the train derails. A

leap out of the space-time continuum. “In the end, we all move at different

speeds,” says Sowall. “We live in the gaps.”

I remember asking myself what lived in the intervals when I first

saw Himali Singh Soin’s video The Particle and the Wave (2015),

in which the artist studies the rhythmical pattern of Virginia Woolf’s The

Waves. Working through the author’s novel, Singh Soin erased the

words to only leave the semicolons behind as hinges to help us measure time.

What lives between the beats, the words, the times? Are there plants, mycelium,

that spreads and grows surreptitiously like Sojung Jun’s epiphyllum? What lives

in the off-key sounds of the Gamelan?

In one of my last emails to Sojung Jun, I asked her to tell me more about the

concept of Nonghyun, central to the gayageum’s left-hand technique

mastered by character Soon A Park. She responded: “nonghyun is an

unwritten sound,” “a void,” “the margins of sound that goes outside the

notation.” Funnily, in one of my obsessive digs about the work and Lee Sowall,

I read an interview in which the journalist inquired about the precision of her

beats. Asked how she managed to remain so precisely on beat without an obvious

click track, Sowall too praised the interstice: “I’m obsessed with tempo,

which can work for you or against you. It comes naturally to me to lock in to

the beat. But when I’m finger drumming, I try to forget what I cared about when

I played the drums.” “I’m a little bit more free.” “Finger drumming has been a

getaway to escape.” How does one operate from a counter beat perspective, that

very “counter beat” which Paul Gilroy called upon in his book, Black

Atlantic. The Gamelan, whose actual name comes from the Javanese word

gamel, which refers to the act of striking with a mallet, in other words the

beat. But what makes it unusual, and connected to the gayageum, is that it

relies on an ensemble working on scales that are not standardized. Within one

set, each instrument is deliberately tuned off so that resonance occurs only

when all are struck simultaneously. Dissonant to the point of harmony…

In the text accompanying her eponymous show9, art historian Daria

Khan wrote: “a syncope is a multi-format ‘tender interval’ which can be

described in music as an unstressed ‘empty’ beat; in linguistics as the

suspension of a syllable, or a letter; in medicine as a partial or complete

loss of consciousness. In this exhibition, syncope acts as a metaphor for

rapture, delay, lacunae, and displacement.” As she would, I ask: can the

syncope create an additional, unstressed beat, in the interstice, for a

different time-space continuum? Phonologists and linguists came up with a

concept for this idea: they call it the helping vowel. It refers to a rule of

pronunciation that inserts a “brief” vowel as a vocalic release to help us

pronounce a word with more ease. A surplus sound, if you will. The very last

scene of Syncope occupies the very space of that interval. After the train has

reached the speed of light. At its climax, the video takes on a most

experimental quality, suggestive of avant-garde cinema, with its showing of

sprocket holes, splice marks, and flickering. As Sowall finishes her set,

afterimages of her body appear in a staccato of slow-mo, like a comet’s tail

lingering in the sky, glitching.

Right as I reached the last line of this text, I received a

mysterious PDF document titled “Clues.” In it, Sojung Jun

revealed: “nonghyun is the most characteristic and important

technique in Gayageum. It produces various decorative sounds in addition to the

original note. As it is not notated; it is both objective and subjective;

resolute, like a big wave.”