Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Hayoun Kwon has participated in approximately

11 solo exhibitions across various countries, including Korea (Seoul), the

United States (New York, Berkeley), France (Paris, Châteauroux, Lectoure), and

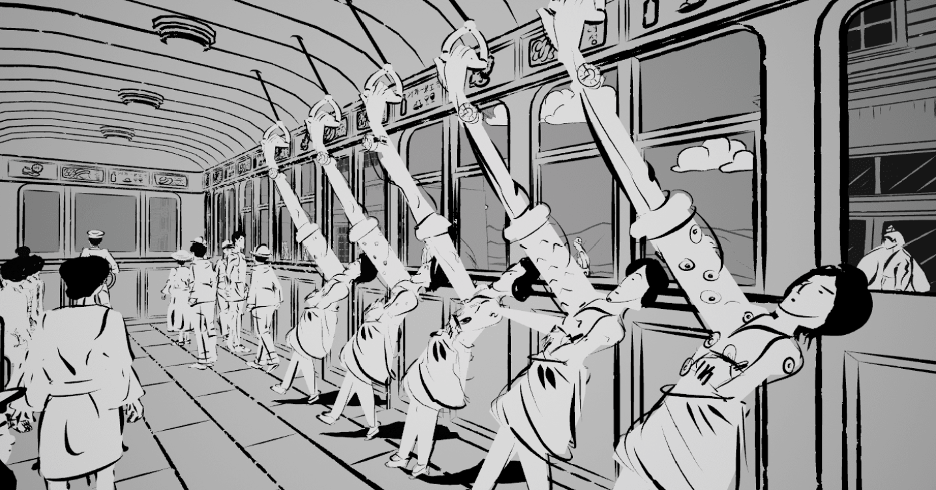

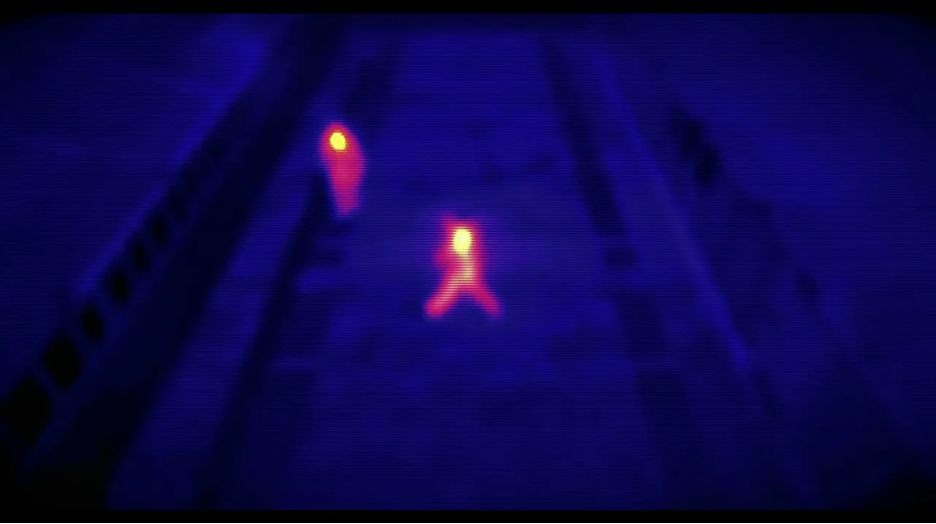

China (Shanghai). Her major solo exhibitions include 《Le voyage

interdit》 (2015, L’École des Beaux-Arts de Châteauroux,

Châteauroux, France), 《Le Paradis Accidentel》 (2015, Galerie Dohyang LEE, Paris, France), 《489 Years》 (2016, Le Centre d’Art de

photographie de Lectoure, Lectoure, France), 《The Bird

Lady》 (2017, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France), 《J’entends soudain des battements d’ailes》

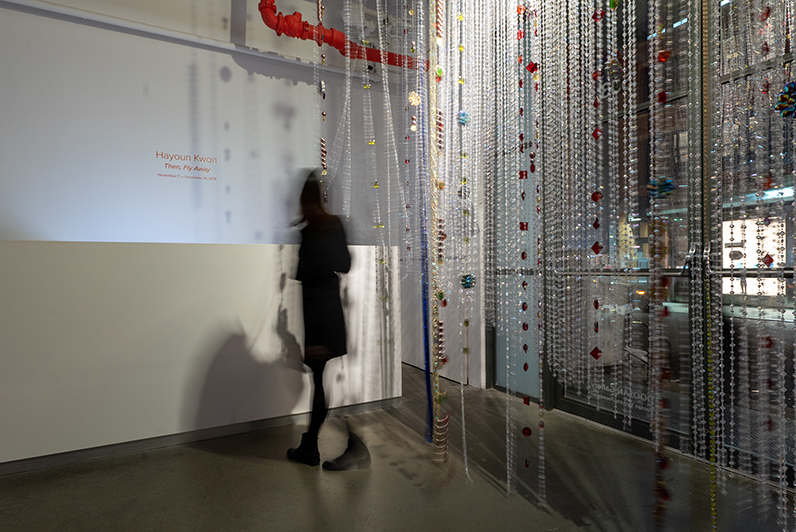

(2018, Galerie Sator, Paris, France), 《Levitation》 (2018, DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, Korea), 《Then,

Fly Away》 (2019, DOOSAN Gallery, New York, USA), 《Si proche et pourtant si loin》 (2019, ARARIO

Gallery, Shanghai, China), and 《Strange Walkers》 (2023, Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Hayoun Kwon has participated in approximately 63

group exhibitions and screenings across various countries, including Korea, the

United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Luxembourg,

Israel, Bosnia, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Iran, from 2006 to the present

(2025).

Her selected group exhibitions include

《Inhabiting the World》 (2014,

Busan Museum of Art, 7th Busan Biennale, Busan, Korea), 《REAL DMZ PROJECT》 (2015, Art Sonje Center,

Seoul, Korea), 《Digital Promenade》 (2018, Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea), 《Immortality in the Cloud》 (2019, Ilmin

Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea), 《Rumeurs et légendes》 (2019, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France), 《The Gold Rush》 (2020, Ilmin Museum of Art,

Seoul, Korea), 《Global(e) Resistance》 (2020, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France), 《XXth

Attempt Towards the Potential of Magic》 (2021, National

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea), 《The

Shape of Time》 (2023, Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Philadelphia, USA), 《Remembering/Sensing – Community of

Experience》 (2023, Asia Culture Center, Gwangju,

Korea), 《Watch and Chill 3.0: Streaming Suspense》 (2023, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul,

Korea), 《Open Systems 1: Open Worlds》 (2023, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore), and 《Korea Artist Prize 2024》 (2024, National

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea).

Her screenings include 《Geneva International Film Festival》 (2023,

Geneva, Switzerland), 《Tribeca Film Festival》 (2022, New York, USA), 《REPLAY THE FUTURE 8》 (2022, Fondazione MAXXI, Rome, Italy), and 《Video At Large – Intimacy》 (2022, Red Brick

Art Museum, Beijing, China / Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris, France).

Awards (Selected)

Hayoun Kwon has received several prestigious

awards, including the DOOSAN Artist Award (2017, Korea),

the Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction (2018, Austria),

the NewImages Festival Prix Spécial du Jury – LBE (2022, France),

the Tribeca Film Festival StoryScape Award for Best Immersive

Experience (2022, New York, USA), and the Geneva International Film

Festival REFLET D’OR for Best Immersive Experience (2023, Switzerland).

Collections (Selected)

Hayoun Kwon’s works are housed in the

collections of major institutions, including National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art (Korea), Seoul Museum of Art (Korea), Centre national des arts

plastiques (France), Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (France), Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific

Film Archive(USA).