The Embodiment of True-View: Jin-gyeong

Assuming that there is a proto-imagination vis à vis Western

painting to discuss conventions of contemporary art, ponder this: How does

painting represent itself? Trained in classical Korean painting methods, Suki

Seokyeong Kang (b. 1977, Seoul) utilizes sound, video, sculpture, and

installation to produce a conceptual framework around what painting means,

making use of

a unique vocabulary, including various archaic Korean concepts, to shrewdly

materialize her subjects. The components of Kang’s oeuvre have brought together

art forms rooted in tradition, but employ contemporary modes of expression.

They examine the sustainability of traditions and expand both discursive

responses to contemporaneity and their significance to modern and contemporary

art.

In traditional Korean Art, true-view landscape painting

(jin-gyeong sansuhwa), influenced by Wu Wei’s Taoist philosophy, is based upon

concepts of artistic nonaction and noninterference with the order of the

natural landscape. Only inspiration drawn from natural landscapes allows the

artist to reflect upon and interpret the harmonious coexistence of humans and

nature. One of the pioneers of true-view painting during the Joseon Dynasty,

Gyeomjae Jeong Seon (1676–1759), developed Korean true-view subjectivity beyond

that of the traditional Chinese Southern School (nanzhonghua) and esoteric

literati painting styles. To Gyeomjae, true-view painting not only represented

scenery itself, but also embodied artistic interpretations of that scenery.

What was important about Gyeomjae’s painting was not merely the ability to draw

landscapes by “imagining” them from the artist’s vantage, as the Chinese did,

but something closer to the actual incarnation of the “true-view movement,”

which relied upon the artist’s minimal engagement with the scenery.(1) In this

manner, true-view became the philosophical extension of the artist’s subjective

view of the landscape, as well as a way of embodying the artist’s experience of

space and time.

It would be quite difficult to distinguish the viewer’s

perspective of the scene in Kang’s work in relation to her new formats of

conceptual painting as influenced by true-view, as well as her complex

interplay with materiality, including the visual and the metaphysical meaning

of art as a whole. Although it seems simple enough to conjure a question about

whether the canvasless modality evokes the extended structure of discursive

painting as Kang intends, one further wonders what this synesthetic yet performative

visuality means. Here the artist’s related sets of repetitive techniques

minimally intervene in an incommensurable constellation of themes, shapes, and

narratives. Since Kang’s artistic vision is based upon intermediality, the

nondirective interaction between subject and object, and the manifestation of

actuality, her subjects phenomenologically transform specific time space into

transitivity, the constant transition and/or transformative archive of mind

that engenders delicate senses and individual meanings to the spectators.(2)

Transformative Grids: Squares of Jeongganbo

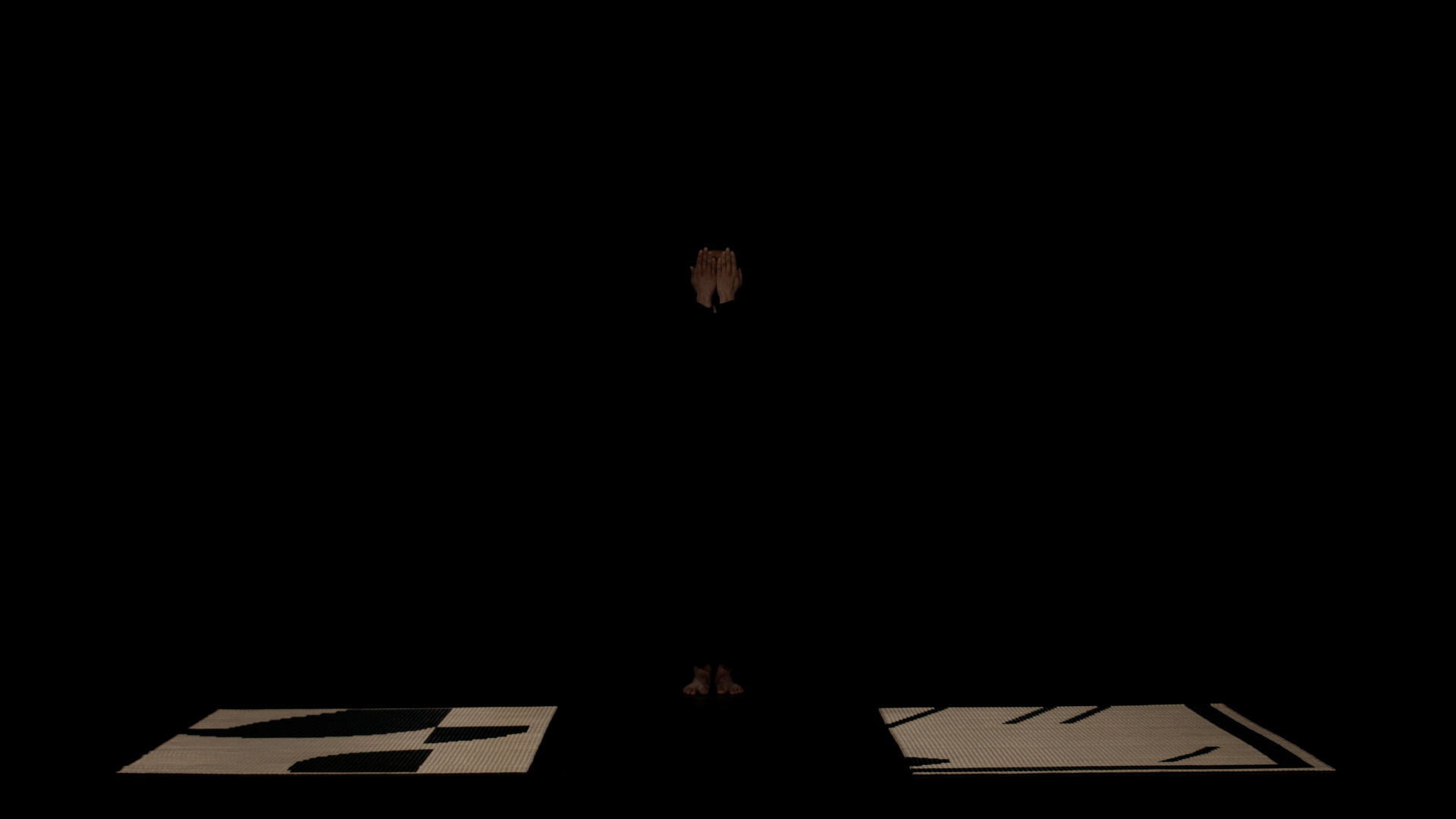

In works such as Black Mat Oriole (2018) and Black

Under Colored Moon (2015), Kang redefines her own notion of painting

through the use of a pitch black screen that becomes a conceptual handmade

canvas, recalling the classical Korean painting motif of the hwamunseok (black

mat), as well as the Korean musical notation jeongganbo. Jeongganbo was the

first musical notation of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), produced by King

Sejong, to provide greater access to the public. This ancient form of musical

annotation is an indispensable cultural reference for Kang’s works, since

jeongganbo possesses two primary functions: as an auxiliary memory system to

extend playing instruments visually, and as a sign to communicate and visualize

sounds among players. The traditional musical notation as a supplementary

memory system connotates a command system that tells musicians what to play,

while each musical notation in jeong signifies a visual substitute for the

actual sound, which indicates an expression-based system used to think about

sound itself, similar to Hangeul (Korean alphabet).

One might wonder why Kang chooses to utilize musical annotation

from the Joseon Dynasty. Although Kang’s oeuvre is characterized by various

techniques she employs in her own version of traditional painting, the minimal

set of geometric jeong (井) in jeongganbo

is not merely a metaphorical extension of the artist, but a profound reflection

of Kang’s spatio-temporal visions, brought to the surface by forgotten

compositional traditions. Simply put, jeongganbo is a well-shaped square which

indicates an interval of time between sounds, thus inscribing the length of

sound into the scale of the space. It conveys a series of in-between sonic

gestures, such as the pitch of a sound (yulmyeong), an omnibus sign (oeumakbo),

a joint sign (hapjabo), and a footnote (yukbo). As jeong is a minimal form of

writing, the fragments of each jeong in Kang’s works are extended virtual

canvases for her “performance of becoming painting,” which invoke both

musicality and choreography in her static objects. In Kang’s works, jeongganbo

becomes a unique orchestration of trueview, implied through the multiple

connotations in each liminal square and activated as fragments of

spatiotemporality.

In the video installation Black Under Colored Moon

(2015), two elderly performers slowly move – not as “performance,” but rather

“becoming a moving painting” – in imperfect synchronization to geometric

tectonics that seem both exact and imprecise. Kang’s pieces are all similarly

marked by elements of harmonious incongruity. It was loosely inspired by the

oral literature genre Goryeosokyo, in particular the text Ssanghwajeom, which

literally means “dumpling shop,” and was anonymously composed and orally

transmitted during the era of King Chungnyeol (1236–1308).(3) The narrative of

Ssanghwajeom is based on unabashedly explicit sexual conversations between men

and women, often performed at the banquets of military commanders who enjoyed

the time’s peculiar style and aesthetic. The Goryeosokyo songs were revised

during the Joseon Dynasty under highly demanding Confucian morality and

chastity.

What is crucial about Kang’s appropriation of Ssanghwajeom is not

the contents of the sub narrative itself, but the way in which she uses the

song’s refrain as an intermedia reference. In Goryeosokyo, each stanza

possesses a specific meaning, sometimes freely improvised and modulated by an

audience’s perspective, such as gender difference, sociocultural hierarchy, and

the exchange of interracial heterosexual desire. In Kang’s work, this

transforms the subject’s positionality and clandestinely reveals the audience’s

subversive pleasure and imagination through linear and nonlinear narrative

structure. In Black Under Colored Moon, two elderly performers, each moving on

either side of the screen, slowly and individually deal with their bodily

rhythms and repetitively reprise the ending and departure of their intermittent

rendezvous to the stanzas of Ssanghwajeom. Since the objects of this

installation are not fixed in their connection, they loosely navigate through

the bodily movements of the performers. They meet with each other as if

improvised and intentionally modified, in-between anthropomorphic sculptures

accumulated by a series of affectual transformative grids.

In Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, Walter J.

Ong proposes that twentieth-century electronic technology is bringing back oral

culture.(4) If we posit Black Under Colored Moon as the secondary orality Ong

notes – transmitted through media such as television narratives – we find it

shares many similarities with verbally transmitted primary orality (e.g.,

folktales, rumors, and oral history), unsurprising since Kang’s Black Under

Colored Moon was influenced by the form of Goryeosokyo.(5) Still, there are

differences. Ong argued that secondary orality is not as repetitive, redundant,

or agonistic as primary orality. Here, Kang’s pieces betray the visualization

that separates secondary form primary orality, and mark its return. Secondary

orality, according to Ong, is essentially “a more deliberate and self-conscious

orality, based permanently on the use of writing and print.”(6) In Black

Under Colored Moon, Kang uses a variety of printed materials on her

virtual canvas – from hanji paper, brass bolts, and steel to thread, wood,

plastic, and leather – to reconstruct her own concept of moving painting by

appropriating the narrative of Ssanghwajeom, so that despite the minimalistic

nature of her pieces, the work produces a sense of tactility and palpability. I

now return to the question: Why does Kang sum-mon past mnemonic techniques and

reconnect them to contemporary modes of making? What is the relationship

between her appropriation of true-view and her way-of-seeing and recognizing the

world?

Painting as Dispositif: Affective Spatiotemporality

Readings of tradition in Kang’s work lie in the fact that there

are two traditions engaged:

a past as referent or sub-narrative theme and a past that’s “immanent to its

praxis.”(7) Kang’s expanding aesthetic of true-view shows that her concept of

spatiotemporality as the organic connection to time and space, and the

audience’s affective feeling of “being here” individually and collectively,

work together in ways particular to the artistic mode of her vision. Thus,

Kang’s unique configuration of spatiotemporality from a past to interweave the

present/future engender an individual and collective sense of time/space,

leading to the use of multifarious interpretations to negotiate the very

meaning of contemporaneity.

The row of installation pieces in Pause and Position – Jeong (2012–2015) may

at first appear almost symmetrical, but upon closer observation, are slightly

mismatched. Kang’s work, in general, can appear structured but fragmented,

geometrically harmonious but delicately disjointed, careful but makeshift. When

we view this work through a broader contextual lens and contemplate what it

means to understand contemporary sensibilities within the structure of

tradition – or what happens when we transfer meaning across cultural,

chronological, or spatial boundaries – Kang’s approach seems both eloquent and

earnest. Her geometric perceptions further both the individual meaning of works

and the ongoing evolution of true-view painting, reified as an ongoing process.

True-view painting functions as a Foucauldian dispositif, a term

that describes the construction and rearrangement of images, and their

heterogeneous connection to reinterpretation by the audience.(8) In media

studies, the dispositif has been engaged by Post-Structuralist approaches to

film, such as the apparatus theory. The concept of the dispositif was promoted

and expanded in the 1970s by Christian Metz, a theoretician who incorporated

psychoanalysis into film theory, by focusing on the symbolic representation of

reality through movies. In other words, when the dispositif connects viewers

and spectators to the outside, the viewers generate new meanings as they

acquire understanding of the cinematic unreality, or the way affective

influences simulate reality through visual representation. Both Kang’s Black

Under Colored Moon and Black Mat Oriole produce

grounds for the audience’s experience of a dispositif, in which the

connection-convergence-interaction between philosophical and existential thinking

occurs. This function is actively applied and appropriated in Kang’s works, as

actual (sculpture) and virtual (video) aspects offer up both the real world and

its simulation.

The audience’s experience within Kang’s sculptural installations

echoes the fragmentation of her videos as déjà vu, which reifies a feeling of

connection. The deactivated objects, without agency, that the audience

confronts virtually on the screen enunciate their physical existence as if they

(Kang’s artistic objects) are the proof of the memory. The assemblage of

numerous grids on the screen can be arbitrarily combined at any time in the

actual site through the audience’s own imagination – introducing different

realms of reality. Thus, actual objects seem to provoke questions about the

ontology of virtual things – how the visual (what-you-see) can be mediated as

linear, and how, combined with non- linear narrative structures imagined by the

audience, can actually limit the way we perceive thingness, the very essence of

true-view. The paradoxical meaningless in the realm of interpretation and

aesthetics acts as a Heideggerian project (Entwurf) of self-contemplation and

reflection, such that in contemporary true-view, various historical and

cultural meanings can be intermediated behind void signifiers.

Subversive Porosity: Holes and Circles of Hwamunseok

In Black Mat Oriole, we zoom in on Kang’s

faceless subjects constructing structures with intention, and yet their

mysterious movements seem unsteady; pieces of pastel shades don’t seem to

completely align in the midst of the visual cacophony. Within the epistemic

matrix of hwamunseok (black mat), another artistic platform for Kang’s work,

uncanny noises ooze out of the apertures, bodiless feet slowly hop around

be-tween stanzas, and porous squares permeate the spatiotemporality of

beings.(9) Each cadence of movement ends repetitively with the clear sound of

percussion, which plays a role in informing the beginning, ending, and change

of action.(10) Those who are situated in their own space-time start to break

away and sneak into other places, taking their feet in and out of the holes in

a pitch black diegesis, where ominous shadows appear, as if monitoring the

entire sequence.

For Kang, the metaphor of porosity evokes political engagement, in

terms of both contemporaneity and the way-of-seeing in South Korea. Since

Kang’s Black Mat Oriole indicates that the multi-layered

precondition of being that had long been confined in a small square as jeong,

is no longer constrained within the absolute spatiotemporality; rather the

subjects can instantaneously engage, expand, overlap, and interfere to affect

one another. The political transversality of porosity thus opens up a question

about the permeability of the self. Unlike Kang’s previous artistic motifs,

such as Mora and Jeong, why does the hwamunseok in Black Mat Oriole have so

many holes and circles, and what do they indicate to us as signs? To better

understand the trans-formative links between Mora/Jeong and hwamunseok, we

should remind ourselves of the historical specificity of Black Mat

Oriole, as Kang’s work is considered within the sociopolitical

circumstance of South Korea.

The installation of Black Mat Oriole is

inspired by one of the most beloved traditional solo court choreography forms,

Chunaengmu (also known as Chunaengjeon, literally meaning “dance of the spring

oriole”), from the late Joseon Dynasty.(11) Created by Prince Hyomyeong

(1809–1830), who was inspired by watching a pair of orioles chirping on a

willow branch, Chun aeng mu is a series of restrained gestures with gentle and

poetic movements, only to be performed on a square mat, called hwamunseok.(12)

In other words, hwamunseok is the only choreographical topos in which anything

can be allowed to be presented. During the traditional solo performance, the

court music piece Pyeong jo hoesang is played to accompany the dance, though

Kang uses minimal sound to evoke its nature.(13) Since it is a court dance only

performed in front of royal family, its expression is full of

self-restraint.(14) The most striking pose of Chunaengmu is hwajeontae (花煎態), literally meaning “the graceful appearance in front of a flower.”

Performers in court dances could not dare to face the king. Hwajeontae is the

only exception – as when the dancer imitates a bird resting on a flower by

placing their colorful sleeves behind their back. Only then can the dancer

smile at the king. The quality of this unexpected smile reveals the class of

the dancer, since the very act of smiling is one of the most audacious and

subversive pinnacles of hwajeontae. The momentary act is the only time-space

when both the performer and the audience can be hierarchically equal,

regardless of their sociocultural status. Thus, the truth of meaning can be

fully conveyed within this ecstatic interstice. As Kang clearly indicates,

hwajeontae serves as a minimal artistic platform for “the minimum space one can

stand in… it simultaneously becomes a point of departure and point of arrival,

after which we decide where we want to go,” or better, hwajeontae might signify

the political condition in which one can investigate the concept of

dispossession in contemporary Korean culture, and its connections with

bio-politics, recognition, performativity, protest, and relationality.(15)

Regardless of Kang’s ambiguous intentions, Black Mat

Oriole clearly resonates with Korean political turmoil instigated by

the Sewol ferry incident (2014) and the public’s active engagement both

collectively and individually in response to these historical moments.(16) The

attitude of these personal movements informs the poiesis of what Kang wishes to

explore, just as Chun aengmu’s hwajeontae uses perpetually mismatched holes and

seemingly unfit circles in repetition as signs for the metaphorical socio-political

movements of the individuals in motion.

The Sewol ferry incident was the signpost for Koreans to rethink

meanings of contemporaneity that they took for granted since their liberation

from Japanese occupation. The biopolitics of the Sewol ferry incident raise new

cultural concerns around sovereignty, dealing with topics ranging from

conditions of Giorgio Agamben’s “bare life,” the rights to live, questions of

governmentality related to the “disjointed time” of the sinking, as well as

issues of the governmental control of human right movements. Since 2014, the

South Korean search for trapped spatiotemporality is always, and repetitively,

concluded as the search for truth. But, as Gilles Deleuze said, “the truth is

not to be found by affinity, nor by goodwill, but betrayed by involuntary

signs.”(17) There are signs that force us to conceive this lost time under the

government’s control through political movement and cultural censorship. For

unknown faces, no-longer existing faces, continuously born in pure states as

the signs of mismatched spatiotemporality, have been re-modified by the media

in blurred and crushed moments. Affect lingers in the past and the present

reappears on the surface – these mediatized signs give us the pain of

witnessing and constituting a time lost forever, instead of giving us hope for

the future.

Suffice to say that the present sensation sets its materiality of

culture, and gives us a sense of irreparable loss as a present sensation – the

strange contradiction of survival and of nothingness, both evaporated moments

of narrative. As Kang mentioned, the narrative within specific

spatiotemporality can create the potential to move on and undermine the very

situated-ness of a subject’s past, present, and future.(18) In Kang’s Black Mat

Oriole, this creates a specific place and time that resonates with the movement

that reflects our own position, which allows time to flow toward the future.

Memory and trauma appear in several signs: desire, the imagination of life and

death as departures and endings, lost/disjointed time-spaces, repressions and

disappearances, absences and losses. The uncovering of these in Kang’s Black

Mat Oriole – whether voluntary or not – gives meaning to our

repetitive trauma through the perpetuation of specific spatiotemporality that

mirrors contemporary Korean society.(19)

Coda: The Archive of Future Memory

Of whom and of what are we contemporaries? What does it mean to be

contemporary? – Giorgio Agamben(20)

Among all the Joseon dance performances, Chunaengmu was regarded

as the supreme aesthetic essence of court dance and symbolic etiquette.

However, due to the abolishment of the Joseon Dynasty’s class system and

practice of slavery by Gabo reform in 1895, the gisaeng dance performers, as

well as the institution set up for training and oversight of the dance,

disbanded amid the historical vortex of declining traditional art. Only a few

performers from former gisaeng households tried to succeed in this traditional

art during the Japanese colonial period.(21) In 1969, the Korean National Film

Institute produced, Chunaengmu, a propaganda film (director unknown). This

now-rare film is based on the story of an elderly gisaeng in the colonial

period, who entrusted her assets to a national bank to secure economic

stability after liberation, and tried to pass on the movements of traditional

dance to her daughter.

Although the film was originally created to promote the saving of individual

assets at national banks, it symbolized the compressed modernization and

economic development of Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship – the plots, sequences,

and narrative of the film evoke the forgotten memory of Chunaengmu and gisaeng,

materialized through glimpses of archival footage of Chunaengmu performances

and the lives of its female entertainers. In the vividly represented monologue

of the old gisaeng in the final se-quence, the main character recalls her past:

My heart is now relieved. Today I put on my daughter a new yellow

colored aengsam with headdress that I wore to dance. After that, I didn’t live

long. Of course my daughter would have struggled and cried. But I want to say

that I have been honored by my daughter even in the afterlife. I always wanted

to keep my words in my daughter’s heart. Walk as if your feet are floating off

the ground. The body should be ridiculously light so you can sustain your own

weight with patience. When you smile, you should make yourself feel a vague

elegance with climax. Move as swallows fly back to the nest. Make your heart

attractive so your movement is equally gorgeous.

What does it mean to be honored by her own daughter, a successor

who remembers the forgotten choreography in the midst of the dictatorship?

Following postcolonial theorist Dipesh Chakrabarty, I ask a question: Who

speaks for the Korean past, and who will be the successor in the archive of

future memory?(22) From Japanese sexual slavery survivors to the US military

camp sex workers, the marginalized voices of the subaltern became a symbol of

collective resilience, a kind of “transnational feminism against the unresolved

gender and ethnicity based atrocities.”(23) According to Hyunah Yang, these

testimonials – narratives of self- representation in which each woman looked at

herself and her experiences reflectively with her own strength of

interpretation – and their repetition of narrative triggered the map of

memories that eventually unfold and reterritorialize unpacked history against

official historiography.

Kang’s intervention with the concept of con-temporaneity begins

with her early work, The Grandmother Tower (2011),

sculptural portraits of her grandmother (halmoni, in Korean). Kang utilizes her

own visual grammar to illustrate the very last moments of her grandmother – as

Kang mentioned, “scrawny yet beautiful” – whose personal memory embraced the

entire upheavals of the Korean modern period, from colonial to postcolonial

history. Based on her intimate conversations with and recollections of her grand-mother

– whose presence was so fragile that she was barely able to stand, yet who kept

her own dignity by smiling in front of her granddaughter like her last

hwajeontae – the work becomes an ontological skeleton of Kang’s artistic aims,

embodying time as flesh and blood. The vanishing presence of her grandmother

(halmoni) indicates not only the disappearance of premodernity to Kang, but

also the loss of vessels who can transmit memory from the past. This idea of

art as mnemonic device summons the very meaning of Korean modern history,

especially women’s lives. The grandmother aggrandizes her personal memory to

the official historiography, as Kang utilizes the demolished voices from the

past as the proof of modernity through the lens of halmoni’s perspective. The

Grandmother Tower is the prototype of Kang’s vision of affective

spatiotemporality, which spans her unique vocabularies of mora/jeong and

hwajeontae. Art as the mnemonic device of remembering, the essence of Kang’s

conceptual painting, becomes both a dialogic form and preliminary platform to

unearth the myriad forces behind dire issues of subjectivity in Korea, here

recreated through constitutive self-displacement and spectral variations in

artistic performativity.

1.While working on a series of true-view landscapes, Gyeomjae

painted the mountains by sitting outside and looking directly at scenery.

Gyeomjae engaged this true-view land-scape painting style almost two hundred

years before Europeans began painting en plein air.

2.Intermediality is a term used to define phenomena that appear or

may appear through the crossing of media borders. According to Werner Wolf, it

“can be applied, in a broad sense, to any phenomenon involving more than one

medium,” such as individual texts, films, performances, and/or popular culture.

Werner Wolf, The Musicalization of Fiction (Amsterdam: Brill Rodopi, 1999), 36.

3.Goryeosokyo, Goryeo gayo, and/or the Song of Goryeo was an oral

genre of Korean poetry, dating from the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). As with

other oral literatures, such as hyangga, which were written using Chi-nese

characters in a system known as hyangchal, the compo-sition of Goryeosokyo

became popular during the middle and the end of Goryeo Dynasty. Most of

Goryeosokyo was written in the Hangeul alphabet and orally transmitted in

Joseon Dynasty. The characteristic of Goryeo-sokyo is a refrain at the end of

each stanza that builds a tone or atmosphere by introducing a different melody.

4.Walter J. Ong, “Print, Space and Closure: Hearing- Dominance

Yields to Sight Dominance,” Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the

Word (London: Routledge, 1982/2002).

5.What is most interesting about Ong’s theory of secondary orality

is that it postulates that electronic media can extend place and time: “This

new orality has striking resemblances to the old in its participatory mystique,

its fostering of a communal sense, its concentration on the present moment, and

even its use of formulas. But it is essentially a more deliberate and

self-conscious orality, based permanently on the use of writing and print,

which are essential for the manufacture and operation of the equipment and for

its use as well.” Ong, Orality and Literacy, 133.

6.Ong, 136.

7.David Teh contemplated the origin of national tradition in Thai

contemporary art in a 2014 paper: “Art’s address to the past is always a double

movement, addressing two pasts: the past that may be its theme or referent; and

a past that’s immanent to its praxis.” David Teh, “La Fausse Monnaie: Tradition

as False Currency,” Tradition (Un)Realized, International Symposium (Seoul:

Arko Art Center, 2014), 115.

8.According to Foucault, the dispositif is not a technical

apparatus. Rather, it is a system of relations, such as discourses,

institutions, or philosophical and ethical statements, marking historical

moments that respond to an urgent need. See “The Confession of the Flesh”

(1977) in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, ed. Colin

Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 194–228.

9.Hwamunseok is an embroidered handwoven mat made with reed,

bulrush, or straw, combined with peony, plum patterns, and/ or tiger, dragon,

and phoenix shapes, from the time of the Shilla Dynasty (57 BCE–935 CE). In

Kang’s Black Mat Oriole, hwamunseok is a restricted site for the Chunaengmu

performance, where a dancer is allowed to perform for royalty.

10.Bak is a traditional percussive instrument used to announce a

transition to the prelude of ritual music in premiere court performances.

11.According to the Manual of Court Banquet (Sunjo gichuk-jinchan

uigwe, 純祖己丑進饌儀軌, 1848), the oldest documents providing

information about Chunaengmu, the dance has existed since 1649, but was revised

and perfected during Prince Hyomyeong’s tutelage. Moon Il-ji, “Ch’unaengjŏn (Nightingale Dance), a Korean Court Dance,” Yearbook for

Traditional Music, vol. 15 (East Asian Musics, 1983), 71–88.

12.Praised as “the flower of court dance,” Chunaengmu is the only

solo Korean court dance performance that includes choreographic patterns and

movements, such as gwagyosun (過橋仙), nakhwa

yusu (落花流水), daesu (擡袖), dosua

(掉袖兒), bansusubul (半垂手拂),

beonsu (飜袖), and hwajeontae (花前態) within six ja (尺, 자), a Korean unit of length (one ja is approximately 0.33 m, thus six

ja is equal to two square-meters).

13.Yeongsan hoesang is a Korean court music repertoire,

originating from Buddhist music, originally sung with seven words, as chanted

in the Buddha’s sermon. Pyeongjo hoesang is an alternative version of Yeongsan

hoesang, transposed four scales lower. Pyeongjo hoesang is used as

accompaniment to the court dance Chunaengmu and solo daegeum (large bamboo

trans-verse flute from traditional Korean music) performance.

14.Performers can dance on the hwamunseok without shoes, only if

wearing traditional socks called beoseon. In Black Mat Oriole, the performers

in both the installation and actual performance do not wear socks. Usually

dancers wear aengsam, a yellow costume, along with a headdress called jokduri,

specifically meant for female dancers.

15.Suki Seokyeong Kang, in conversation with Maria Lind, 2018

(p.193).

16.The sinking of MV Sewol, also referred to as the Sewol Ferry

Disaster, occurred on the morning of April 16, 2014. The disaster killed more

than 300 people, mostly high school students from the city of Ansan, who were

on a school field trip to Jeju Island. The tragedy is now seen as resulting

from a combination of the government’s lack of effort, eluding of

responsibility, and general mishandling of a very preventable event. The

disaster created an outrage in South Korea, with public candlelight vigils taking

place from 2014 to 2017, and created a demand for a special investigative law

to reveal and bring to justice parties responsible for the sequence that lead

to the sinking of the ferry.

17.Gilles Deleuze, Proust and Signs: The Complete Text

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1964/2003), 15. Deleuze explores

the system of signs via Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, through looking at

signs left by persons or events to explain how those memories interpret signs

creatively but inaccurately. One of Deleuze’s aims is to challenge the common

concept that involuntary memory and subjective association in interpretation.

18.“I created a video that animates the art and extends it to the

next page of the story. I hope this operates as a plat-form for the work, or

that it creates a space of possibility to embody personal thoughts and voices.

This is to point my work to where it stands now, its past and present, and its

potential to head to another place in the future.” Suki Seokyeong Kang, in

conversation, 155with Maria Lind, 2018 (p.199).

19.Kang’s conceptual painting in abstract grids and frames is

mobilized by a doubled spatio temporality of both past and present, where the

spectator and the sculptural presence interchange meanings and sign between the

contemporary and the archaic, and the transient and the eternal mode of

affective movements as the archives of future memory.

20.Giorgio Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?,” in What is an

Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Palo

Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009), 53.

21.During Japanese colonial occupation (1910–1945), all court

dances were banned. Only five court dances survived and were inherited until

now: Cheoyongmu, Pogurak, geommu, Mugo, and Chun aengmu. They were performed in

entertainment houses called Gyobang.

22.Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Post-coloniality and the Artifice of

History: Who Speaks for the Indian Past?,” Representations 37 (Oakland:

University of California Press, 1992), 1–26.

23.Hyunah Yang, “Finding the ‘Map of Memory’: Testimony of the

Japanese Military Sexual Slavery Survivors,” Positions 16.1 (Durham: Duke

University Press, 2008), 84.