“It is also well worth notice that, although

mourning involves grave departures from the normal attitude to life, it never

occurs to us to regard it as a pathological condition and to refer it to

medical treatment. We rely on its being overcome after a certain lapse of time,

and we look upon any interference with it as useless or even harmful.” — Sigmund Freud, Mourning and Melancholia, 1915.

1. Hello

Minae Kim greets you with a

friendly “hello,” but that is all she says. Other than “hello”(the title of this exhibition), the only messages from the artist

are the captions of the works, which do not even have conventional titles.

Instead, each work is assigned a serial number, along with a caption that dryly

and precisely conveys some basic details of the works, such as their material

and size. Assuming that the listed materials and dimensions correspond to the

actual works, these captions are little more than a tautology. Each caption

directly translates the physical properties of the work into letters and

numbers, rather than conveying a subjective message with new information or

meaning. Perhaps the serial numbers of the works (ranging from 1-1 to 5-1) are

a passcode that unlocks the principle behind the composition of the exhibition,

but if so, no additional clues are offered to help us decipher it. One cannot

help but feel a little embarrassed looking at a “table

of contents” that contains only the numbers of chapters

and subchapters. In any case, before closely examining the exhibition, the only

message from the artist is “Hello,” a casual greeting.

As we know, a greeting does not

contain any substantial meaning; it is just a signal of the beginning of a

certain relationship, without stipulating the nature or contents of that

relationship. No one can predict whether a relationship that begins with “hello” will progress into friendship or

catastrophe. Thus, even if a greeting was a message, it would be an empty

message, or “zero degrees of a message.” A greeting is simply a gesture of (re)confirming the formal

structure for a new or existing relationship. It is a moment of structural

recognition that creates the frame of the relationship before filling in the

contents. By the way, who exactly is Minae Kim greeting? With whom has she

decided to start a new relationship? In light of her previous works, we might

expect that the other party is the exhibition space itself. For the past ten

years, Kim has been presenting works with a sculptural methodology, savvily

acknowledging, exposing, and transforming the architectural structure of the

exhibition space. Only after greeting the architectural space of an exhibition

does she begin to conceive her works. However, her greeting does not stop

there. In direct response to the exhibition space, she installs sculptural

devices that act like parasites, changing the structure in some way. Then,

after setting the changed structure as a new default, she adroitly greets the

space anew with a “hello” in

order to pursue another sculptural intervention. With this in mind, the “table of contents” and serial numbers from

this exhibition might represent Kim’s attempt to give

this superimposed “hello” its

own order. Although the only message from the artist is “hello,” this message is repeated and

reiterated multiple times.

2. Manuscript Paper and Graph

Paper

In the beginning was “hello.” Minae Kim’s

world did not originate from nothing, but from setting a basic spatial default.

None of the spaces in her world can exist without spacing. Rather than a blank

piece of writing or drawing paper, her world is a piece of squared manuscript

paper, with lines and squares to guide penmanship. Even with no writing on it,

the surface has already been divided into hundreds of square units. Or perhaps

it is graph paper, with a space divided into millimeters, with no drawings or

graphs yet written on it. In her first solo exhibition 《Anonymous Scenes》 (2008), Minae Kim

presented her ‘Manuscript Paper Drawing’ series, which featured

writings on manuscript paper with some of the squares cut out or blacked out.

By concealing or removing the contents, Kim found an innovative way to evoke

the spatial structure that is presupposed by writing. On the other hand, Kim’s 2010 work Conundrum consisted of a large object resembling a

telescope, with a mirror and graph paper attached where the lens should have

been. Anyone who looked into the telescope expecting to see magnified objects

was surprised and perhaps frustrated to see graph paper instead. Rather than

presenting the enlarged shape of an object, the artist showed the implicit

grids that precede our perception of objects.

For Minae Kim, the architectural

space of a museum is like squared manuscript paper or graph paper. Prior to an

exhibition, she greets the empty space, which does not contain any artworks,

but has already been divided into various grids and dimensions. Before conceiving

her art and exhibition, she must first introduce herself to the architectural

structure—i.e., the walls, floor,

ceiling, windows, doors, stairs, lights, etc.—which she

views as a three-dimensional piece of graph paper. As opposed to the areas

where people typically congregate, Kim focuses more on the architectural

elements with highly functional purposes, such as hallways and staircases,

which tend to be the most overlooked parts of an exhibition space. She keeps

her eye on the blind spots that are easily ignored, despite their legitimate

role in dividing or connecting the space. Because they often go unnoticed at

the conscious level, these elements are like a frame that unconsciously limits

and guides human senses and movements. In Rooftoe (2011)

and A Set of Structures for White Cube (2012), Kim

installed prosthetic objects resembling crutches to support the ceiling and

stand in the corner of the space, respectively. For Black Box

Sculpture (2014), she placed the “alter

ego” of an escalator next to the original. By acting as

a parasite to these unconscious frames, she extends and replicates the overall

space in strange ways.

Minae Kim’s works stem from her recognition of various types of frames:

manuscript paper as the frame for writing, graph paper as the frame for

mathematics, and architecture as the frame for human life. At the individual

level, a frame is revealed in the habits that unconsciously define a person’s thoughts and actions, while at the social level, the frame takes

the form of collective habits, such as conventions and culture. At the level of

art, the frames are the institutions that monopolize aesthetic evaluations,

including art museums. By actively intervening with such frames, Minae Kim’s art reveals the personal habits, social conventions, and art

institutions that are hidden right in front of us. Slightly tweaking the gaps

in the rigid grids, she makes a gesture of resistance, evincing a spatial

metaphor for the duality of the self, the dialectic of society, and the fate of

the avant-garde, all of which are “parasites” on the frames that refine the attitude of compromise.

3. Through the Looking-Glass

Fittingly, for the 《Korea Artist Prize 2020》 exhibition,

the space that was allotted to Minae Kim includes part of Gallery 2, which

happens to contain a complex network of square units and grids that are much

more complex than the typical “white cube.” The space is divided into two sections with different heights by a

central wall, which is penetrated by three large hallways and the stairs

leading to the upper floor. Notably, these hallways and stairs are the parts of

the space that Minae Kim greets for the first time. Sitting in the exhibition

space like blocks that have been removed during a game of Jenga are three large

cubes that seem like they could fit into the three respective hallways. As a

result, the three hallways that visitors unconsciously presume as the default

of the museum space suddenly seem to have been artificially formed by separating

the three cubes from that middle wall. Meanwhile, the stairs, which are

temporarily blocked to restrict the traffic between Kim’s exhibition and the upper floor, are adorned with a red carpet, as

if welcoming attendees of a gala event. Perking up these peculiar conditions,

Billy Joel’s song The Stranger (1977)

is played. Finally, boxes of light that resemble elongated windows shine

diagonally on the walls of the stairs, running parallel to the steps.

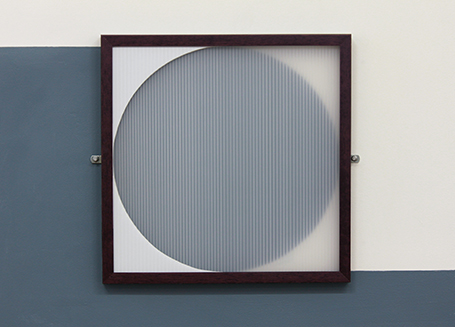

In her response to the space, Minae

Kim reflects various structures in unexpected ways, generating a type of “alter ego.” The result is a strange mirror

effect that does not provide a true reflection of the divided space. Indeed,

several of Kim’s previous works have incorporated

actual mirrors, including Continuous Reflection (2008),

which was presented at her first solo exhibition, and the aforementioned

Conundrum. In this exhibition, mirrors have been attached to the three cubes,

reflecting the hallway. Of course, every mirror serves to expand space, express

self-reflectivity, and juxtapose reality and illusion, but Kim’s use of mirrors should be understood from a broader perspective.

Indeed, her unique mirror effect does not even require real mirrors. She often

forces an object to confront its image, which has been conspicuously reversed

or altered in some special way. Through her command of this mirror effect, the

hallways are perceived as negative spaces, the inverse of the empirical cubes,

while the flesh of the stairs is separated, such that the frame(or bones) is

changed into a reflective window. Consequently, Kim’s

extraordinary mirror is both a mould and an X-ray.

In her third solo

exhibition, 《Black, Pink

Balls》 (2014), Minae Kim invited visitors to step

through the back of a mirror. In the gallery, the artist built another

architectural space with translucent fabric, filling it with some of her

earlier works that were separated from their original spatial contexts.

Twirling pink lights from inside cast shadows of the works on the translucent

fabric. Adding to the uncanny environment, the exhibition title and dates, the

name of the artist, and the warning “DO NOT ENTER” were all written on the fabric wall of the temporary structure, but

all of the words were flipped, like a mirror reflection. As a result, visitors

who bravely or blithely ignored the warning(“DO NOT

ENTER”) felt as if they were walking into the back of a

mirror. They then found themselves in a strange realm inhabited by the

parasitic sculptures by Minae Kim, which had become brazenly self-reliant after

shedding their original spatial context. In other words, Kim’s imaginary mirror, which people can enter at their own risk,

projects the shadows from the other side, rather than the images of the

external object.

A similar mirror effect is

achieved in 《1. 안녕하세요 2. Hello》. First, another diagonal box of

light resembling an elongated window appears on a wall of the space, acting as

a reversal diagonal of its counterpart above the stairs. Anyone sitting in

between these reversed windows has no way of knowing which side is the front or

back of the mirror. In addition, black contact paper that matches the width of

the red carpet extends obliquely on the floor, before extending vertically up

the side of an exhibited work, as if the shadow of the carpet was reflected by

the mirror in the wrong direction. The mirror effect extends to the handles on

the sides of the aforementioned cubes, which are symmetrically matched with

handles on opposing walls. Inverting the hierarchy of objects and space, Kim’s mirror effect disturbs the presumed coordinate axes of the

audience’s perception.

Matching—or mirroring—her emphasis on functional

architectural elements such as hallways and stairs, Minae Kim also pays special

attention to practical accessories like wheels and handles, which exist purely

as a means, not an end. Just as hallways and stairs exist as channels for

movement, rather than as independent destinations or points of departure,

wheels and handles serve solely to allow other objects to be moved. Again, such

objects may be seen as three-dimensional versions of the gridlines on manuscript

paper or graph paper. By imagining a displaced environment in which these

things do not function merely as tools, Minae Kim pulls them from the realm of

invisibility. For example, the wheels and handles on the three cubes, as well

as the handles on the walls, serve no ostensible purpose, and thus command

visitors’ attention and contemplation. In such ways,

Kim simultaneously raises awareness of useless tools and means without an end.

Throughout her career, she has continuously presented such functional objects

with no function, such as a telescope that does not magnify objects, pillars

that do not support the weight of a building, wheels that extend into the air,

windows and doors that cannot be opened, and stairs that cannot be climbed.

Such devices can be found

throughout this exhibition: useless red wheels, silhouettes of windows and

doors shallowly etched into the cubes, handles attached in random places, and a

red carpet(and its shadow) leading to nowhere. Such self-replication and self-retrospection

show that Minae Kim is greeting not only the exhibition space, but also

herself. Even while repeating her methodology, Kim persistently rethinks and

reconfirms her identity in visualizing the frames of a given space. Like the

skewed reflections in her works, she greets and faces her own image in a

narcissistic mirror effect.

Notably, however, these

narcissistic devices never devolve into pure self-attachment because the entity

that Kim aims to greet is not her isolated psychological self, but her

institutional identity as an artist. Kim is particularly interested in examining

the conditions of possibility of “artist” and “artwork,” which explains why Ai Weiwei is also summoned for reflection in

this exhibition. Prior to 《1. 안녕하세요 2. Hello》, this exhibition space housed Ai

Weiwei’s work Bombs, as part of the exhibition

Unflattening. Interestingly, the space still bears traces of Ai’s work, including torn images of bombs near the top of an interior

wall. Compelling Ai Weiwei to join her mirror play, Kim rejuvenated a

two-dimensional image from his work, dislocated from its context of an

exhibition about war, by turning it into a three- dimensional sculpture in the

center of the space. By appropriating the work of the Chinese artist as her

own, Kim reflects on her methodology of parasitic sculpture from a fundamental

point of view. Must an artist’s creativity depend on an

institutional frame? Can any work be independent from its spatial context? Can

a totally autonomous work exist?

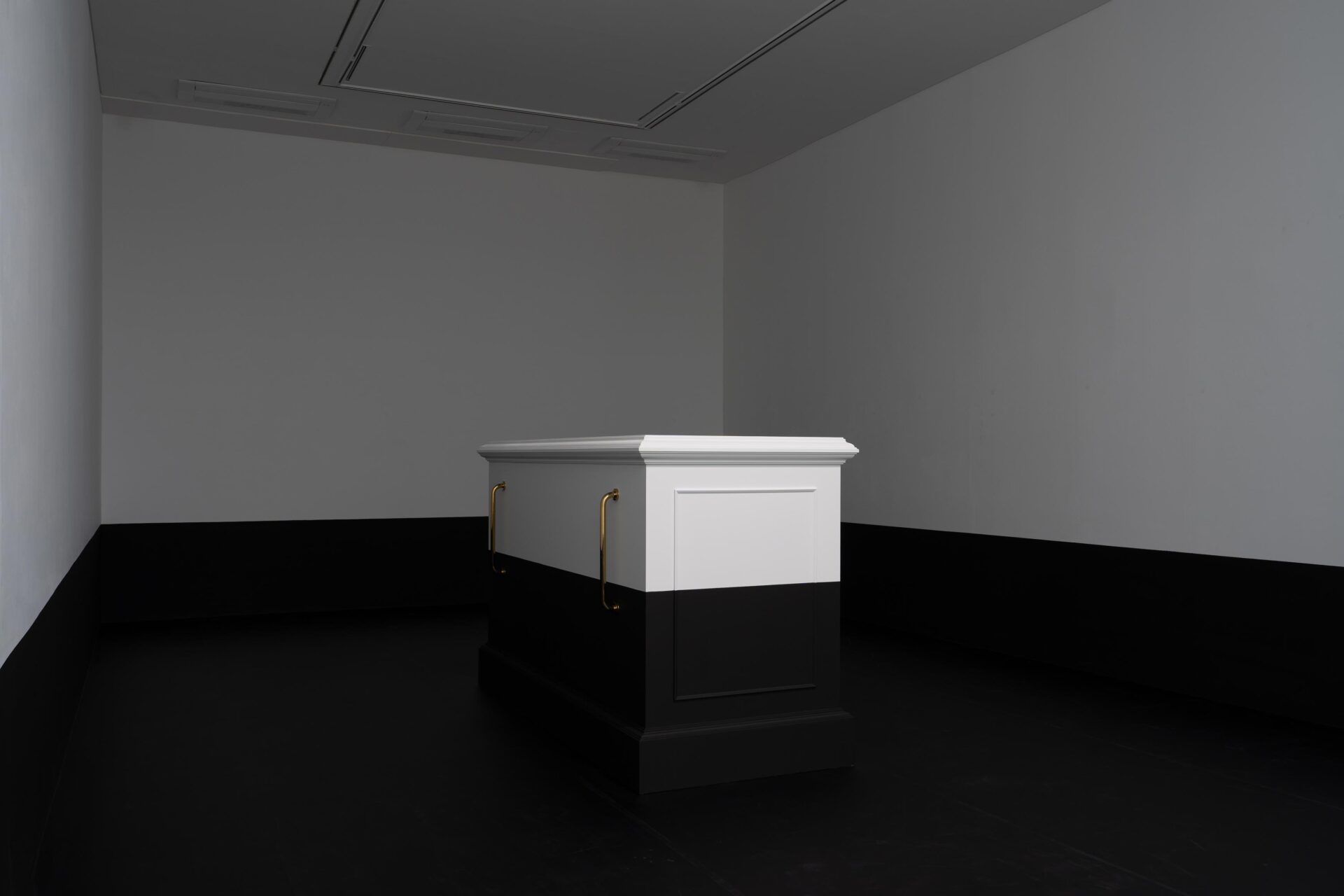

4. Greeting of Mourning

At first glance, 《1. 안녕하세요 2. Hello》 resembles

a retrospective of Minae Kim organized by the artist herself. Her

representative methodology of infesting the space with parasitic sculptures is

on full display, and many familiar motifs from her past works can be

identified, including useless wheels and handles, carpets and mirrors that

invade and disturb the space, and the incorporation of elements from the

previous exhibition in a given space. But this self- repetition and

self-retrospection should be understood not only as revealing the artist’s narcissism, but more importantly, as attempting to escape from it.

Rather than affirming her previous methodology, the current works provoke

rumination by instigating doubt. Her paradoxical retrospective is not intended

as a reunion, but as a farewell.

Although “hello” is a greeting, it also implies an

eventual goodbye, which exists like the shadow of every encounter. If you do

not have a farewell with someone, you cannot meet someone else. When a greeting

occurs on this side of the mirror, the farewell is simultaneously exchanged on

the other side of the mirror. In this exhibition, one of the three cubes

slightly differs from the other two, having one side that is shaped like the

front of an altar. Atop this cube are figures of three geese concealed beneath

a waterproof tarp. The presence of an altar with living organisms covered by a

sheet clearly signifies death. Moreover, the size and outline of the cube seem

to refer to Rodin’s La Porte de l’Enfer (The Gates of Hell). Similarly, the vertical figure

of the bomb based on the image from Ai Weiwei’s work

also looks like a monument to death. Perhaps acknowledging the award system of

the Korea Artist Prize, Kim also added a vain trophy made of crystal,

commemorating nothing, which stands on a vertical pedestal. Embodying the

inherent vacuousness of art awards, this trophy also acts as the period on a

sentence after a passion has been exhausted or a time period ends.

Tracing the origin of the death

and farewell themes brings us to a “funeral” associated with Kim’s aforementioned solo exhibition 《Black,

Pink Balls》. Describing this exhibition, Kim said, “The idea was to hold a funeral of sorts for my ‘site-specific’ works in the past, giving

them a space of their own. So I created a pseudo white cube, an inverted

gallery space where the viewers could not enter straight away.”1 In other words, she wished to

bury her parasitic sculptures, which lose their meaning outside of their

original space, on the other side of the mirror. Why did the artist decide to

say goodbye to her previous works? Perhaps her desire was related to the

inevitable nihilism of works that cannot exist outside of their spatial

context. The eulogy at this funeral might consist of nihilistic readings from

postmodernism, with its reactive and negative attitude against modernism’s primary thesis, i.e., the autonomy of art. If a sculptor’s fundamental impulse is to create something that stands upright on

its own, then Minae Kim can pronounce her will to realize free-standing

sculptures without going back to modernism.

But a funeral is only the

beginning of a goodbye, rather than the end. In the psychoanaly- tic sense, a

funeral is just the start of the work of mourning, which does not end until the

self is completely separated from the lost object of attachment. Thus, only

when you break up with goodbye is the goodbye complete. As such, this

exhibition is also a greeting of mourning, marking the beginning of a long,

laborious farewell for Minae Kim. This retrospective is paradoxical in the

sense that it seeks to prospect, and the vertical objects here are

contradictory monuments commemorating in order to forget.

5. Balls

Oscillating between retrospective

and prospective, oblivion and memory, Minae Kim’s work of mourning is carried out in a dualistic manner, maintaining

her site-specific methodology while indulging her impulse to build something

autonomous. The sculptural desire of the latter resonates through several

vertical objects in this exhibition. Next to the bombs borrowed from Ai Weiwei,

Minae Kim erected a pen of about the same size. By juxtaposing the distinctive

shapes of a pen and bombs, highlighting their similar forms, she seems to be

gauging the gap between a work that depends on its spatial context and a work

that is independent from it. Nearby is another sculptural object with jagged

edges. Containing sand, this object might be taken for a large flowerpot, but

its relationship with the space is ambiguous. At present, it is unclear whether

these objects will be able to maintain their vitality outside the exhibition

space.

All of this mourning began with

black, pink balls. The black and pink balls, which inspired the title of Kim’s 2014 exhibition, were actually balloons that she spontaneously

brought to her solo exhibition in London in 2013. These enigmatic balls, which

are neither self-reliant nor dependent on the surrounding space, triggered Minae

Kim’s work of mourning. They unfold the spectrum

between the nihilism of site-specific works and the idealism of autonomous

works. Scattered around the space of this exhibition are several chairs that

look like black balls, with round seats and no backs or armrests. From a

certain perspective, these black dots resemble oversized periods. The work of

mourning is the process of putting a period after goodbye, and Minae Kim has

added several periods to complete her goodbye to her parasitic sculptures.

Significantly, however, a group of periods instantly becomes an ellipsis,

signaling that Kim’s mourning remains in process. She

will continue to act as a parasite of architectural structures, individual

habits, social conventions, and art institutions, while at the same time

probing the possibilities of building something original and autonomous, constantly

questioning the conditions of possibility of the artist and artwork after both

modernism and postmodernism.

1 Point Counter Point, exh.

cat. (Seoul: Art Sonje Center, 2018), 60.