History of Modern and

Contemporary Sculpture in Korea by Choi Taeman (a rare book

worthy of that title) begins with Rainer Maria Rilke’s assertion that a sculpture is “an object

that could exist for itself alone.”1 Implying the desire for a specific yet universal type of

sculpture, born from the traditions of modern sculpture and the historical

conditions of Korea in the twentieth century, this declaration presents itself

as an axiom, commensurate with the solid status of sculpture at the turn of a

new century, when the themes that had been so eagerly explored in the expiring

century—from the identity of Korean art to the essence

of sculpture—seemed to have lost their gravitas. In

truth, however, this idea is not entirely self- evident in the way of

statements like “painting is a painting.” Whereas painting is posited as a medium in the strict sense that it

mediates between a painting hand and a seeing eye, sculpture is posited as the

perplexing task of manifesting “an object that could

exist for itself alone.” Simultaneously too vague and

too strict, this conception almost inevitably results in a self-aggrandizing

myth. Why should we strive to satisfy the questionable demand of sculpture to

this day? This problem is generally handled in one of two ways. The first way

is to make an object without calling it a sculpture. The second way is to make

objects according to your own definition of sculpture.

Minae Kim chose neither path. For

her, sculpture is like a ghost that cannot be eradicated, because it does not

exist in the first place. If sculpture is something that occupies space like

other objects but still looks distinctively self-sufficient and self-supporting,

then even a human body could qualify as sculpture. Thus, sculpture should have

a presence like humans, yet without being confused for a human. Discovering a

body that does not belong to us has been a recurring theme of sculpture.

Indeed, sculpture’s capacity for

objectifying our anxiety, illusions, curiosity, desire, and hatred for the

human body is one of the reasons that it has endured. But Minae Kim is not

stimulated by the reverberation between humans and objects, but rather by the

instability of the object itself, which loses its original identity by being

swept up in human instability. Through the idea of sculpture, ordinary objects

are suddenly seen as lacking sculptural properties, while objects claiming to

be sculpture are placed in a state of nervous judgment. What was I supposed to

be? What else could I have become? Exploring such existential questions of

things in a theatrical way, Minae Kim transforms sculptures into allegorical

objects.

Theater of Things That Seem Like

Something Else (But Are Not)

Allegories say one thing while

signifying something else, thus triggering a series of leaps with no end. When

sculpture becomes allegorical, it does not have to be taken a face value, even

when it seems to be grumbling about its own dilemma. As odd assemblages that

modulate or imitate something that already exists, most of Minae Kim’s works actively respond to the question, what else could I have

become? However, these objects do not ignore the question, what was I supposed

to be? Indeed, the latter question is directed not only at the sculptures

themselves, but also at the exhibition space and the visitors. Through the

repetition of these riddles, the entire venue of sculpture is surprisingly

transformed into a theatrical performance by a wandering troupe of objects. Not

being limited to human forms, the versatile players can easily be recast to

play any number of roles, not only as actors, but also as props or the stage

itself. However, given that they are constructed in accordance with the

specific context of the exhibition space, they must be repeatedly broken down

and rebuilt for the next performance. Thus, the objects are virtually consumed

as disposables.

The sculptural theater of Minae

Kim is operated by the dreams and passions of these objects. In 《Black, Pink Balls 》(2014), objects that

she had used or produced for previous exhibitions were surrounded by tents,

resembling an excavation of the tomb of an elephant. Pink lights twirled around

the space like the spirits of the objects resting their heavy bodies, or the flashing

lights of guard posts keeping them from crossing the line. The pink will-o’- wisps, which simultaneously illuminated and obscured the objects,

floated indifferently across the flustered audience, who were unsure where to

put their eyes and feet in relation to the tent, which was marked with a sign

that said “DO NOT ENTER.” In

their confusion about how to respond to this instruction, however, the audience

had already become part of the theater separating the theater from the viewing

area, the tent and lighting instead created a new space beyond the mirror,

which was almost identical to an exhibition gallery, but not quite. The

exhibition was adjourned by the objects, which seemed to reject their assigned

roles and positions. As if they were not yet ready, or had been ready a long

time ago, the objects met people with disinterest, as if audience had arrived

at the wrong time.

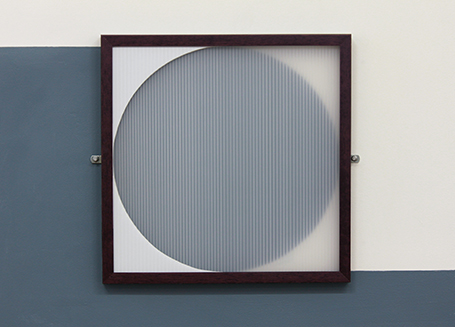

Refusing to be passively placed

in a space to be compared to other objects, Minae Kim’s objects reject the general order both of objects and of space.

Through this shared orientation, they selectively renovate whatever space they

happen to occupy, becoming semi-architectural performers that move through the

gaps between objects and spaces, as if demonstrating the route for evacuation

or attack. In fact, the objects themselves do not actually move. The only

kinetic element is the lights, which apply silent pressure to the objects,

emphasizing their inactivity. In 《GIROGI 》

(2018, meaning “wild geese”), the gallery was lit by rotating lights that seemed to have caused

all of the objects to disappear, with only the sound of flapping wings

remaining. As if to commemorate the missing objects, images of plump birds

embossed on the walls seemed to move ever so slightly, although that was

obviously impossible. In such ways, Minae Kim’s theater

stages the almost hopeless dream of things that become what they are not, elevating

to a higher plane. Their arrested actions unfold like a slapstick comedy

performed with a serious expression. In trying to assume the status of art,

they continually guess wrong, like a comedian who cannot find the keyhole,

trying one spot after another, never realizing that the object in his hand is

not even a key.

Although the gestures of these

objects inevitably overlap with images of the artist who manages them, they are

not anthropomorphized. In fact, they resemble humans by deviating from the idea

of being human. What appears and disappears in the space is not a body with a

face that expresses itself, but rather a partial object that uses the space

itself as its body, like a bizarre crutch. Indeed, Minae Kim once made a wooden

structure that looked like three connected crutches, which she called Freestanding

Sculpture (2012). The crutches, which are artificial limbs that

cannot stand on their own, become a self-reliant structure, supporting one

another. Losing their original function of supporting a person’s movement, they became a dilapidated monument to themselves. In an

effort to assert their self-reliance, the crutches keep changing their

appearance, from a table to a pillar, a pedestal, and even a mop, but these

deficient attempts at rehabilitation only serve to emphasize their uselessness.

Sculpturally defective objects often get stuck while trying to figure out how

to transition to the correct state. A crutch for a wheel(rather than a foot)

might take a hilarious fall, causing laughter. But the next scene, in which the

crutch prevents another crutch from falling, is not the least bit funny.

When History Becomes Future

Where can a theater of objects

go, when the objects refuse to comply with the ethics of everyday goods,

sculptural conventions, traffic regulations, or architectural rationale? One

imminent possibility is to become history. While this might sound boring and

self-evident, the path to such a future is unexpectedly invisible. What type of

vehicle is required to protect the objects as a collection of memory as they

seek asylum in the future? Where would this lead them? One possible answer

is Sculpture on Wheels (2018), another type of

self-monument that imprints objects’ irregular orbits around the idea of sculpture. Notably, this work

derived directly from Kim’s previous installation A

Set of Structures for White Cube (2012), which consisted of

wheeled crutches that could only stand by being propped up in the corners of

the gallery. For the later work, Kim created a new cross-shaped prosthetic that

enabled the imperfect single legs to lean on one another, before turning their

self-supporting assemblage into a transparent plastic sculpture. While the

original structure remained in ambiguous form, with only the red wheels

retaining their conventional function, the resulting object had a furtive

mobility, allowing it to merge with any surroundings, or even to make an

escape.

Notably, this work was produced

as part of a special program in which artists were invited to renovate and

re-install one of their previous works from the museum’s collection.2 The original work was in storage,

having already been absorbed into the government- managed history. With the

help of Minae Kim, however, it briefly escaped that history, allowing her to

make a plastic copy. But this newly materialized afterimage was quickly

ingested back into the museum system, with a new set of memories inscribed in

the meantime, like a tattoo. It is now an unnamed object that stands and

partially blocks the right entrance of Kim’s exhibition

for the Korea Artist Prize. Every object in this exhibition has erased its own

name and now joins in a new chorus of greetings, like an ensemble singing in

the round. Reflecting the given space and bending one another, they oppose the

gravity of the art museum as mausoleum. The space allotted to Kim for this

exhibition included the stairwell between the ground floor and the lower level,

with traffic between the two floors being restricted so as not to disrupt the

permanent exhibition upstairs. Kim decorated the dead end of the stairway with

a red carpet cut in the middle, accompanied by an old song that sounds somewhat

sinister. In this area, where the evacuation route has been blocked, the play

of objects resumes.

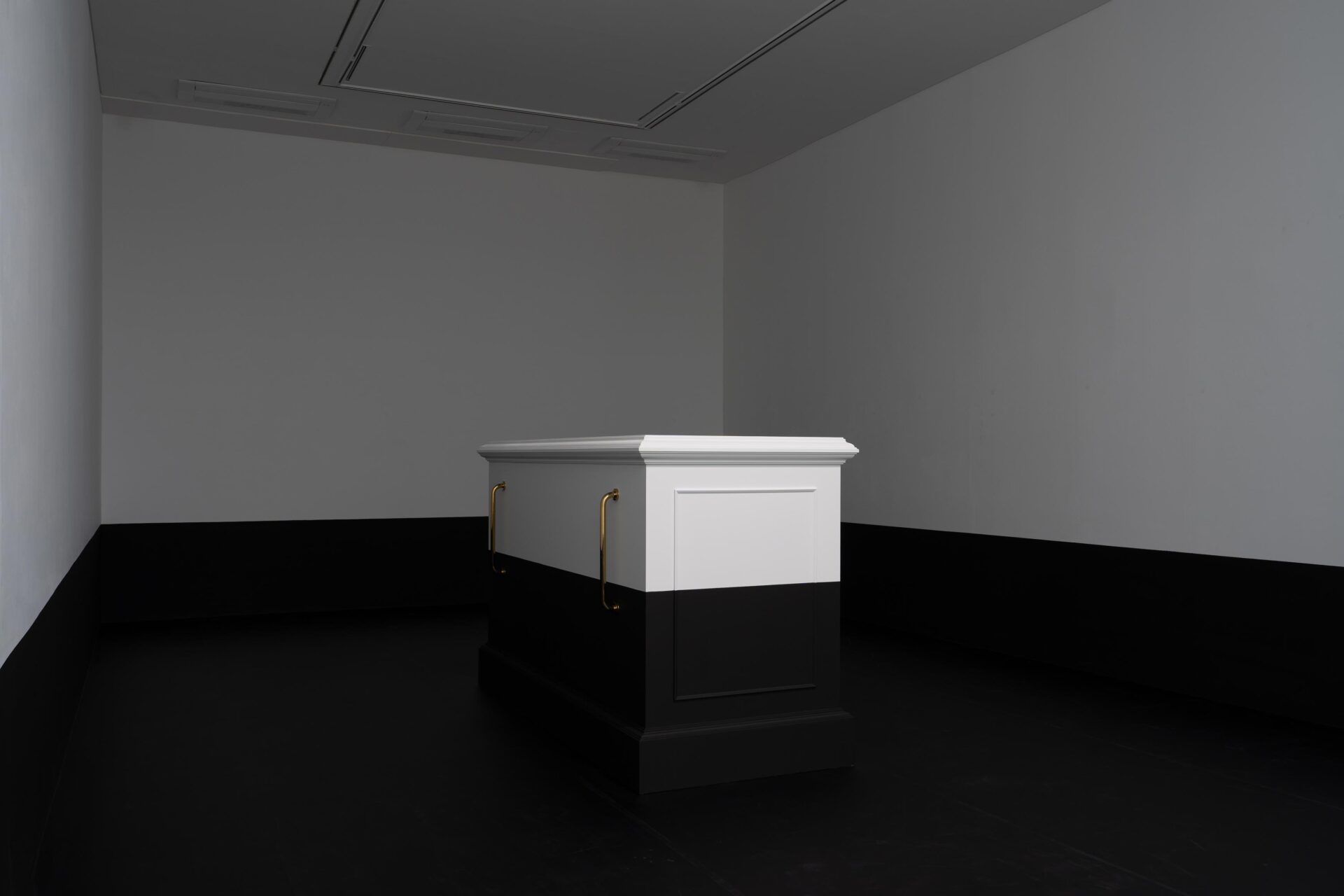

First, three cubes have broken

loose from the stairwell, which has now become useless. The cubes are modeled

after the three entrances connected to this stairwell, thus representing a

life-size sample of the architectural space of the museum and an extra

component that changes the space. Equipped with handles and wheels that are

unlikely to be actually used, these cubes claim to be mobile, but they merely

confuse the audience by obstructing or reflecting the surroundings within

mirrors or white surfaces. By disrupting the gaze and movement that the

museum naturally imposes, this sabotage temporarily neutralizes the invisible

boundaries distinguishing what should be seen from what need not be seen. In

this renovated space, other objects come in, one after another, until it

becomes difficult to tell the featured works from supplementary items either

assisting or hindering the exhibition. Some objects that take the stage

initially seem to be imitating something else, only to look clownish when the

association ultimately fails. The performance does not seem to follow any

predetermined script. Instead, each set of loosely bound objects around the

three cubes acts like the stage curtain of a play.

Like the three ghosts from A

Christmas Carol, the objects in this exhibition seem to act out

situations that either have happened in the past or could happen in the future.

In a way that diverges from the usual history of art, they represent the

fragments of collective memory shared by objects, with the museum as their

destination. Rather than certain objects going through certain situations, they

represent patterns in the lifetime of objects that were specifically made for

an art exhibition. Reenacting the collective memory, the objects examine the

conditions under which the repetitions occur, as well as irregular phenomena

that could emerge in the process. The objects ask questions, like how was I

made? What can I identify and compare myself to? What shall I become? Through

such questions, the objects transition from competitive relationships, in which

they desperately flaunt themselves, to cooperative relationships that explore

their shared destiny. If this transition ultimately leads to sculpture, it

might be valid not as an ideal to be blindly pursued or discarded, but as a

catalyst for inducing the unexpected resurrection of objects.

Reversing Hell

Through the left entrance that

leads to the stairwell, the first cube appears. A tall box is decorated with

hanging bands of gray adhesive, imitating the red carpet, and coated with a

layer of glossy paint. Near the box is a pair of open paint cans, with a brush

still inserted. Reminding us of the many objects inside a museum that are not

considered to be art, this plywood structure is built in the manner of a

freestanding display wall or pedestal, although it is too tall and thick to

serve either purpose. Interestingly, these large dimensions, which prevent the

box from serving a practical function, seem to have been made to suit the high,

wide space of the museum. It must have been constructed in this very space, and

will likely be dismantled here when the exhibition is over. Although the box

succeeds in visualizing itself as a self-monument, it ultimately fails to save

itself, and is thus relegated to become a futile memorial to the exhibition

objects that are waiting to be taken apart.

The second cube and its

derivatives are scattered near the central entrance, passing under the

stairwell. The cube is about the same size as a small studio apartment, as

suggested by the slight indentations indicating the possible positions of doors

and windows. While much larger than a person, the cube is still dwarfed by the

high ceiling of the gallery. As a conspicuous criterion showing the difference

in scale between a museum and a standard living space, this white cube reminds

us that the objects here are larger than they seem. Imagining what it could be

in reality, the cube changes its appearance to a low platform with seats and an

artificial lawn. Even so, the space is probably too small to accommodate a

group of people chatting or playing together. The relative sense of size

between art and reality continues to fluctuate. The righteous objects of the

artist are too big to enter the house, but too small to change the world. In

the end, they remain materialized signs representing something other than themselves.

Finally, in the extension of the

right entrance, there is the third cube, which is the largest and most daunting

of the three. Adorned with decorative molding and bearing three shapes draped

with loose grey cloth, it looks like the pedestal of a statue prior to the

unveiling. The shapes appear to be birds that are about to take flight in three

different directions. Of course, we know that they cannot fly away, even if the

cloth is removed. As an altar for wild geese that cannot fly, it corresponds to

the transparent eagle trophy on the opposite side of the gallery, thus

repeating the symbols of art and power that are endlessly reproduced and the

self-representation of art, as shown in Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1968– 1972) by Marcel Broodthaers. However, when approached purely as an

image, before the symbol, the three flightless birds looking down from a high

altar recall the three spirits with their heads lowered atop Auguste Rodin’s La Porte de l’Enfer (1880–1917). They dance atop the entrance to another world, but the

entrance, which does not open or close, is not actually a door, but a cluster

of objects.

According to Alenka Zupančič, tragedy and comedy are opposing

strategies for facing the human condition; while tragedy internalizes

unresolvable intervals between the infinite and finite as painful

self-destruction, comedy extends life by externalizing the indestructible

vanity of human beings.3 What happens to those who fail to

become what they are supposed to become? They go to hell. The wild geese ask, “Is this hell?” The audience, on the other

hand, asks, are the wild geese immortalized as tragic subjects who inevitably

fail in their pursuit of their ideals? Or are they ineradicable as comic

objects that boast as if they truly exist on another level? Instead of a door

that does not open, the altar to the wild geese lights up the exhibition space

with a large mirror. The space beyond the mirror reflects a series of illogical

images derived from the artist’s previous works and

past exhibitions in that space. Fortunately, on a clear day after the pandemic

has lessened, the blue sky and people passing by could also be seen. We are

here at last.

1 Choi Taeman, History of

Modern and Contemporary Sculpture in Korea (Seoul: Art Books, 2007), 15.

Quotation taken from Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, trans. Jessie

Lemont and Hans Trausil(New York: Sunwise Turn Inc., 1919).

2 For the

exhibition Extended Manual (Nam-Seoul Museum of Art, 2018–2019).

3 Alenka Zupančič, The

Odd One In: On Comedy (Cambridge, London: MIT Press, 2008), 53–58.