Body as Arrangement and Function

Sculpture is tied to the body in

Yoon’s work, not in their superficial similitude but

in their functionality, like organisms. Although her objects— ranging from spherical, cubic, conic, and elongated to thorny—derive from the body in one way or the other, their association with

the body has less to do with their shape or appearance than

processual elements, such as the role of the mother mold in the casting, or

certain material properties like responsiveness to the change in temperature,

moisture level, tension, etc. Some of her sculptures are used to wrap other

objects like skin or provide support like muscle or skeleton, while others

spill out the content with which they have been filled in like digestion. Yoon’s approach to the body in her practice differs, however, from

attributing human form to abstract shapes. It is rather the case where the

association with the body is found in the moment of figuration that consists of

gesture, motionlessness, touch, and movement, in all their interconnectedness.

Yoon’s work raises the question of what the body is. According to Butler,

the individual and biological body emerges in the moment of public and

political negotiation:

…could we not argue, with Bruno Latour and

Isabelle Stengers, that negotiating the sphere of appearance is a biological

thing to do, since there is no way of navigating an environment or procuring

food without appearing bodily in the world, and there is no escape from the

vulnerability and mobility that appearing in the world implies? In other words,

is appearance not a necessarily morphological moment where the body appears,

and not only in order to speak and act, but also to suffer and to move, to engage

others bodies, to negotiate an environment on which one depends?4

The pandemic was yet another

reminder of what it meant to come in contact with and engage other bodies. At

the same time, it has also provided an opportunity for Yoon to reexamine the

boundaries and vulnerabilities of the body in her work, which has hitherto

foregrounded the structure of sacrifice and interdependence. Although the

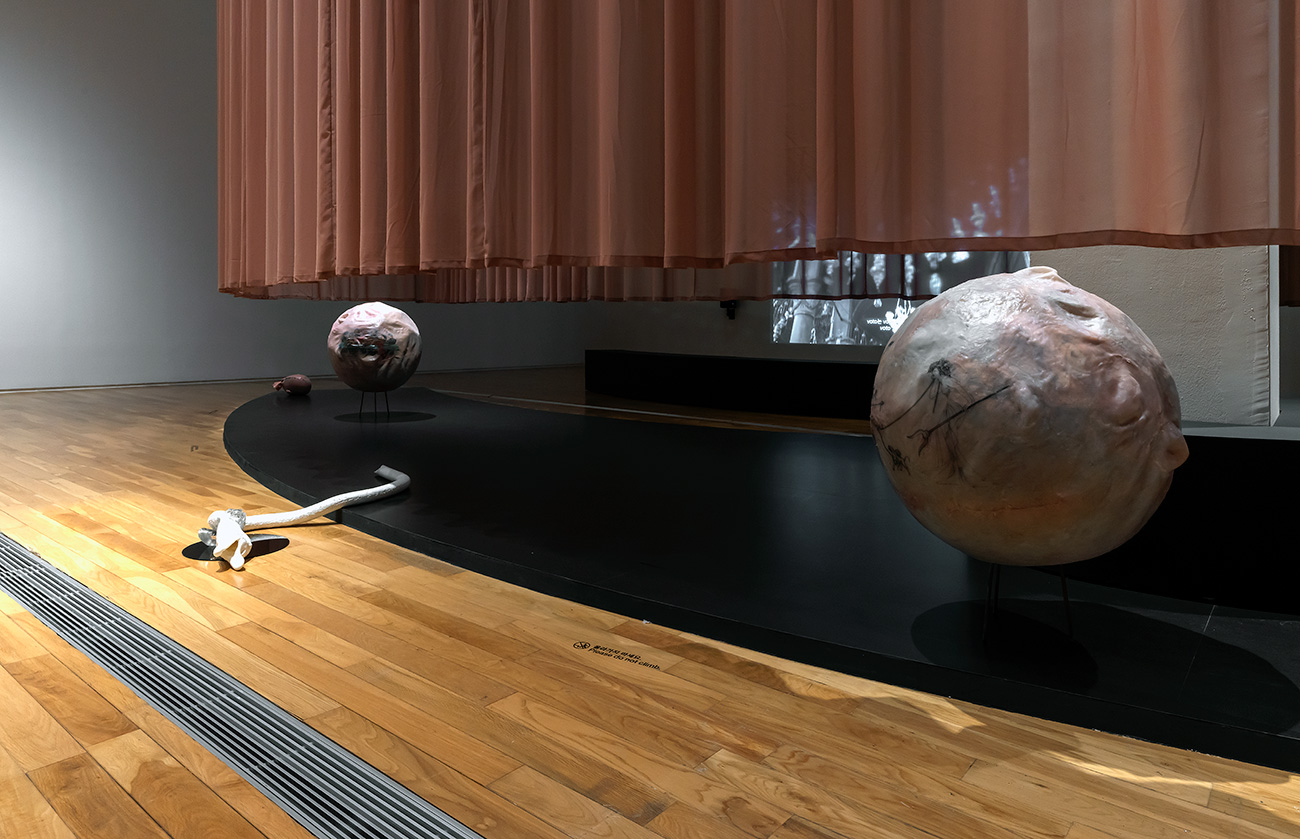

motifs of body mass and human skin have been implemented variously in That

that is is that that is not is not is that it it is (2016), No

Planar Figure of Sphere_ (2018), and Leda and the

Swan (2019), it is in the ‘Yellow Blues‘ series (2021)

where the use of silicone stands out the most. An oft used material for plastic

surgery, silicone boasts likeness to the human skin. It is temperature

sensitive and, once cured, comes to possess great elasticity and resilience.

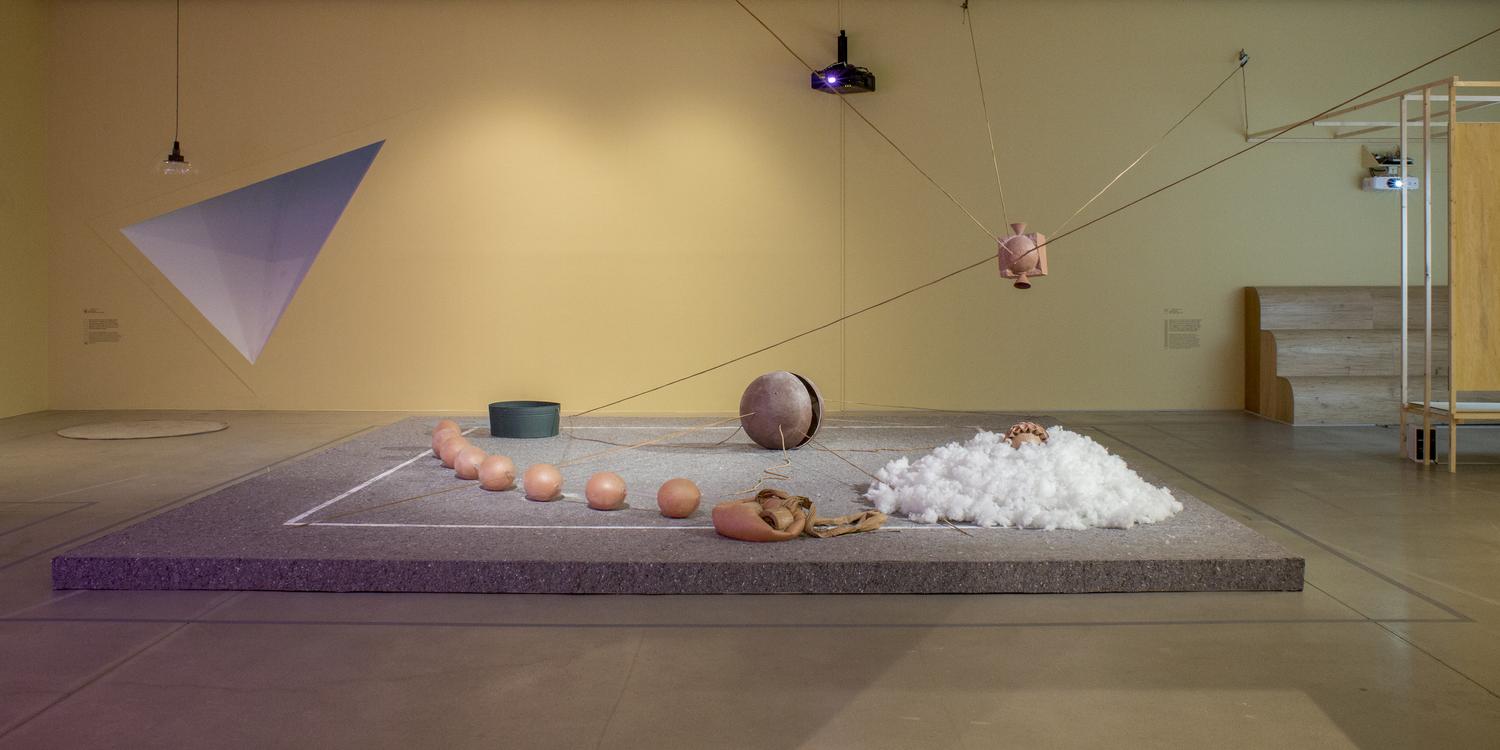

For the Young Korean Artists 2021 exhibition at the Gwacheon branch

of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Yoon presented a number

of sculptures in the ‘Yellow Blues_’ series where the plasticity of

silicone stood out: three yellow spherical objects with varying degrees of

hardness embracing one another, yellow balls in the size of a ping-pong ball

that were stacked up like a pyramid, a large sphere bound so tightly by yellow

ropes that its surface broke off. No longer bound by wires like in the previous

work, these sculptures were placed apart from one another like an archipelago.

In the corner of the exhibition space lay a cast of an arm from the elbow down,

where the hand remained open as if trying to catch snow or falling leaves. A

black mirror hung in the air reflected all other sculptures in silence,

contributing to the almost lyric quality of the exhibition. Almost all of them

were titled Yellow Blues_, which echoes Yoon’s attempt to address the state of self-consciousness—partly by referring to Agatha Christie’s ‘Absent

in the Spring’—where the person chews over one’s past actions and utterances during the times of isolation prompted

by the pandemic.

Yoon presents the same set of

themes with a more theatrical quality in her solo exhibition at One and J.

Gallery in the same year. A head swollen like a balloon, The

Absent Body: A Motherless Mold and a Face(s) is laid on the

floor, where the only trace of facial features in this sculpture is the

peculiar shape of the ear. Yoon works consciously with the notion of body mass

in this series: the six sculptures behind the dull apricot curtain, all of

which are painted in black, share the same volume of 65,416 cm3 , but vary in

shape, ranging from sphere, tetrahedron, cube to pentagrammic prism and

heart-shaped pillar. These metal sculptures are painted with special acrylic

pigment that absorbs 99.4% of the light, which creates a depthless void that

eliminates a sense of volume, appearing almost two-dimension.

Three-dimensionality is intimated by the silicone wrappings that have been cast

from each of the six sculptures. Their wrappings, however, are swapped: The

silicone “skin” of the pentagrammic prism is put like a cape on the heart-shaped

pillar, and the apex of the tetrahedron has pierced the skin of the

heart-shaped pillar that it is wrapped around; a sphere inside the tetrahedron

wrapping seems as if it have pinnaes. Would it be plausible to claim that they

are wearing other’s skin, which, by extension, alludes

to a process by which to attain ideal selfhood?

The plasticity of silicone in

Yoon’s work lays bare not only the border and

vulnerability of the body but also their malleability and the associated

feelings of hope, despair, and distress. Not only is the skin a volatile zone

of pain and pleasure but it also serves as a tangent of difference,

discrimination, contamination, and contempt. It is the border between self and

the outside world, a psychological wrapping that gives rise to ego through the

abundant sensorial correspondences it affords. Psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu

writes:

The skin…is superficial and profound. It is truthful and deceptive. It

regenerates, yet is always drying out. It is elastic, yet a piece of skin cut

out of the whole will shrink substantially. It provokes libidinal investments

that are as often narcissistic as sexual. It is the seat of well-being and

seduction. It provides us with pains as well as pleasures.5

Wishing You Well

As evident in the ‘Yellow

Blues_’ series where “body mass” manifests in varying geometric forms, the resemblance of the body

in Yoon’s sculptures is not restricted to that of the

morphological or the functional. She has expressed her wish to “express corporeality only with geometric forms,”6 where the body is abstracted in

terms of volume. Volume is a geometric abstraction of space taken up by an

object, and, therefore, has no form, premised on neither specificity nor

identity. Such brings to mind the American minimalist sculptors who have

produced cubes or other polyhedrons the size of the human body. When George

Didi-Huberman examines “anthropomorphism” in Tony Smith’s ‘Die’, along with

other minimalist sculptures, as a performative moment in which we are reminded

of our deep-seated anthropomorphizing impulse,7 he claims that

simple forms in the size of the human body often evoke an ancient monolith or

sarcophagus. Such an evocation has less to do with anthropomorphism than the

amorphous geometric resemblance, the silent void and the “votive quasi-portrait”8 in which we, to our own anxiety, find the resemblance to and

the absence of ourselves.

Yoon’s “quasi-portraits”

likewise carry semblance and absence, which allows serial emergence of beings

that are anonymous yet implicated in each other, more so than the dialectics of

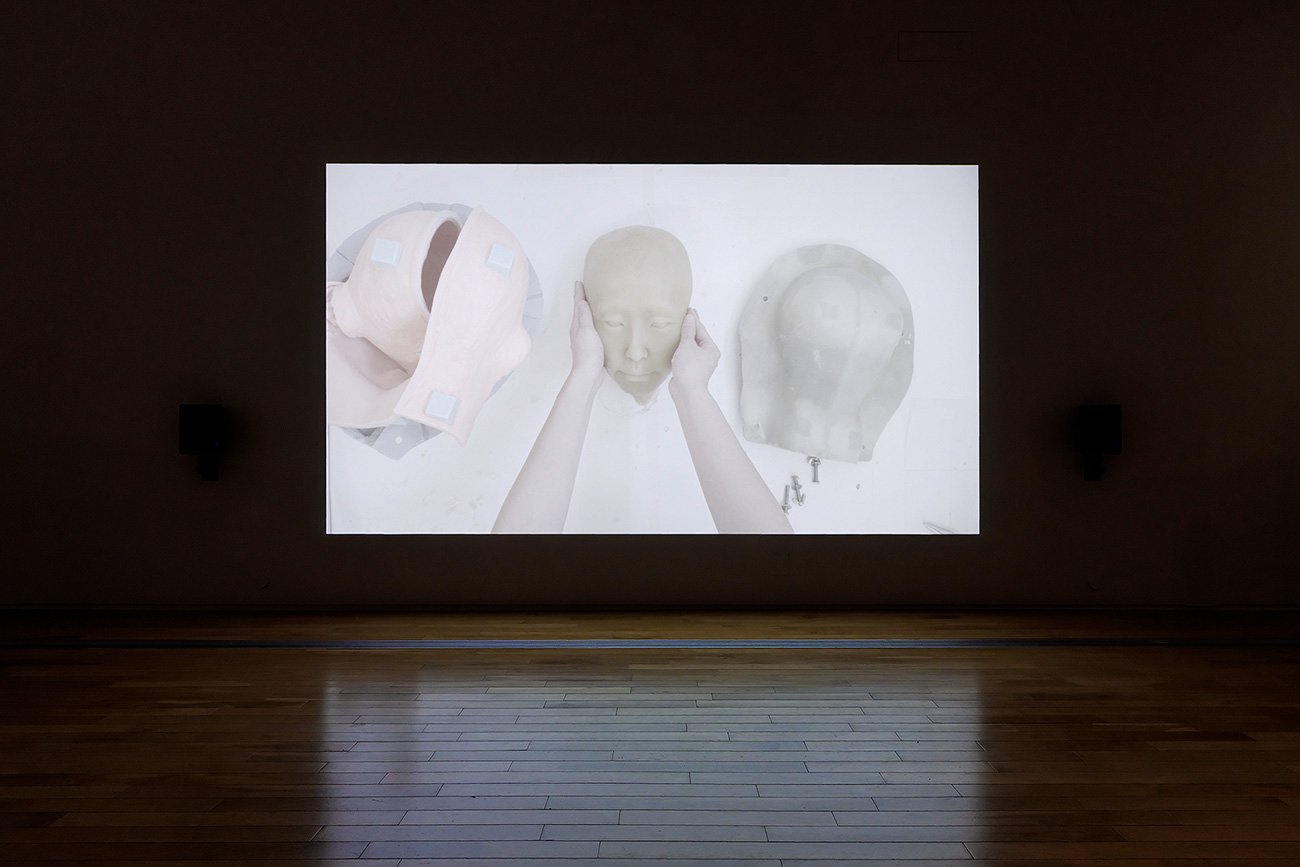

life and death taken up by the minimalist sculptures. Her most recent

work, Just One Head (2024), is a votive offering

that embodies the well-wishes from her close friends who speak and write in

English, Spanish, French, and Greek. Yoon records their voices onto wax

cylinders with an Edison phonograph, which she then melts and recasts into her

own face. The well-wishes uttered in different languages are reified and

embodied. The phonographic recordings have been digitally converted before

(re)casting, which emanate, almost like an echo, from the altar.

The ex-votos or votive

offerings in the form of the human body have various origins, which usually lie

outside the purview of the discipline of art history. According to

Didi-Huberman, most of ex-votos in Medieval Europe were wax casts of either

body parts afflicted by illness or prosthetics associated with such illness.

While they were offered for cure or as a token of gratitude for the cure, they

were also a physical manifestation of aftereffect, a relic of an ordeal. These

artifacts, according to Didi-Huberman, pass from the magic of contagion so

frequently invoked in religious healing—as evident in Mark 5:28, “If I just touch

his clothes, I will be healed”—to the “imitative magic” that constitutes the power

of resemblance. The wax is attributed with the power to extend the time of the

wish, and changes when the wish changes. The wax serves multiple functions,

and, with even greater plasticity than silicone, constantly reappears in new

organic fixations. Wax “is charged with representing,

on one hand, and warding off, on the other”, the

symptom of illness. Seen in this light, wax is likened to our flesh, constantly

replaced and regenerated through imitation as well as contagion.

Beeswax, along with silicone, has

been the staple material in Yoon’s practice. In the Yellow Blues_ exhibition, a yellow sphere

wrapped in a wire mesh hangs above a candle cube placed on a black reflective

surface. The bottom of the sphere, made of beeswax, is burned and hollowed,

from which the melted wax drips, collects in the empty tin box beneath it, and

hardens into a candle. While the work also appears to be another allegory of

sacrifice, it demonstrates, above all, the malleability and organic quality of

beeswax—which issues from the bodies of bees—and therefore the workings of flesh. It represents the extension—however meager—of space and time of the wish

held within the finitude of our bodies. The gesture made here is far from that

of permanence or transcendence: There is always some loss when the wax melts

and is recast, and the yellowness of the face, a votive offering made of

beeswax, will fade over time.

The tattered fate of our bodies

and objects, which are ever-changing but ultimately finite organisms, contrasts

sharply with the celebrated permanence of today’s digital media. Yoon’s sculptures present

the fragility of flesh and finitude of life through the act of making

sculpture, including its techniques and mechanics. Above all, her work shows

the embodiment of wishes for each other’s well-being,

which renders visible the public corporeality that bears the imprint of the

pain and sufferings of life. The so-called “five

viscera and six bowels” in East Asian medicine are not

only vital internal organs of the body but they are also symbolic and

indicative sites of suffering. are imprinted. The traces of pain and suffering

accumulate in and are etched onto the body over time, unbeknownst to the afflicted

and unlike a sudden blow, in spite of which the viscera constantly bring us

back to life. “There was a time when, not

knowing how to live, I took out my entrails to make a net.” (2024) is a net of prayer, a net of consecration, which

the artist has spent a long time sewing, weaving, painting, and drying by hand

for this exhibition. It is both an artifact of an ordeal and a portrait of a

massive prayer text, tightly woven and spread out before us.

1. “Space for an ear” is a phrase taken from the

statement for Jiyoung Yoon’s work Wooden Cube,

approx.15cm in Side Length, Became a Plaster Cube in which Something’s Negatives are Hidden (2018).

2. Judith Butler, Frames of

War: When Is Life Grievable? (London, New York: Verso, 2009), p. 19.

3. Jiyoung Yoon, The artist’s note.

4. Judith Butler, “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge

MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 87.

5. Didier Anzieu, The

Skin-Ego, trans. Naomi Segal (London: Karnac Books, 2016), 19.

6. Jiyoung Yoon, In a

conversation with the artist (September 2024).

7. This is explored in detail in

the following article by Nara Lee, which focuses on

Kim Minae’s sculptures. Nara Lee, “Image Anthropology and Contemporary Art: Image and Death ⓶ – Objects of Death, Places of Death: Renaissance, Minimalism, Kim

Minae,” Art World, December 2018 issue, pp.

144–149.

8. Didi-Huberman states that the

cubes, comparable in size to the human body and referred to as anthropomorphic

by Michael Fried, are images rich with formless figurative virtuality—what we might call “ancestral likeness.” According to him, this likeness, dedicated to dissimilarity,

rhythmically holds and spits out images of life and death before us. Georges

Didi-Huberman, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (Paris: Les

Éditions de Minuit, 1992), 94.