Inside and Out

In the work of Jiyoung Yoon, two different horizons intersect with

equal weight. One is a critical thematic stance that originates with her

personal experiences and awareness and that connects with social attitudes. The

other involves conceptual ideas about material that arise from her

understanding and interpretation of sculpture’s visual aspects. The work that results from this shows no direct

indicators of social or political incidents. At their simplest level, we see

objects designed in sensory ways; at a more complex level, we find what appears

to be a meta-discourse on the sculpture medium. Often, this is where the

interpretation of her work stops. Indeed, the history of modern art is one in

which medium-related discourse has taken place autonomously. Contemporary art

in a context in which art has separately emerged as a form of social practice

that is not afraid to intervene. When things exist in between or outside the

two, they can often be regarded as personal or abstract. Turning attention back

to Jiyoung Yoon’s work, we see how it attempts to

transcend this either-or approach to art’s social

nature. The personal is presented as something social rather than strictly

private, and interdependent structures emerge in the seemingly autonomous.

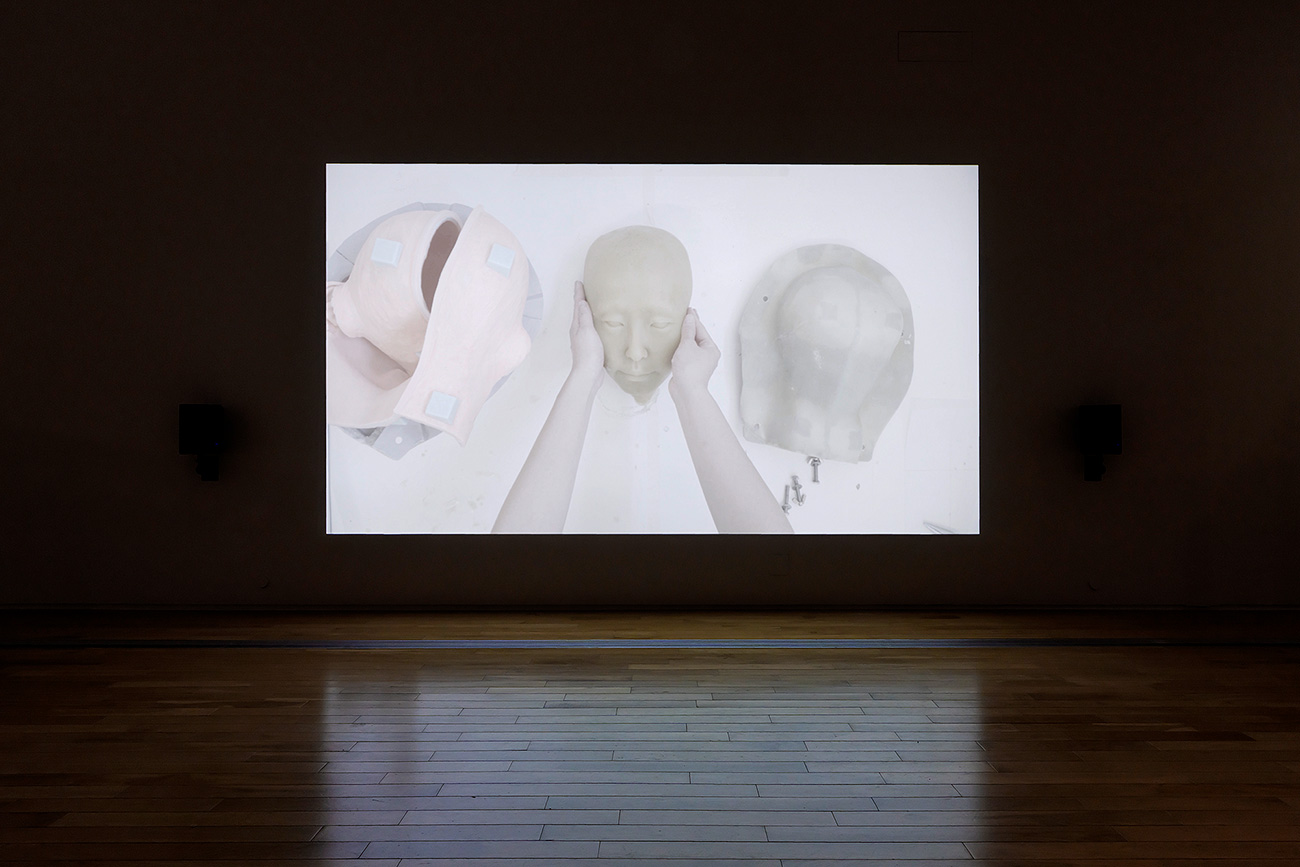

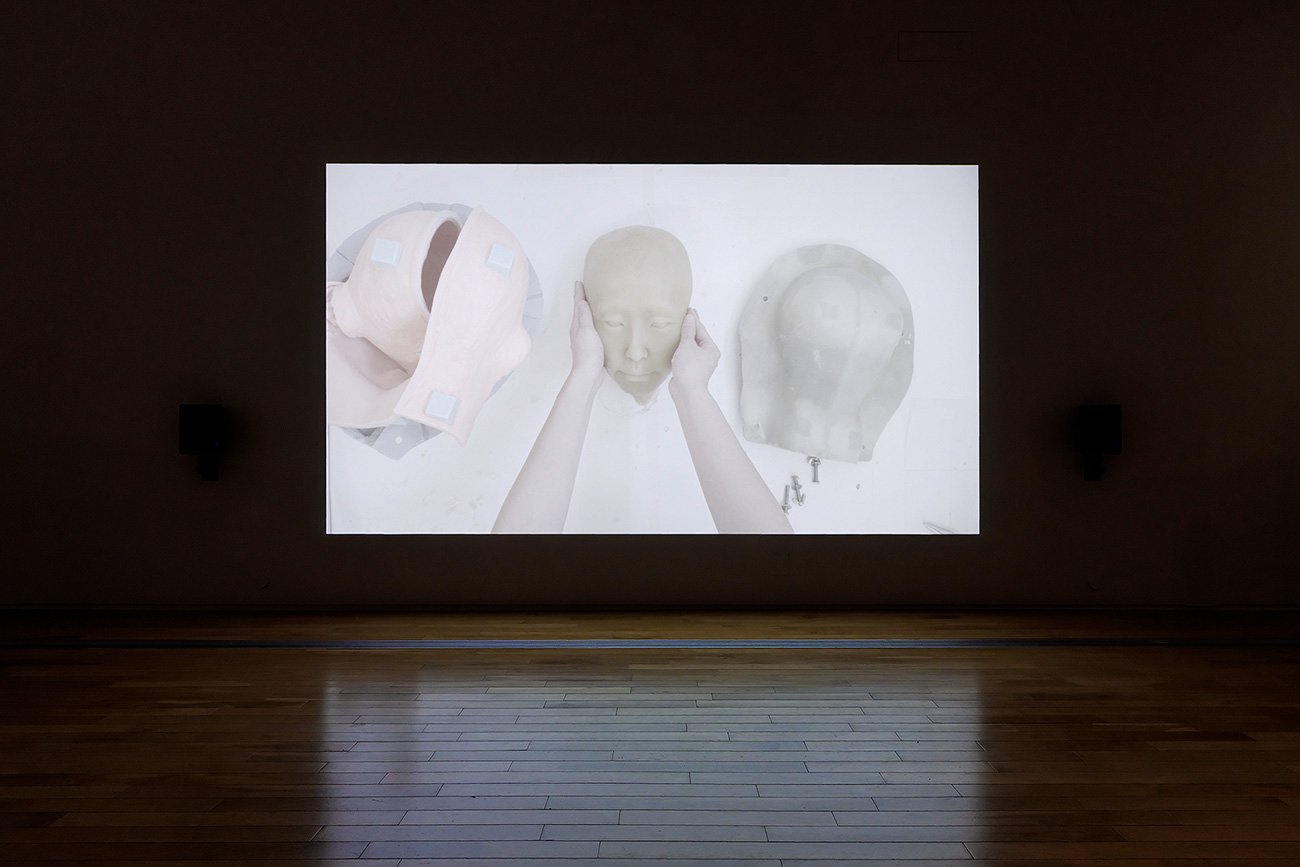

In her process of considering the invisible structures of

incidents and the relationship between their inner and outer aspects, Yoon has

appropriated mold-making as a crucial element of sculpture. A single concrete

scene: in 2014, an incident occurred in Korea that was tragic enough to alter

the very structure of people’s minds. It was

only after undergoing a painful change lasting for a few years after the Sewol

ferry sinking that she was able to address a social catastrophe that seemed to

overwhelm her both personally and artistically. In No Planar

Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt(2018), Yoon shows the planar figure

of a human form, together with a sculpture component of silicone skin. Like the

“sphere” referred to in the

title, the human form incorporated into the work is concrete rather than an

abstract shape. The human form used in the work was adapted from physical data

for a man named Matt, which were purchased from a Canadian 3D scanning company.

In A Letter to Matt (2018), the artist explains

that it is “difficult to make a planar figure of a

human body, just as it is impossible to spread a sphere out due to its curves.” Nonetheless, she adds that she has “done my

best to make silicone skin to place on the gallery floor.” The 3D scanning data of the body is not enough to fully grasp the

human shape; realizing it as a physical sculpture is an even more impossible

task. The result presented in the work is a shell without internal structure,

unprepossessingly pressing against the ground.

In many industry areas, 3D graphic images are often used to show

things that are not actually present or to explain things that cannot be shown

in a particular place and time. The same is true with disaster reporting in the

media. Even when the photographs and videos showing the ship upside-down

underwater are vividly realistic, no one viewing them can truly understand the

situation. During the attempts to grasp the tragic particulars of the incident

as they gradually came to light, 3D simulation images began appearing in the

media to analyze the process of the ship capsizing and the passengers losing

their lives. In this case, abstract 3D images become metonyms for the human

body. But as Yoon’s work No

Planar Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt shows, the shapes cloaked in human

bodies do not actually represent anything; they convey very little about the

person behind the shell. Reduced to a shell, understanding crumbles to the

ground, unable to stand on its feet. Very often, the pain evoked by real-world

irrationality and overwhelming violence seems enough to make art into something

very small and private. Sometimes we can only succumb to feelings of

self-deprecation, helplessness, and shame, or seek comfort in fleeting moments

from an insular world. Amid all this, Jiyoung Yoon stifles her screams and

confronts her endless questions as she attempts with difficulty to speak out.

She comments on the concealed aspects of the world, the shock that comes with

their revelation, and occasions for turning subjective perceptions and lives on

their head. She makes us ask why and how we are looking at certain aspects of

what we are viewing.

Sculpture is the body. As seen with the minimalist sculpture of

the past, abstract sculptures with the same dimensions as the body can evoke a

sense of phenomenological presence in the viewer in front of them. Jiyoung Yoon

has drawn both implicit and explicit comparisons between elements of sculpture

and the human body. Instead of using the same cold, anonymous industrial

materials as minimalist sculpture, however, she prefers working with amorphous,

fleshy materials such as latex and silicone. Rather than delving into the

externally visible surfaces, she seems to want to stimulate tactile sensations

by imagining what exists beyond the flesh, as well as the narrative thinking

that arises from that. Like physical symptoms, the sensations of the skin

resemble photographic paper upon which the hidden inner workings are

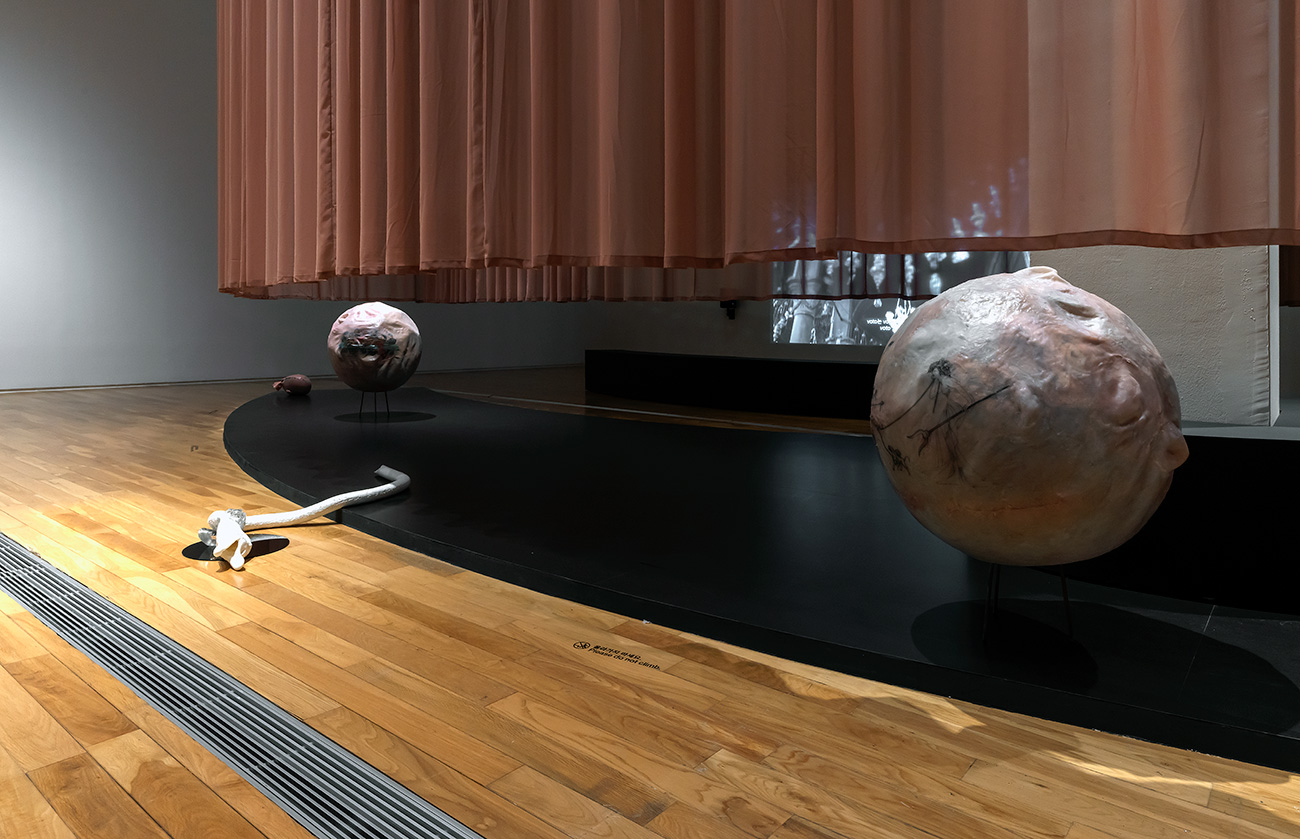

developed. In the Still of the Night (2019) is a

spherical sculpture with a similar volume to the human body, which is designed

to reveal stories inscribed on its surface as it reacts to the surrounding

temperature. To see the obscured content, the viewer has to hold the sculpture

close and convey the warmth of their body. As the artist explains, the viewer

also has to continue withstanding the heat of their own skin. Where No

Planar Figure of Sphere_Allegedly Matt used the human form as a

metonym, the sculpture in works such as In the Still of the Night—which offer a more in-depth presentation of the artist’s ideas about the body—becomes a metaphor

for the physical person. When sculpture metaphorically presents the body, it

demands an expanded kind of reflection on that body. At the same time, the body

is also a metaphor for sculpture, demanding an expanded interpretation of the

sculpture medium’s visual aspects.

One of Jiyoung Yoon’s primary focuses is on the female body. In Korean society, women’s bodies are a battlefield on which the symbols associated with

discrimination operate in the most extreme ways. The reemergence of feminist

attitudes over the past decade or so represents a larger global phenomenon. In

Korea, the #MeToo movement and other hashtag campaigns began surfacing around

the culture and arts worlds in 2016. As women’s

movements proliferated online, they began powering a social debate by

intensively visualizing previously concealed realities of sexism.

Misogynistically motivated crimes began receiving major media coverage, with

repeated displays of commemoration and condolences toward the victims. Amid all

this came news reports about the so-called “Nth Room” on Telegram—a case involving the production

and circulation of videos showing women coerced into situations of sexual

exploitation. The shockingly systematic nature of the crime and the enormity of

its scale forced people to confront a structural collapse within society. More

than just an issue of pornographic perspectives in which women’s bodies were sexually objectified, this was a frightening episode

that alluded to the future destruction and alteration of humanity. Sensing the

urgency of the situation, Jiyoung Yoon adopted an unusually straightforward

figurative approach to create her work Leda and the Swan (2019).

This work, a collaboration with female tattoo artists, explores the iconography

from a Greek myth concerning rape by the god Zeus, while redirecting the

voyeuristic perspective toward the male rather than the female. This appears to

mark the time when the artist began focusing her explorations more on attitudes

relating to women’s shared existential horizons.

It is not only personal misfortunes and social catastrophes that

threaten to erase individuals and art. More than a given incident, it is the

incident’s structural core that operates in more

destructive ways. Jiyoung Yoon engages in a deeper exploration of sculpture’s inner and outer aspects as she reflects fundamentally on women’s corporeality and stands up against different forms of crisis. When

individuals around the world were isolated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the artist

began working to visualize a painful self-consciousness and discordance that

seemed to grow in proportion to the impoverishment of physical perception and

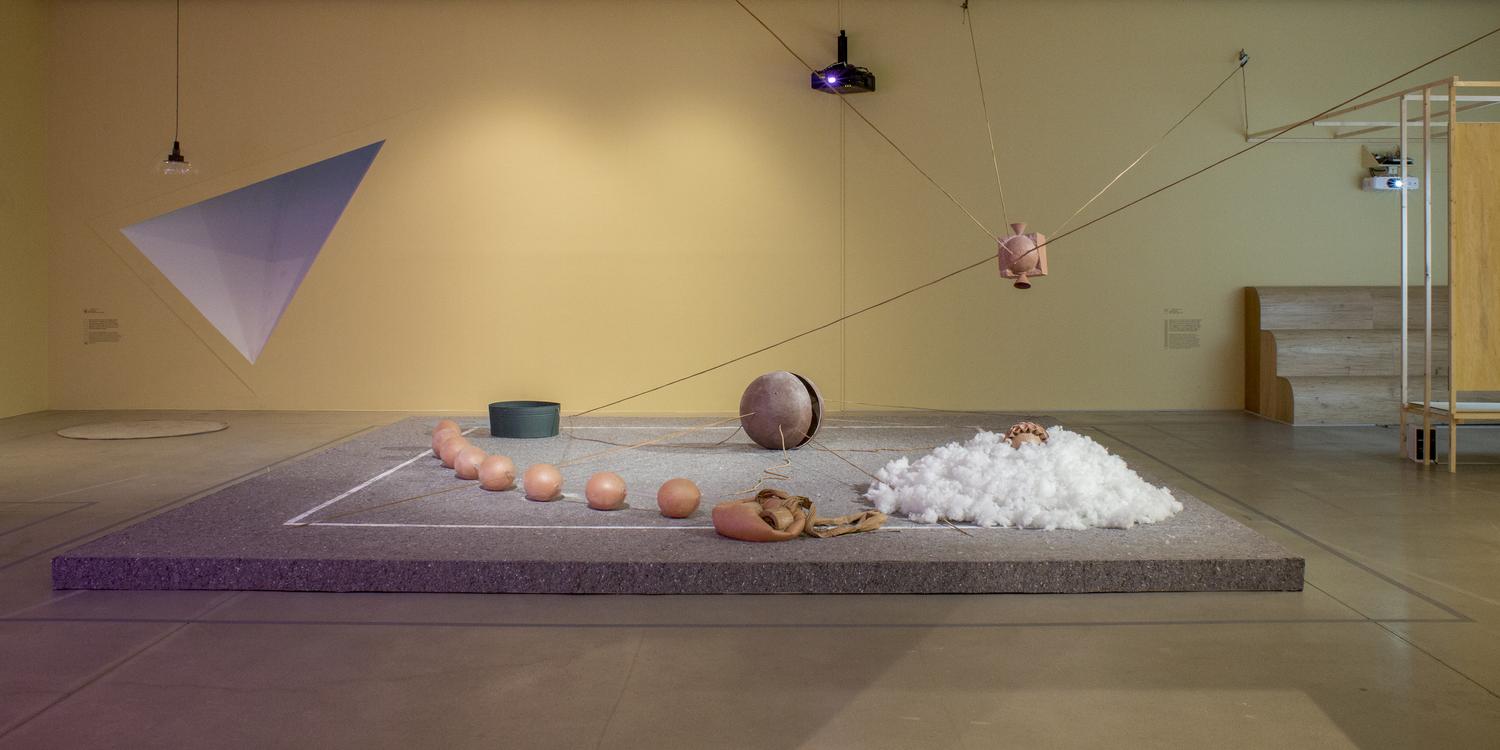

experience. Me, No (2021) is a human-sized work in

which six figures with identical volumes but different shapes trade “clothes” with each other. One sculpture in

the shape of a pillar with a star wears the skin of a spherical sculpture,

which seems ready to split apart; the star sculpture’s

skin hangs baggily over another sculpture in the shape of a pillar with a heart

cross-section. The sculpture’s frameworks—their outwardly visible interiors—are

presented in Vantablack, which reflects almost no light. Silicone has been used

to make the exteriors: the clothing/skin is precariously draped over rigid

structures that tear through them in places. The mournful beauty conveyed by

the work leads the viewer to consider the misalignments between

interior and exterior, the scars of separation, and the story of how these

six sculptures quietly came together.

To Deliver

The visual language of art can often be subtle and poetic enough

to give the sense that it refuses to present itself clearly to all. Yet this

subtleness is not meant to exclude others; it is intended to implicate them

more deeply and elicit emergency thinking. In a Seoul art world that has been

generally urgent and exhausting over the past decade, Jiyoung Yoon has

tenaciously and uncompromisingly sought her own language. At the same time,

exhaustion and extinction appear to have been constant concerns. The physical

properties of sculpture are such that it is fated to wear down and age, and

time takes its toll on the physical capabilities a person needs to work with

such heavy and demanding materials. At the everyday level, the human body’s perceptions and senses have been transforming with the spread of

digital media. In the face of global ecological crisis, artists whose creation

involves physical intervention must consider the ethics of ecological

(non-)intervention. In a world like this, can sculpture and the contemplation

of its medium survive—and if so, how? One thing is

clear: The fate of sculpture as an artistic medium is not separate from the

fate of existential subjects and individuals as members of social structures.

Rather than seeking a lone path of autonomy as an artist, Jiyoung

Yoon has been willing to embrace the chaos of dialogue and collaboration. In

one interview, she said that it is “important to me to surround myself with people whose ideas I believe

in” and that “only then can I

ask questions, listen, and accept.”3 During the pandemic, she co-created the 2020 work To

Deliver with Stephen Kwok, a fellow artist living on the other side

of the world. Amid the constraints on physical meetings, this creation captured

a desperate attempt to share physical characteristics (if only) through digital

space. Faced with the uneasy premonition that everything she had known and

believed might disappear, she relied on the powers of friendship and solidarity

to make creation and life once again possible. She had no choice but to give

everything and “deliver.” The

pain that we endure without escape—without even

thoughts of escape—has the merciless power to turn

everything into nothing. Here, Jiyoung Yoon has always sought out all things as

though starting over from square one. This inevitably demands all one’s strength. It may not be clear what each of us is looking at, but

vision is ubiquitous and fairly granted. What is not visible here does exist—through the choices of the sculptor.

1. Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain, Korean trans. Mei

(Paju: May Books, 2018), 10.

2. Jiyoung Yoon, The Back Stories (2023), video

presentation given at Common Ground as part of the DAAD (German Academic

Exchange Service) Artists-in-Berlin program. https://vimeo.com/858739023

3. Jiyoung Yoon (interviewee), Wonjae Park (interviewer), “Artist Talk | Jiyoung Yoon,” ONE AND J.

Gallery YouTube, February 25, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7m2qTO5lQM