3. The Faceless Portraits Drawn

by Storytelling Machines

The stories conveyed by Yang

Jung-uk’s machines are about the reality of a subject.

Earlier, we noted that Yang’s works are a form of

storytelling that begin with people, rendering them a kind of portrait-making.

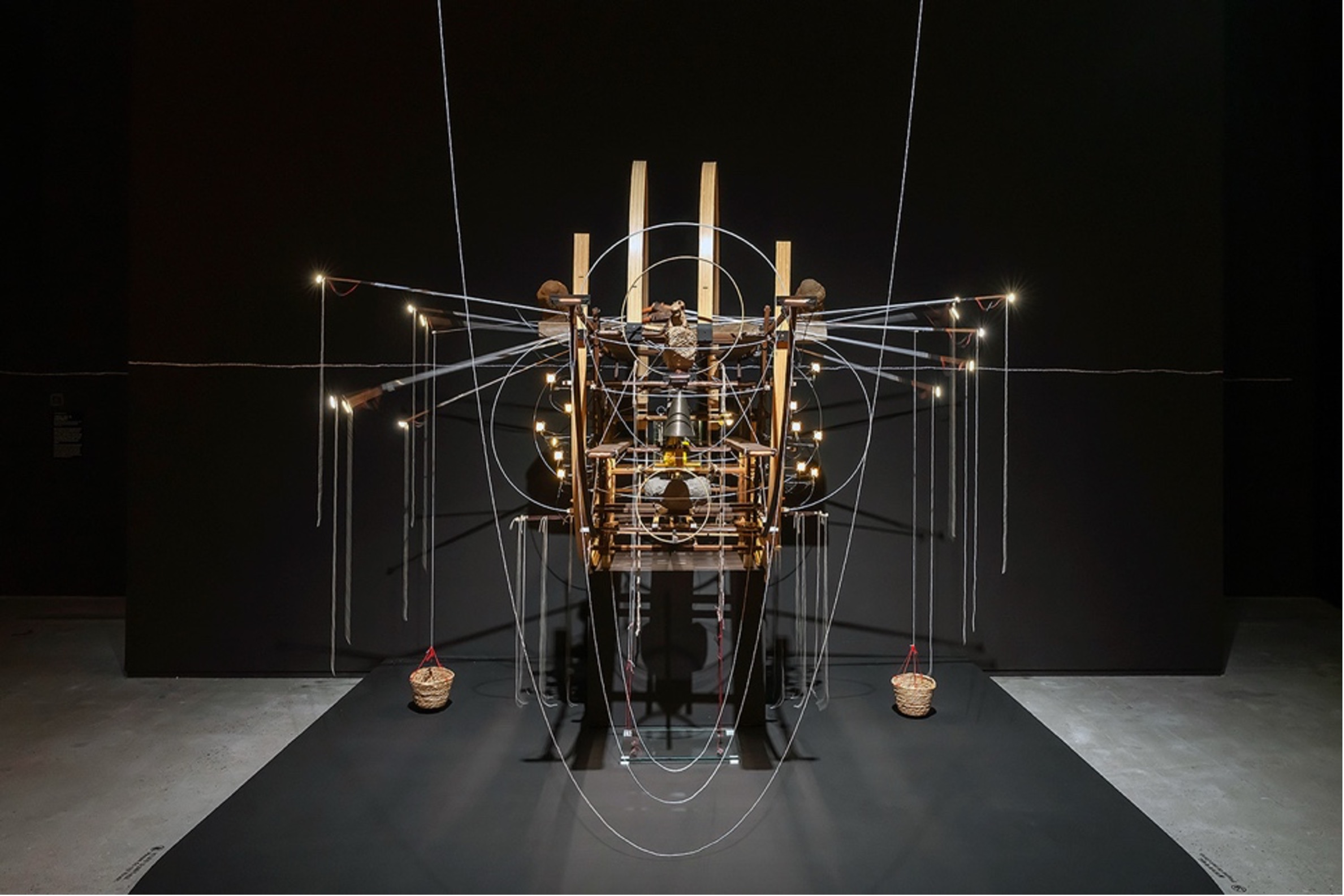

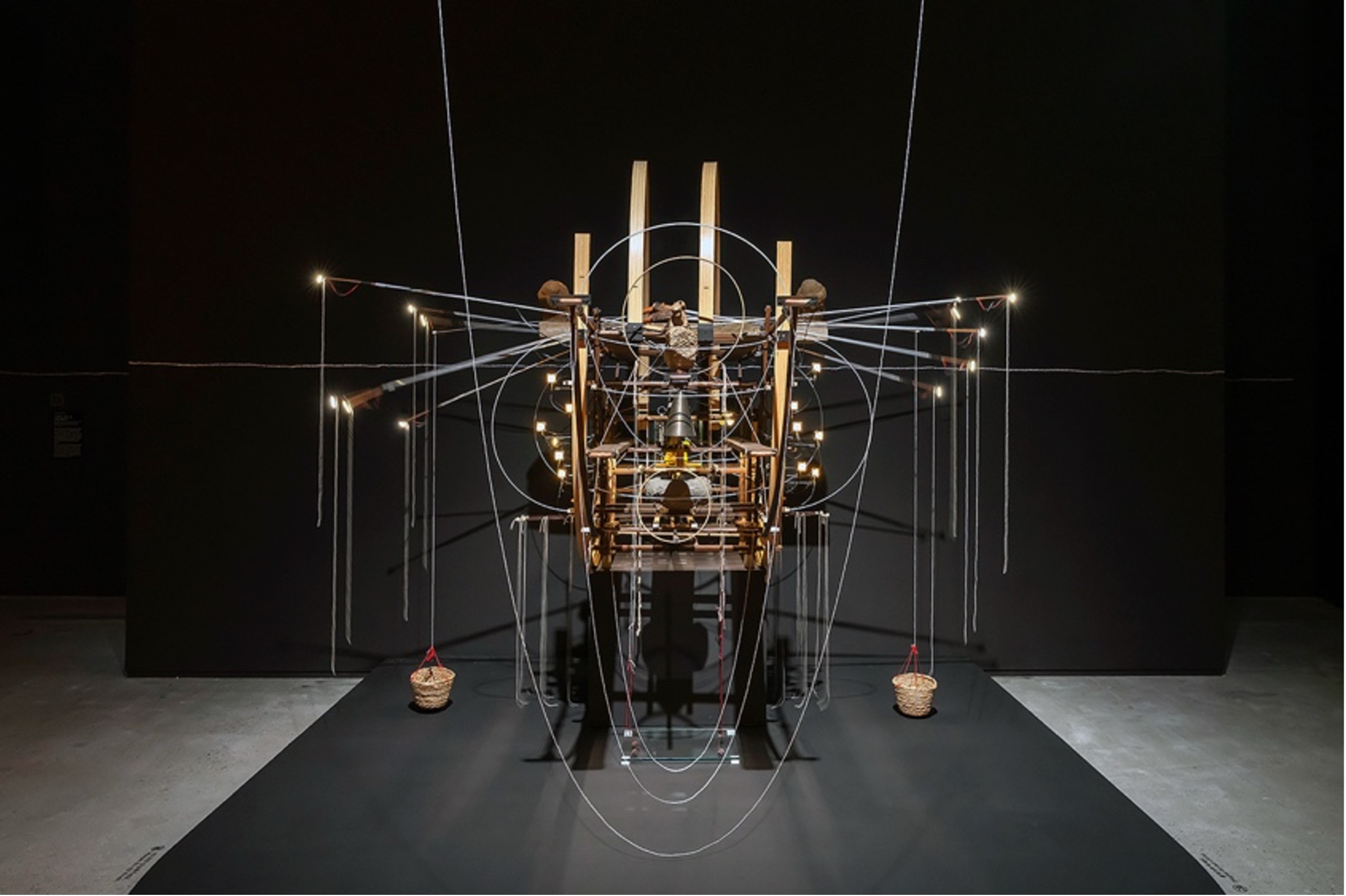

The artist imagines the material structure and movement of his works based on

his observations of the people he encounters in everyday life and the emotions

they evoke. Put another way, this portrait-making does not start from the face

but rather from the body—its posture, movement,

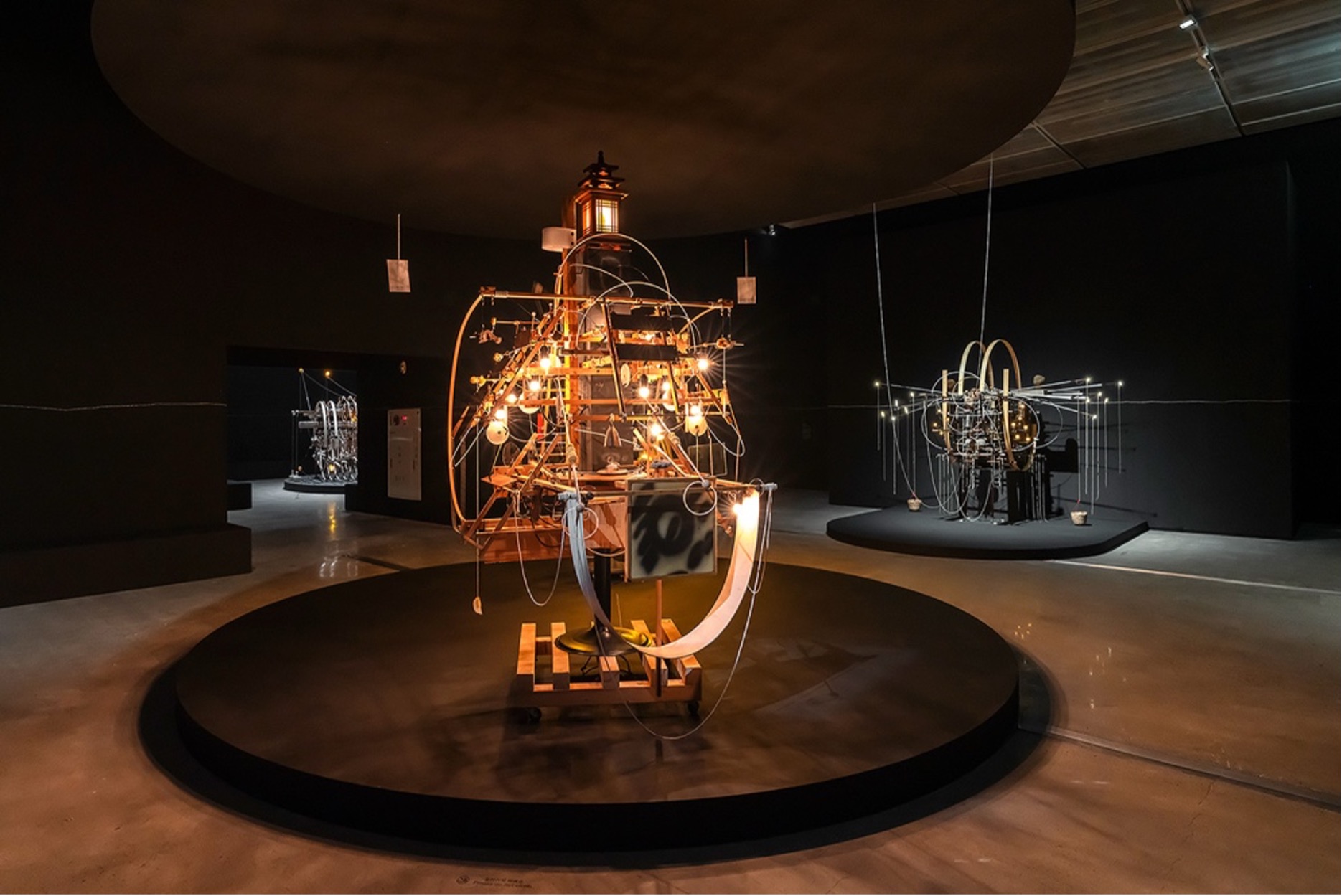

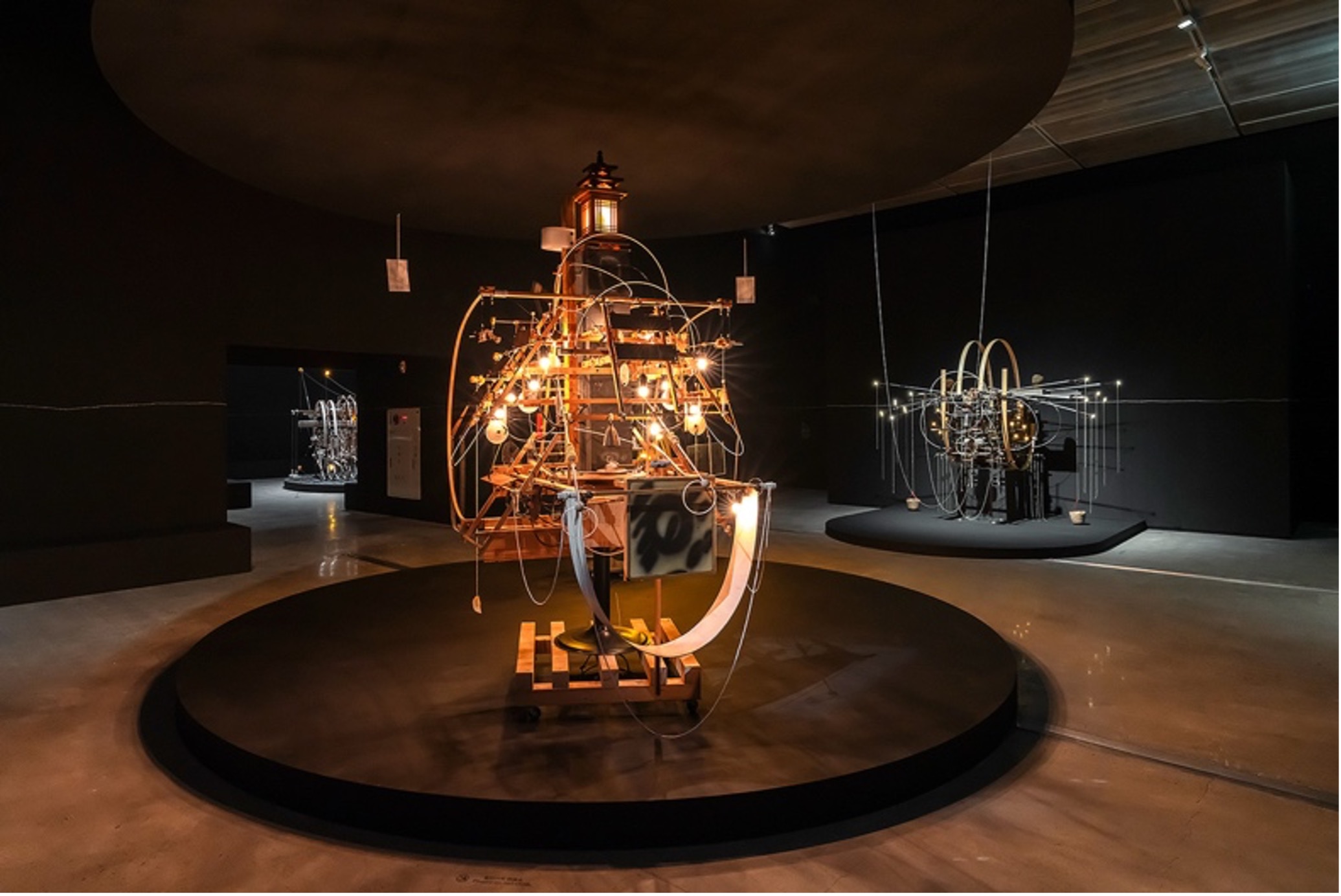

tension, and relaxation. Yang’s storytelling machines

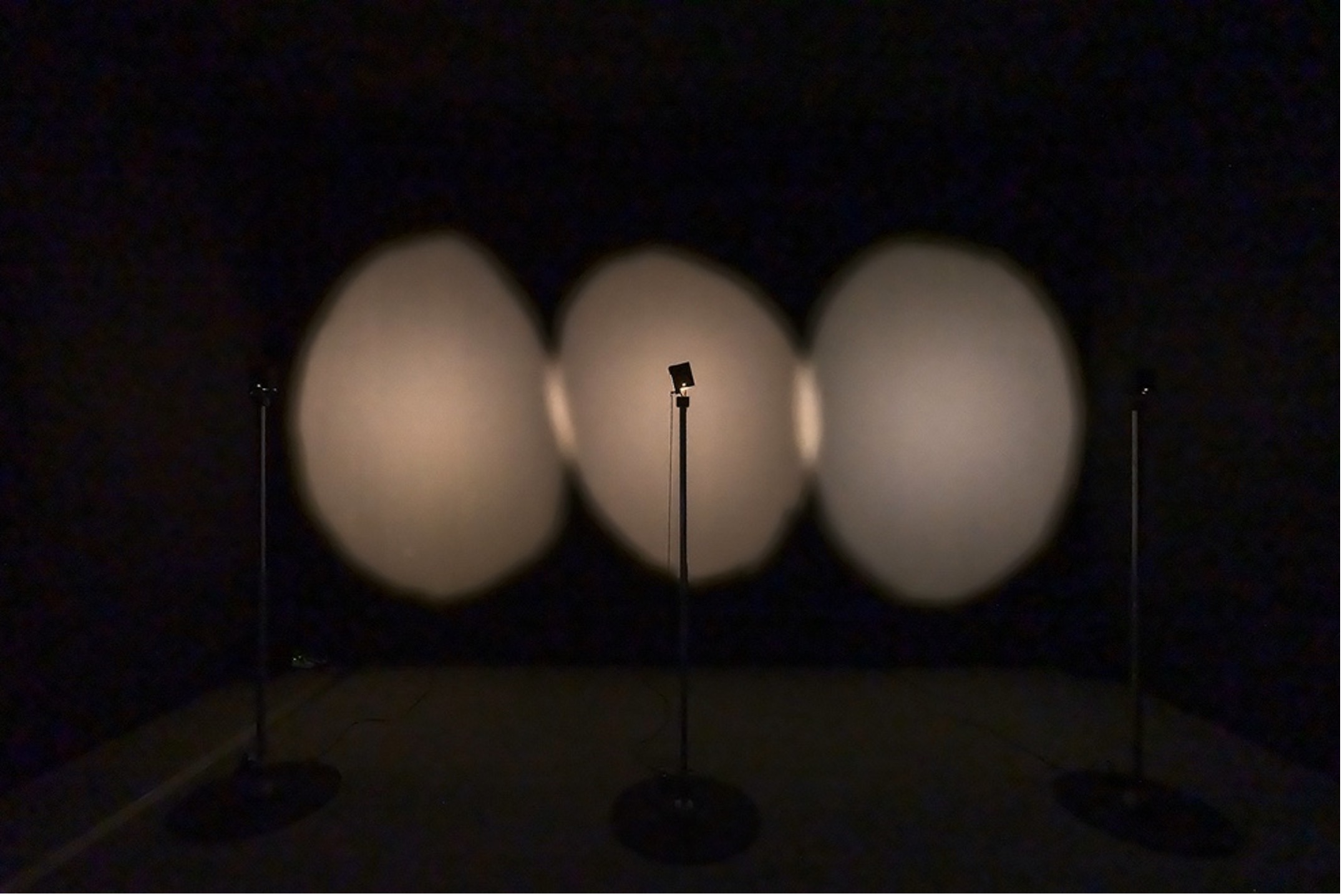

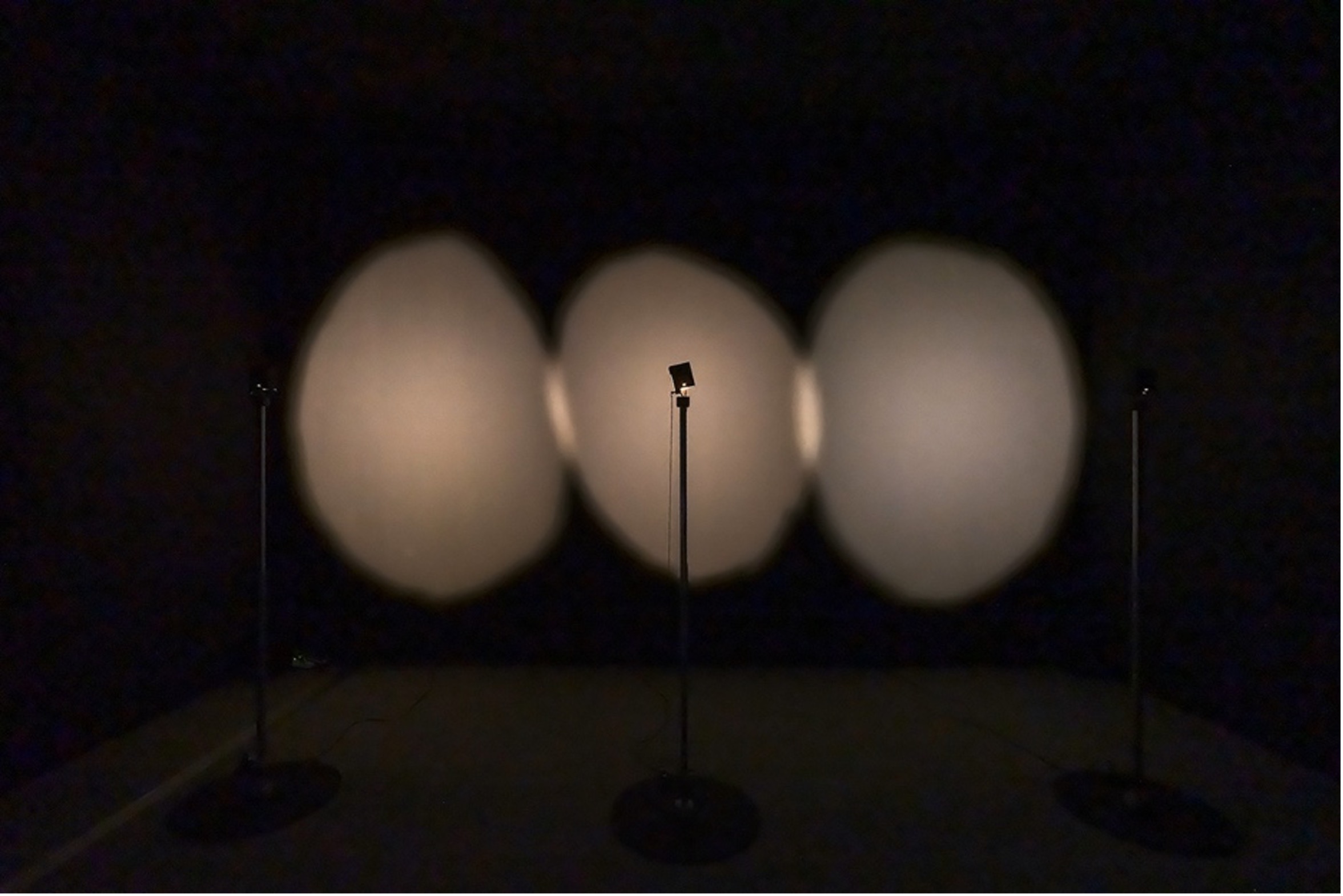

convey their stories not through symbols in language or images but through a

pre-signifying regime of signs, such as gestures, rhythms, noises, and light.

As a result, the story transmitted by these machines are something to be experienced.

And because the stories of the observed figures, the presence of the moving

body, and the dimensions of imaginative expression are intertwined, Yang’s machines become something strange—neither

fantastical bodies of illusion nor rational mechanical devices.

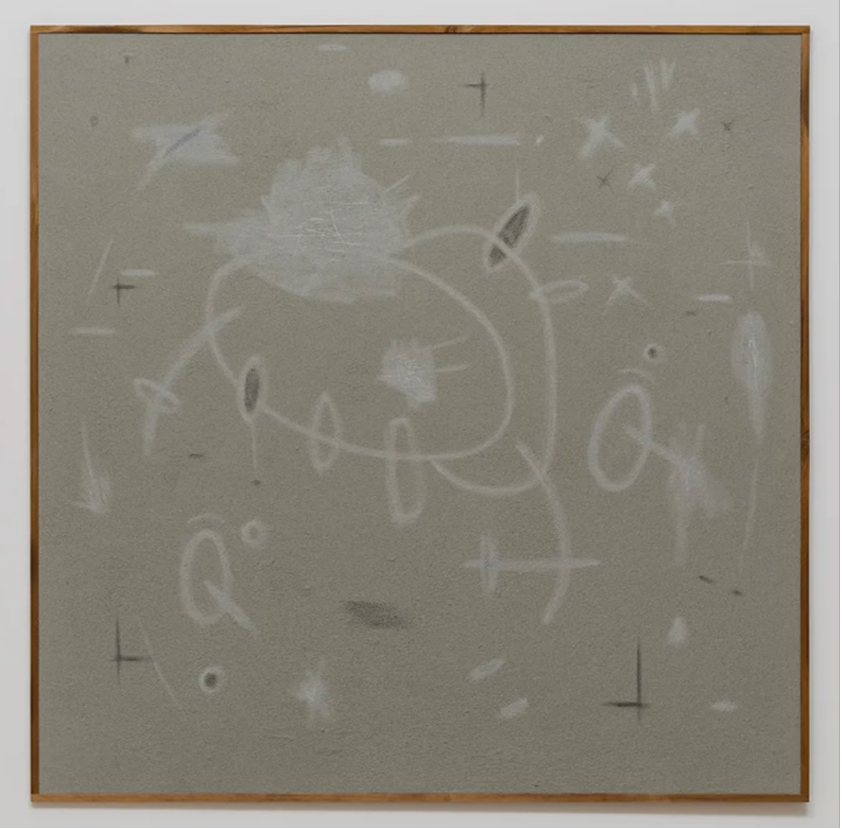

Yang’s machines form signifiance and the strata of subjectification,

which Gilles Deleuze, another French philosopher, and Guattari emphasize as two

distinct axes in the regime of signs. For the signifiers inscribed to construct

a story, as well as for the subjectification derived from the consciousness and

affects formed by the arrangement and movement of the machine’s pre-signifying elements, the artwork needs a “white wall” for inscribing signifiers and a “black hole” of subjectification for

positioning consciousness, affects, and excesses. Deleuze and Guattari both

mention a face that these two layers of signifiance and subjectification

produce, and this is born from an abstract machine that they call the “faciality.” This abstract machine of

faciality operates according to the needs of economics, collectives, and power,

producing an unindividualized face. In fact, this machine creates a system of a

black hole and a white wall, thereby enabling the social production of faces.

However, a machine that escapes from this social production of faces produces a

deterritorialized face. The deterritorialized face includes not only the eyes,

nose, and mouth but also the face-like chest, hands, entire body, and even the

tools themselves. By distancing itself from the signifiers that engage with the

facialized body, the body can be decoded.5 With respect to Yang

Jung-uk’s machines, they go beyond the

deterritorialized face that Deleuze and Guattari discuss, performing a type of

portrait-making through the decoding of a faceless body. Instead of creating a

face by imprinting two eyes or erecting a white wall to imprint the eyes on,

Yang assembles workable limbs.

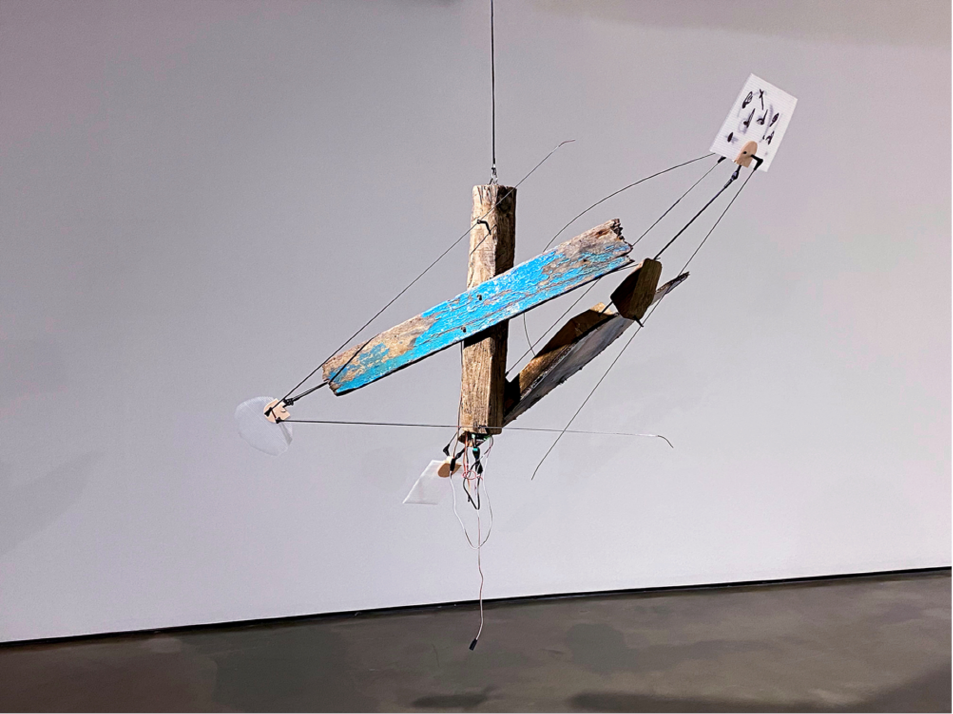

The strange portraits drawn by

these machines are constructed along two axes: one is the axis of signifiance

through storytelling, while the other is the axis of subjectification through

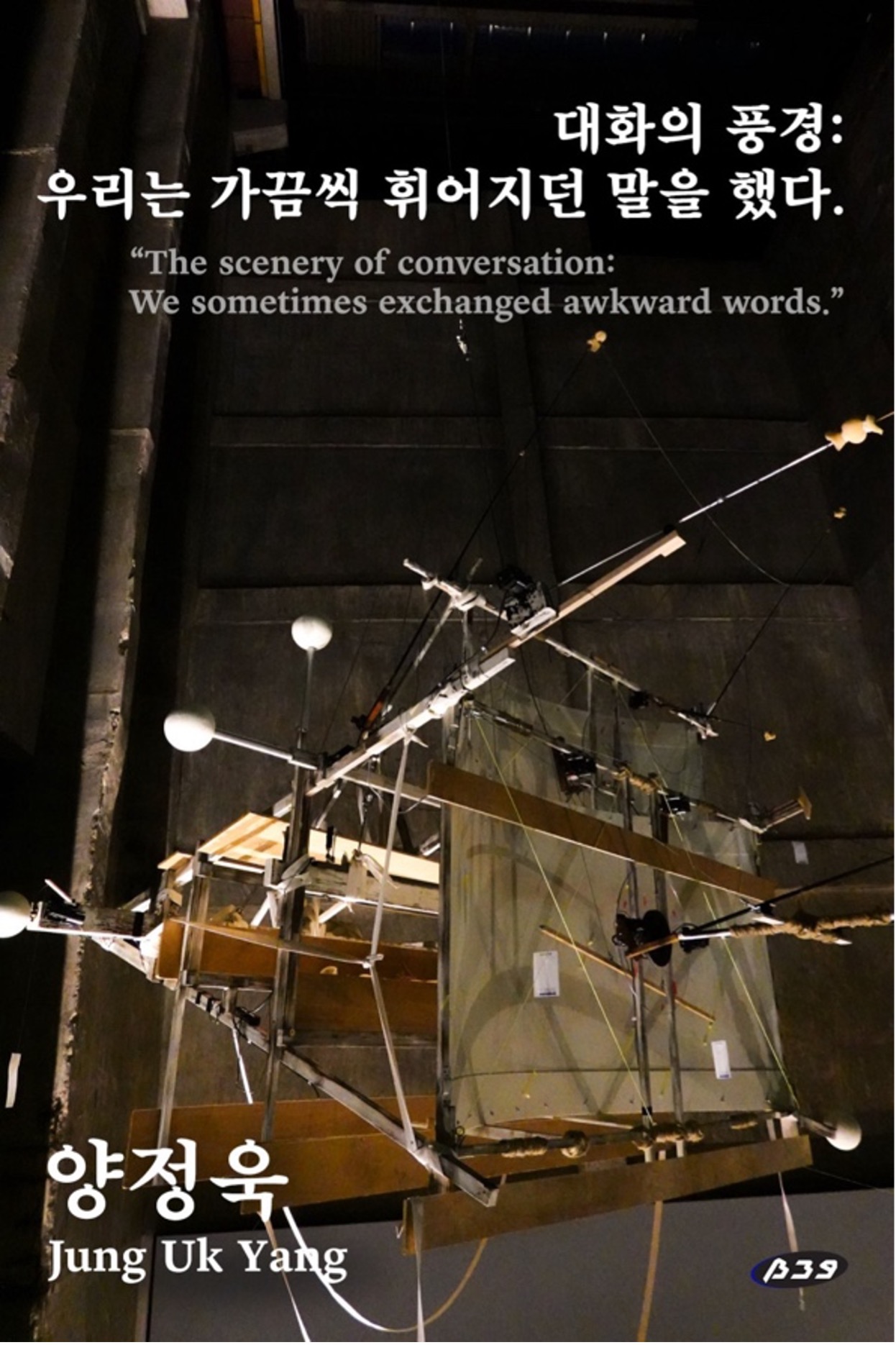

mechanical movement. The story transmitted by such a machine begins with a

sentence presented in the title of the artwork. Each title encapsulates a scene

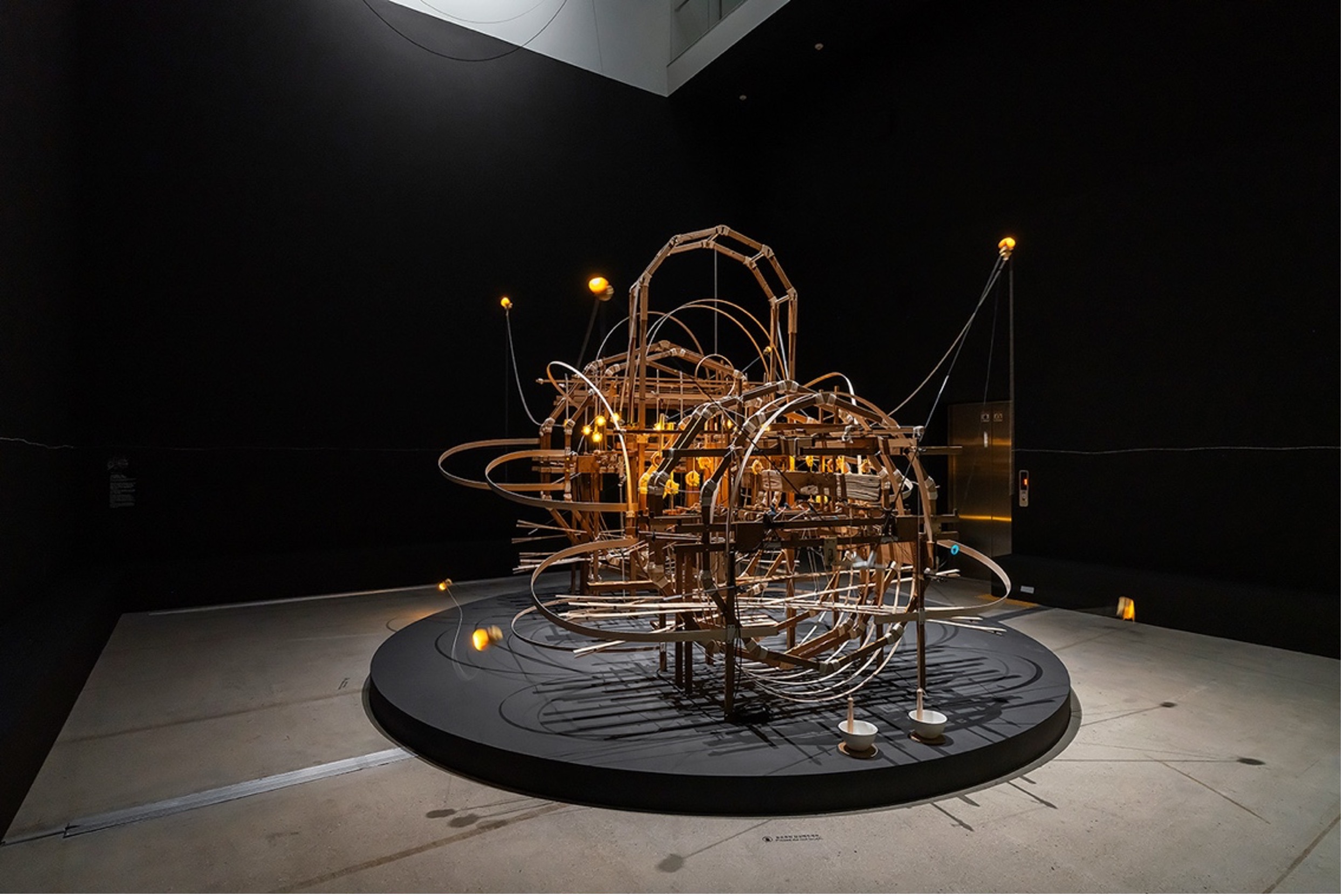

or a moment of intuition, with the story starting in the title, such as Where

Do People Go after Lunch? (2012), The Three

Siblings Are on Their Way Home, But It Feels Like They Are Going to the

Store (2013), Only the Turtle Does Not Know Our

Weekends (2014), or Did Your Father Sleep Well All

Week? (2016). From these storytelling machines, a balance is

struck between reality and imagination, and from this balance emerges pathos.

Yet this intensity does not stem from facial expressions but actually from the

complex ritornello created by the fragmented body. Guattari’s ritornello is a repetitive continuum that crystallizes existential

affects, encompassing dimensions of sound, emotion, and the face that

continuously permeate one another.6 Essentially, the movement

created by Yang Jung-uk’s machines is this very

ritornello.

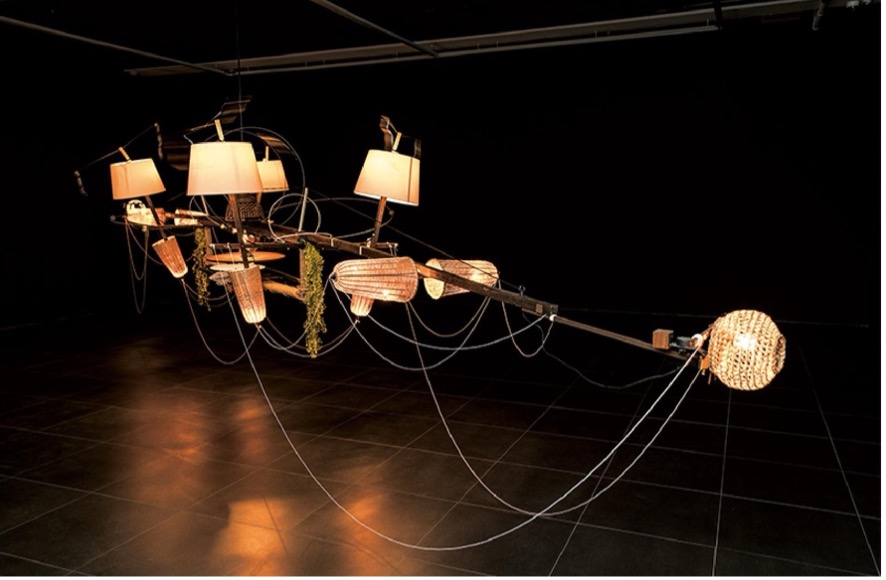

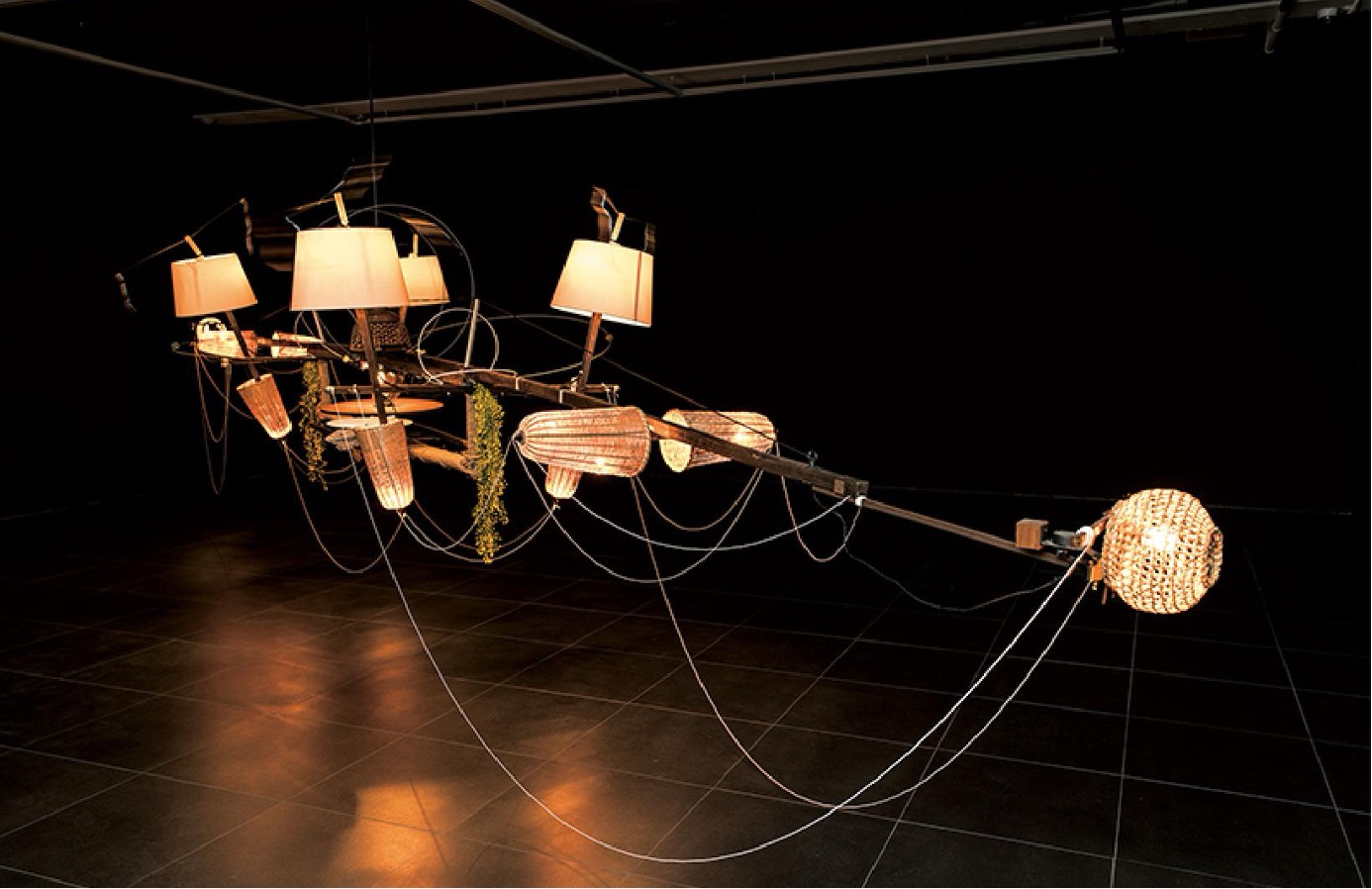

Yang Jung-uk seeks to find the

tension and balance between intuition, stories, and effects as he constructs

his machines from fragments of divided bodies. These machines are devices of

deterritorialized faciality on a deeply personal level. They are not only

arrangements of physical elements but also aesthetic machines that carry out a

literary mission while offering sensory experiences at the same time. Through

these machines, the artist envisions the expansion of tense relationships,

along with the diversification of senses and meaning. The portrait drawn by a

storytelling machine is depicted through a ritornello of decoded bodies within

a single story. As such, the story, which resides in the realm of language, is

brought into reality through movement within physical space. Unlike fleeting

stories generated by digital devices and networks, the storytelling machine

employs a story that repeats endlessly. At its core, it tells a story that

begins with a single observation in motion—through an embodied repetitive structure, just like the stories that

have been repeatedly told since the earliest times when human experience and

memory were transmitted in words.

In this sense, Yang Jung-uk’s works can be described as faceless portraits drawn by storytelling

machines. These portraits, experienced alongside the viewer, offer insights

into life and humanity through intersubjectivity. They resemble the strange

tremor and shock one feels when gazing at their own face in the mirror, when

interacting with family members, when encountering others throughout life, or

when casually reflecting on the surrounding landscape. However, instead of a

chilling black hole and a white wall, Yang’s machines

reveal gestures and sounds that are released upon their deconstruction. What,

then, does this repetition ultimately reveal? Could it be a portrait of the

human being observed through the black hole’s gaze—a glimpse of life’s truth?