Even from a contemporary

standpoint, we can easily think of objects offered with hope, or rituals that

require such votive objects. For example, the candle offerings in Catholic

churches, the rice dedicated to Buddhists temples—the origin of these objects

would be ex-votos. Even today, the entrances of Catholic chapels in Italy,

named after saints believed to protect the living from sickness and misfortune,

are festooned with metal plates and simple objects engraved with personal or

prototypical prayers, consecrated by visitors from all over the globe. If in

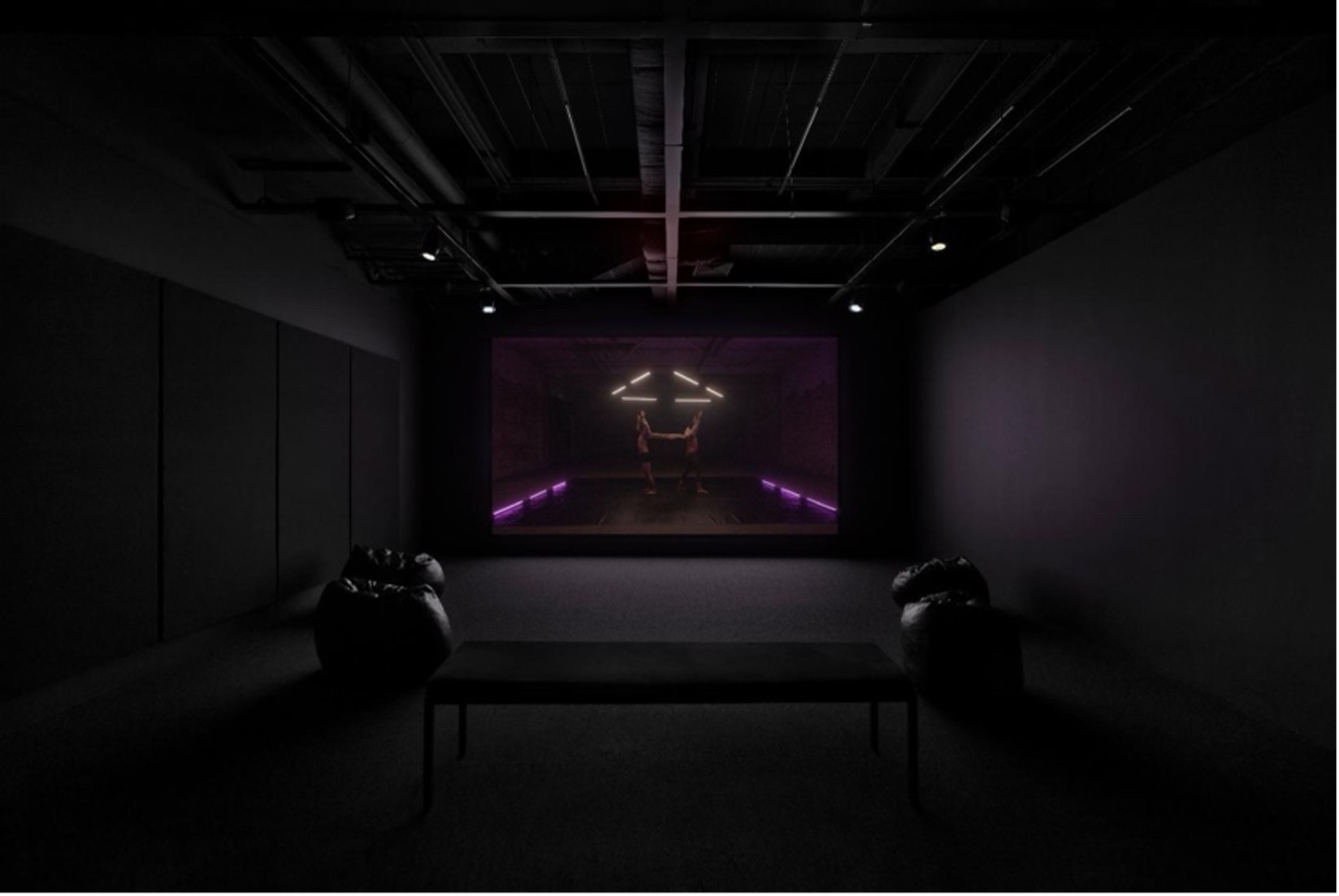

the past, people sought after the experience of “an aura” within churches or

other sanctums, people of today look for “auras” inside the screens or on

stages (museums exhibiting the works of great artists may also be one such

place). The celebrities standing in the center of these places are indeed

bearers of aura, strictly retained through distance—or manifestation of an

unreachable distance (though some may seem to approach their fans if only on

stages or in cyber environments). These stars are showered with gifts, a custom

only continued in a slightly altered manner after their deaths. Around the

gravestone under which a celebrity is buried, pile up letters, flowers, and

small pendants the fans used to keep close. These objects are modern-day

ex-votos, offered with hopes and desires by fans who believe in the sanctity

and the mystical powers of their artists.

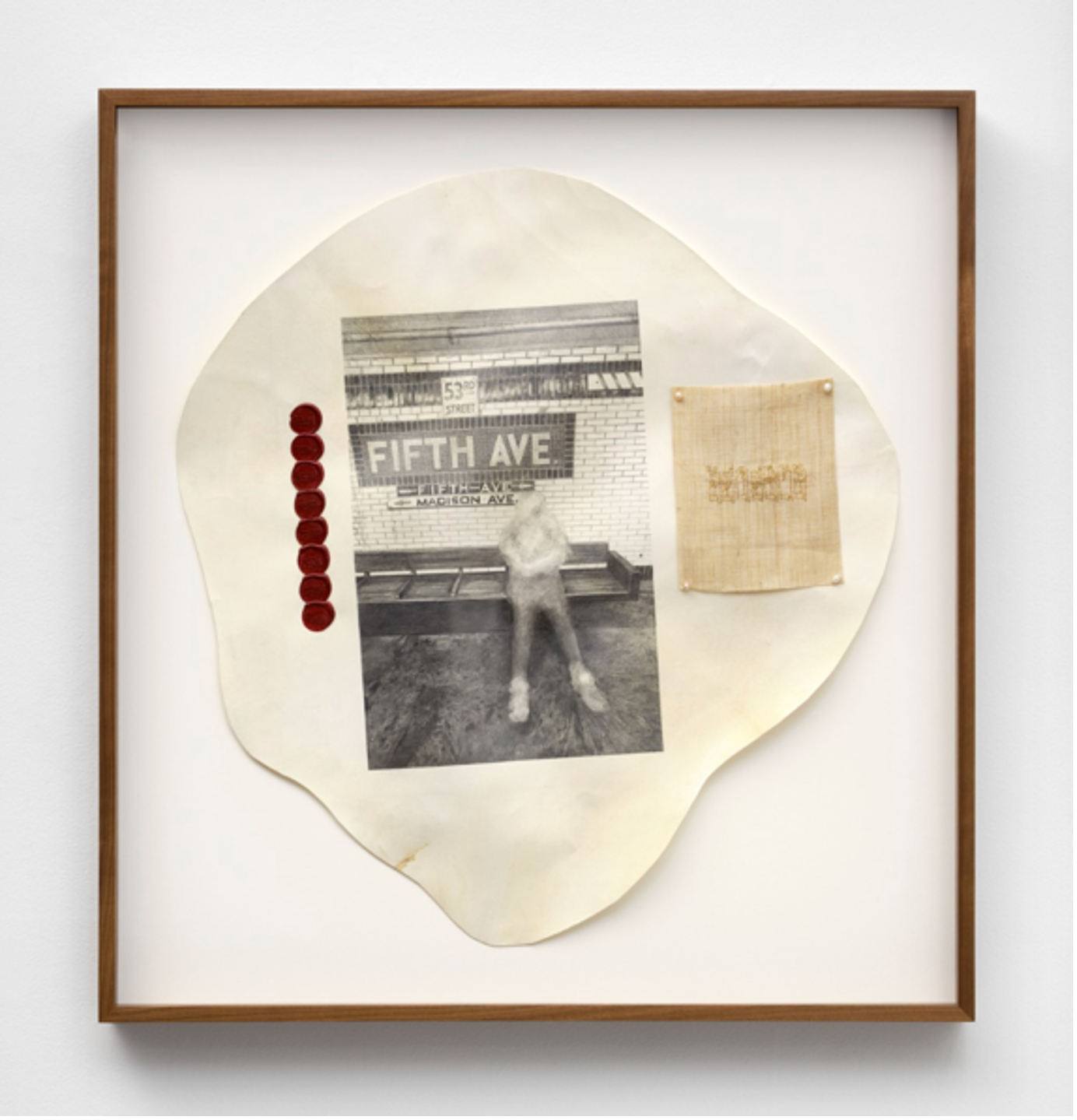

Going back to older forms of

ex-voto: most of the ex-votos found in the various sanctuaries are known to

have been primitive and common objects, far from precious, and often resemblant

of human anatomy. Oblation of commonplace or anatomical ex-votos began among

groups of pagans, even before Christian domination of the European spiritual

culture. What’s interesting is that the ex-votos from Greek, Roman, and

Etruscan Antiquity share the same qualities as the ex-votos seen in the

Christian sanctuaries of Cyprus, Bavaria, Italy, or the Iberian Peninsula: from

size and choice of material to fabrication technique and styles of figuration,

ex-votos have not evolved much. Georges Didi-Huberman, who studied

characteristics of votive objects neglected by most art historians, noted that

these objects have been assigned a position far removed from “the grand history

of style” because of their “aesthetic mediocrity, their formulaic and

stereotypical character,” explaining that the anatomical vulgarity in the objects

threaten the aesthetic model of art established by the academies and normative

criticism. But these ex-votos weren’t randomly chosen common objects; they were

mostly objects that had been touched by sovereign events or symptoms, select

objects related to experiences of calamity or miracle. If a man were healed

from a leg wound, for example, he would offer the crutch or cane used during

his recovery. In addition to crutches, all forms of primitive prosthetics used

on injured bodies immediately became objects of oblation: stretchers that

lifted the injured; planks where a cripple sat; clothes worn by the deceased;

even weapons responsible for bodily wounds. Objects that serve as the aftermath

or evidence of a bodily struggle could be formalized as ex-votos. In other

cases, people consecrated objects dear to them, just as a fan would dedicate to

a celebrity an object that holds a special memory of them. According to this

spiritual logic, medieval worshippers offered bread, live animals, valuables,

and even their own children to the church. Expressing his keen interest in

ex-votos, Didi-Huberman stresses the importance of Warburg’s claims as well as 『History of Portraiture in Wax』(1911) written

by Julius von Schlosser (1866–1938), a late-19th century Austrian art

historian. (Didi-Huberman also showed great interest in the works

of Medardo Rosso (1858–1928) who used wax as his formative medium.)

In terms of art history, Schlosser was a significant figure who helped give

name to the concept of the unconscious mind in Freudianism and also helped the

institution of photography reconsider the value of reproduction and imitation

enabled through technical developments and achievements. Schlosser was

intrigued by the history of the wax portraitures neglected by the museums on

one hand, and the history of wax ex-votos on the other. Historians confirm that

the overwhelming majority of the medieval ex-votos were in fact, wax

portraitures. Schlosser, in this sense, studied the history of wax portraitures

as the only type of sculpture dealt neither by museums nor art history, despite

their coverage of all other sculptural bases—marble, stone, wood, and

ivory—which is to say that he studied the history of wax portraitures excluded

from the category of art. His subjects were anatomical models, ex-votos, and

relics made of wax. What was it about wax as a medium that mesmerized him so?

Wax portraitures are often modeled after someone living or dead, hence there is

the element of direct contact or physical relation between the model and the

portraiture. Given such a relationship, wax portraitures, just like analog

films that embody direct evidence of the actual model, have characteristics

that serve to reinforce the purpose of an ex-voto as evidence or a relic.

Furthermore, wax is a medium endowed with plasticity, therefore a material

suited for image fabrication and reproduction. Let’s picture a scenario: a

patient, who’d been lame in one leg, is now healed and wants to offer an

ex-voto of gratitude to his god. He could offer the crutch that had supported

him through his battle with the illness, or, instead, he could have mocked up

and offered a wax leg. Whereas he can only offer his crutch as an ex-voto of

gratitude once he has healed, which is to say in the time of the satisfaction

of his vow to get well, a wax leg could serve as both an ex-voto of expectation

and gratitude, incarnating the changing conditions as the lame uses his crutch

throughout the healing process.

“Wax . . . adapts itself

plastically to misfortunes and to prayers, it can change when symptoms and

desires change. If the lame find themselves healed in the leg but succumb to a

bad dose of pneumonia, they can always melt down their wax leg and use the recovered

material to make a beautiful pair of votive lungs. . . . Wax, as the material

of all manner of plasticities, lends itself perfectly to all the labilities of

the symptom that the votive object tires magically to involute, to heal, to

transfigure. Wax . . . is polyvalent, reproducible, and metamorphic, exactly

like the symptoms it is charged with representing, on one hand, and warding

off, on the other. . . . One might say it permits a gain of flesh.” —Georges

Didi-Huberman, “Ex-Voto: Image, Organ, Time”

On another note, Schlosser

asserted that wax sculptures contributed largely to the advent of realist

portraitures reflective of scientific observation and proportions, and that in

dealing with the emergence of “autonomous portraits,” Giorgio Vasari neglected

the influence of wax portraitures therefore distorting the history. Schlosser

goes on to describe the emergence of realistic wax portraitures, which Vasari

had failed to notice, though there are certain aspects he too overlooks in

eager attempt to rectify the evolutionary schema of portraitures. Didi-Huberman

concludes that, in discussing wax ex-votos, Schlosser may have magnified the

importance of wax portraitures, saying that, in regards to the 1630s for

example, the importance of wax effigies has to be relativized: as opposed to

some 600 wax effigies, there were around 22,000 anatomical ex-votos modeled

after human organs or body parts in Florence. Who is to say that these

anatomical ex-votos unaccounted for in Schlosser’s studies—the isolated ears,

tracheas, limbs, hearts, and even life-size testicles—aren’t as representative

of their consecrators as their portraits? Didi-Huberman goes on to pose

interesting questions and hypotheses about these crude, almost repugnant

imitations of body parts offered to God and their relationships with their

consecrators. Simply put, these anatomical ex-votos do represent their

consecrators. They represent not through realistic description of their

external appearance, but rather, through description of their symptoms, prayers,

the moments of experienced by their flesh. It can be said that what the

consecrators sought to replicate through wax was their state of pain, their

desire for transformation, their hope to reclaim peace and wholeness, their

yearning to change. As can be seen through some of the hypertrophic body parts,

perhaps the characteristics of the consecrators’ misfortune individualizes them

as much as their facial features. But then we encounter yet another skepticism:

how can “loaves” or “raw and vulgar masses” of wax and wax portraitures carved

with finesse hold the same amount of aesthetic value and importance? Wax

sculptures are inherently products of contact (with the model), which makes

them “indicative” according to Charles Sanders Peirce, and owing to the

plasticity of the medium, they embody the potential for resemblance. (Aside

from wax, ex-votos in the form of thin metal plates or paper—also materials

with plasticity—were also common.) Based on the belief that the almost

non-figurative lumps of wax represent the consecrators’ characteristics, we can

infer the definition of “resemblance” prevalent at the time. Didi-Huberman

refers to the medieval ritual that still exists in the Mediterranean basin of

weighing sick children in hopes to save them from their illness: the child is

placed on one side of the scales and wax is piled up on the other side until it

reaches the exact weight of the sick child. In this case, the weight of the wax

becomes the basis of their resemblance. Aside from this ritual, there have been

countless cases in which ex-votos were selected based on their materialistic

resemblance to the consecrator’s “organic weight . . . encumbrance . . . [and]

suffocating presence.” And here lies the paradox that the most organic and

symptomatic qualities are often manifested through the most physical of

properties.