Community, collaboration, and

continual transformation have been central to the works of South Korea–born, Los Angeles–based artist Kang Seung

Lee. For over ten years, he has developed a research-based practice that mines

public and private archives to revitalize the works and legacies of queer

artists, writers, dancers, and gay and trans rights activists who have passed

away. Some of these transnational historical figures have remained well-known

in the present-day, whereas others have fallen into relative obscurity. To

create his works, he has engaged closely with caretakers of these archives and

with those still living who were involved in the histories contained therein.

Lee has employed a range of materials and techniques in his works, including

graphite drawing on paper, embroidery on sambe cloth, collaging found objects,

among others. He has also collaborated with artists and other cultural

producers in his queer community to create ongoing, open-ended art projects,

group exhibitions, and videos.

Community and collaboration have

structured Lee’s practice since his

earliest exhibited works, such as his Untitled (Artspeak?) (2014–ongoing). Billed as a “common-sense guide,” Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and

Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present is a reference book that defines a number

of art movements and terms used in contemporary art; it also features a

timeline that lists, year by year, events categorized as “world history” or “art

history.” To make this work, Lee invited around twenty

people in his social circles in Los Angeles and Cal Arts (where he received his

MFA) to collaborate; each person was asked to “edit” an enlarged, hand-drawn copy of the timeline page in Artspeak that

shows their year of birth. The group of people that Lee invited were diverse in

terms of their age, gender, race, sexual orientation, and cultural backgrounds.1 In

the wide blank margins that Lee used to frame each book page, the participants

added their own annotations, anecdotes, events, and drawings of artworks,

musicians, filmmakers, and others left out by Artspeak. The edits

collectively undermine the implicit masculinist, heterosexual, and colonialist

point of view in Artspeak’s version of history by

introducing multiple historical narratives, ones reflective of the varied

interests and personal backgrounds of Lee’s

international, intergenerational community at the time.2

In recent years, Lee’s communal approach has become more dynamic and open-ended, as

evident in his so-called Harvey project, begun around 2019. This project has

its origins in a work titled Archive in Dirt (2019–ongoing) by fellow artist and friend Julie Tolentino. Archive

in Dirt consists of a potted Christmas cactus plant that Tolentino grew

from a small cutting; this cutting was taken from a “mother” plant that had belonged to San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk

(1930–1978), one of the first openly gay elected

officials in the U.S. who was tragically assassinated less than a year after

taking office. Tolentino received the cactus cutting—which

arrived very limp—in a mailed envelope alongside print

ephemera from a queer activist and archivist friend, who had in turn received

cuttings from one of Milk’s former roommates (who had

been giving cuttings to various friends over the years).3 When

Lee encountered Tolentino’s work, he was touched by how

generations of people had taken care of and propagated Milk’s plant during the four decades since his death.4 Since

2019, Lee has helped Tolentino propagate the “Harvey” cactus and has created his own artworks in response to the growing

number of plants, which have been entrusted to others in their network of queer

friends. The “Harvey” project

generates acts of caring and gifting that have enlivened a sense of community

around a shared desire to keep Milk’s memory alive and

present.

Continual transformation is

integral to the “Harvey” project—which literally changes form as new

generations of cuttings and owners come into being—as

well as Lee’s larger artistic practice. In his works,

Lee doesn’t claim to use original subject matter, but

rather he sees his mode of making in terms of “appropriation.”5 From archives, books, and

particular locations, he collects found images, objects, organic matter, and

other materials with specific histories and symbolic resonances. These source

materials are recontextualized and often translated into other mediums—especially drawing, embroidery, collage, and video, as I discuss in

this essay—in ways that transform their original

meanings. In this way, his works look backward and forward in time, functioning

as spaces for remembrance as well as opening up new possibilities.

Drawing: Presence and Absence

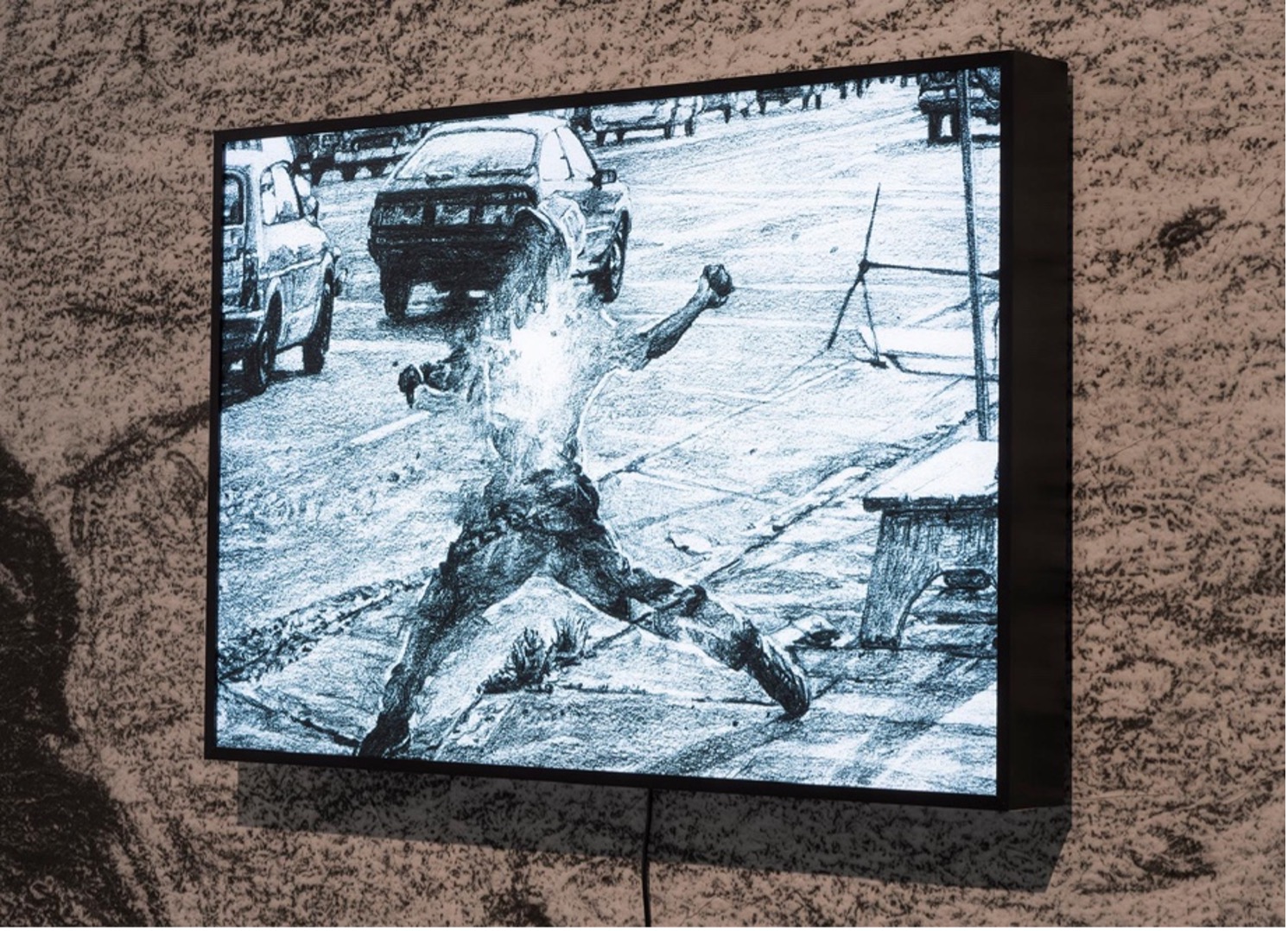

A number of Lee’s graphite drawings memorialize queer lives that have been cut

short, such as those presented in his exhibition Absence without

Leave (2016–2017) at Commonwealth and Council, in

Los Angeles. For this show, he presented meticulous graphite drawings of

photographs that capture the milieu of gay life in the 1970s and 80s,

particularly in New York.6 Source photographs for this series

include a self-portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe, a portrait of David Wojnarowicz

by Peter Hujar, a portrait of Martin Wong by Peter Bellamy, scenes of gay

cruising at the Hudson River piers taken by Alvin Baltrop and Leonard Fink,

among others. Lee’s drawings faithfully reproduce the

photographs save for one part: the human figures are blurred, rendered

unrecognizable, made to appear as if they are disappearing into a cloud of

smoke. On the one hand, the figures’ erasure alludes to

the traumatic devastation wrought by AIDS in queer communities in New York and

other cities around the world, as well as how politicians and governments

initially refused to recognize the epidemic. In the U.S. alone, hundreds of

thousands of people died from AIDS or AIDS-related complications by the end of

the 1990s, including Mapplethorpe, Wojnarowicz, Hujar, Wong, and Fink. Thus,

the drawings can be read as grieving loss, as art historian Jung Joon Lee has

argued.7 On the other hand, the figures’ erasure also indicates Lee’s artistic

intervention into these images, a conceptual prompt that can be read as an

opening dialogue between Lee and these artists of a previous generation. Lee

has stated: “I would like my work to question the

erasure of others who came before and remain unseen, to generate conversations

about the space that holds intergenerational connections and care, and to be an

invitation to reimagine invisibility as potentiality.”8 In this way, the drawings can

also be read as affirmations of presence.

The laborious, time-consuming

nature of Lee’s method of drawing

encourages viewers to linger and slow down their perception of his works. This

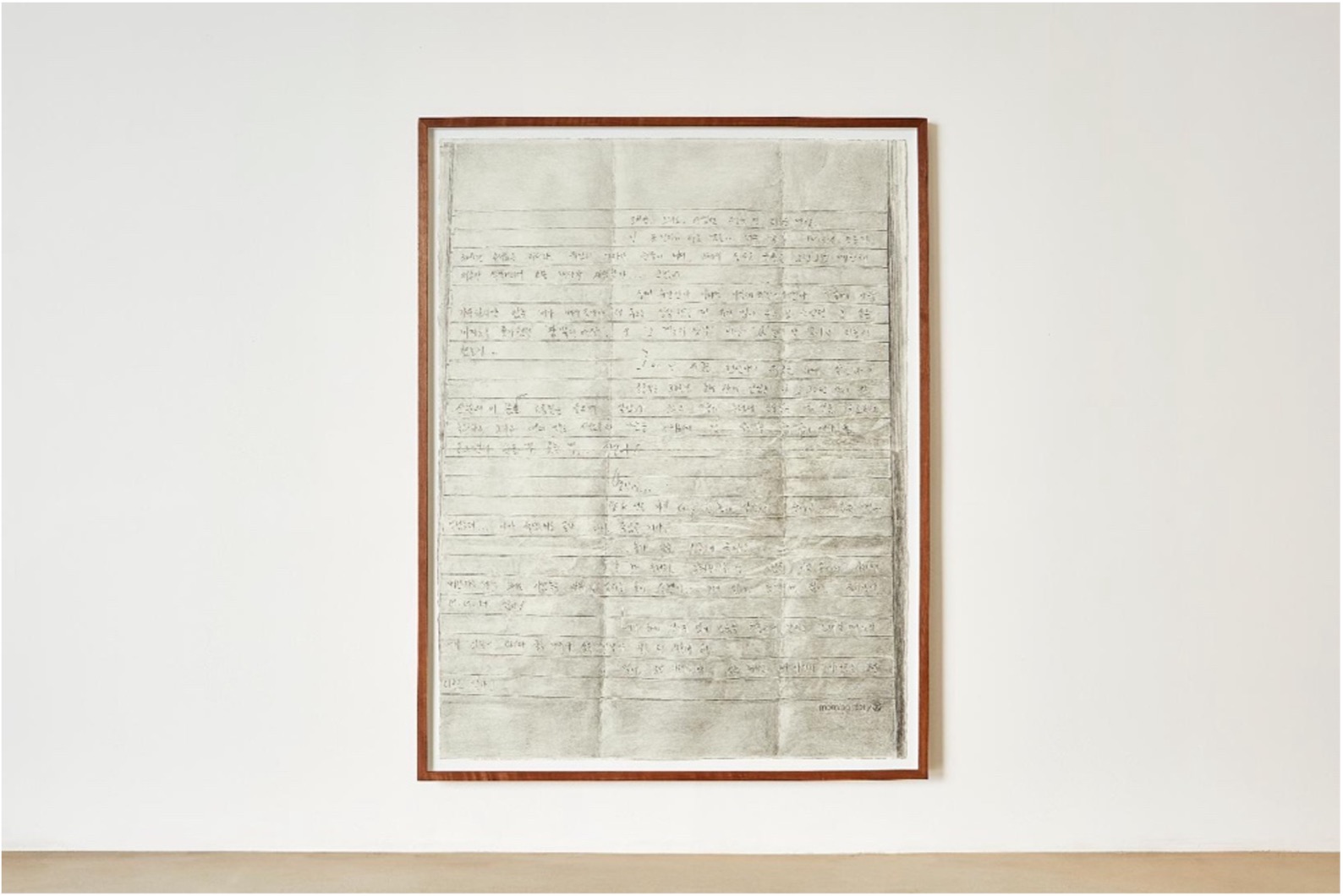

is particularly the case with his larger-scale drawings, such as Untitled

(Joon-soo Oh’s letter) (2018). Whereas many of Lee’s drawings of photographs, such as from his Absence without

Leave series, are intimately sized at around 32 x 28 cm, Untitled

(Joon-soo Oh’s letter) is about five times as

large, measuring 160 x 120 cm. The enlarged scale allows one to read easily the

content of the letter by Korean writer and poet Joon-soo Oh (1964–1998). It is a searing account of his feelings of loneliness as he

listens to music by popular singer Yong Pil Cho and imagines himself

contracting AIDS and dying from it. He expresses his deeply rooted fear of

being forgotten, as if his life had not mattered. Oh was one of the first gay

men in South Korea to publicly disclose that he was HIV positive. He published

a memoir of his experiences as an AIDS patient under a pseudonym9 (he

would die from complications of the disease) and worked with the gay rights

group Chingusai, which he helped to found, for the remainder of his life. In

Lee’s drawing, representations of the letter’s physical qualities stand out, from its uneven tones indicating the

paper’s texture to its carefully rendered creases. The

letter was once folded and sent by Oh to a close friend. The drawing’s large scale monumentalizes the letter’s

intensely personal subject matter as well as the friendship such correspondence

represents. When displayed, its monumental scale allows the work to address

multiple viewers at once—a public—helping to ensure that Oh’s life and work

will in fact not be forgotten.

Gold Embroidery on Sambe: Death

and Eternity

Since 2017, Lee has been making

gold embroidery works on handwoven Korean sambe that evoke notions of mourning

and transience. Sambe, a cloth made from hemp, is associated with funerals and

death in Korean culture. Before the 1950s, sambe was widely used to make summer

clothing for farmers and middle-class families as well as funerary clothing for

mourners and the deceased. Since the 1950s, however, as Western-style clothes

became more popular after the Korean War, sambe has now been used primarily for

burial practices. Sambe is considered appropriate for burial clothing since it

is thought to decay more quickly than other fabrics, such as cotton or silk.10 A

labor-intensive and highly skilled process, handmade sambe in South Korea is

now largely made by a generation of elderly women in rural areas. As more young

women from agricultural regions seek higher education and employment in cities,

and as the ubiquity of imported, mass-produced sambe makes Korean sambe

prohibitively more expensive, the future for Korean-produced sambe seems

increasingly unviable.

Like Korean sambe, the gold

threads in Lee’s embroidery works connote

obsolescence. Lee uses 24 karat gold thread that was produced in the 1910s and

early 1920s in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, long renowned

for its high-quality textiles. To make this material, strips of pure gold leaf

were wrapped around silk thread, a technique that fell into disuse and is now

obsolete. There is a limited quantity left in the world of this specific type

of Nishijin gold thread. Unlike Korean-produced sambe which is still being

produced, though at dwindling rates, at some point the supply of this

historical thread will run out.

While a sense of loss—and the anticipation of loss—underlies Lee’s gold embroidery works on sambe, they are also imbued with a sense

of veneration. Gold has traditionally been used to signify holiness or purity

(among other meanings) in religions such as Christianity and Buddhism.11 In

Lee’s hands, the gold thread makes iconic what is

embroidered, as in his Untitled (Cover) (2018). The source image

for Untitled (Cover) is the cover of a memorial booklet for Oh. In

this image, we see a line drawing of two clean-cut men in suits, looking in the

same direction. One man places his hand familiarly on the shoulder of another

man and seems to move one leg forward to touch the other’s leg. When viewed on the booklet’s cover,

next to the title “In memory of Oh Joon-soo,” the image appears to represent Oh and his close involvement with

Chingusai, which literally translates to “Between

Friends.” In Lee’s embroidery,

though, there is no caption to direct a specific interpretation of the image.

It becomes more free-floating, a charged image of a gesture of affection

between two men, one that oscillates between reading as homosocial and

homosexual. Materially recontextualized in gold thread and sambe, the ambiguous

image of male intimacy traced in shimmering gold becomes timeless, while its

organic hemp support threatens to disintegrate if not cared for under the right

conditions.

Collage: Connecting and Reframing

In many of Lee’s works, collage is used to make unexpected connections between

disparate figures, places, and histories, relating what is recognizable to what

has been obscured to extend visibility to all. A powerful example of his

approach to collage can be seen in his pivotal

exhibition Garden (2018) at One and J. Gallery, in Seoul.12 The

exhibition brought together images and objects associated with two figures who

had never met, Joon-soo Oh and British artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942–1994).13 After coming out as HIV positive, Oh faced

immense social stigma and died relatively unknown; many of his essays and poems

were published posthumously through the efforts of his friends and colleagues.

In contrast, Jarman’s avant-garde cinema, which

combines representations of queer sexuality with a punk sensibility, were

critically well-received during his lifetime and after. Both were committed gay

rights activists and died within a few years of each other from AIDS-related

illnesses. To create his works for Garden, Lee went to Dungeness in Kent,

England, to visit Jarman’s final home and garden, a

place dubbed Prospect Cottage. The filmmaker found and purchased this site

shortly after learning he was HIV positive; he found deep solace in working on

his garden during the last years of his life.14 In Seoul, Lee

conducted research into Oh’s life and work at the Korea

Queer Archive and spoke with Oh’s friends and

colleagues from his time at Chingusai. Throughout Garden, Lee’s arrangements of publications, photographs, personal items,

flowers, stones, and soils, collected in two different parts of the world,

weave together Jarman’s and Oh’s

uneven legacies in a layered remembrance of their parallel struggles and acts

of creation and resistance.

Although Lee’s Garden exhibition as a whole could be viewed through the lens of

collage, his work Untitled (Table) (2018), presented near its start, can be

seen as representative of the show’s premise and his

use of the medium. On opposite sides of a square wooden table top, we see an

array of objects, including stacked photos of Prospect Cottage and places in

Seoul tied to the history of its gay community; a stack of facsimiles of Oh’s daily memos; an issue of Buddy, one of the first gay and

lesbian magazines in South Korea, opened to a spread featuring Oh’s obituary; snapshots of Oh in daily life as well as his funeral

service; a folder of writings by Oh, opened to two pages of a letter; a copy of

Oh’s memoir (under a pen name); and a copy of Oh’s memorial booklet. Down the middle we see a table runner made of

sambe, embroidered in gold thread with the repeating motif of a leaf sprig with

a heart on top. (The motif derives from a curtain Lee saw at Prospect Cottage,

pictured in his print Untitled (Curtain at Prospect Cottage) (2018),

included elsewhere in Garden.) On top of and adjacent to the sambe runner,

we see rusted chain links from Jarman’s garden and

small stones lying in pairs or side-by-side in a group—metaphorical

images of the intimate bond between two entities, or a group of entities. An

unglazed ceramic work made from California clay mixed with soils from Dungeness

and Seoul’s Tapgol and Namsan Parks—storied gay cruising sites that Oh mentions in his writings—sits near the table’s middle, a vessel meant

to be filled with a fresh offering of plants when on view. Above the table,

suspended on a piece of gold thread is Oh’s gold rosary

ring. (Oh, like Jarman, was raised Catholic.)

The emotional gut punch of the

installation derives from Oh’s two-page

letter on display (one page of which Lee drew for his

aforementioned Untitled [Joon-soo Oh’s letter]),

in which he speaks of his aching loneliness in relation to his sadness at not

having experienced profound romantic love and his fear of not having mattered

to anyone. Lee has spoken about using Jarman’s story as

a way to introduce larger audiences to Oh’s story,15 though

his Garden works, such as Untitled (Table), also bring the two

stories together to reframe Oh’s legacy: instead of

considering Oh as someone who was largely forgotten, Untitled

(Table) shows Oh’s historical significance and how

he has continued to matter to people, as evidenced by the publications,

memorabilia, and other objects saved by members in his community that were

loaned for the show. Just as Jarman coaxed a thriving garden into existence

from a rugged landscape, so Lee’s Garden works help to

nurture Oh’s own growing legacy.16

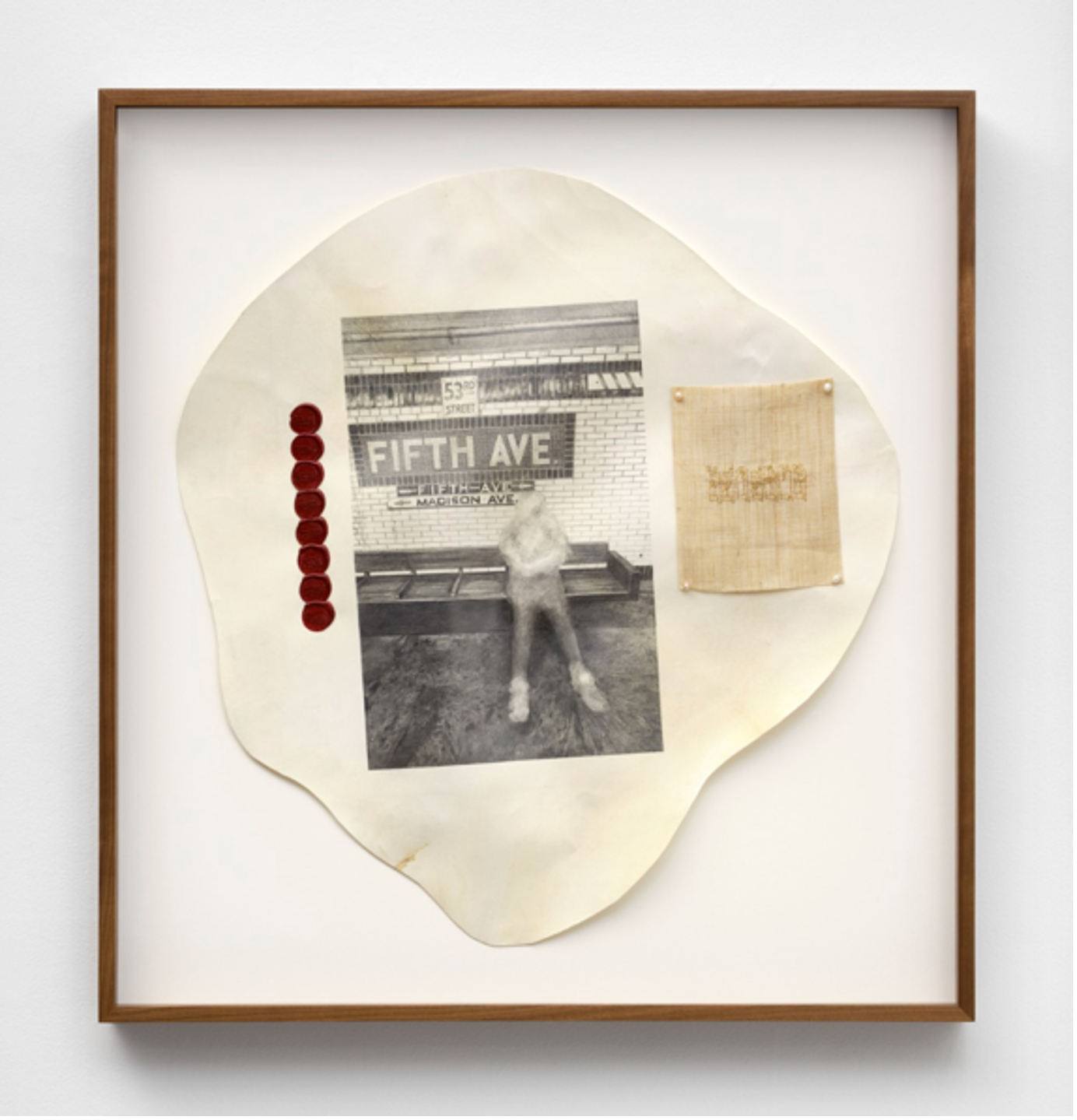

If Untitled

(Table) brings together objects to connect the legacies of two gay figures,

Lee’s Untitled 1, 2, and 3 series

(2021) from his exhibition Briefly Gorgeous (2021) at Gallery

Hyundai, in Seoul, collages together a more expansive and sprawling history of

queer desire and its manifold manifestations, one that spans the past century

to the present day. A heterogenous set of images and objects were assembled

onto the surfaces of three large wooden panels. They include a photograph of

Jarman’s Prospect Cottage; a still from Lee’s three-channel video Garden (2018); a graphite drawing of

Andy Warhol’s Hands with Flowers (1957),

tonally reversed; a photograph of the Transgender Memorial Garden in St. Louis,

Missouri; a graphite drawing of Jean Cocteau’s

illustration for Jean Genet’s Querelle de

Brest (1947); a photograph of a group of men standing in front of a large

banner that reads “WE’RE ASIANS

/ GAY & PROUD”; a graphite and watercolor drawing

of a work from the series For the Records (2013–ongoing) by the New York–based queer women

collective called fierce pussy; a graphite drawing of a photograph of James

Baldwin; feathers dating from the 1850s; pearls; stones; among many other

objects. Taken together, these elements represent the aesthetic discourse of

numerous generations of queer cultural producers, tragic consequences of trans-

and homophobic violence, as well as grassroots organizing of different groups

of queer activists. The insertion of Lee’s graphite

drawings of other artists’ works and small prints of

his own works into this series indicates the subtle integration of his own

presence within this cultural and historical microcosm. If conventionally we

are taught to separate “art history” from “world history” as represented by mainstream publications like Artspeak, Lee’s collage series Untitled 1, 2, and 3 tears down such

a construct by instantiating that art history is world history.

Video: Desire and Release

Desire, tinged with loss,

longing, and eroticism, courses throughout Lee’s most recent series The Heart of A Hand (2023), which is

based on the life and works of Singapore-born dancer and choreographer Goh Choo

San (1948–1987). Goh trained in ballet starting at

young age,17 and upon finishing university, he moved to dance

with the Dutch National Ballet. While in the Netherlands, he choreographed a

few ballets, which led to a position of resident choreographer and later

associate director of the Washington Ballet in Washington D.C. An outside

commission by Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theatre resulted in

the critically acclaimed ballet Configurations (1981), which led to

commissions from other renown dance companies around the world. Although Goh

was recognized for his artistic achievements during his lifetime, his sexuality

was not publicly mentioned. His longtime partner H. Robert Magee traveled

extensively with Goh and was introduced to Goh’s family

as his business manager, but their romantic partnership was never discussed. At

the height of his career, Goh died from an AIDS-related illness, as had Magee

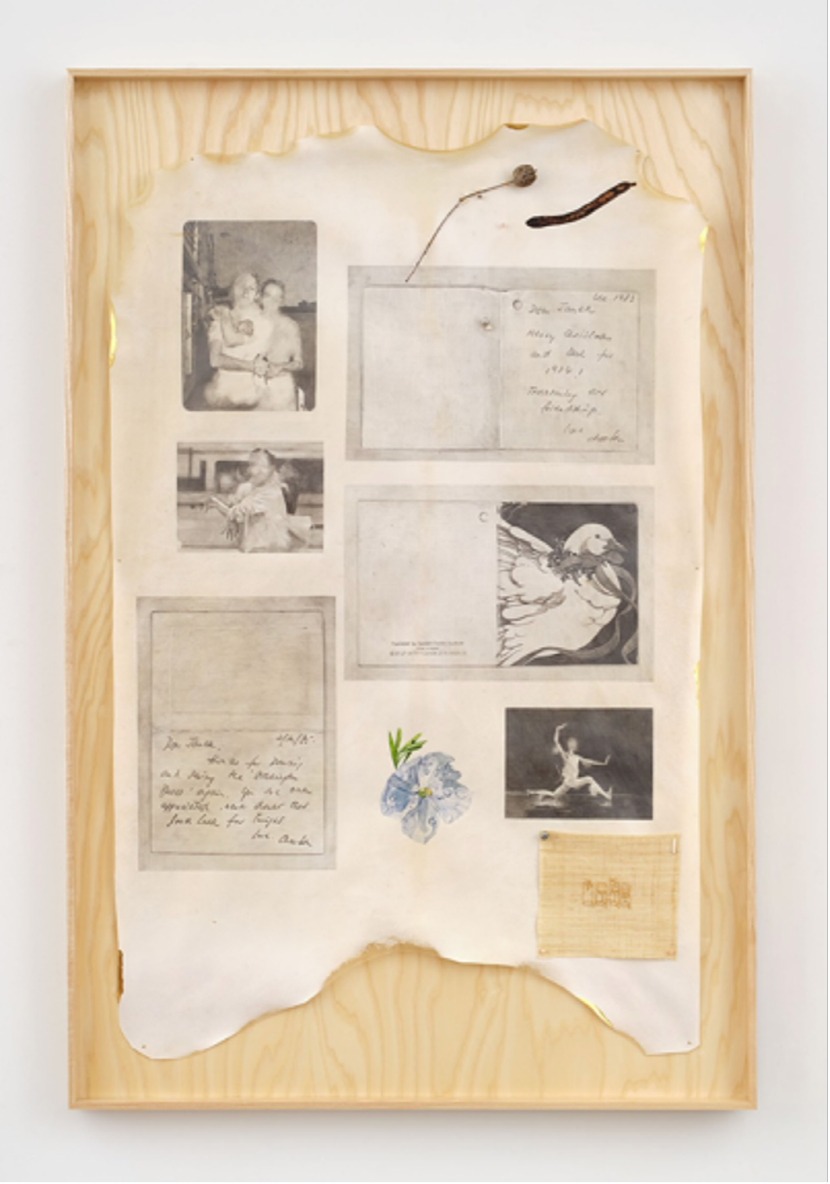

some months before. Lee’s mixed media on goatskin

parchment works for this series seem to reference the silence around this core

part of Goh’s identity through the blurring out of Goh

and other figures, including Magee, in his otherwise precise drawings of

archival photos. Coded representations of gay desire appear discreetly on the

parchment surfaces: pieces of oak gall from Elysian Park, a gay cruising site

in Los Angeles; pearls that evoke drops of semen; watercolor drawings of stones

from Prospect Cottage and gay cruising sites in Seoul and Singapore; fragments

from poems about desire by gay poets, including Xavier Villaurrutia (1903–1950), Donald Woods (1958–1992), and Samuel

Rodríguez (dates unknown),18 some translated into an American

Sign Language (ASL) font designed by the gay New York–based

artist Martin Wong (who also died of an AIDS-related illness in 1999).

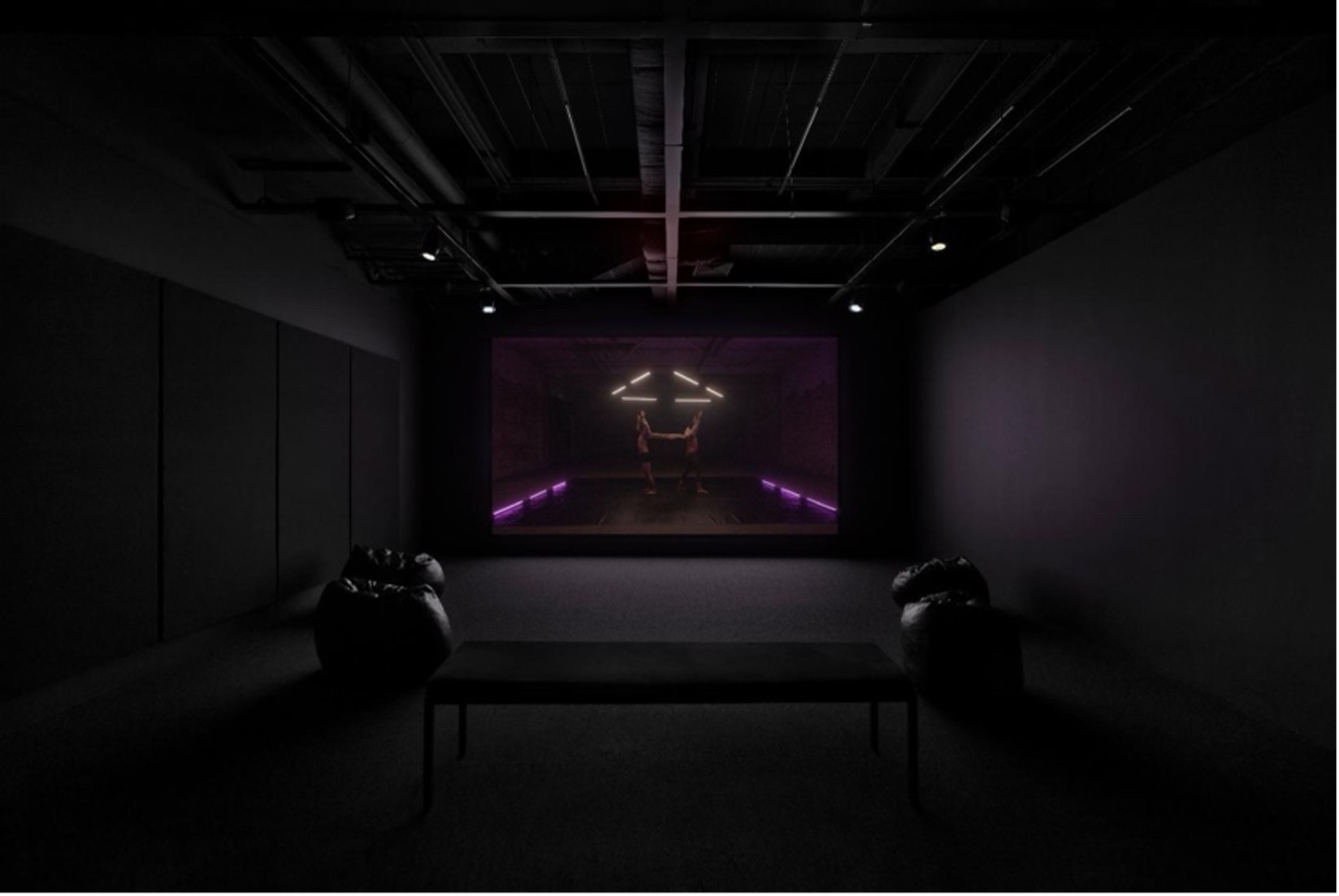

If desire only subtly appears in

Lee’s collaged, mixed media works for The Heart

of A Hand, it undeniably takes center stage in his video works for the series.

The video The Heart of A Hand was made in collaboration with members

in Lee’s queer community, including Brussels-based

non-binary dancer and choreographer Joshua Serafin, Los Angeles–based director of photography and film editor Nathan Mercury Kim,

and Seoul-based transgender composer KIRARA. The video begins with floating

hands in the Wong-designed ASL font forming lines from Villaurrutia’s poem “Nocturne”

(1938) that speak of a rush of sexual desire brought on by the darkness of

night. The rest of the video shows a masterful solo performance by Serafin, lit

in dramatic chiaroscuro. Serafin dances using an amalgamation of classical

ballet, modern dance, and dance moves that one might see at a night club. The

music pulses with the intensity of an EDM track. The source material for this

performance—Goh’s choreography

for Configurations, set to Samuel Barber’s Concerto for

Piano and Orchestra, Op. 38 (1962)—seems faraway.

Towards the middle of the performance, Serafin falls to the floor and a light

bulb drops down. The music slows down as their body twitches. Then, after a

burst of ecstatic dance, the final movement begins: Serafin’s body, now covered in gold paint and glitter, dances languidly and

sensuously. They slowly unspool a length of gold thread from their mouth. The

video ends with them looking straight into the camera with a smile, and then

laughing softly as they walk away. Through its imagery, sequence of movements,

and pulsating soundtrack, Lee’s The Heart of A Hand

video counters the prim classicism of ballet and the repression of Goh’s homosexuality with an aesthetic vision of struggle, seduction, and

release, such as the kind of liberation that one might feel while out dancing

in an underground club.

Whereas Lee’s The Heart of A Hand video centers on the narrative

journey of a single dancer, his Lazarus video (2023) focuses on the

intimacy created through interactions between two bodies. The source materials

for this work include Goh’s ballet Unknown

Territory (1986) and Brazilian artist José Leonilson (1957–1993)’s Lazaro (1993), a sculpture

consisting of two men’s dress shirts sewn together,

made shortly before the gay artist passed away from AIDS-related complications.

The video begins with floating hands in Wong’s ASL font

that spell out lines from Samuel Rodríguez’s poem “Your Denim Shirt” (1998). The poem’s narrator is speaking to a dead lover (“Mi

Amor”) who has died of a virus; he is throwing away his

lover’s belongings fearing that they might spread the

virus, but he is still in love. The music is pensive, paced at a moderate

tempo. Then we see a sequence of movements between two men, from close-up shots

of their hands touching to different configurations of their bodies rolling,

resting, and curling into each other on the floor in a large room. The room is

lit by florescent lights in a triangular shape, recalling the triangle in the

iconic “Silence=Death” poster

(1987) distributed to raise AIDS awareness. About halfway through, we see Lee’s remake of Leonilson’s Lazaro sculpture

in sambe on a hanger. The two men don the double-ended sambe shirt and the

lighting changes from cool to warm. The music turns more dramatic as the two

dance, moving away and towards each other repeatedly, in various configurations,

within the physical constraints set up by their shared shirt. At the end, the

two take off the shirt and set it respectfully on the ground as the lighting

turns cool again. One man places his arm around the shoulders of the other man

and together they walk away as the camera fades. The tone of Lazarus is

multivalent: while the work mourns loss, especially in connection to AIDS, it

also explores the emotional complexity and ambivalence of moving on from such

loss. Notably, Lazarus’s narrative is left

open-ended, with the suggestion that the Lazaro shirt can be

reactivated and thus re-signified, perhaps indefinitely.

Coda

Lee’s artistic practice illuminates networks of care, nurturing them in

the production of his series of works. His artworks help to raise the visibility

of queer figures and histories that have been overlooked or under-explored. He

operates from a place of abundance.19 Images, texts, and

objects collected from archives, libraries, collections, historically specific

locations, and more, are reproduced and reconfigured into new constellations.

Forms regenerate, taking on new lives in new contexts and assemblages. Communities

lead to new collaborations, as collaborations lead to new communities. His

works set things in motion.

Notes

The author would like to give

warm thanks to Kang Seung Lee, Sooyon Lee, Young Chung, and Uday Ram for their

generosity in exchanging thoughts about Lee’s works and related matters. She is also grateful to her mother Eun

Hee Moon for her translation help and insights into Lee’s works and their Korean cultural context.

1 Two books document this

project: the first edition of Lee’s Untitled (Artspeak?) was published for an exhibition at

the California Institute of the Arts; the second edition of Untitled

(Artspeak?) was published for an exhibition at Pitzer College Art

Galleries, Pitzer College, CA.

2 Lee used the 1997 version of

Artspeak. The latest version of Artspeak (2013) attempts to be more

international and inclusive, though its timeline still separates events into “world history” and “art

history.”

3 Tolentino’s Archive in Dirt was produced for the

exhibition Altered After (2019), curated by Conrad Ventur for Visual

AIDS, to which Lee also contributed an artwork. For more on this work, see

Tolentino’s catalog text in Altered

After (New York: Visual AIDS, 2019).

4 Lee writes about his reaction

to seeing Tolentino’s Archive

in Dirt (2019) in his and Jin Kwon’s essay “QueerArch” for Apexart. Kang Seung Lee and

Jin Kwon, “QueerArch,” Apexart,

https://apexart.org/QueerArch_E.php#secondPage.

5 Lee mentions the term “appropriation” in “Behind

the Beauty – An Interview with Kang Seung Lee.” The Artro, “Behind the Beauty – An Interview with Kang Seung Lee,” The

Artro, January 20, 2023,

https://www.theartro.kr/eng/features/features_view.asp?idx=5530&b_code=10&page=1&searchColumn=&searchKeyword=&b_ex2=.

6 Other drawings in Lee’s Absence without Leave series reference gay communities

in cities such as Seoul and Sydney, though the majority of the works relate to

New York.

7 Jung Joon Lee, “Drawing on repair: Kang Seung Lee and Ibanjiha’s transpacific queer of color critique,” Burlington

Contemporary, June 2023,

https://contemporary.burlington.org.uk/journal/journal/drawing-on-repair-kang-seung-lee-and-ibanjihas-transpacific-queer-of-colour-critique#fnref:6.

8 Kang Seung Lee, “Kang Seung Lee on Tseng Kwong Chi,” in

Denise Tsui, ed., Collected Writings by Artists on Artists, vol. 2 (Hong

Kong: CoBo Social, 2021), 96–103.

9 Even the Winter Scarecrow

Needs to Practice How to Live (Sungrim Publisher, 1993).

10 For an overview on the history

of sambe and how it has been made in South Korea, see Bu-ja Koh, “Sambe: Korean Hemp Fabrics,”

in Material Choices: Refashioning Bast and Leaf Fibers in Asia and the

Pacific, ed. Roy Hamilton and B. Lynne Milgram (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum

at UCLA, 2007), 79–91.

11 See Lee’s analysis of gold in relation to the theme “Madonna and Child” in his

exhibition and Child (2016) at Commonwealth and Council in Los

Angeles: https://kanglee.net/section/431813-and%20Child%20%282016%29.html.

12 For more on this exhibition,

see Jin Kwon’s essay in Garden:

Kang Seung Lee (Seoul: One and J. Gallery, 2018) and Doris Chon’s article “Generative Absence: Kang Seung

Lee’s Practice of Archival Resuscitation” in Kang Seung Lee (Seoul: Gallery Hyundai, 2023).

13 Lee’s Untitled (Joon-soo Oh’s letter) and

Untitled (Cover), which I discuss earlier in this essay, were originally

created for Garden.

14 On Jarman’s idea of how Prospect Cottage should be inherited through a lineage

of queer relations, see Leslie Dick, “Porous Bodies,” X-TRA, Summer 2020,

https://www.x-traonline.org/article/porous-bodies.

15 Park Han-sol, “Artist Lee Kang-seung’s mission to unearth

forgotten queer narratives,” The Korea Times,

November 9, 2023, https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2023/11/398_362871.html.

16 To get a sense of how rugged

Dungeness is, see Howard Sooley, “Derek Jarman’s Hideaway,” The Guardian, February 17, 2008,

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2008/feb/17/gardens.

17 The youngest of nine children,

Goh had three siblings—Goh Soo Nee,

Goh Choo Chiat, and Goh Soo Khim—who also trained in

ballet and became prominent figures in the field.

18 Samuel Rodríguez’s poem “Your Denim Shirt” appears in the introduction of Robb Hernández’s book Archiving an Epidemic: Art, AIDS, and the Queer Chicanx

Avant-Garde (New York: New York University Press, 2019). This is where Lee

found the poem but no other information about the poem or the poet seems to be

publicly available.

19 Joan Kee made this perceptive

comment in her Zoom conversation with Lee on the occasion of his

exhibition Permanent Visitor (2021) at Commonwealth and Council:

https://commonwealthandcouncil.com/together. This also resonates with the

principles of “The Revolution” as conceptualized by artist Jennifer Moon, a friend of Lee who has

collaborated with him on multiple projects. The first principle of “The Revolution” is “1)

Always operate from a place of abundance.” More on “The Revolution” can be found here: .

Jennifer Moon, “About the Revolution,” The Revolution, http://www.therevolution.jmoon.net/About/